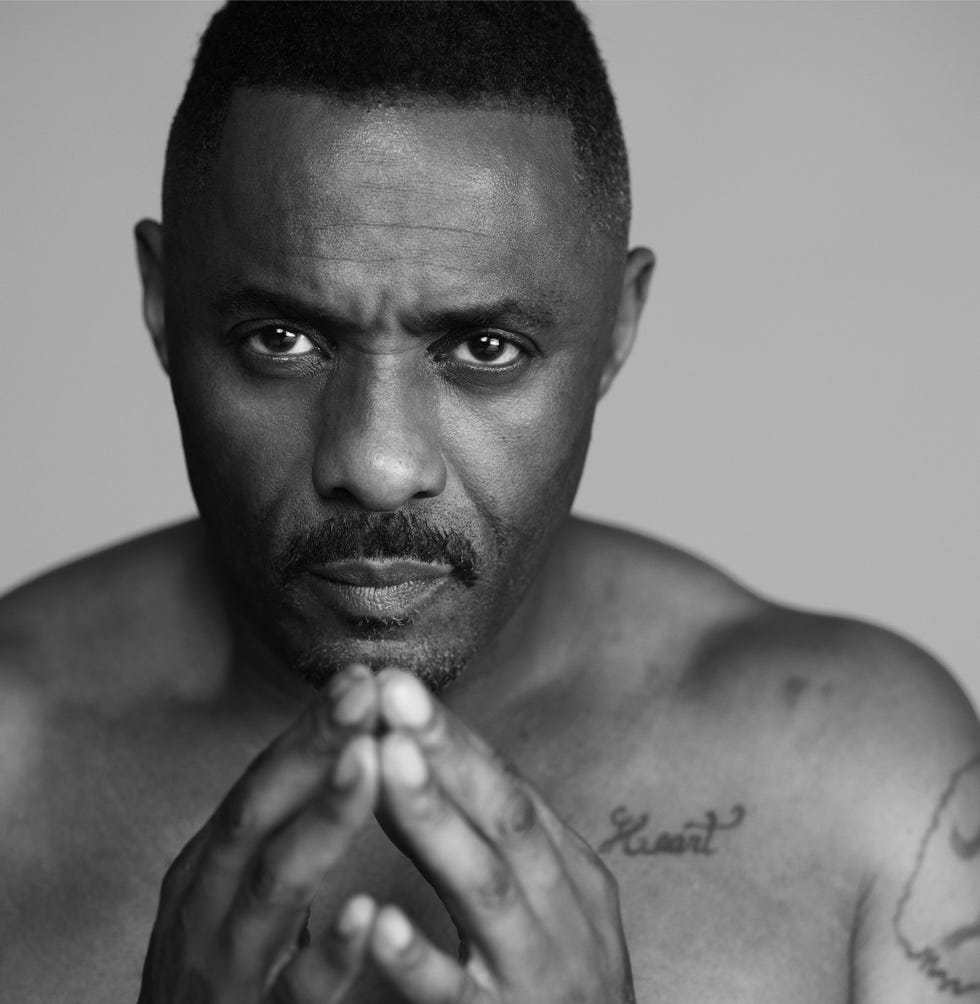

The first thing that strikes you, on being introduced to Idris Elba, is the scale of him. He’s enormous. He’s monumental. He’s widescreen. He’s epic. In 2017, Elba made a movie with Kate Winslet called The Mountain Between Us. He didn’t play the mountain, but I’d like to know why not; a fortune could have been saved on locations. Last year, Elba made a thriller called Beast, in which he punches a lion in the face. This seemed somewhat implausible to me until I encountered Elba in the flesh. Now I marvel at the lion’s ability to absorb the blow. Poor kitty.

Perhaps you’re thinking that you don’t have to meet Elba in person to appreciate his powerful physical effect. It has been clear for 20 years now, since he first broke through as Stringer Bell, the thinking person’s drug dealer, in The Wire, not only that here is a man who commands attention, an actor with rare charisma, a star — but that here is a big star. Huge. You get it.

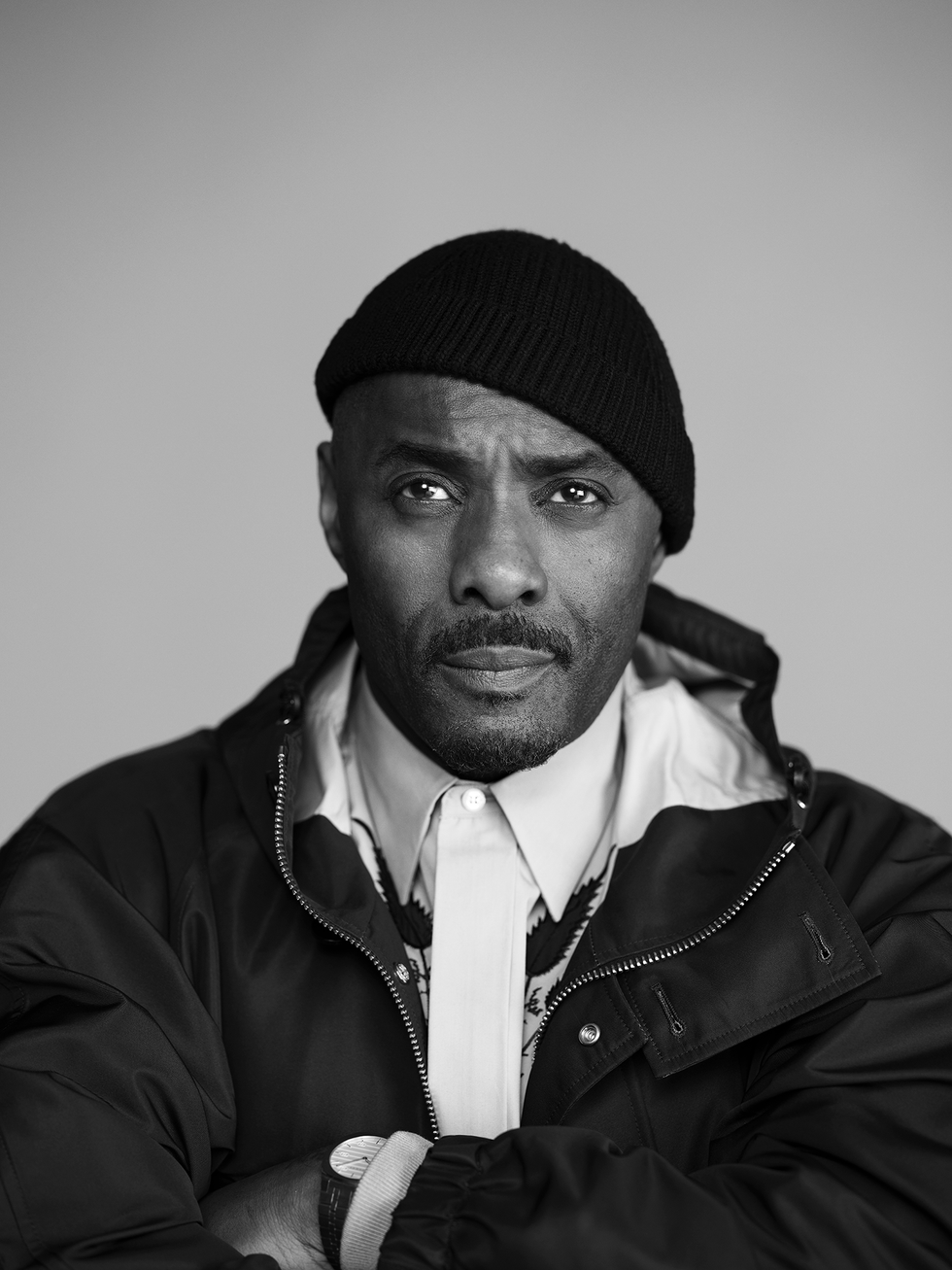

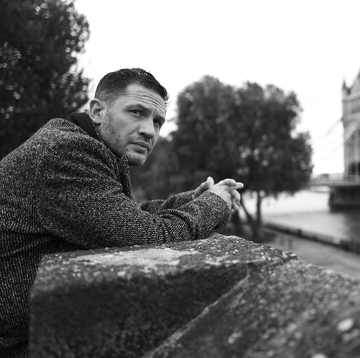

Sorry, but no. You don’t get it. In fact, I had met Elba before, in passing, on a couple of occasions over the years, and still I was taken aback when I walked into the famous Abbey Road Studios, in London, on a Tuesday lunchtime last November, and clocked him through a window sitting at a tiny desk (on closer inspection it turned out to be normal-sized), tapping on a miniature keyboard (actually, standard-issue MacBook). As he corkscrewed upwards from his doll’s-house chair (regulation office furniture), I stepped back for a moment to take him in. He was wearing a faded black tracksuit that could do double-duty as a dance tent come festival season and unlaced Dr Martens boots. On his head was perched a child’s beanie. He beamed and disappeared my own, perfectly reasonably proportioned hand inside his enormous fist.

The only child of immigrants to the UK — his father was 33 when he arrived from his native Sierra Leone; his mother, born in Ghana, was 26 — Idris Elba is one of a handful of British actors who can justly claim to be Hollywood leading men. His story is well known: the boy from the east-London council estate who, in the 1990s, followed his dream of being an actor to New York, made his name with that extraordinarily controlled and seductive performance in what remains one of the finest TV dramas ever made, and went on to big-screen success and cultural ubiquity — as an actor, director, producer, DJ, musician, rapper, entrepreneur, fashion designer, philanthropist, dare-devil, podcaster, heart-throb, and I’m sure I’ve missed a few. A father of three, he has been married since 2019 to Sabrina, a Canadian model and actor of Somali descent. They live in west London.

Elba’s genre-hopping career suggests wide-ranging interests and a restless nature, as well as a Stakhanovite work ethic. Highlights include his Nelson Mandela in Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom (2013) and the mesmeric Commandant in the terrific Beasts of No Nation (2015). The baddie in Star Trek Beyond (2016). The ship’s captain in Ridley Scott’s Prometheus (2012). The irascible Bloodsport in the outrageous The Suicide Squad (2021). He was Heimdall, a Norse god, in Thor (2011), a role he has reprised in no fewer than five further Marvel movies. He has spread his honeyed tones over a menagerie of animated characters. In 2016 alone, he was a buffalo in Zootopia, Shere Khan the tiger in The Jungle Book, and a sea lion in Finding Dory. And, yes, he was Macavity in Cats (2019), one of a vanishingly small group of actors to emerge from that film with their dignity, mysteriously, intact. Count them on one paw.

Last year offered his career in capsule: an echidna with attitude in Sonic the Hedgehog 2; the lion-punching dad-in-peril in Beast; a genie in George Miller’s arthouse fantasy Three Thousand Years of Longing, with Tilda Swinton; and Heimdall again in Thor: Love and Thunder.

The reason for our interview is to promote a new movie: Luther: The Fallen Sun, a feature-length expansion of his hit BBC cop show, which will appear in cinemas later this month and on Netflix in March.

The brainchild of British novelist Neil Cross, Luther is a lurid crime drama set in contemporary east London. Over five series since 2010, it has followed the considerable tribulations of the grizzled, melancholic DCI John Luther, an archetypal fictional detective: a brilliant loner consumed by the job, with a disastrous personal life to show for it, as well as the most traumatised screen overcoat since Columbo hung up his mac.

Haunted by the death of his ex-wife and, most entertainingly (for the viewer), the legacy of his toxic entanglement with Ruth Wilson’s genius psychopath Alice Morgan, Luther appears before us in shades of grey, like London itself, with the occasional shock of red to puncture the gloom: his tie, a London bus, a bloodied corpse.

Elba has been exhaustively profiled, not least in this magazine — this issue marks his fourth appearance on the cover of British Esquire — so we agreed before we met, on a Zoom call last October, that we would not limit ourselves to the traditional stagger through the CV. Something more freeform was appealing to him.

Elba recently turned 50. There are those who dismiss milestones like that. Age ain’t nothing but a number. Others panic. So little time, so much still to do. Perhaps most find themselves somewhere in between — reflecting, ruefully or otherwise, on triumphs and disasters, inspecting themselves for signs of wear and tear, taking stock.

Elba flip-flops slightly on his attitude to entering his sixth decade. On the video call, he’d mentioned that he’d had cause to meditate on the passing of time, the different phases of his life to date, and lessons he’d learnt along the way. On another occasion, in person, he brushed it off: “Every day is my birthday. I didn’t make a big deal out of it.”

“Physically I feel fine,” he told me. “Things move slower. You definitely feel those aches and bumps. But then, I always have. I live an extreme lifestyle, I guess.”

The conversations for this article took place over three days in November. They began in Studio 3 at Abbey Road, where I watched Elba and his collaborators in a new musical project, the Black Specs, working on material that may or may not become an album. Certainly, this was no dilettantish noodling. The players are accomplished; the influential A&R Lincoln Elias, a name to whisper with wonder in British music circles, was on hand to dispense wisdom and good vibes; and Elba appeared to be in his element.

“It’s not a hobby,” he said, of the Black Specs, during a smoke break on the roof of the building. And, yes, we did pause for a moment of reverential appreciation of Those Who Have Smoked Here Before.

A few days later, Elba and I sat alone in another recording studio, in Shepherd’s Bush, cosy but less glamorous. The following week, we talked again while he was having his hair and grooming done for the photos on these pages.

The song that he and the Black Specs were working on at Abbey Road was called “Future”, a hip-shaker recognisably in the tradition of British neo-soul, a genre over which Lincoln Elias can claim much influence. I began by asking Elba about the past. He wasn’t sure that was the best place to start. “Life offers up a new day every day,” he said. “Let’s not get bogged down with yesterday.” I said we’d play it by ear, see where the conversation took us.

Throughout our time together, he was warm, open, thoughtful. Also, big.

1. Never a cool kid

I’m the same person I always was. Only child. And I’m still an only child, even though I’ve got a lot more people around me. Introspection has always been a part of me, since I was conscious. That introspection is still very alive now. And I feel very connected to that young guy, who was very ambitious in his thoughts. Curious, always curious.

Homosapiens: we’ve got hunters and gatherers, and we’ve got watchmen. Watchmen are a type. What they are really good at is sitting still, and observing. An only child is a bit like that. Your self-reflection comes deeply from within. That is a type of person. I’m that type. Not all only children are like me, but I imagine there are similarities. For me, it just means you are an individual. You are one of one. That’s what it’s like for me. That’s what I think about.

I’ve never really had envy. When I was a kid, I remember thinking: “Why haven’t I got brothers and sisters? It looks so much fun. Because they go home and they’re in the same bedroom and they’re talking all night, and mum comes in, ‘Shut up you lot!’” For me, it was none of that. I was conscious of that. But then it becomes, “Wow. I’ve got solitude they don’t have.”

Sometimes, when you’re in the playground, kicking a ball against the wall by yourself, or with one other person, and you’re getting better, and you’re doing skills, the next thing you know, other people are doing it and trying to be around you. You’ve created something. That’s interesting to me.

What did I get from my dad? People pleaser. My inquisitive nature. If someone knows something, I want to understand it. My dad was like that. It’s funny — I didn’t see him sitting with books. We didn’t have a library at home. But he would quote books. He just seemed to have a universe of facts, and a perspective on everything. I’ve always admired that.

My dad was one of 11. And he was a cool guy. The guy who had all the friends. The guy who everyone wanted to be around. I was never a cool kid. I was always trying to emulate the cool kids, but I couldn’t do it. There were kids who were good at football, cool clothes, cracking jokes, all the attention on them. Playtime comes, I would not be in that group. I would try to fit in but oftentimes that would end in failure. Still happens to me today.

He worked at Ford’s [the car plant at Dagenham] for a long time. He went from employee to shop steward, worked his way up the union. That takes guts, because you’re challenging the hand that feeds. And he was vocal. Me, I want to see the world a bit more. My dad, he didn’t want to go on holiday: “I’m alright right here.” I’m a little bit more ambitious.

2. Another culture

Although I was born in England, the first culture I experienced was Sierra Leonean. The food, the environment, the music, the clothes, the attitude to the weather. All my experiences were West African first, then UK culture. I love being English, I love the culture here, I grew up here, I became a man in England, I’m very attached to it. But at the same time, I’ve also got another culture, which is African, Sierra Leonean specifically. I’m really thankful for it.

I come from a tribe — the Temne tribe. I understand what that means, having been to Sierra Leone a few times: the difference between the Temne tribe, the Mende tribe and the Creole tribe. I get it. Characteristically, the Temne are a forthright, book-smart, take-no-prisoners type of people. A bit like how you’d consider a Scotsman — proud, strong, forthright — where the English might be diplomatic, stiff upper lip.

It’s very Sierra Leonean to be polite and courteous. It’s given me principles, guidelines, to some degree, manners. Work hard — that definitely comes from my West African roots. I’m not flashy. There are cultures where it’s good to show off, to show your wealth, what you own, where in the pecking order you come. In Sierra Leone? Don’t show off. Be humble. You can be the biggest star in the world, but you brush your teeth like everyone else. You take a poo like everyone else. Even though you’ve got a talent and everyone’s celebrating it, don’t live on that. Don’t be a dickhead.

I work with actors who really believe their own press. That’s a sadness.

My mum, she was born in Ghana. She’s from Accra, the Ga tribe. She moved when she was 12 to Sierra Leone, but she was quite attached to her Ghanaian roots. Again, I’ve been to Ghana many times, worked there, understood how my tribe offers me perspective on who I am. I think the Ga are quite sensitive people, sensitive to possible slights. Cautious. I can be like that.

Energies are a big thing with me. If someone comes with a negative energy, I can sense it. If I don’t sense it immediately, I’ll get to it. There’s also a relaxed aspect, pragmatic. I can be like that. If it doesn’t happen, it’s OK. Not gonna stress about it. Next time…

When you become famous, it’s not just you who gets affected. My mum, she doesn’t like the process, this process. “People are so nosy! Yeah, I used to be a Avon lady: so what?” That’s been a tough one to deal with sometimes because I like to speak openly about my family. And then my cousin will be like, “Oh, man! What did you tell that story for?”

By the way, my mum is a very strong woman.

I had chronic asthma as a kid, and eczema. To some degree I was a poorly kid. I was in and out of hospitals. My mum was worried, often. So I know her protectiveness, and her strictness, was about that. I read somewhere recently about the effects of a strict parent, and how that can create alternative ways of thinking as an adult. It’s like the devil on your shoulder is much bigger than the angel. Because they’re going, “Should you be doing that? You shouldn’t be doing that!” And then it’s human nature to be more attracted to going to places that you shouldn’t go. I’m no psychiatrist, but you’ll find that some of the deviant personalities, when you trace that back, it’ll often be that the parents were strict. I recognise that, 100 per cent.

3. Just skin

Holly Street Estate. Ninth floor. It has changed now. Been knocked down to a large degree. But it’s still, in essence, exactly what it was and, geographically, exactly where it was. I love going back. I look up in the sky. These skyscrapers were my first understanding of scale. Of who I am, how I fit. Huge, 19 floors. So when I go back, and I look up, I get to see this view and understand my scale differently now. Fucking fascinating.

People say you come from a tough neighbourhood. That’s not a tough neighbourhood. If you’ve come from that place, lived there all your life, that’s just home. It’s a tough neighbourhood compared to where you come from.

My stance against knife crime is because I know that feeling. I was there as a teenager. I was like, “If anyone picks on me, man, I’m just gonna juk ’em up.” That power surge, which is a deviant strain: to feel powerful because you have this tool in your backpack, concealed. I was there. There are kids out there right now, seemingly normal, not necessarily in gangs, that are carrying sharps, carrying knives, just in case. I didn’t go there, but I thought about it. I know most people can’t understand that. I understand it.

I enjoyed my childhood. I liked my best friends. I loved riding my bike, being by myself, finding new roads, pedalling faster, slowing down, just the skill of balance. I loved that.

Canning Town was a different experience altogether. We lived in a house, which was a step up for my parents. Now we’re on the property ladder. But I went from this community where you get in the lift and you see your neighbours every day to a terraced street where the sense of community was lost for me.

I didn’t like Canning Town, didn’t like it at all. I was like, “When can we go home to Hackney? Go Ridley Road Market.” It was a right-wing, white, working-class community. There weren’t that many Black people, weren’t that many Asians. In my school there was a lot of Black and brown, but the neighbourhood, not so much.

I’m always curious why this is fascinating to people. It’s a question I get asked a lot. I don’t go to my Black friends, in conversation, and ask them to tell me about racism. Have I ever faced racism? Yeah.

I’m not any more Black because I’m in a white area, or more Black because I’m in a Black area. I’m Black. And that skin stays with me no matter where I go, every day, through Black areas with white people in it, or white areas with Black people in it. I’m the same Black.

If we spent half the time not talking about the differences but the similarities between us, the entire planet would have a shift in the way we deal with each other. As humans, we are obsessed with race. And that obsession can really hinder people’s aspirations, hinder people’s growth. Racism should be a topic for discussion, sure. Racism is very real. But from my perspective, it’s only as powerful as you allow it to be. I stopped describing myself as a Black actor when I realised it put me in a box. We’ve got to grow. We’ve got to. Our skin is no more than that: it’s just skin. Rant over.

Of course, I’m a member of the Black community. You say a prominent one. But when I go to America, I’m a prominent member of the British community. “Oh, UK’s in the house!”

I accept that it is part of my journey to be aware that, in many cases, I might be the first to look like me to do a certain thing. And that’s good, to leave as part of my legacy. So that other people, Black kids, but also white kids growing up in the circumstances I grew up in, are able to see there was a kid who came from Canning Town who ended up doing what I do. It can be done.

I didn’t become an actor because I didn’t see Black people doing it and I wanted to change that. I did it because I thought that’s a great profession and I could do a good job at it. As you get up the ladder, you get asked what it’s like to be the first Black to do this or that. Well, it’s the same as it would be if I were white. It’s the first time for me. I don’t want to be the first Black. I’m the first Idris.

4. The scale of it

New York was a pilgrimage. America was this shiny dream-state. Look at the scale of it! Look at the music, look at the culture! Look at the TV, film, magazines! I was 17, 18. You just felt the opportunities. You could start off with a dollar, in New York, and rise. That was real. That’s why I went. Is that the same America we’re looking at today? Perhaps not. Things have changed. But I’m looking at it through 50-year-old eyes now.

The plan was to work my way into the consciousness of directors and casting directors, and show what I’ve got to offer as an actor. I was doing it in England. I had a decent level of success. I wanted to go to America and see if I could do the same. Didn’t want to change the world. More than anything, just wanted to live. I had seen east London. Seen it, worked it, loved it. Wanted to live somewhere else, see something else.

I often think about going to live in Africa. It’s the same feeling I had back then about going to live in America. Something different, a challenge. I want to go where there is ambition, progression, optimism. Change.

America gave me technical understanding of my craft. It was an enhancement. I learnt a lot. American actors have always been great. The works of Shakespeare live in a world of wonderment, poetry, fairytale, the language of beauty and eloquence. The performer uses a skillset that amplifies that. There is an air and a grace to it that a good English actor has to understand. In America, in an Arthur Miller play, you might get a guy who’s just a guy. Guy from Pennsylvania, guy from New York. Just a guy. A human. American actors had this connection with real life. The accent and the cadence of the words in America allows for a really interesting flow of thoughts.

In England, I did a TV thing for kids, and then a soap opera. But unless I was doing Shakespeare, or one of these highbrow things that are outside of my actual culture, I wasn’t going to elevate in this country as an actor. In America, it felt like the sky was the limit. You didn’t have to do Shakespeare to be a good actor. I found it really freeing.

In fact, I did Shakespeare in America, off-Broadway. Troilus and Cressida. I played Achilles. Sir Peter Hall directed it. Loved it.

Stringer Bell, he was a small character in the pilot, few lines here and there. I identified with him a lot. He was an underdog, right? I was an underdog. And the feeling that I’m not the guy, I’m the guy next to the guy. Or, I’m not the guy yet, but I could be the guy.

I always had a fear that I would end up like Stringer Bell. I always felt like, damn, this guy was going places, he was fucking smart, everyone liked him, and he got moped out. I always feel like, that could be me. I could get run over, I could get stabbed, I could get shot. I could get an illness. Nothing’s permanent.

I didn’t think it was real. I thought it must be a joke. They can’t be asking me to play Mandela. Come on, that’s ridiculous. He’s one of the most iconic human beings ever. I’m this actor, east Londoner, and you’re asking me to play him? I felt like, if I got this wrong, my career would be over.

If Denzel played him, it would be, OK, this is Denzel’s Mandela. Because Denzel is a man of stature. Like Denzel playing Othello. I didn’t think I quite qualified. Idris Elba’s Mandela? But I was dedicated to making sure I gave it a good shot.

Luther, he’s probably the character that’s most like me, in real life. He has so much conviction. He doesn’t try to overcomplicate things. He gets to the point. I love the writing. It’s fun to play. Hopefully this is a series of movies expanding the John Luther stories, bigger canvas, more bandwidth to find out who he is, understand him a bit more.

I know what you’re about to ask and I think it would be amazing if you didn’t ask it. People will be like, Whaaaat? They didn’t even mention it!

5. A song called “Ego”

In the circles of being an actor, being in the public eye, there are cool groups, people who have got a lot more attention than me. Better-looking, better actors, whatever. I’m still not part of a group. I do my own thing. Bit of a loner, I guess. Or maybe not a loner, but small groups. One other person, maybe two.

Imposter syndrome? Yes, definitely, all the time. And that can fuck with your insecurities. It can fuck with your personality. And where you should speak up, you don’t. Because you feel you shouldn’t be in the room.

Guess what? I can hold the microphone. I can punch hard. I can kick a ball.

The magic of cinema is that people are watching a story in a very controlled environment, where their eyes are focused on the screen, and they get absorbed by that, and by those people. But those people aren’t real. That guy you can see, he’s not really a detective.

My public persona is exactly that — it’s a public persona.

In my personal life, there are things that I’m not great at. Not successful at. That I don’t have a grasp of in a way I’d like to. If I like being by myself all the time, what happens when I open the door and loads of people come in? That is a challenge, and that is something I am not very good at. I prefer my own company. I function better on my own. I’m more at ease.

I’m catastrophe-ready. In the film industry, you always think: worst-case scenario, what would happen if there were an explosion? What would I do? What would happen if this guy walks in and he’s kicking off? I’d have to fucking knock him out. They’re kind of dark thoughts. But depending on how you decipher what I’m saying, I think there might be readers who will go, “Yeah, man. I kind of relate.”

My job encourages me to make sure I take my vitamins. So my skin looks good, my eyes are bright, my body is in shape. And that’s a gift, but it’s also a stress. If I just wanna crack open a six-pack of Red Stripe, I’ve got to think about what that might do to my camera persona. It’s part of the game.

This interview is interesting because you’re here in my most deeply personal environment. Even though music is for putting out, I’ve made so much music, rented so many studios and never put anything out. The consciousness within this space, the nurturing, the therapy I get from it, is what is meaningful. Not “Press Play” on an Apple list. When I’m in this space, I’m self-reflecting.

We wrote a song called “Ego”, and honestly it is probably the most “me” I can be outside of my own skin. The chords, the instruments, the progression is a personification of me in that moment. In actuality, I’m not singing, I’m talking. I didn’t write any of the lyrics down — it’s a stream of consciousness. And it’s a very vulnerable moment. And as far as I’m concerned, that song can never, ever come out.

6. Pure as could be

My son and I did some homework the other day. He had to mummify an orange. Me and my wife and my son, we sat and we did this. Nice family moment. We sat down, we did some research, we looked at the mummification process. We said, what do they want? They just want a picture of an orange if it were a mummy. Right. So we did that. We stripped it down and we thought about it, and we used toilet paper. But the real process of that was seeing my son express his inner self, pure as could be. And we had this orange. And we almost didn’t want to let it go. We were like, we should do another one, because this one is so special. If you put it out there, it’s gonna be judged. People are going to have something to say about it. It becomes something else.

My children love me and maybe that’s helped me love myself a bit more.

Boys and girls are different but you aren’t as a parent. Dad advice is dad advice. I’m not going to give my daughter different advice from my son because she’s a girl.

I kind of see myself as like a quantum-physics computer. My brain has the power of computers unknown to us yet. Computers can do multiple things at the same time, and so can our brains. All the things I do, it’s the same source, different applications.

I made an album called Mi Mandela that I’m pretty proud of. A little bit of a love letter to my old man, and to Nelson Mandela at the same time. Proud of Yardie, the film I directed. I did this music video for a guy called Rehab. Pretty proud of that. Did a video for Mumford & Sons. Proud of that, too.

I’ve got a creative appetite. But I’m good at staying still, too. I can kotch. I’m the kotch king.

The assumption is that if you make a lot of money, you can stop working. I don’t work for money. I do have mouths to feed, businesses to run, taxes to pay. But I do it out of love. I do it because I want to. I’m interested in taking my brain to a place where it hasn’t been before.

I believe that we can put all this importance on what Idris said, or what this other actor said, or what this politician said, but the truth is, I’m going to die. And when I die, along with me goes my spirit. The only thing that matters is what is left. But dying isn’t the end of the world for me. Everyone has to do it.

You can either live a nothing life, or you can live the fucking craziest life, and enjoy it. Trust me, in 3,000 years, no one’ll even remember I existed. That’s my theory. Nothing matters.

7. Psssshhhht!

Some of the stuff I’ve done is powerful, and some of the stuff that isn’t powerful is still powerful to me.

I don’t watch my shows unless I have to. I’m not interested. I was there. I gave. If I go to a premiere for a show, the likelihood is I’ll position myself close to an exit and as soon as I can… psssshhhht!

In interviews I’m always cautious what to say. More and more. Because things outside of this room, coming straight from your head and being edited and sub-edited and then on to the paper, the sense changes from what it was in the room. If I read anything, I read what I actually said. In quotation marks. All that stuff: “We sat in a dusty room, Idris was a little tired…” To me, that’s not it.

What is the point of being scared? What do I get from that? Protection? I’ve got logic for that. Even my worst nightmares: being buried alive, being mangled in a car crash, I don’t fear those things happening. What’s the point?

I say to my son, what are you afraid of? He says, the dark. I say, why are you afraid of the dark? He says, the monsters. I say, have you ever seen a monster in the dark? No. What is it then? It’s my imagination. Are you afraid of your own imagination? In the dark I am. Yeah, but you don’t have to think about those things. This is a real conversation. I don’t want to say to him, don’t be scared of stuff. But fear will cripple a man from doing anything. Have you ever wanted to do something and you just haven’t done it because of fear? Is that fair to yourself? Just do it! It’s OK to fail.

I’ve learnt a lot. I’m better equipped to deal with things I’m going through. That comes from experience. I’ve learnt to exercise patience. That’s a gift. I wasn’t so good at that in the past. I’m more organised, more conscious of being neat, presentable. I work in the presentation business. I share my world.

When I was younger, I hated my smile. I didn’t like smiling. I didn’t think it made me look cool. I thought it made me look goofy. And then I realised that when I smile, people smile with me. Without a doubt. It’s an odd phenomenon.

Yeah, I feel older. I feel my age. A ripe old age. But 50 is a beginning for me. ○

‘Luther: The Fallen Sun’ will be released in cinemas on 24 February and on Netflix on 10 March