Over a century since the Spanish Flu and the first race riots between Black immigrants and the white working class, it almost feels as though everything has been on repeat. Observing the past hundred years through the lens of the policing of Black people in music spaces, it’s clear that these interactions have always been representative of the wider treatment and attitudes that the state and Britain as an empire has had towards those deemed ‘other’.

The trajectory of Black music in Britain has been shaped by experience and response to the environment. The history of the censorship and criminalisation of Black music has been well-documented in the US but less so here; there are patches of stories told, but seldom are they woven together to create a thread that details how it often feels as though history is on loop.

The idea that life has seemingly improved for Black people in Britain is predicated on a fallacy that 'mildly increasing tolerance' is the same thing as 'acceptance'. The Tory government of the past decade has only made that more apparent, particularly when it pertains to the censorship of Black music. Illegal raves, and by extension a physical underground scene, will likely emerge in the immediate to foreseeable future. For now, the over-policing of areas with high numbers of Black and ethnic minority groups has already seen a disproportionate rate of arrests and prosecutions for minor offences, even more so since BLM-aligned protests began in early June.

There were early predictions that the Covid-19 pandemic would lead to a resurgence of illegal raves, and reports from earlier in the summer of police being called to street parties in Brixton, Tottenham and Harlesden have peculiar echoes. In the months since the Coronavirus Act was put into effect on 25 March, the police have been shown to be abusing the powers it grants them. While what’s been communicated to the public and police doesn’t match, the real concern is around the section that gives them extra powers to order groups to disperse. A group of young people could be walking home from school, or some twenty-somethings could be having a house party; under the Coronavirus Act, the police can and have used this to criminalise Black people. In regards to music specifically, in the current climate, the powers could be used to order the shooting of a music video to cease even despite lockdown being eased.

In order to fully understand the ways in which Black people are affected by the state and its agents (police, education, housing etc), it’s important to retrace our steps back to 1919, a year after the Spanish Flu and the last pandemic that swept Europe. The Race Riots of 1919 led to a rise in tensions between Black people and the police, who were often ordered to end the labour strikes that had sparked the unrest across the country. Right-wing sentiment towards Black immigrants in regards to them being responsible for labour shortages can be traced back to this period, when Black workers who arrived after the end of the first world war would seek employment despite strikes over pay. As Dave Haslam writes in Life After Dark, in the 1910s, when jazz first arrived in Britain via Black American soldiers, the music was considered by society more widely to be "morally bad". Events were routinely shut down – albeit often unsuccessfully – and although Black people hadn’t been residing in Britain in the numbers we see today, the sentiment was that, as a populace, they must be somehow deviant and unruly.

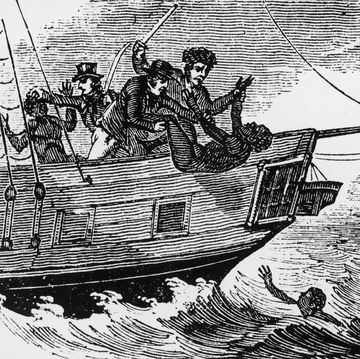

Pay disparities meant that Black workers often had no choice but to break the strike lines, which also led to tensions with white workers and other migrant groups. Rioting broke out in Britain’s major port cities where many war veterans found work, but it was in these regions such as Bristol, Cardiff, Liverpool, Glasgow and London where jazz emerged at the same time. As the music grew in popularity, attacks on Black immigrants rose. Band member with the Southern Syncopated Orchestra, a pioneering Black jazz group that toured the UK between 1919 and 1921, often had to travel between gigs under police escort. Black people without a public profile got even rougher treatment, targeted by the police even as white working class mobs attacked them and burned down their homes.

The links between Black music, Black life and policing can’t be separated and the importance of stating genres such as garage, jungle, jazz and grime as Black working class-led genres is imperative when looking back at the history of Britain and white working class sentiment towards Black people. The police have always played a central role in this dynamic, as their primary function has always been to protect property and white Britons from those considered deviant. While this has never typically included the white working class, the police have often ignored violence towards Black people. The lives of Black people in Britain have historically always been under surveillance and through music, expression has always been censored in a myriad of ways, in keeping with the evolution of policing.

Since The Windrush Generation, and those who arrived from Africa, music became an outlet for anti-sus law (the precusor of stop and search) and police thought and commentary in keeping with the Black resistance movements that arose in the Fifties. While reggae and jazz were the primary targets of media and state censorship, other genres such as ska and punk were also born out of anti-establishment sentiment. In Eighties, and Thatcher's Britain, there are even echoes of the late 1910s; many of these scenes exploded in the major port and industrial towns where youth unemployment figures were at their highest, particularly among Black people. There are countless stories of clashes with police and right-wing mobs in music spaces, many of which have been depicted in cultural media today.

Reggae musician Dennis Bovell was falsely imprisoned in 1974 following a disturbance at Carib Club on Cricklewood Broadway. In an interview with The Quietus, Bovell retells the story of when he was deejay on the night and was accused of stirring trouble between police and the audience, where he was later charged due to ‘sus laws’ granted to police under the Vagrancy Act of 1824 to arrest people on suspicion of being about to commit a crime in a public place.

“Well, police wanna pull me over in my car / Check my licence and plates / Then ask me how much it cost / Get the fuck out my face,” Kano raps on New Banger, released in 2016.

The 1980 film Babylon, starring Brinsley Ford, was inspired by Bovell’s story, and the pattern of police surveilling establishments where Black people congregate in public, and later criminalising them, has only been repeated in the years since, with the police becoming increasingly more clandestine with their tactics. Historically, young Black people have always been the target of heavy-handed policing and punitive measures. Combined with the belief that the public gathering of young Black people is seen as non-compliant and deviant by simply being, it’s not just in music spaces where they are seen as potential suspects but often, it begins in schools through school exclusions.

More recently, there’s been a pattern of drill MCs who have been previously excluded from school, later finding themselves caught up in the drug trade and the violence that comes with it. While this is the case for many young Black people, drill is often seen as a legitimate way out – GRM and Linkup TV’s YouTube channels, as well as the charts and its international reach indicate that appeal. But with the increased criminalisation and censorship of the sound, the police are creating an environment that makes it difficult for artists to create and express freely.

“Counting up this money from O or money from shows / Man's counting up both / Paps need a pattern business and a pattern up home / Man patternin' both / Feds draw me out for a works and smoke / Tryna do me for both,” Headie One on Both.

Form 696 was the ideation of that more covert approach to censoring underground Black music, but it was still violent nevertheless. In 2017, I reported for The Guardian on Form 696 being scrapped as a necessary risk assessment form that venues had to provide police. However, many drill MCs have reported that they’ve had shows cancelled due to police putting pressure on venues by threatening to remove licenses. Skengdo x AM were the first to be given an court-ordered injunction that prevented them from performing certain songs, while other MCs such as Rick Racks have been prevented from using the words ‘bando’, ‘connect’ and ‘trapping’. Almost ten years on since the London Riots in 2011 and as we’ve felt the impact of austerity, it’s become more abundantly clear just how much underground Black music has suffered. Many of these MCs are on the gang matrix, a database created by the Met Police in 2012 to identify and risk-assess people involved in gang violence.

Many organisations have campaigned against its existence, particularly since information was leaked causing a data-breach that could have led to fatal consequences. One of the criticisms of the gang matrix has always been that it doesn’t distinguish between perpetrator and victim, and the reality is that the majority of those on there are both. Statistics also show that many of those on the database have previously been victims themselves or inaccurately included due to association with known offenders.

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, otherwise known as Section 63, is well known for having a devastating impact on Britain’s wider nightlife scene and it’s been covered extensively how ravers were criminalised. In July of that year, 20,000 people took to Hyde Park in London to protest against the new act; many still lament the decline of the UK’s wider nightlife since but in public discourse regarding the matter, there’s often been an omission of the impact it had on Black people.

“Music blazing, sounding, thumping fire. Blood. Brothers and sisters rocking, stopping, rocking; music breaking out, bleeding out, thumping out. Fire; burning,” taken from Linton Kwesi Johnson’s Dread Beat an Blood.

Much of the music people were raving to was of Black origin, as were its creators, but where the disparity lies is the way in which policing measures are applied to all Black life. Since the beginning of lockdown in late March, the police have consistently ignored social distancing guidelines. 30,608 stop and searches were carried out in April, up from 23,787 in the previous month in London alone. April 2018 saw only 13,085 searches. Newham, Haringey and Southwark are among the top five boroughs in London most affected by Covid-19, and these three also saw the highest rate of stop and searches in April. While the majority of stop and searches are for drug-related offences, this practice has been tied to prohibition and Black music censorship in Britain for a century.

Surveillance in the UK and increased policing measures makes it much harder for the illegal rave scene to thrive in this day and age compared to over 20 years ago, the future of the country’s nightlife is still very uncertain but whatever emerges, it’ll be Black underground music that will be under threat. Dutchavelli’s attendance at the recent BLM protest and increasing reports of young people being harassed and falsely arrested for causing and/or inciting violence at the protests only highlights the state continuing the practice of using punitive measures to police which impede on our daily lives and existence.

Those enclaves outside of public view became increasingly important as the years went on, the art of hiding in plain sight was second nature to previous generations. For those who didn’t want to face the potential prospect of being denied entry or being harassed at Black-owned clubs, shebeens or shoobs became the predominant way for Black people in Britain to gather around music. I myself grew up in those intergenerational spaces that would provide the foundation for my raving experiences later in life, both positive and negative. In 1996, my openly racist neighbours called the police as my family had a gathering to celebrate my mother’s birthday. Despite only being seven years old at the time, listening out for sirens and banging on the door became a prerequisite for raving while Black in Britain.

However, fifteen years prior, a similar occurrence happened in New Cross where a party was being held, but it resulted in the catastrophic fire that killed fourteen young Black people aged between 15 and 22. Despite police not being able to find the perpetrators, many still believe that members of right-wing group National Front were responsible. It’s always been believed that the suspects have always been known to the police but, as we try to imagine our futures in Britain, the way in which the state has regarded Black life in the past and present serves as a reminder that wider intergenerational discourse must continue.

Our experiences with the police today are merely echoes of the past and it’s pertinent to our wider understanding of Black existence in Britain that these histories are acknowledged and passed on. At a time where our rights and liberties are being aggressively eroded, recognising how these patterns have emerged in the past will inform our futures in this country.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox