My mum loved Bruce Springsteen. She also loved The Beatles (especially George) and The Stones (especially Mick), and Elton John and Paul Simon and, perhaps not quite as ardently, Rod Stewart — he made her laugh — among the boomer stars of the classic-rock era. But Springsteen was her favourite. There really was no contest. She was silly for The Boss.

You might think there’s nothing remarkable in that. She was a boomer herself, born in 1950, six months after Bruce. Had she not died, in 2021, she would be 73 now, the same age as him. He was and is one of the most popular rock stars of their generation. Why wouldn’t she have been a fan, even singled him out for special attention, as so many others have done?

Well, you didn’t know her. If you had, then her passion for Springsteen might have seemed to you, as it sometimes did to me, an unlikely predilection for a woman of my mother’s tastes and inclinations. Springsteen is a blue-collar megastar from the New Jersey shore, whose turbocharged epics hymn the hardscrabble lives of working men and women in America’s Rust Belt. My mum was an English schoolteacher, from a relatively genteel background. She grew up in Kensington and as an adult she lived a quiet, gracious life in the leafy suburbs of southwest London. She did not sweat it out on the street. That famous barefoot girl from “Jungleland”, sitting on the hood of a Dodge, drinking warm beer in the soft summer rain? That was not Susan Bilmes. She’d have been wearing court shoes over opaque tights, perched on a sofa in a conservatory, sipping Earl Grey tea, re-reading an Iris Murdoch novel. Maybe I’ll allow that it was summer, and the rain was soft.

My mum was no one’s idea of a rock chick. She didn’t drink beer. Never took drugs. Never smoked. She never once went to America. Had no interest in cars. Didn’t wear denim. Besides Bruce, she liked dog-walking (Labradors), Radio 4, World War I poetry, English gardens, Restoration comedy, Hannah and Her Sisters, The London Review of Books, watching tennis, visiting art galleries. Had she attended a festival, it would have been Glyndebourne. Maybe Hay. Her other enduring fantasy heart-throb was DH Lawrence; she once dragged her querulous brood around various points of interest — interest to her — in the former pit town of Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, birthplace of the sainted DH. When she made a commitment, she was going to see it through.

(I’m making her sound too prim: she also loved EastEnders, Hello! magazine and anything at all with Harrison Ford in it. She wasn’t above the occasional McDonald’s. Or a second G&T. When I was chucked out of school at 16, for drugs, she said, “What’s wrong with you? Why can’t you have sex if you’re bored?”)

I inherited a few of her interests (dogs, literary fiction, low-rent celebrity tittle-tattle) but not many. On Bruce we were in perfect harmony. She came to him relatively late, mostly because during the decade from 1973, when the first of her three sons (me) was born and Springsteen’s career achieved lift-off, she was too busy bringing up us boys, and cooking and cleaning and running our household, and pacifying a disputatious husband (my father), to pay close attention to new developments in American rock. The idea that every teenager in the 1960s was an habitué of Swinging London, and every young adult in the 1970s was popping pills and swapping spouses and seeking enlightenment in Eastern mysticism is, my mother would have been obliged to correct you, for the birds, and the credulous rockumentaries.

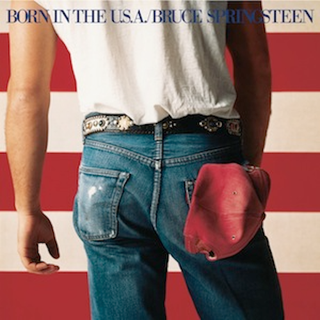

Bruce arrived, for Susan, in 1984. You can’t start a fire without a spark, and hers was Born in the USA. She was 34 that summer, I was 11. She bought it on cassette from Earfriend on Teddington High Street, and we played it every day in the car, a custard-yellow Citroën that was forever stalling at the lights; no hemi-powered drones screaming down boulevards for us. Her favourite track was “My Hometown”. (Seems like there ain’t nobody/ Wants to come down here no more.) Mine was “Glory Days.” (Yeah they’ll pass you by.) Those songs are elegies for a lost world, written before its departure. They rage against the dying of the light even as the sun is still rising. Springsteen is rock’s great nostalgist. Now he appears implausibly youthful and dynamic, but as a young man he seemed prematurely middle-aged — as my mother did.

From Born in the USA, my mum and I travelled backwards to the brooding Darkness on the Edge of Town and further back to the operatic Born to Run, the album that made him a phenomenon. Later, she followed him through the lovelorn Tunnel of Love, his divorce album from 1987, and beyond. I’ve known lots of people who have claimed to like Bruce Springsteen. I’ve not known all that many like my mother, who knew all the words to Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ, his uneven debut — and not just “Blinded by the Light”, either. Still, Born in the USA remained her touchstone, the foundation text of her personal cult of Bruce.

(Rock snobs can be sniffy about Born in the USA. They prefer its predecessor, the downbeat Nebraska. As so often, they’re wrong. Nebraska is a cracked murmur, diffident and withholding. Born in the USA, misinterpreted at the time as a jingoistic assertion of Reaganite “values”, is a righteous, barnstorming cri de cœur, a danceable lamentation.)

What was it about The Boss that so captivated her? She fancied him, certainly. He was handsome — still is — and masculine, and poetic, and he wore his heart on his sleeve, when he was wearing sleeves, which was (pleasingly, to my mum) not all that frequently.

But that was only part of it. I can’t say for sure, because we didn’t sit around analysing the reasons why his stuff spoke to us, and she’s not here now to be asked, but I think it’s because, as richly detailed as they are, Springsteen’s songs deal in universals. He is both the bard of the heartland and the most novelistic of songwriters. He uses specific, hard-luck stories of men called Scooter and girls called Bobby Jean, laid-off refinery workers and faded homecoming queens, to capture the ways we all feel about love and loss, and what it means to have parents and children and a marriage. Difficult parents, problematic children, a challenging marriage: even if she never rode in a sleek machine or lived in a shotgun shack, my mum had all of those. Springsteen knows that no one’s life feels small or insignificant to them, or to the people who love them.

He deals in catharsis, and if, occasionally, the sweat-soaked sincerity can veer across the midnight highway and come perilously close to self-parody — the mawkish petrolhead satirised by Prefab Sprout on the disobliging “Cars and Girls” — still millions of us are happy to take that ride. Secular sainthood suits him. He believes in the healing power of good-times rock’n’roll. He appeals to our jaded, compromised, careworn selves to remember the younger, idealistic, uncorrupted people we used to be. You got a problem with that?

It was summer, and the rain was soft. At precisely 7pm on a Saturday night in July, with minimal fanfare, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band ambled onto the stage of the British Summer Time festival in London’s Hyde Park, acknowledged the applause and the wolf whistles and got straight down to business. Standing in the crowd with my wife felt, for me, like an act of commemoration — a very public, entirely private memorial to my mum. This was my first opportunity to see Springsteen play live since her death. And since it is through his songs that I can most easily feel close to her again, since I can’t even look at him without being reminded of her, I was primed for conflicting emotions. Joy, and pain. Like sunshine, and rain. Both of which heaven allowed.

Boys do cry. I’m one of them, and so is Bruce Springsteen. On this occasion I managed to survive two full songs without weeping — pretty good! — but at the opening bars of the rabble-rousing “No Surrender”, the first of six songs he played from Born in the USA, the dam burst: Well, now young faces grow sad and old/ and hearts of fire grow cold/ We swore blood brothers against the wind/ Now I’m ready to grow young again. It felt overwhelming and consoling and sad and wonderful. Too much, and not enough.

The tears dried eventually, as tears do, and despite the occasional lump in my throat (“Glory Days”), the concert for most of its duration became just that: a warm, funny and raucous showcase for the talents of a band that, at 52 years young, is still in absolute control of its material, its environment, and its audience.

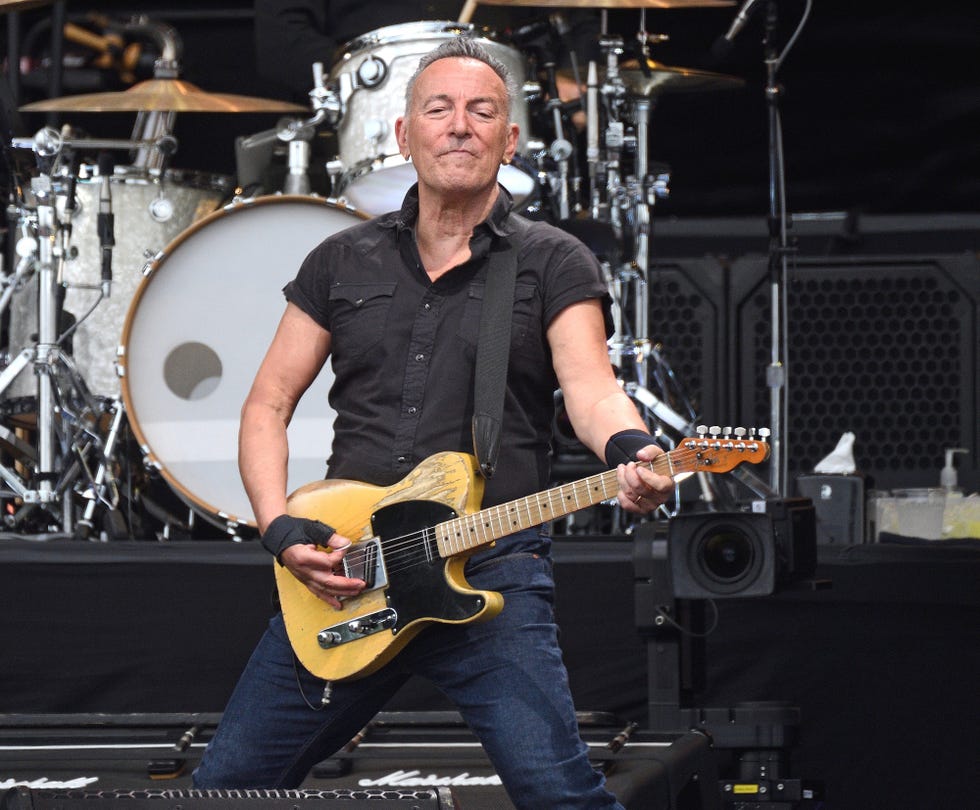

Looking insanely well-preserved in a black shirt, jeans and oxblood DMs, battered Fender slung over his shoulder, Springsteen capered, he clowned, he grinned and he grimaced, he posed for selfies, he wiggled his bum, he ripped open his shirt to reveal the chest of a man a third of his age, he told stories of his past, he played the rock’n’roll revivalist preacher to the hilt: everyone was welcome in the tent, and if Hyde Park had a roof, he would have blown it off.

For all the swagger, this was a show with a theme, and that theme was mortality. Springsteen and the E Street Band have, as you would expect at their ages, known grief, and they mine it unapologetically. A section of all their shows honours fallen keyboard player Danny Federici, who died in 2008, and saxophonist Clarence Clemons, who died in 2011. (These days, the sax is played, brilliantly, by Jake Clemons, Clarence’s nephew.) “Last Man Standing” was dedicated to George Theiss, who, until his death in 2018, had been the only other surviving member of The Castiles, the band Springsteen joined at 15. By now, Bruce himself was weeping.

Those famous songs he wrote in his twenties and thirties, he’s grown into them. And we’ve grown into them too. I loved them as a kid, but they mean more to me now than they did then. How could they not?

When the rain came, the intensity grew. Sporadic showers at first, but then big, fat blobs started to fall just when, as if by magic, the band launched into “Mary’s Place”, with its joyful refrain: “Let it rain, let it rain, let it rain…”

And there he stood, magnificent. And there we stood, transported. Also, wet. Also, alive.

It rained on the day of my mum’s funeral, too, in the middle of what I hope must count as the grimmest January of most of our lives. She died on New Year’s Day, in a care home on the south coast, where she had spent her final years. We sent her on her way two weeks later, from a crematorium in west London, a short bus ride from where I live now and bring up my own children.

Days earlier, England had entered its third lockdown. The Mayor of London announced a “major incident”, saying that Covid cases in the capital were “out of control”. We were told by the Chief Medical Officer to stay at home and “act as if you have Covid”, even if you hadn’t.

Government-mandated restrictions dictated that only close family members who had tested negative should attend funerals, and then they were to remain socially distant. (I’m sorry, but I would consider it a dereliction of duty if I did not, at this point, make the standard-issue English-family joke here, and point out that we’d been socially distant from each other for years, so this wasn’t a tricky rule to observe.)

My brother Nick, who lives in Oslo, in Norway, was prevented by law from flying to London to attend the funeral, so he and his family had to watch on a video link. I’d planned to say a few words at the service but my Dad was keen to deliver the eulogy, which seemed only right and proper, and then my other brother Christopher, the youngest at 43, also wanted to speak. So I decided I’d keep my remarks to myself, lest the occasion turn into a Springsteen-style three-hour marathon.

And I would have left it that way, and I really hadn’t given it much thought, until the Hyde Park gig. Springsteen brought it out of me, as he has brought this piece out of me.

So what I would have said (among other things) at my mum’s funeral, if I hadn’t decided not to, was that in the days immediately after her death I spent a couple of evenings looking up Springsteen lyrics online, searching for the most appropriate phrases to quote from one of the songs my mum and I sang along to in the mid-Eighties, when I knew her best and was, I now realise, closest to her.

But that winter, trapped at home like most of the rest of the world, I’d been listening to Springsteen’s most recent album, Letter to You, which was released in 2020, in the teeth of the pandemic. And even though my mum would never have heard it — Covid killed her, but she had been fading away for a few years, from early-onset dementia — there was a song on there that seemed to nail something of how I felt about her death.

It is a simple lyric, guileless, of no obvious literary merit, but heartfelt, plain-speaking and imbued with a steely faith, like all the best of Springsteen’s stuff. Not a faith that is associated with a specific organised religion, necessarily, but rather a numinous spirituality, which my mother certainly had, and a belief in the endurance of the human soul. Even if you don’t believe in life after death — as I don’t — and you are sceptical about the definitive existence of such a thing as a human soul — as I am — you can share Springsteen’s feeling, expressed here and elsewhere, as well as from the stage in Hyde Park, that those we love live on, in us.

That Saturday night in July, as a final encore, darkness having enveloped us like a shroud, Springsteen emerged alone from stage left, with an acoustic guitar, and he sang the song I might have read at my mum’s funeral, if things had worked out differently. And now I don’t mind that I didn’t read it then, because in front of 65,000 people, in the heart of the city where my mum was born, just a few miles from the house she grew up in, just a few more miles from where she and I heard him first, Bruce did it for me, and for her. That’s how it felt to me.

The song is called “I’ll See You in My Dreams”, and it goes like this:

The road is long and seeming without end

Well days go on, I remember you my friend

And though you’re gone and my heart’s been emptied it seems

I’ll see you in my dreams

I got the old guitar here by the bed

All your favourite records and all the books that you read

And though my soul feels like it’s been split at the seams

I’ll see you in my dreams

I’ll see you in my dreams, when all our summers have come to an end

I’ll see you in my dreams, we’ll meet and live and laugh again

I’ll see you in my dreams, yeah up around the riverbend

For death is not the end

And I’ll see you in my dreams