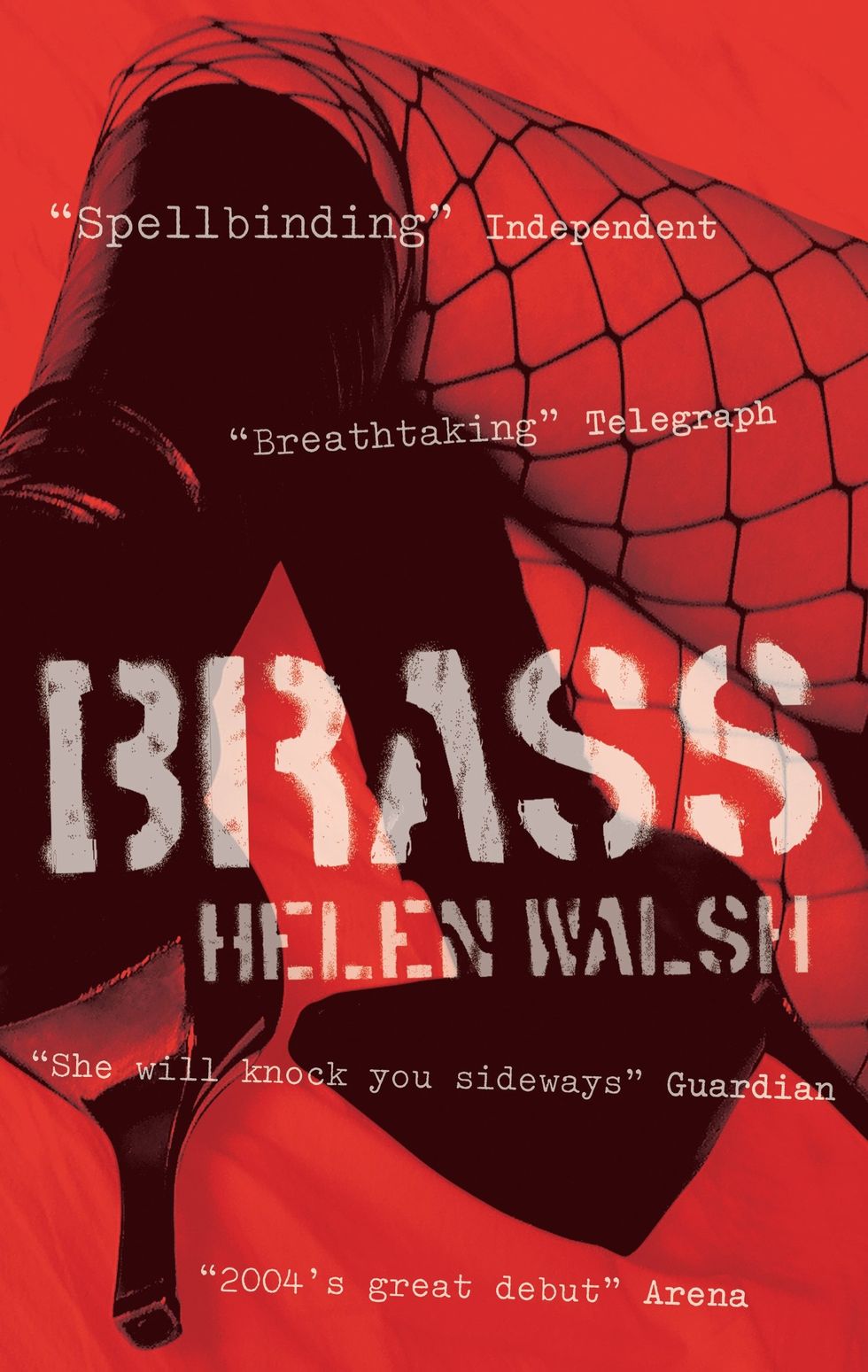

In the spring of 2004, there was only one book being published. At least, that was how it felt to me. The noise around Helen Walsh’s Brass was ambient, inescapable. The author had been breathlessly profiled in a number of broadsheet papers, as part of the carefully coordinated PR campaign I’d once assumed to be the due of any debut novelist. Walsh [pictured above] was cat-nip to journalists, for obvious reasons. She was young and beautiful and clever. She came with an intriguing back story and a suite of provocative opinions. She was an early exemplar of the author-as-brand, a person more interesting than the writing she produced. The book itself occupied a tricky hinterland: insufficiently complex to be classed as literary fiction; too smart to be dismissed as chick lit. But the subject matter was titillating and the paying public bit. Brass is a bildungsroman with a difference. Its heroine is hooked on cocaine and bought sex. The plot tracks her progress from putative self-destruction to something like peace.

It was famous for its verité sex scenes, though it was the unvarnished nature of the main character that really stayed with me. Millie is dreadful. It’s a testament to Walsh’s verve and skill that readers remain with her until the final page. I have read Brass more than once, and I feel something new every time. On my last reading, I kept thinking how it would never be published today.

Poor Millie would be spayed by a sensitivity reader quicker than you can say “problem-atic”. An ambiguous scene where she sort of assaults an abused girl in a disabled toilet would be struck through with a red pen. Her friendship with Jamie, a man eight years her senior whom she met when she was 13, would be filed under “weird”. Her stated preference for whores who look dirty and drug-addled would be flagged. As would the word whores, for that matter, along with the titular brass. They’d probably be swapped for a more anodyne term, like “sex worker”, and its comforting implication that prostitution is just another job, like waitressing, or delivering post.

In 2004, these were non-issues. I disliked Millie because I’d met her type before. She was a sex traitor who spent all her time sucking up to men, then complained that girls were mean. In the intervening years, Gillian Flynn and the internet furnished me with the language and I can now categorise her in a few short words. She was a Cool Girl, a Pick Me, a Not Like Other Girls Girl. She was labouring under a misapprehension once rife among young women. Namely, that if you acted like one of the boys, they’d be fooled into thinking you were one of the boys, and you’d be spared the routine con-tempt dished out to ordinary chicks.

In addition to this, she didn’t feel like a proper person. I have yet to meet a real woman who displays the same appetites for anonymous sex and unlubricated anal. She is a male fantasy figure, an FHM reader’s fever dream. Nicola Six minus the death wish and post modern pretensions. This is perhaps the best way to read Millie: she is less a realistic character than the personification of a moment. An emblem, like Lady Justice or Marianne, forged in the crucible of raunch culture. At the turn of the 21st century, women were expected to collude in their own debasement; to join their boyfriends at strip clubs, bare their bodies on Girls Gone Wild, take pole-dancing lessons, enact a kind of mimic lesbianism for men. The obligatory noughties uniform — Brazilian wax, visible thong, ratty blonde extensions, breast implants like halved grapefruit — was borrowed from pornography. It was not meant to look nice, but to denote commitment to a cause: the cause of being hot. A woman wearing this kit could be read as a team player, ready to put male gratification before her own comfort.

Ariel Levy skewered these attitudes only a year later, in Female Chauvinist Pigs. It is a strikingly prescient book, deploying a level of perspective more usual in work published long after the fact. In it, Levy interviews countless women: schoolgirls, lesbians, tour managers, TV executives. All are prepared to throw their own sex under the bus to win a few crumbs of male approval. Curiously, given that the pornification of mainstream society was sold as an article of female empowerment, men still seemed to control everything in 2005.

“Women who’ve wanted to be perceived as powerful have long found it more efficient to identify with men than to try and elevate the entire female sex to their level,” Levy notes. “Raunch provides a special opportunity for a woman who wants to prove her mettle...

Participating is a way both to flaunt your coolness and mark you out as different, tougher, looser, funnier — a new sort of loophole woman who is ‘not like other women’, who is instead ‘like a man’.”

Once you understand this, Millie looks rather less rebellious. She is not a freewheeling sexual mercenary (per her own words, a “genderless freak”). She is a good soldier, who has imbibed the spirit of the era. Her tendency to objectify other girls is not an aberration, but a common, culture-bound syndrome, one many of her contemporaries were forced to suffer through. Her porn-sick musings are not authentic expressions of desire, but mindless echolalia, reminiscent of RD Laing’s remarks about schizophrenics in colonised nations. Laing noticed the voices they heard rarely spoke in their own language. They talked in the oppressor’s tongue.

Is it too much to hope the discourse has moved on, that girls no longer feel the need to mouth male sentiments and claim they’re speaking from the heart? I have aged alongside Brass, so can only guess at the mad contortions they’re required to strike these days in order to be deemed desirable. I do know that Walsh’s most famous protagonist captured everything awful about being female in 2004. Twenty years on, Millie already feels like an article from a bygone age, but a quick flick through the book will cure any nostalgia. The conditions in which she was created were horribly real. And no woman in her right mind would want to go back.

Tabitha Lasley is the author of the memoir Sea State. This piece appears in the Spring 2024 issue of Esquire, out now.