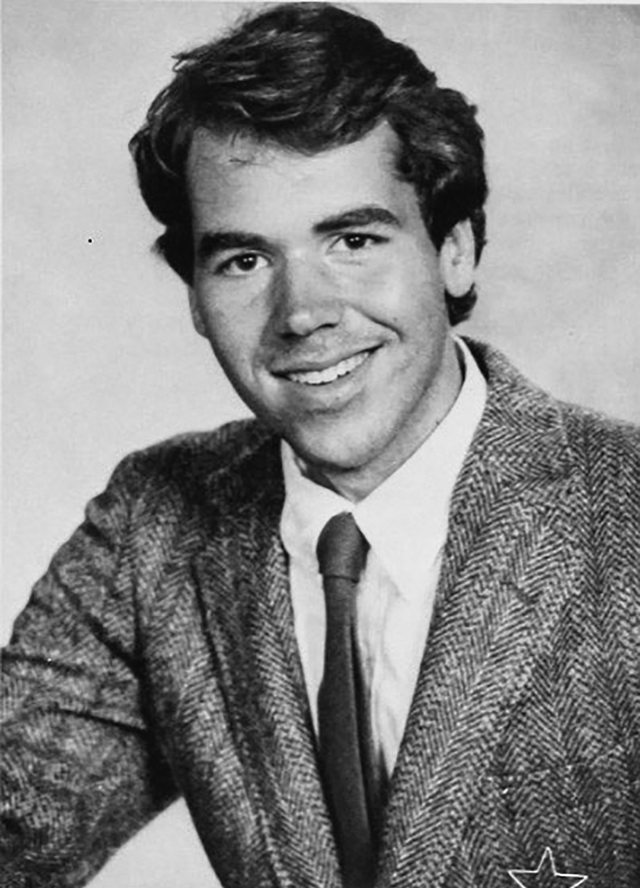

It’s 1981. Bret Ellis is 17, a senior at Buckley, an exclusive prep school for the entitled offspring of wealthy Los Angelenos. An only child, Bret lives in splendid isolation on Mulholland Drive, in a house overlooking the San Fernando Valley. He has a Latina maid, Rosa, and a dog, Shingy, and a girlfriend, Debbie, all of whom he keeps at a distance. His parents are absent, emotionally as well as physically, away on a months-long trip to Europe.

Bret runs with a fast set. He drives a Mercedes 450 SL, when he’s not driving a Jaguar XJ6. He drinks vodka grapefruits, and munches his mother’s Valium, takes bumps of Debbie’s cocaine, and scores Quaaludes by the bag. He is an obsessive consumer of movies and pop music and fashion, his tastes for the most part blandly conformist Young Republican: Polo shirts, collars up; tennis shorts; Topsiders with no socks; Wayfarers. He keeps a record of the movie stars he fantasises about while jerking off: Richard Gere, Mel Gibson, Dennis Quaid. He has athletic sex with classmates, all of whom are porn star hot. (There are same-sex encounters in Ellis’s previous work, but The Shards might reasonably be described as the author’s gay novel.)

Bret’s world is superficially glamorous and aspirational, and existentially horrifying and depressing. “What did it matter, what did anything matter, nothing mattered,” he reflects, in the moments after he’s been sucked off by Debbie, while thinking about his friend Matt Kellner, “naked and wet, on his knees.”

Alienated, apathetic and anxious, Bret yearns to escape LA, and the stifling atmosphere of monied ennui. He wants to be a writer, and is working on a novel, to be called Less Than Zero. But his life is about to be thrown into chaos by the arrival of a new boy at Buckley. That the newcomer is rich, tan, toned and handsome hardly marks him out from his peers. But something is off about Robert Mallory. Bret senses it even if his friends don’t. Robert Mallory is a liar, and a fake. But then, Bret is a liar, and a fake. Bret is a writer.

Coincidentally, or maybe not, a murderer, nicknamed the Trawler — ski mask, butcher’s knife — is abducting and killing teens in ritualistic ways too gruesome to mention. (Don’t worry, this is a Bret Easton Ellis novel: you won’t, ultimately, be spared the gory details.) None of Bret’s friends seems too concerned about this — “No one talked about it. No one seemed to care” — but he is transfixed. Then one of their group, a beautiful stoner with whom Bret was secretly sexually involved, goes missing, later found dead. Again, after the initial shock his friends absorb this news with remarkable equanimity. Not so Bret, who has, meanwhile, become preoccupied by the activities of a darkly mysterious hippie cult, the Riders of the Afterlife, currently terrorising LA. Could all these be somehow linked — Mallory, the Trawler, the cult — or is everything in Bret’s head? Is he paranoid? Is he hysterical? Seriously, what’s wrong with Bret?

Periodically, he tries to fit in, to play his part in the movie, to be a loving heterosexual boyfriend, a caring friend, an engaged student. This persona he calls “the tangible participant,” cousin to another, “the actor”. But he can’t maintain the fiction for long.

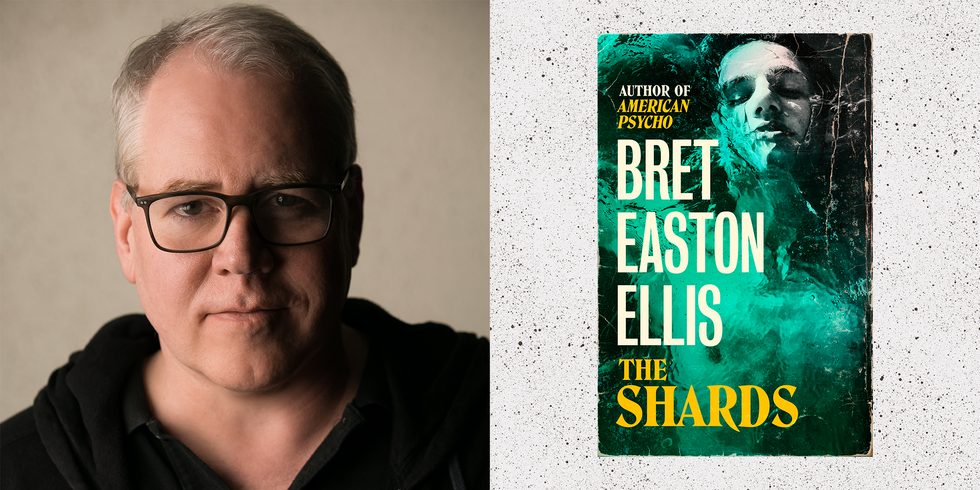

Bret Easton Ellis’s The Shards — his sixth novel, and the first in 13 years — is, among other things, a serial killer thriller set in LA in the New Wave 1980s, the period just before Less Than Zero, his mesmerising, polarising debut, published in 1985, when he was 21.

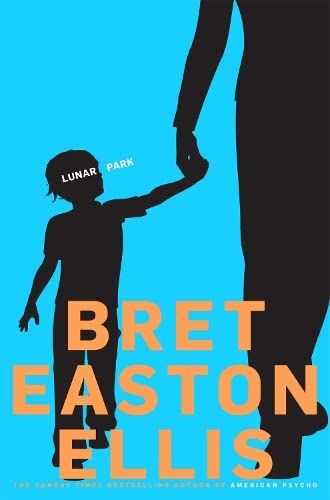

It is lurid, grisly, violent, sexy, explicit, ambiguous, chill, funny, sad, and creepy, and so perfectly Bret Easton Ellis-y that at times it flirts with self-parody — which, one suspects, is very much the idea. It’s hard to avoid the cliched poster-quote: if you like Bret Easton Ellis novels you’ll love this. If you hate Bret Easton Ellis novels this won’t persuade you otherwise. If you’ve never read a Bret Easton Ellis novel, starting here won’t hurt, but you might have even more fun if you first mainline the classics: Less Than Zero; the electrifying American Psycho (1991), his Wall Street slasher masterpiece; and, wildest of all, Lunar Park (2005), a metafictional freak-out that is also a horror story about an evil doll.

Ellis is a tease. As his career has developed, in fits and starts, so his project has deepened: his novels are deadly serious social satires masquerading as generic pulp workouts, the literary equivalent of Forties B movies, or perfect three-minute pop songs, or shock-and-awe fashion shows — disreputable, disposable, apparently meaningless artifacts that can rearrange your chemistry and make you see the world anew. In their surface is their depth.

From the beginning, Ellis has summoned a series of lost boy narrators to tell his stories — Clay in Less Than Zero, and again in Imperial Bedrooms (2010); Sean Bateman in The Rules of Attraction; Sean’s brother, the notorious Patrick Bateman, in American Psycho; Victor Ward, the model-slash-terrorist in Glamorama (1998); older Bret in Lunar Park, and younger Bret in The Shards — and invited readers to speculate on how close to him, and to each other, they are, and how true to the author’s own experiences are the events they document.

The writer to whom the young Ellis’s work was most often compared was Joan Didion: the coolly limpid prose; the stunned, sun-bleached Southern California minimalism. In The Shards, Bret defines his literary ambition as an attempt to capture a sense of anomie specific, he feels, to LA in 1981: “Numbness as a feeling, numbness as a motivation, numbness as the reason to exist, numbness as ecstasy.”

American Psycho, his forensic satire of late capitalist consumption, was hardly sui generis, although literary fiction had never come so close before to grindhouse horror. Glamorama was a pyrotechnic conspiracy thriller about the cult of celebrity, Robert Ludlum on coke. Lunar Park was closer to a Stephen King ghost story than to anything Didion ever wrote. As well as middlebrow genre fiction, that novel and The Shards play fast and loose with various degraded literary modes — metafiction, autofiction.

Inhaling these novels, Ellis’s readers became accustomed to the metronomic repetition of brand names, band names, street names, the names of minor characters, reeled off like shopping lists. Some find this stuff confounding, or boring, the rest of us lie back and surrender to the ride. To some extent, the trick with Ellis’s fiction is to let it wash over you. It’s a mood, a vibe.

All of Ellis’s novels have elements of memoir, the more recent ones especially: like the rest of us, he’s getting older. But a novel, Ellis tells us, is a not an autobiography. A novel is “a dream that asks itself to be written”. (Are dreams real?) A novelist’s duty is not to record what happened, but to conjure what it felt like.

In The Shards, after a violent altercation in a hip nightclub in which a girl is attacked by an intruder, Bret, the proto-novelist, finds himself “calmly elated”: “This was something I could write about, this was an incident I could place in the narrative of the novel I was working on, and I began to think of ways to embellish it — paint it darker, give it an eerier vibe, push the evil.”

Preparing for a meeting with a movie executive who might want to commission a screenplay from him, Bret briefly, flippantly, outlines the pitch he has in mind: “A boy, his friends, young people in LA, sexy, a little bi, drugs, someone is killed, there is a chase, violence and bloodshed, a mystery the boy solves or maybe not, I preferred the downer ending but we could make it upbeat as well, I’d offer, we could negotiate that.”

Shards are what you pick up off the floor after something fragile has been smashed. Shards are what you glue back together to make the shattered object whole again. Shards are flashes of light, discrete pieces of information, fragments of memory. Shards have sharp edges. The Shards is, in some twisted way, nostalgic, a reconstruction of the past, a love letter, written in blood (fake blood? real blood?), to the LA of Ellis’s youth, in the era he calls “empire”: pre-internet, before the self-appointed gatekeepers of the culture — Hollywood, Washington, legacy media — lost control of the narrative, and everything blew apart.

The Shards began its life in 2020 as an audiobook, broken up into episodes and broadcast on the author’s podcast — and it sometimes reads like it. It has that propulsive quality that serialised Victorian novels have, with frequent cliff-hangers and reveals designed to keep readers and listeners yearning for the next instalment. It riffs on the signal genre of the moment — true crime — while insisting on its own artificiality. The Shards perhaps represents a new genre: true crime fiction.

Our culture finds murder, especially the murder of young good-looking people, as titillating as porn — though there is less shame attached to enjoying Dahmer (one billion views in 60 days on Netflix), than there is to clicking on Pornhub. Reading The Shards over New Year, as I did, it was impossible not to flash on the horrifying murders of the four students in Idaho, at the end of 2022, a story so instantly compelling — I hesitate to say “appealing”, though that’s what it is — it might have been invented for the streamers, or the Serial podcast.

For readers of my vintage and inclinations - pop culture obsessed Gen X over-consumers - Ellis remains a lodestar. What millennials and Gen Z readers will make of The Shards I can’t say. (I’m sure they’ll tell us.) Ellis is a deeply moral writer, an innocent as all true satirists must be, a perpetual adolescent driven by rage and despair at the cynicism of the adult world. Whether his unsettling affect, sincerity buried in irony — he means it, man — will jibe with contemporary dispositions remains to be seen.

He is also, before anything else, a stylist. His true interest is in words making phrases making sentences making paragraphs, and how those appear on a page (which is not the same as listening to them on your headphones) and whether they can summon the dream into life.

From The Shards:

“I made my way from the empty living room to the kitchen after reminding myself the party was taking place in the backyard and passed the long black granite counter lined with tequila bottles where Bruce Johnson and Nancy Dalloway were busy making margaritas in two blenders and filling plastic cups rimmed with salt that they placed on a tray Michelle Stevenson took outside to the backyard. On the kitchen table were the boxes of chopped salad waiting to be dressed and mixed, along with platters of glistening sushi. I opened the refrigerator to find a soda but it was almost completely stacked with Coronas and I didn’t see any Coke or 7Up, and after opting for a beer I said hi to Bruce and Nancy, who hadn’t noticed me previously, and then stepped into the backyard. The Tom Petty and Stevie Nicks duet ‘Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around’ which had been so popular that summer was playing from outside speakers and there were only about twenty people standing around and even though it was mid-October you could still sense traces of night-blooming jasmine, and the massive bougainvillea that sat off to one side of the yard was now dotted with a multitude of white Christmas lights and since it was a cool autumn evening the pool was heated and steam from its surface kept rising upward in tendrils toward the eucalyptus trees that bordered the brightly lit rectangle of blue water and obscured the darkened tennis court beyond it.”

It was this, the spell Ellis casts with his freewheeling sentences, the quality of secular incantation to his writing, that first drew many of us to Ellis, as much as the sex and drugs, and cool cars and beautiful bodies.

I still remember where I was when I read the opening passages of Less Than Zero, walking home from the bookshop holding the movie tie-in paperback (“The book that inspired the cult film”), over the bridge across the river, risking being run over by traffic as I crossed the roundabout, heading home, nose in the pages, 14-year-old body in suburban south-west London, imagination in Bel Air.

Ellis’s preoccupation is with aesthetics. His writing is decorous, but he has no interest in decorum. In common with the best writers, he won’t self-censor. And he is not, as his previous book, the patchy non-fiction collection White, took pains to make clear, politically correct. Given the opportunity to remedy or retract the supposed excesses of his previous work, most infamously American Psycho, in The Shards Ellis doubles down on the bloodletting. There is, mercifully, no attempt at retrofitted diversity, or pandering to contemporary sensitivities. As the world was experienced by a rich, horny, disaffected young white man in LA in 1981, so it is presented in The Shards.

In one scene, set in a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel, a prominent middle-aged film producer in a bathrobe initiates a casting couch-style seduction of a teenager hoping to break into the movie industry, an event later rationalised by the “victim” as no big deal: “It hadn’t bothered me in any substantial way… yes, I was technically “underage” but no one had hurt me. I hadn’t been assaulted. I let it happen.” And who’s to say that wasn’t how it was? “Fucked up is relative,” as Bret remarks later on.

The only people of colour in The Shards are one-dimensional minor characters, in subservient roles, their interior lives unexplored. Everyone is objectified. All relationships are transactional. Everyone, including the author, is apolitical. Identity politics do not impinge. Identities are unfixed, and have always been since Less Than Zero. Is Bret gay, or bi, or something else? He doesn’t say, perhaps he doesn’t care, maybe labels are not important.

The most stable identities are those constructed from luxury items — fast cars, expensive clothes — and reinforced by tastes in music and movies, restaurants and real estate. Ellis’s books are about the commodification of personality, even of feeling, and the life-styling of experience.

The result of all this is that readers new to Ellis may find The Shards “ick” or “cringe” or even “triggering”. (Novels are supposed to trigger something, aren’t they? But perhaps I’m missing the point.) Those who disapprove should reflect on the fact that for as long as he’s been writing Ellis has risked scorn and objection, from Left and Right both. Prominent feminists have denounced him. Family values advocates have condemned him. The American literary establishment has blackballed him. Even Hollywood, as amoral a town as any in history, seems to find him hard to stomach. If cancel culture had existed in 1991, when American Psycho first appeared, he’d have been cancelled long ago.

I suppose the cruellest fate, almost too awful to contemplate for a provocateur of Ellis’s reputation and achievements, would be to have his new work ignored. I think that’s unlikely. The Shards is queasily gripping, strikingly heartfelt, and a whole lot of fun. The novel does not deserve to be overlooked, though stranger things have happened, as anyone can tell you who has ever cruised the Hollywood Hills alone, late at night, a little buzzed, listening to the coyotes howl in the canyons, feeling glad to be alive one moment, and frozen with dread the next.

The Shards by Bret Easton Ellis is published by Swift on 17 January.