Emily Ratajkowski’s My Body has the urgency of a note slipped through the bars of a gilded cage. A collection of 12 essays, discrete memoirs colliding the personal and the political, the book is a reckoning with a success that has brought its author pain as much as pleasure. It is a critique of the ways we commodify the female body, written by a woman whose body is among the most lucratively commodified in the world. It is an account of what Ratajkowski describes as an “awakening.” It is pointed, occasionally caustic, and frequently troubling.

My Body begins in 2013, when Ratajkowski, then 21, found instant fame, as well as a measure of notoriety, dancing in a music video for the biggest hit single of that year, “Blurred Lines”, by Robin Thicke. Two versions of the video were made, at a studio in Los Angeles: the “official” version, in which Ratajkowski shimmies and clowns in a crop top and plasticky shorts; and the “unrated” version, in which she does the same, topless. As its makers surely hoped it would, the videos went viral — when that meant something less frightening than it does today. At the time of writing the censored version has accumulated 721 million views on YouTube. For all those who applauded, and pressed “play” again, many others were appalled.

In the “Blurred Lines” videos, Ratajkowski and Thicke are accompanied by his co-writers, the rapper TI and the megastar Pharrell Williams, and two other women, Elle Evans and Jessi M’Bengue. While the near-naked women gyrate, the men don’t so much as remove their jackets. Thicke, not an immediately loveable figure, even before we got to know him better, wears a business suit, designer stubble, aviator shades, and a smirk.

As much as her performance, and her appearance, it was Ratajkowski’s defiant reaction to those who accused the video of misogyny that transformed a moderately successful swimwear model into a lightning rod for debates about representations of women in pop culture, in traditional media, and online.

When, in 2013, Ratajkowski defended her participation in the “Blurred Lines” video as a statement of feminist empowerment, she meant it. It was her body, and how dare anyone else tell her when or how to display it?

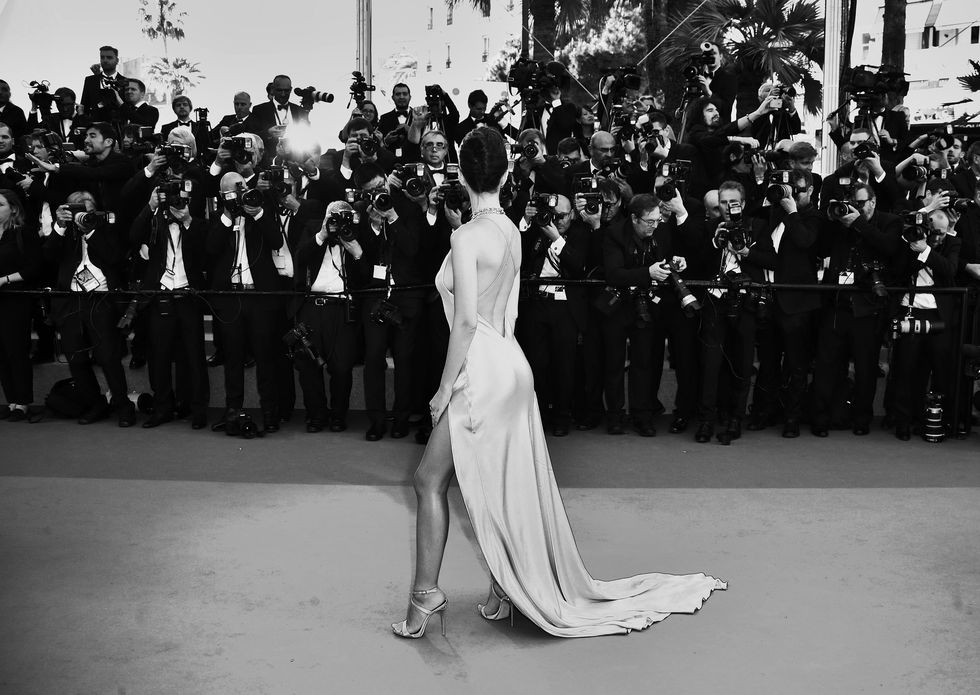

She went on to a phenomenal career. She has appeared on countless magazine covers. She has acted in movies; she was Ben Affleck’s mistress in Gone Girl. She has walked in fashion shows. She owns a swimwear brand, Inamorata Woman. She is that signal figure of the age: an “influencer”, with 28 million followers on Instagram, and counting. She even has a nickname, recognised around the world: EmRata.

Around four years ago, Ratajkowski began to acknowledge, privately, that the feelings of shame and self-hatred she had been struggling with were direct consequences of the position she occupied in the culture: a sex object, and a traumatised victim of exploitation and abuse. An example: the idea that she had been “empowered” by “Blurred Lines” was undermined, she writes, by the fact on the set of the video, she was groped by Robin Thicke. [When contacted by Esquire, a spokesman for Thicke declined to comment.] One way for Ratajkowski to try to reconcile all this was to write about it.

In September 2020, in New York magazine, Ratajkowski published a blistering essay, included in the new collection, entitled “Buying Myself Back”. As much as a magazine article can be, it was a sensation, and it is a large part of the reason for the excitement around the publication of My Body.

Raised in San Diego, California, the only child of an English professor mother and a high-school art teacher father, Ratajkowski, now 30, lives between New York and Los Angeles with her husband, Sebastian Bear-McClard, a film producer (he made the excellent Uncut Gems with the Safdie brothers) and their son, Sly, who was born in March.

I spoke to her on a Zoom call in August. It was early morning in LA, and she’d already been up for hours, taking care of her baby. Composed, even serene — certainly poised enough to make me hyper-aware of my own fidgeting — she was positioned on a sofa in a plain white blouse. Our conversation kept circling the same points. Her success has been a gift, in that it has brought her money and fame, and now a platform for her writing. It has also been a curse, in that it derives, in the main, from her looks, and the fact that they are the kind of looks that appeal most directly to men.

At one point I mentioned to her that the fact she has written such a searching book was a gift to headline writers: “EmRata Reveals All!” She smiled politely.

ESQUIRE: You grew up in sunny Southern California. The cliché is of a place where good looks and the body-beautiful are worshipped even more fervently than they are elsewhere. Do you think that affected the way you feel about your own appearance and the attention it brings you?

Emily Ratajkowski: Definitely. I went to a public high school that didn’t have a football team, it had a surf team. The culture is stereotypical in that way. As a teenager, you can’t go to bars or clubs, so it’s really house parties and spending time at the beach. That’s what you do in the summer. And that means you are in your bathing suit a lot. And I do think that there is an emphasis on bodies and physical beauty. Certainly I very much remember that when I was 14/15 I was already thinking about how my body was going to look in a bathing suit, in a really serious way.

You write about having had male attention on you from when you were barely in your teens.

I have a very visceral memory that I didn’t write about in the book of going to the beach with my first boyfriend and wearing a bathing suit, and older men yelling at me and saying something about my ass. I was like 14. I was embarrassed, and I was humiliated for my boyfriend, and I remember trying to go up and yell back at them and them saying to me something like, “You wear something like that, what do you expect?” It was already complicated. I knew these 40-year-old men were not supposed to be doing that, but on the other hand, of course I did want male attention.

You grew up not too far from LA, where beautiful young women are fresh meat for the entertainment industry. Rather than running away from that, you decided, as you put it, to capitalise on your looks.

I think I was super-aware of how expensive life was, of how expensive college was going to be. I had a bunch of friends who worked in the service industry, making minimum wage. Money seemed really important — which it is! Ha! And I’d meet child actors and models, and their parents would tell my parents that their kid had enough money for college because they did three seconds in a commercial… I think for me and my parents it felt like we had to capitalise on this opportunity. It never felt like I was going to do this full-time or professionally. The other side is that of course I wanted to be considered beautiful. I had grown up worshipping women who were not only considered pretty but also sexy. And I wanted to be that, because it felt like the thing that made women different and powerful and special.

Your essay “Toxic” talks about the period when you were in your early teens and there were these young women — Britney Spears, Lindsay Lohan — running around LA, hugely famous, being pursued by the paparazzi, and

really they were being torn to pieces. And we all know what happened to some of them as a result. In that piece you describe Britney Spears as a warning. You were very young, I know, but it seems it wasn’t a warning you heeded.

At the time, it felt like [the tabloid attention] is the downside, yes, but the upside is everything. Like, “Sure, I guess all that sucks, but what sucks a lot more is being poor and living in your childhood bedroom.” It was easy to say, “OK, she’s having a breakdown but she’s Britney Spears. She’s so lucky!”

In retrospect, were you wrong about that?

I don’t know! I’m still grappling with that. I have a son and if he was interested in modelling, I would deter him. And the same for a daughter. So I guess the answer is, I don’t think that [those celebrities] are lucky. But at the same time I’m sitting in my home in Los Angeles talking to you. It’s nice to be able to buy a house.

Your essay “Beauty Lessons” is about learning about the way women are looked at and valued for their appearance from your mother, who is a great beauty herself. She has always been very proud of the way you look, and your ability to attract male approval, and she seems to have lived vicariously through you.

I’m always fascinated by mother-daughter relationships, especially beautiful mothers and daughters. In the industry, you see it. It’s a classic trope: the stage mom. But I don’t think women like to talk about it a lot because it’s super-painful. My relationship with my mother is so many things beyond beauty and the lessons I took from her. That being said, when I was looking back at my life and thinking, “When did I start to compare myself to other women? When did I start to think this is important?”, it became clear that so much of my early life lessons had come from having a beautiful mother and what beauty had allowed her in her life and how her beauty made her feel about herself. That essay is about trying to piece together all the tiny moments that impacted me and made me care about being seen as pretty.

I have to say it is quite rare to hear from a beautiful person who is prepared to discuss her own appearance and how she feels about it, and how the world treats her as a result of her looks. In my experience most beautiful people, women and men, refuse to acknowledge their beauty, or brush it off, or flat out deny it. You have chosen not to do that.

I actually would say that I don’t feel beautiful. There’s so many things that I’m insecure about. Partly because the world has made me aware of how I look at every single moment, from every single angle: which features I should be proud of, or less proud of. Which I think, by the way, is true for people who aren’t models. But especially for women. Women are very self-aware. That’s what I was interested in. I wanted to talk about the ways the world has responded to me, physically. I happen to be a model so it’s heightened for me.

I apologise, because this will sound ridiculous in the voice of an English man, but if it’s OK with you I’m going to read you something from your book.

This will be a first for me.

It’s about your early decision to pursue modelling: “All I had to do to fund my independence was to… strip down and get greased up in body oil, to pose suggestively in red lace lingerie or brightly printed bikinis I’d never choose to wear, pouting at the command of some middle-aged male photographer.” Now, I know you’re writing that with a certain amount of ironic distance but still, to me — and I imagine almost everyone else on the planet — that description of all you had to do sounds terrifying. Did you really think, going in, that it would be no big deal to take off your clothes and pretend to be sexy for some creepy older guy?

I think I felt like that probably up until about four years ago. Ha! I felt that it was a really great job compared to all the other jobs in the world. A great way to make money. And along the way I got these images that made me feel good about myself. And while yes it was totally terrifying, and there were many things that I write about in the book that deeply impacted me, and traumatised me, I did feel that this was a pretty uncomplicated transaction. And I think that a lot of women feel that way.

What happened four years ago that made you change your mind?

I started to realise I had all these anxieties around my work and my body, and it was exhausting. How hard I was on myself was just exhausting. My husband was like, “Why do you feel that way?” I really had to take a hard look at myself and say, “OK, this is why I feel the way that I do.”

In the Introduction, you write this: “I’ve capitalised on my body within the confines of the cis-hetero, capitalist, patriarchal world, in which beauty and sex appeal are valued solely through the satisfaction of the male gaze. Whatever influence and status I’ve gained were only granted to me because I appealed to men.”

That’s something that I still struggle with. I don’t know that people would have ever read my writing had I not been in the position that I am.

Your body, or rather your collusion in the commodification of your body, has brought you money and fame but also, as you go on to detail, a great deal of unhappiness.

I actually only realised this having finished the book and reading all the essays together, how much I’ve internalised the way the world sees someone who capitalises off of their body and becomes an object. It brought me a lot of self-hatred. And thinking very little of myself. And one of the reasons that I started writing this book was to remind myself that I’m more than just a body, a commodifiable asset. I think I had a pretty serious wall of denial up, for a lot of my twenties, around a lot of my experiences. I felt that what I was doing was empowering, and that I was an example of being a feminist, that I was someone who was able to work the system. [But] I got married, I got a little older, and that switched. I started to question where a lot of my anxieties were coming from, about my position in the world. I started writing to process those feelings.

“Blurred Lines” is the title of one of the essays in the collection. When, in 2012, you were wondering whether to take that job, you were reassured, in a misspelt email describing the director’s vision for the video, that it would be “FAR FROM MASOGYNIST” (sic). Do you think now that that wasn’t true?

No, it was not true.

The video is misogynist?

Yeah.

I watched it again, when I read your book. The imbalance is quite striking. They are older, famous, powerful, rich, and they’re wearing suits. You are much younger, unknown, and you are wearing next to nothing.

I agree. I had the same experience. I hadn’t watched the video since it had come out. I don’t think I probably watched it more than twice then. And I re-watched it when I wrote the essay, and I had the same reaction. I was very struck by how, in 2021, this video would not exist.

I asked myself that when I watched it. Because much has changed but… would it not exist now? Maybe it could?

So that’s why I start the book off [writing about the explicit 2020 Cardi B video] “WAP”. There are no men in suits in that video but it’s obviously women being hypersexualised. So I think that now we have new parameters but I’m not totally sure that things aren’t just as misogynistic as they were before. Ultimately, it’s about women sexualising themselves or being sexualised. That is how women are given power. That’s true, still, and that doesn’t happen for men in the same way. That’s just the truth. Now it’s TikTok and Instagram.

On the set of “Blurred Lines”, you write, Robin Thicke “did something he wasn’t supposed to do”.

He groped my breasts.

Have you spoken about that before?

No. I’ve never spoken about that before. I didn’t even remember it until much later. Five or so years later.

Is that telling, that you didn’t even remember it?

My life was about glossing over those kinds of moments. I’ve heard so many women talk about shrugging things off. [That kind of situation is] not something you choose to forget, it’s something that just is forgotten. I think now, looking back, I especially didn’t want to remember it because it would have been embarrassing for me. It would have been such a clear statement about my position. I didn’t want to feel that way. I wanted to feel that I was powerful and that being the girl in that music video was really important.

Was it hard to write about your experience on “Blurred Lines”?

Absolutely. That essay was one of the most difficult for me to write. I did not want to write it. Because all I’ve wanted was to not be known for [“Blurred Lines”]. It felt like having to talk about it was doing the opposite of what I wanted, was putting myself at the front and centre of this thing that I wanted to be more than. But it’s the thesis of the book. So I’m happy it’s there and I hope it functions as I want it to.

Why do you say it is the thesis of the book?

I think what I’m saying to you about power, and how I wanted to feel and be seen, and think about myself and my position in the world, was I wanted to be this world-famous sexy person. And I wanted to bathe in that identity and the power that came with that. Admitting where I ranked, even on the set of the music video, it takes away that power. And I felt embarrassed of that.

There will be consequences for Robin Thicke.

Yeah. I feel complicated about how the world functions in this black-and-white way, where people are cancelled. I don’t wish that upon anyone and I don’t want that to be what happens. [But] for a long time my existence was about denying my reality, because my reality was inconvenient. We have to change the kind of stories that we allow to be told. I’m no longer going to not tell my experience because I’m afraid of how it might harm other people. Because it’s harmed me, to be not able to do that.

What you describe is shocking and yet the video made you famous; it made your career. None of what has happened to you subsequently would have happened without it. How do you feel about that?

Really icky. But that is the point of the book. To have an awareness of these things. The truth is not simple.

After “Blurred Lines”, in your words, you “signed up to be in movies that I didn’t have any interest in and modelled for brands I thought were lame”. Most actors feel obliged to pretend to have enjoyed their time on a film, even if they think it’s terrible. Most models go along with the fiction that they like the clothes they are paid to wear. At times, this book reads like a letter of resignation from the entertainment industry, and fashion.

I wouldn’t say it’s a resignation letter. It’s more like, if you’ve ever noticed me rolling my eyes in any red carpet video, here’s why. Here’s why I have these feelings. I would like to continue to make things, but I don’t want to make things where I’m a pawn in someone else’s game. I don’t know if that’s going to happen or not but at this point, I don’t care.

Graham Greene said there is a splinter of ice in the heart of a writer. You must observe the world with a cold eye, recording things as they are. You must not spare the feelings of those you write about. Do you think you have that splinter?

I do. I think there’s a part of me that’s always been super-hard on myself and everyone else. And I would say that the flipside of that is that my life has been a lot about making other people comfortable and so maybe that’s why this book is so much the opposite.

I want to ask you about feminism. That’s a word you invoked at the beginning of your career. You said your appearance in the “Blurred Lines” video was a feminist statement. You write in the book about how today feminism, at least the word “feminism”, is as much a slogan on a T-shirt as it a description of the ideas that underpinned the women’s movement. How should we feel about that?

I think we need to be careful about it. I think a lot of really radical ideas in recent years have been discussed on the internet, had these amazing moments of visibility, and then been turned into a slogan. Every political upset becomes a hashtag and a story share and then we go back about our lives. Things stay the same. We understand, for example, what’s brought us to the place that we are in Afghanistan now. But then it’s like a shrugging of our shoulders. I think we should be really afraid of that. There used to be this thing of: education is everything, people need to be aware of what feminism is, what racism is, colonialism, whatever. Now it feels like a lot of people are aware. Definitely not everyone, but a lot. But then there’s this feeling like, well, we’re aware now, so that’s good. But when nothing changes? I don’t think that’s progress.

I think people think it’s enough, and I’m certainly guilty of this myself, to acknowledge the problem by going on social media, writing #saveafghanistan, and feeling that you’ve done your bit. Like posting the hashtag is equivalent to taking action.

I used to really believe that it was very important to be politically outspoken. I’m not saying I don’t believe that now. But I have way changed my attitude to using social media. I’m so tired of the words “outspoken” and “celebrity” and “change.” It’s like a bad spoof. It’s like an SNL skit now. It’s really about making yourself feel good. I think when I was younger and sort of discovering my political ideas, it felt exciting to be able to impact people. Now it feels like I’m trying to award myself.

Writing a book is a bigger commitment than posting a Tweet but there are those who might suggest there’s not much difference in terms of its effect.

I would say the difference is nuance. There’s no nuance in a tweet or a repost. Writing allows for nuance. That’s why I chose this medium. That’s why I wrote the book.

You have 28 million followers on Instagram. That number is so huge that it’s sort of inconceivable. You talk about Instagram in My Body as a measure not only of your allure but of your “lovability”. That sounds extremely unhealthy to me.

Yes, and I think it doesn’t matter if you have 28 million or 28 followers. We look for love and the kind of validation that love can bring through social media.

As someone who has got 28 million followers, rather than 28, does it work?

No. It doesn’t work. I mean, it’s fun to have people say, “Oh my god, I can’t even imagine that number.” But I don’t think it’s a substitute for love.

People are addicted to likes. Posting something and then watching the numbers go up, feeling good if it’s a high number and feeling terrible if it’s not. I’d kind of assumed that once you get to crazy numbers like yours, you wouldn’t even check. But you still do.

For me, the amount I get paid for a post is based on my interactions so it’s not even just about lovability. It’s, “Am I getting enough interactions to keep the value of my posts up so I can have more money?” So, I actually think the stakes get higher.

You still post photographs of yourself in bikinis.

I have a swimwear brand. When I post it’s more intentional and more self-aware, and really always connected to my business. There’s a drive to continue to win, to continue to make money. Rihanna just became a billionaire. It’s interesting to see people who post about how billionaires shouldn’t exist celebrating Rihanna as a billionaire. I definitely don’t think billionaires should exist but also, when am I going to say that I’m done? I’m 30 and now I have my own business that I control. And it’s not somebody else’s images of my body, it’s my own images. And there is still a part of me that feels like it’s a celebration. You have women who choose to completely cover up and women who choose the opposite, but it all feels like a reaction, and I haven’t decided how I feel about that yet.

Your career as a published writer began in earnest with “Buying Myself Back”, in New York. Were you surprised at the reaction?

Shocked. I was terrified. I would say in the week leading up to its publication I was… unwell. As I think I will probably be around the book. I didn’t think anyone was going to have any sympathy or empathy for my position. I didn’t want to impact other people’s lives in any way. I had a lot of thoughts of, “What is wrong with me for wanting to publish this essay?” And what came out of it, the rewarding part, was that there were so many women who had had similar experiences. It validated their truths. And it also started a conversation around image and ownership, which was really important to me.

At Christie’s earlier this year you sold an NFT. It is a digital image of you standing next to another image of you, reproduced on canvas by the artist Richard Prince, that you bought from him for $80,000. The Richard Prince was adapted in turn, and without permission, from yet another image of you, that you had posted on Instagram, of a photo from Sports Illustrated, in which you are shown naked but for some neatly applied bodypaint. The NFT was entitled “Buying Myself Back: A Model for Redistribution.” It went for $175,000. Can you explain a bit about that?

When I was writing “Buying Myself Back” I kept thinking of all these other Emilys that exist, virtually, or on posters or… I mean, people have tattoos of me. I don’t have any control of these images, they just exist in the world, floating around. It’s weird to think about. It’s almost like a nightmare. And when I heard about NFTs, I started thinking about what it would mean as a model, to have the ability, every time an image is sold, to continue to profit off it. And forget the profit, even. The idea that I would have some ownership of the image, and a way of tracing it. I started to think that this could be a way to keep track of all those other Emilys. Using the Richard Prince piece was symbolic for me. I used to think that you put something out and then you have control over it, you were dictating how it was going to be received, and used, and you have ownership. And obviously that’s so not true. And for women it’s really complicated. Revenge porn, for example, has become this huge issue. I was interested in extending the conversation around ownership, and how we can continue to try to control these images of our bodies, and ourselves, and try to have some agency in this world.

Do you think My Body is an angry book?

I definitely have a lot of anger. Part of writing about these things was about connecting to my anger, looking it in the face. Because I hadn’t done that. I was angry but I didn’t really know why.

One of the things that becomes obvious reading the book is that it matters greatly to you that the world takes you seriously.

I wish that I didn’t need that. I do. I think there’s another version of my life, and myself, that wouldn’t give a shit. But I definitely have something to prove. And at least a portion of it is because I wasn’t taken seriously before, and it made me sad. I’ve realised it’s something that’s really important to me.

This book is dedicated to your son. When one day he is old enough to read it, and understand it, what do you hope he will take from it?

I hope that he’ll understand. And I also want him, as a boy — and I obviously don’t know what his sexuality is, but just existing as a male in the world — to be aware of what it’s like to be a female. And to understand how complicated power is when it comes to sex and beauty, with women.

At times in the book you sound desperately unhappy. Has writing it been cathartic, has it helped you?

Yes, writing helped. The process of writing is painful. I wouldn’t say it’s easy or enjoyable but it’s certainly satisfying.

Are you still writing?

I’m not writing right now. I took some time off and I’ve been taking care of my son. But I definitely want to start writing again. I hope that I start before the book is published, but I also hope that the experience of publishing the book encourages me to write more. My plan has always been to write many books. That’s my hope. But we’ll see. I don’t know what this is going to be like.

'My Body' by Emily Ratajkowski (Quercus, £17) is out November 9th