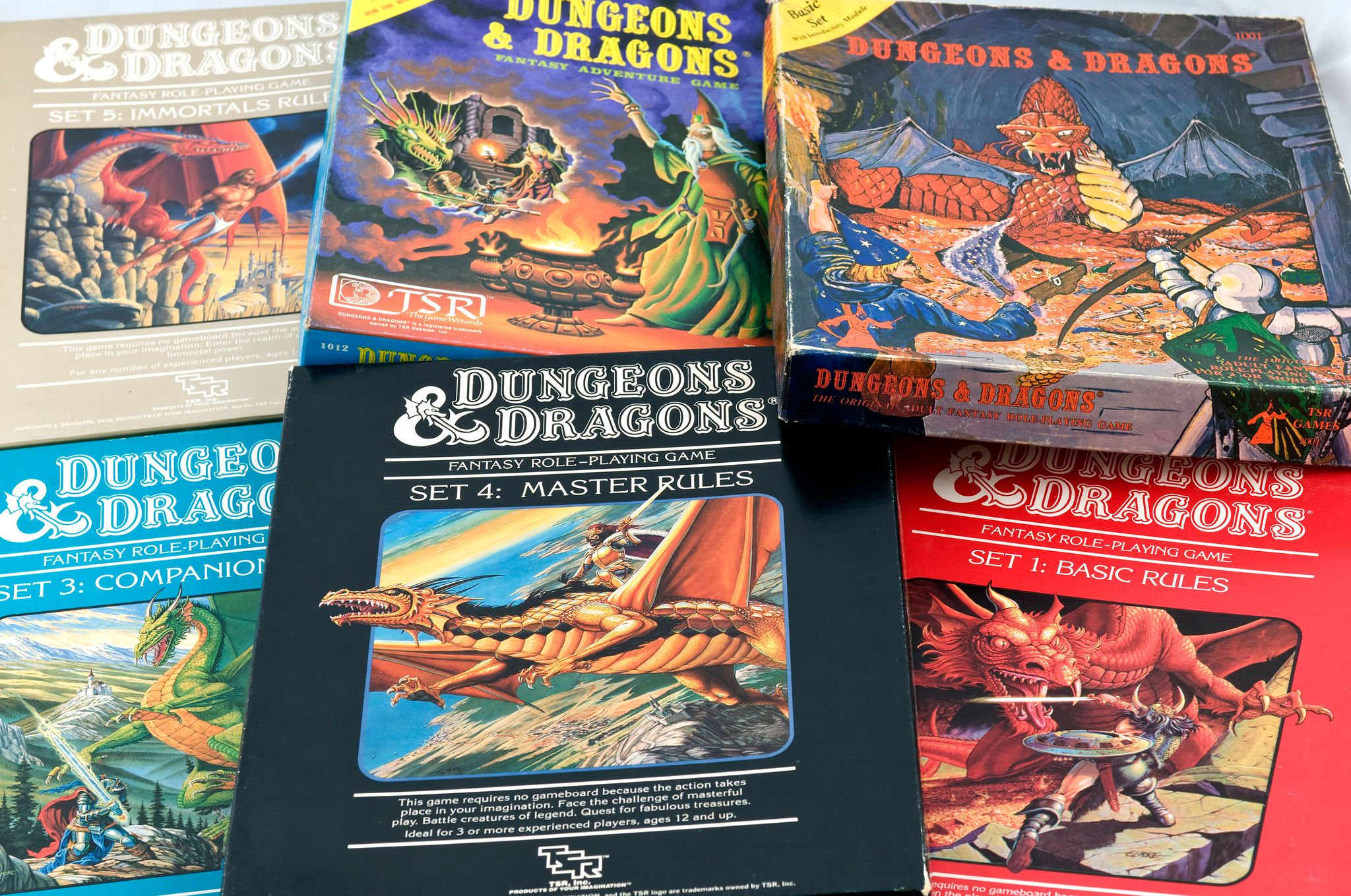

Dungeons & Dragons, the tabletop fantasy roleplay game developed by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson in the American Midwest in the 1970s, is about to celebrate its 50th anniversary. Its popularity has been a slow burn. There was an initial boom, then a blip during the so-called Satanic Panic of the mid-1980s, when D&D, alongside horror movies and heavy-metal records and everything else beloved of teenage boys, was accused of being a precursor to ritualistic murder. But now it’s bigger than ever. (Spookily, or not, the Satanic Panic was itself a precursor — to QAnon. Coincidence?? Wake up, sheeple!)

Sales in D&D paraphernalia — the players’ handbook, starter sets, merch — increased by 30 per cent in 2020, but the game was on the rise already, popularised by Stranger Things, Netflix’s hit show. After series four aired last year, Google searches for “how to play Dungeons and Dragons” rose by 600 per cent. Next week sees the release of Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves, the first official live-action movie, starring Chris Pine. You know, that well-known nerd.

Sadly, none of which, not even Captain Kirk himself, will do anything to lessen the stigma attached to D&D. I should know. I have been a devotee for a few years now, and no matter how progressive society claims to be, no matter how many series of Stranger Things arrive, people will always snigger when I tell them I play. They look at me as if I’ve said I’m marrying a cow. But they don’t understand the pure joy of it. The creativity, the brotherhood, the feeling of fulfilment when you finally vanquish the necromancer.

It was a slow burn for me, too. As a younger man I was aware of D&D, but only in the abstract. Like Texan barbecue or oom-pah music, it was something I knew other people were into, but not anyone I was likely to encounter. Then, a few years ago, an old friend, Jack, told me he had been “running campaigns” (playing D&D) since university, so I asked if I could join his next game. I couldn’t — it doesn’t really work like that, but Jack offered to “DM” (Dungeon Master) a new campaign (game) for me and some of our friends. A few weeks later, our inaugural quest began over crisps and Kronenbourg in his south London kitchen.

Like all good games, Dungeons & Dragons is both simple and rich in nuance. To get the most from it, you need to be dedicated, attentive and perhaps very slightly stoned. Each player has a character which has either been assigned to them or which they have created. It could be an orc with an insatiable bloodlust, or a hoary old wizard, freshly divorced and out on the pull. You could even be a mewling sous-chef, armed only with a ladle, the ability to shower enemies with cooking grease and a need to make your estranged daughter proud: meet “Malcolm Lightfoot”, a character created by my friend Tom, a TV executive in his mid-thirties.

Some characters are fighters, others are thinkers. Some are at one with nature, able to command woodland creatures to their bidding, while others can raze whole forests with the swing of an axe. There are races, classes, attributes, skills, incantations, evocations, Faustian matriculations… Everything you do is down to chance, and every action has a reaction. Essentially, you can do anything, so long as the DM allows you to try and luck is on your side. That luck is tested by the roll of one of seven dice, ranging from four- to 20-sided. Crucially, you can die. If your “hit points” (life) diminish below the requisite level, then you’re out. End of story.

The thrust of the game is the quest, and the DM is its omniscient architect. He or she designs the loose storyline (generally a mission to retrieve, save or discover something), the world in which the story happens and the obstacles met along the way. The DM also plays all the NPCs (non-player characters). King of the nerds? Truly. But that’s what you want: someone deep in the culture who relishes the quest and takes it completely seriously, no matter the ick. And there can be an ick, especially early on. When someone speaks in their character’s voice, for example, it stings cynical ears. But therein lies the magic. If you can get over that cringe, then you are free. You’ve been red-pilled. But instead of waking up next to Larry Fishburne in a burned-out hellscape, you just pretend to be an elf and laugh uncontrollably.

That first campaign lasted well over a year, with the four of us meeting in that kitchen once every couple of weeks. The only real requirement was to be as dumb and funny as possible, and the quest would sort itself out. It was joyous. Not just for the sheer puerile idiocy of it, but because four grown men were able to relish in play in its purest sense. Like we were six years old again.

In the winter lockdowns, I found solace in weekly D&D sessions via Zoom. My day job was, as it remains, to cover fashion and luxury for this magazine. My other hobbies matched those of many other standard-issue thirty-something men, during those days: I ran more; I baked; I rewatched The Wire and tended a meagre garden. But on Wednesdays I would cocoon myself in the back bedroom, arrange my dice and notepad and settle in for a couple of hours of Tolkienian escapism. Nothing beat the ennui of a looming real-world annihilation like a tussle with a gnome.

Our lockdown crew was stringent in the observance of the rules, which only made the campaigns more fulfilling. The interchanging DMs spent hours drawing maps, creating multifaceted NPCs and writing stirring speeches. Our sessions were chapters, rather than get-togethers, and each time we finished there was a feeling of genuine achievement for each of us — four fairly disparate men, linked only by Zoom and a love of Odyssean storylines.

We tore through the campaigns, and as we went along, my characters became much more complex. When they died, as they often did, I felt the loss keenly. Hjelme, a thuggish dragonborn (humanoid dragon, impervious to fire damage) with a chequered past, sacrificed herself to save another member of the team. In the grip of a pandemic, it’s deeply sad when something you’ve channelled the last of your dwindling creativity into gets mauled by goblins.

Having said that, I was recently ousted from my usual gang on the grounds of perceived low attendance. Invited back only as an occasional cameo. Too much time at fashion shows, perhaps. So I am now at something of a loose end. If you hear of any maidens needing rescue from a curse, you know where to find me. And to those who pour scorn, “na’ga rahn fenedhis!”