This article was originally published in the Winter 2022 issue of Esquire.

How do things fit together? How was America made, and how has that history turned into the stories on our screens?

The musical Oklahoma! opened on Broadway on 31 March, 1943. It was an extraordinary, dynamic production, as if to justify its exclamation mark. In a nation at war, the songs by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein spoke to an optimism for the American West — it’s there in the classic opening song, “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’”, and in the choreography by Agnes de Mille. The love story climaxed with the new statehood of Oklahoma in 1907.

But this hit show (over 2,200 first-run performances) was also a travesty of American history. It omitted so much about the state it was admiring. You can’t blame that on Martin Scorsese; he was only four months old when the musical opened, living in lower Manhattan. But now we have caught up on history, and on 17 November he is 80 years old. Congratulations, Marty. But what about Oklahoma?

William King Hale was born in Greenville, Texas, on Christmas Eve, 1874. What has he got to do with this? Will you be patient if I tell you he is Robert De Niro, in his 10th film for Scorsese?

Not much is known about Hale until he found what was then called “Oklahoma Territory”. The name “Oklahoma” derived from the Choctaw language, and it meant “red people”. We needed the word in the second half of the 19th century, because material progress had ordered several Indian nations to be removed from their homeland and gathered in “Indian Territory” next to Oklahoma Territory.

William Hale became a leader in that process. In time, an FBI report on him would say, “His method of building up power and prestige was to put various individuals under obligation to him by means of gifts and favours shown to them. Consequently, he had a tremendous following in the vicinity, composed not only of the riffraff element that had drifted in, but of many good and substantial citizens.”

The matter was more complicated than Oklahoma! cared to explore. By 1859, it had been appreciated that enormous deposits of oil lay beneath the land of Indian Territory. But how could those nations be trusted with their asset, when white Americans believed they were helpless and primitive? William Hale was all for taking charge, and that meant murdering a number of the Osage people and stealing their land. This was the power and the opportunity he defined.

We don’t know for sure how many he killed, working with a nephew, Ernest Burkhart, who had himself married an Osage woman. But the stories were alarming enough to stir up the infant FBI, and a young agent, Tom White, began to investigate. It was in 1929 that Hale was convicted on a murder charge and sent to prison. He was paroled in 1947 and died in Phoenix, Arizona, in 1962.

Burkhart is Leonardo DiCaprio and Tom White is Jesse Plemons. Lily Gladstone (of Blackfoot descent) is Burkhart’s wife, Mollie. The film, Killers of the Flower Moon, based on a book by David Grann, is expected to open at Cannes in the spring of 2023. It will be Marty’s new film, and an exceptional event, even as we observe theatrical movie-going fading away.

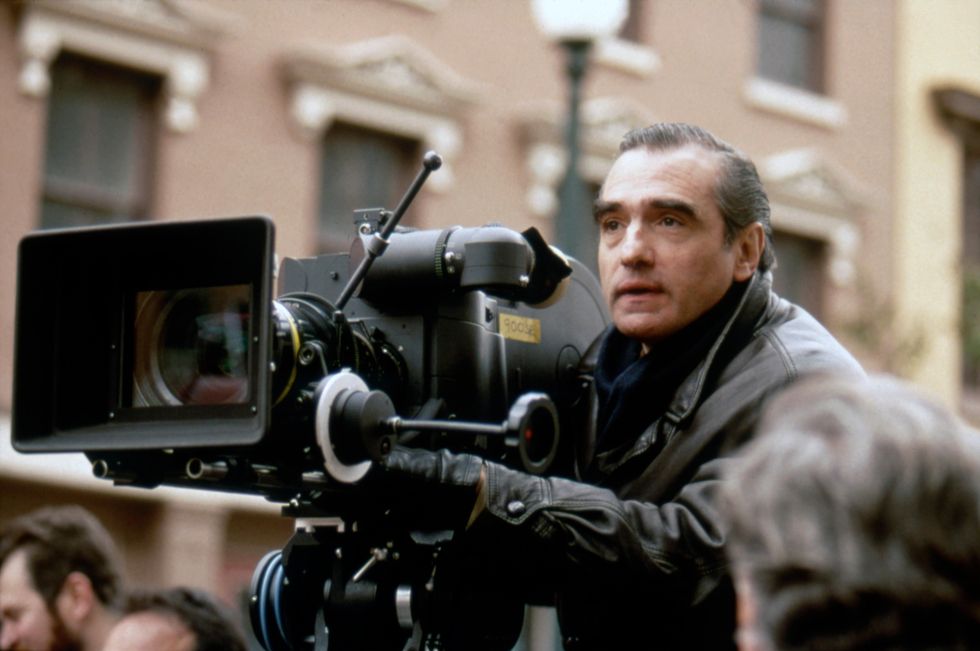

>We have reason to feel fortunate. It is not just that Martin Scorsese is the greatest living American film director, nor even that he has his place in a small pantheon — let it be DW Griffith, Chaplin, Ernst Lubitsch, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock and Walt Disney. You may argue for some others, but you can’t dispute Marty’s place. He would own it on just a few films — Taxi Driver; New York, New York; Raging Bull; Goodfellas; Casino… And others? We’ll come to that.

But there’s another reason for feeling blessed: Marty had been a sickly, asthmatic boy. When he first became famous, with Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976), there were hints in magazine profiles on him that he might not live too long, especially in the cauldron of making movies. As it was, the boy living in Little Italy was not allowed to play sports. Instead, he sat in movie theatres for hours and years. He looked the part: pale, thin and only 5ft 4in. At 80, he’s likely an inch or two shorter.

That’s where the vital contradictions begin: an invalid who is driven by fierce energy and staccato talk; a Catholic who has had five marriages and four divorces (he has three children); the creator of would-be saints who may become monsters — think of Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver — a non-athlete who made boxing feel operatic in Raging Bull; a zealot for creative meticulousness who understood the wipe-out chaos of cocaine in Goodfellas. For decades, from Mean Streets to The Irishman, he rhapsodised over intimidating, passionate gangs, like the fragile kid who observed the “riffraff element” on

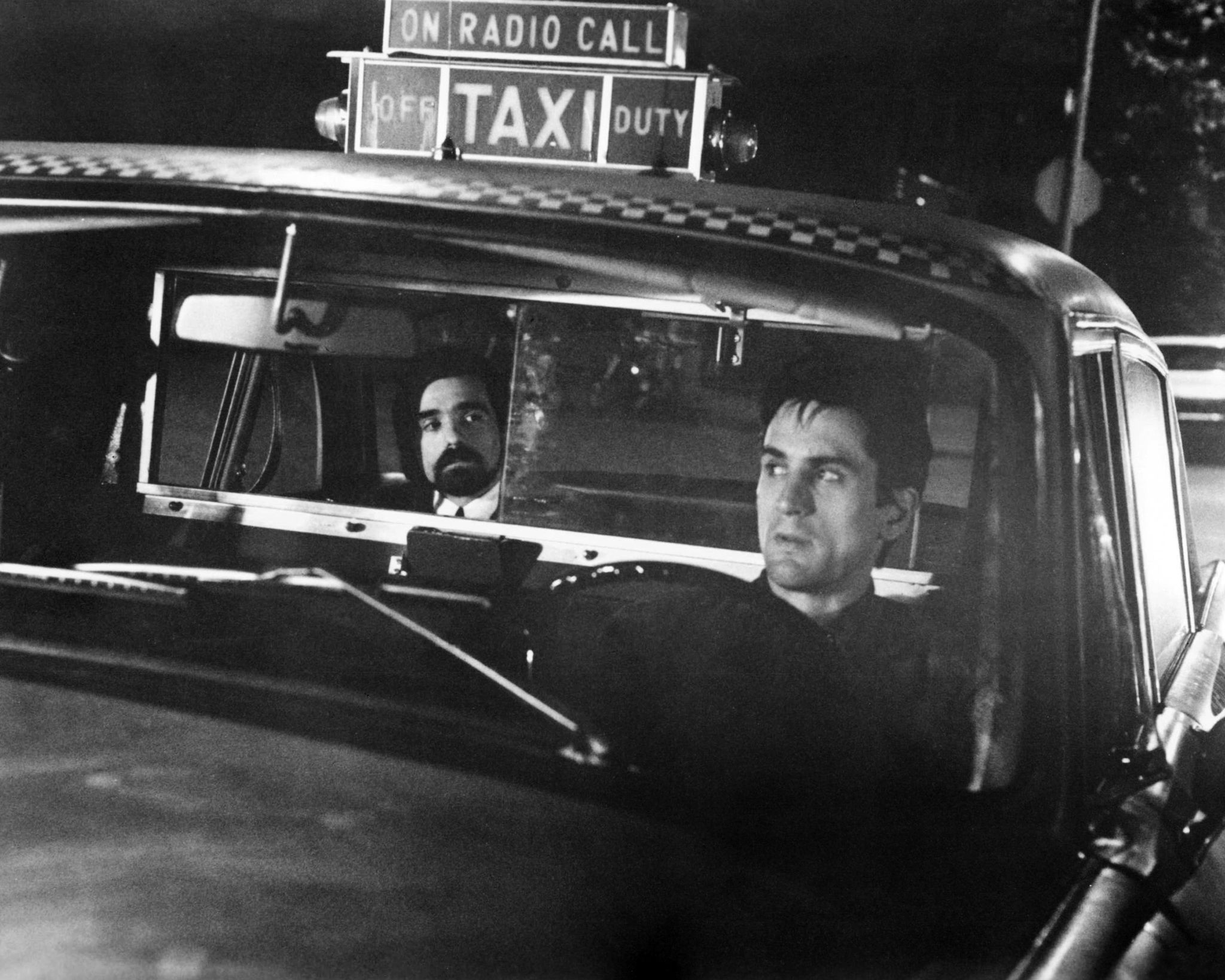

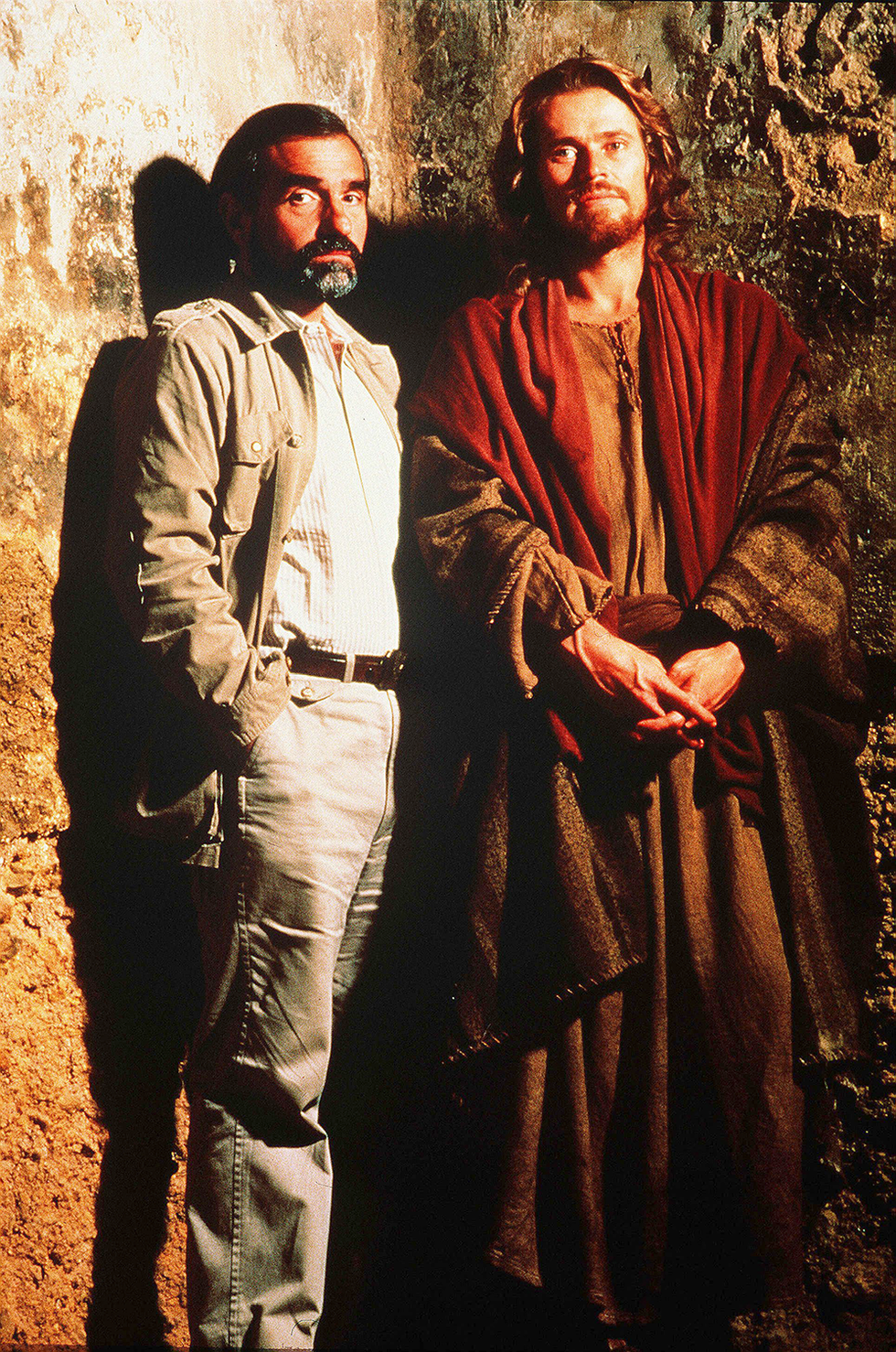

the streets of Little Italy. The lapsed Catholic has made three movies about religious conviction — The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun and Silence. Put it this way: he has shown a yearning to be a good man, but it was Marty who insisted on playing the guy in the back of Travis’s cab, the one who talks about murdering his faithless wife.

Looking up at the apartment window where his wife is seeing another man, this back-seat customer tells Travis he’s going to kill his wife with a .44 Magnum pistol. “Did you ever see what a .44 can do to a woman’s face? Did you ever see what it can do to a woman’s pussy?” And in our own dark we trembled at wondering if we would have to see such things.

I’m not sure a director had ever been so thrilled yet threatening in one of his own films. He wears a black beard in the scene. He seems movie-dangerous, because of the rapt intensity in the way he speaks. But he is still a pale kid at the cinema, like a saint and a devil, violent yet austere. I think those clashing impulses have worried Scorsese all his life.

If you doubt that, just recall how at the end of Taxi Driver, after Travis has embarked on an insane killing spree where the red of the blood had to be toned down for the film to keep an “R” rating, the movie does not bother with cinema’s customary get-out-of-jail-free card by removing the violent outlaw — the way Jimmy Cagney blows himself up in White Heat (1949), or the solution to Bonnie and Clyde (1967), in which the lovely outlaws are shot to shreds.

Instead, Travis is back on the street, a cabbie still, and some grotesque celebrity. That’s how thoroughly Scorsese and his screenwriter Paul Schrader understood America in 1976, the year of the bicentenary. Such drivers are still out there, fuelled by the lurid talk in old movies, the glamorisation of violence, and the Second Amendment’s blithe madness in making lethal weapons available.

You may cry out, “isn’t that taking Taxi Driver too seriously?” Can’t the film be just an exciting séance with death and dread, filmed in emotional colours on the scummy night streets where the yellow of cabs is like a warning of plague? Add in the last movie score that Bernard Herrmann ever wrote (he had done Citizen Kane and Vertigo), and a cast of vivid players from the fever of urban adrenaline. That included Jodie Foster (aged 12), Cybill Shepherd (never better), Harvey Keitel, Peter Boyle and the haunting, flawed outcast of De Niro himself, as a very dangerous man who seeks to rescue Foster’s character from prostitution and some early casual death. And don’t forget Marty in the back seat.

You see, Taxi Driver is so grave a film, so penetrating, that it knew about the meaning of the bicentennial, and it was made by three guys who had no doubt that movies were the highest expression of what America was dreaming and recognised how insane the country was. You can’t give proper credit to Marty without realising how, in his success and his wealth, he feels he lives in a madhouse. So yes, he does films for our fun, and his living, and from his delight in making spectacle happen on camera, but that’s beside the point. He has to do it; he would do it for nothing, in his own head — that’s how he understands Travis Bickle.

So where has Oklahoma gone? Don’t you worry your sweet head. It’s where it’s always been, and it’s waiting for us. Just worry about the chance of an ambush.

In 1976, De Niro, Schrader and Scorsese were a trinity, so that it was hard to discern how the three strands had made the rope of Taxi Driver. The film-makers would have been lost without De Niro, who did some improvs on top of Schrader’s lines, like the “You talkin’ to me?” riff. But there’s so much Schrader in the film — the agonised intensity of being a loner, the spiritual ordeal, the fascination with violence. Scorsese might have felt he was a loner, too, but he wasn’t as isolated as Schrader. Marty was the aspiring onlooker kid who had always wanted to surpass frailty and be part of the gang. This desire may not be fully realised in Taxi Driver, but we feel the attraction of the grim streets in Hermann’s romantic music.

That tension became luminous and lyrical in Raging Bull, in which Jake LaMotta is another outsider, a troubled man who can’t trust anyone, punching his way out of paranoia, but exulting in how a boxing champion can be the centre for a sleazy entourage that manages and screws him. There had been a starter gang in Mean Streets, but it flowers in Raging Bull, where Jake inspires homoerotic awe in characters played by Nicholas Colosanto, Frank Vincent and Joe Pesci, who plays Jake’s brother, his punching bag and loyal second. Pesci had hardly worked on-screen before Raging Bull (he had been a singer and a comic), but Marty saw him and recognised a ticking bomb. Without ever playing a lead, Joe Pesci became a touchstone to Scorsese for 40 years.

You can’t recollect Goodfellas without having Pesci in your head, especially that tense anD much-imitated scene where his character, Tommy, makes a joke to Henry (Ray Liotta) and then begins to hound him — “What do you mean I’m funny?” — until there’s a threat in the stilled air. Tommy will be offed before the end of the film, but not before, on a whim, he has shot the toes off the character played by Michael Imperioli. There’s a lot of menace flashed around on American movie screens, especially in gangster films, but has anyone been more scary than Pesci’s Tommy? He got the Oscar for supporting actor and brought uncanny charm to the idea of the psychopath. You can feel how Marty loved him.

As the title promises, Goodfellas is a genial panorama of lowlife gangs. Calmly, in an academic forum, Marty might have said how much he deplored such hoodlums. But you can’t deny his screen and the ecstasy in which he joins in the social life of mobsters. Just remember the unbroken, headlong tracking shot where Henry takes his girl through the back door of the Copacabana nightclub to greet all his cronies. Marty is getting off on the shot, with The Crystals singing “Then He Kissed Me” in the background — Marty snorts music, it’s the only way to put it. Ray Liotta is the lead and there is terrific work from De Niro and Paul Sorvino, and from Lorraine Bracco and Gina Mastrogiacomo as Henry’s women.

But there’s a way in which Goodfellas gives up the ghost of decency: it’s as if Marty is saying, “Yes, of course these are terrible guys, but I can’t stop wanting to be with them.” The running of old routines became clearer still in Casino, in which De Niro plays a suave gangster, Sam Rothstein, who wants to make Las Vegas function as an efficient business. But he has a friend, a destructive rogue, who insists on screwing up the works. Naturally, this guy, Nicky, is Joe Pesci, in fits of cruel comedy. There is an elegant and sardonic irony in the way Nicky and Sam’s wife Ginger (Sharon Stone, in her greatest work) dismantle all the cool plans.

I rate Casino as one of Scorsese’s best pictures, and the most beautiful (it has an elegiac trashiness). But, as it came out, I felt some frustration, too — how many gang movies did this director need to make? It’s not an impertinent question to ask of so large and ambitious a talent, let alone one who has attempted searching ruminations on virtue, sin and our soul. Great artists want to face ultimate subjects.

Yet sometimes Marty seemed complacent about his dreadful gangs, and this isn’t just Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Goodfellas and Casino. It includes the dazzling recreation of the mid-19th century in Gangs of New York (with Daniel Day-Lewis, as cold and sharp as his character’s knives, playing Bill “the Butcher” Cutting). You should add The Departed, adapted from a Hong Kong movie, Infernal Affairs, a film with twin gangs: the mob and the cops. In the faithful church of Scorsese, The Departed is regarded as a classic that won best picture and best director Oscars (the only wins he’s had), lit up by a smouldering and wicked Jack Nicholson. I demur in that respect: I think it’s a dull, repetitive work, after several gangster pictures too many. It’s a self-admiring film for addicts and those fantasising over gangster routines, with not one challenging character in sight.

You see, I think so highly of Martin Scorsese that I feel a certain duty in calling out his inferior stuff. Along with The Departed, I’d throw in Shutter Island, Cape Fear and The Aviator, all of which are crammed with brilliant action but unable to disguise the inner listlessness of the project. We don’t care about these lurid phantoms. We feel a great director not quite knowing where to go.

Before we get to now or Oklahoma, this is the point to praise Scorsese as the defender and the godfather of adventurous independent film-making. He quickly became the model that film students wanted to emulate, to meet and to show their scripts. And he was patient and understanding with many good causes. He did several fine documentaries on movies and on music: this reaches from The Last Waltz, a concert record of the final show by The Band, to the biopic on George Harrison, Living in the Material World. He spoke up for film preservation, for Technicolor, for remembering the great old films, and lent his support to so many difficult projects. In just the last few years, he has been an executive producer on Pieces of a Woman, the two parts of Joanna Hogg’s Souvenir and Paul Schrader’s The Card Counter.

Those credits don’t necessarily mean a lot of work, but they were a way of saying Scorsese had the films’ back, and that could be instrumental and helpful. There’s kindness in his energy, and the best example of that is the way Marty embraced the English director Michael Powell. He promoted interest in Powell’s great films from the 1940s (like The Red Shoes and I Know Where I’m Going), distributed his cult classic, Peeping Tom, and helped look after Powell in his last days, alongside Powell’s wife, Thelma Schoonmaker, who had been Scorsese’s editor since 1967. Powell and Schoonmaker actually met in the cutting room on Raging Bull.

But then, as he passed 75, there was also a plaintive Marty asking the world, like a kid, couldn’t he get to do a gangster picture like he’d always wanted? He was talking about The Irishman, an epic about how Jimmy Hoffa, the Teamsters’ boss, had been removed by the mob because he was getting out of line. The gang were all there for the film: De Niro, Pesci (in a lovely, fond portrait of old age), Keitel, with the belated arrival of the one obvious actor Scorsese had not worked with yet — Al Pacino, as a very theatrical Hoffa.

The production was the most difficult of all Scorsese pictures. A total budget of $200m was looming. Studios like Paramount reneged on their initial interest and questioned the expense and the value of the CGI process that would allow elderly actors to seem young in flashbacks. At the end of the day, the budget was out of reach for conventional film studios. So Netflix stepped in and said it would take it on. This was a challenging metaphor for the way, even ahead of Covid, the theatrical movie business was foundering.

So The Irishman got done at 209 gradual minutes, and it opened in November 2019, with a brief theatrical window before Netflix set it streaming. How was it? Well, it was not the movie-movie such as Marty was trying to save. It was a confused colossus of new media, in which the de-ageing effects were more distracting than plausible. The Irishman got 10 Oscar nominations, but it won nothing. I think that was because it seemed slow, mournful and distended, like old fellas talking about their inglorious past. You felt you’d seen it too many times already. Until the closing passages.

De Niro plays Frank Sheeran, a man who has been a gangster all his life, part of the plot to kill Hoffa, and a career liar to his own family. All of a sudden, at its close, the film picks up its head and its heart as Sheeran’s daughter Peggy (Anna Paquin) comes to recognise the lifelong dishonesty of her father and can no longer honour him. This may seem modest as a plot development, but it amounts to a fringe member in the gang saying, “No, this cannot pass; it will not be endured.” And it’s piercing.

The ending of The Irishman has a depth of character and an urge to recognise the tragedy that was there in Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, and which inspired the account of marriage in the neglected New York, New York, the story of a guy, Jimmy Doyle (De Niro), who wins Francine (Liza Minnelli) in a frenzied wooing campaign and then turns into a pathological loner who cannot stand to be with anyone. That film was made in high crisis: Scorsese was doing a lot of drugs and he was in turbulent love with Minnelli. It is one of his few films that concentrates on the challenge in a man and a woman trying to be together. Five marriages.

That strained mood returned at the end of The Irishman. The great director was once more engaged with ordinary emotional reality that left no room for hiding behind the deadly glamour of being a guy in a gang.

That makes me hopeful, and now we are in Oklahoma at last. I have not seen Killers of the Flower Moon. I’m sure as I write that its destiny is being determined in the cutting room as Scorsese and Schoonmaker bring it to life, with music by Robbie Robertson. But it is not simply another New York gangster story. Indeed, it has to be a Western if it is set in Oklahoma a hundred years ago, and much of it was filmed in Osage County. How will De Niro look as William Hale? It seems as if it is going to cost $200m again — and that is a budgetary level that should bring no comfort to the man who made Taxi Driver for $1.9m (or about $10m in today’s money).

But if this is another study in how gang terror works, it must also be a story about the larger America, and how the mythology of the West, the spaciousness and the hope, was turned into an oil tract in which many indigenous Americans were not just murdered and deprived of their sacred homeland. They were made part of the ruthless spoiling of the land and its nature in a process that has resonated at last by 2022 and 2023. And this film has a key novelty in Scorsese’s work: one leading character (Jesse Plemons) is an officer of the law, a detective, and a moral observer.

I am sure the 80-year-old will deliver many sequences in which action fills the screen in a flood of cinematic beauty, like water or oil bursting out of the ground. I am also hoping that, at last, Martin Scorsese has done a picture that tells us, “Look, see and grasp racism, greed, overbearing maleness and betrayal — that is how we got where we are.” A great director may be about to deliver a great work as our birthday present.