There are many things Gareth Southgate is. An unexpectedly decent manager of the England men’s football team; a considered, measured thinker; a setter of unlikely menswear trends. One thing he is not — at least not yet — is a Shakespearean hero (or, given the fickle nature of the business he’s in, a Shakespearean villain). This was one of the first conundrums with which James Graham, a writer of celebrated works for stage and screen, was faced when he decided to make Southgate the central figure in his new play, Dear England, which premieres in June.

“Gareth is a gentle, thoughtful, quiet, shy person, who is doing something extraordinary,” says Graham, 40, who has cycled from his home in south London to join me in a small, stuffy meeting room in the National Theatre’s iconic concrete complex, where the play will open in the 1,100-capacity Olivier space. “But what he’s doing is really delicate, and how he’s doing it is very internal; a lot of it is in his head and in his heart. That’s definitely the challenge: how you translate that into a very epic space, where we’re used to Shakespearean kings standing there and bellowing out speeches with sword raised. Theatre can do anything, but how do you make Southgate an Olivier star?”

The idea for making a play about Southgate’s surprising rise came to Graham five years ago, as he was following the progress of the England team at the 2018 World Cup. True, England didn’t win, and were eventually sent home from Russia in the semi-finals, but this time their tournament trajectory had a crucial difference, and Graham — whose most recent works include the lauded BBC crime drama Sherwood and the musical Tammy Faye, co-written with Elton John, about televangelist and gay icon Tammy Faye Bakker — saw the narrative potential.

“The main thing about 2018 was that they beat Colombia on penalties, so it was breaking the curse of English football, and it being Southgate who did it,” says Graham, who describes himself as a casual fan of the sport, though not one who follows it at club level. “I went, ‘There’s at least one thing to connect dramatically.’”

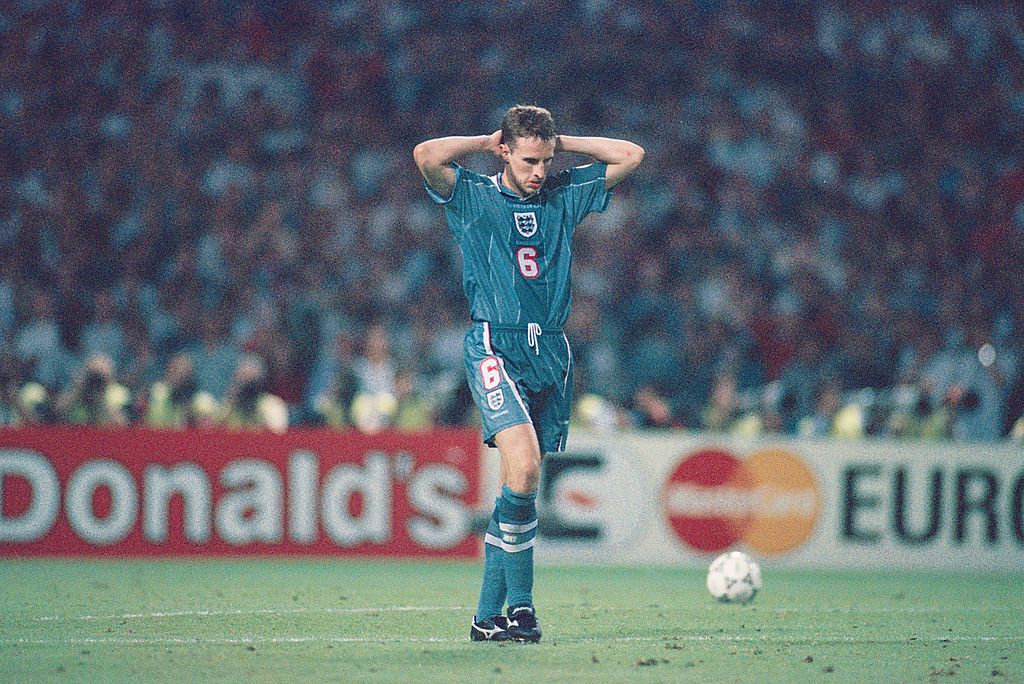

Nearly three decades earlier, Graham remembers watching, on a small TV in the dining hall of Ashfield Comprehensive School in Nottinghamshire, where he’d just come off stage from playing Curley in a school production of Of Mice and Men, the moment that would overshadow much of Southgate’s playing career: his infamous, decisive miss in the penalty shootout against Germany in the semi-final of the 1996 European Championship. “There are those national moments when you feel millions of eyes watching the same thing, and you do feel history writing itself in real time,” he says. “I remember it vividly: the grey of the uniform, and his hands on his neck… Obviously it’s painful for him, but his origin story is a bit of a gift for a writer.”

Fired up, Graham made what he gnomically describes as “tentative contact with certain people in English football” to discuss the possibility of putting Southgate’s story on stage. It wasn’t the first time he’d written about the machinations of institutional power: his breakthrough play, This House, which debuted at the National in 2012, considered the backstage dealings of whips in the House of Commons; his Channel 4 film, Brexit: The Uncivil War, gave us Benedict Cumberbatch as latter-day Machiavel Dominic Cummings; in his play Ink, he explored the birth of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire (Rupert saw it twice). But the response he received from the England camp was surprising.

“I said, ‘I think this is an amazing play,’ and they said, ‘You’re too early. We see this as a three-act structure,’” Graham recalls. As those certain-people-in-English-football saw it, Act III would be the upcoming 2022 World Cup in Qatar. Though he was disappointed, Graham was also impressed that they had their own sense of narrative arc. “And I think a lot of that comes from Gareth,” he says. “One of his many little revolutions was expectation management. They actually had a clock in the training camp ticking down to the Qatar World Cup final for six, seven years, as a long-term plan. So they were like, ‘We probably won’t win the next one. We’re aiming to win Qatar in three tournaments’ time. That’s the end of your play.’ They told me the end of my play. And I waited.”

One thing you could do to make Southgate an Olivier star is book an actual Olivier star to play him. When we meet, Dear England has an impressive creative team in place, including director Rupert Goold, set designs by Es Devlin, and a star-signing: in something of an inspired casting move, the lead role in Dear England (the play’s title is taken from an open letter that Southgate published before the 2021 Euros in which he urged the nation to treat their team with decency and empathy and which, to be fair, was written with a certain John of Gaunt panache) is being filled by Shakespeare in Love star and swoony thesp royalty, Joseph Fiennes.

“For whatever reason, every time I thought about it, I thought, ‘There’s something that feels really right,’” says Graham. “People think of him as this great classical actor who plays big parts, and they’ve been amused, or satisfied, by the idea of him doing it. But then there’s a bit of you that imagines when his agent said, ‘The National have called!’ And he went, ‘Oh good.’ ‘It’s for Gareth Southgate.’ He must have gone, ‘I was expecting Richard III… But sure.’”

At the time we’re talking, the rest of the cast and characters have yet to be announced, in part because Graham hasn’t quite decided how many characters there will be; he often fine-tunes his scripts in the rehearsal room. But there will, he assures, be some representation of the current England squad (“all the Harrys, they’ll be around”) as well as some of Southgate’s team-mates from Euro ’96, who included Alan Shearer and Paul Gascoigne: “I know! Rich pickings for fascinating, complicated men,” he says (feel free to insert a Shearer joke of your own choosing here).

He’s not sure how much actual football will be in it — he’s aware of the potential pitfalls of “a bunch of actors trying to kick a ball on stage” — but this suits him fine. Graham’s work has always been more interested in the behind-the-scenes goings-on within the organisations and entities that shape our public life — the corridors, offices and dressing rooms of power — and about placing those intrigues in a broader social and political context. “It’s about how you use institutions as a microcosm for something bigger

about our national identity,” he says. “The English football team feels perfectly formed to become a metaphor for Englishness, and for the health of the nation, psychologically or otherwise.”

With the current team, he thinks, there are signs that we’re entering remission. Yes, the players’ “larky YouTube videos” or Bukayo Saka’s TikTok spelling bees are charming, but more fundamentally, he points to the measured and mature way in which Saka, Marcus Rashford and Jadon Sancho responded to the racist abuse they received following their own penalty misses in Russia in 2018, when the ugliest side of English football hooliganism seemed to rise again (encapsulated by the once-seen-never-forgotten photograph of a man bent over with a lit firework up his bum — “I wondered about putting that on the poster, but then I thought you probably do want to sell some tickets,” Graham says).

Does that considered, thoughtful attitude come from Southgate? “As the writer I have to believe that,” says Graham. “But I think his niceness can be overplayed, and I need to be aware of that myself — I have to protect the play a bit — and niceness doesn’t mean he lacks passion. When he’s on the sideline with his fist raised to the sky, screaming in euphoria or agony, there is a fire there, which is helpful.”

Perhaps, Graham reflects, there is something Bard-worthy about Southgate after all. “Shakespearean protagonists have huge objectives: they want to be King of Scotland; they want to find love; they want to be the richest, most powerful people. What he’s doing on a personal level, but also national, is Shakespearean: he’s trying to retrieve the Grail and bring it back, and in doing so fix a wound, I think, in the national soul. If he can fix these men, he could fix all Englishmen. But he has to start with these 11 boys.”

Is there a darkness to the England manager too, then? A tragic flaw? Graham, not wanting to be drawn yet, says he’s “on a journey to understanding that”. As for whether or not Southgate delivered the third act he was hoping for in Qatar — when, in the 84th minute of the quarter-final against France, England captain Harry Kane failed to convert his second penalty of the match, resulting in a humdrum 2-1 defeat — Graham confesses that he was, at the time, a bit confused.

“I had just naively thought, ‘Whatever happens it must mean something, and we’ll make sense of it, and then we’ll make it either funny or tragic or happy,’” he says. “I will admit, going out in the quarter finals, I did go, ‘I don’t know what that means. I don’t feel that’s the explosive ending that I’ve been waiting for, for four years.’”

But gradually, his expectation management kicked in, and the subtler narrative began to emerge. Perhaps, at least for his play’s purposes if not the nation’s, those certain-people-in-English-football were right. “As well as being very upset as a fan,” he says, “I started to realise that of course there’s something inherently more satisfying and painful about the dream not being realised.” ○

“Dear England” runs from 13 June to 11 August, at the National Theatre, London SE1; nationaltheatre.org.uk

Miranda Collinge is the Deputy Editor of Esquire, overseeing editorial commissioning for the brand. With a background in arts and entertainment journalism, she also writes widely herself, on topics ranging from Instagram fish to psychedelic supper clubs, and has written numerous cover profiles for the magazine including Cillian Murphy, Rami Malek and Tom Hardy.