When Jared Harris visited the suite at the Savoy which his father, Richard, had called home for over 20 years, something was off. “I was so disappointed,” Jared says, “I wanted it to be exactly the same.” Since his dad’s death in 2002, the living quarters had been switched around, making the rooms appear smaller. “It’s strange how they managed to pull that off.” The suite, however, is now named after his father. You can stay in it for £2,950 a night. And a portrait of Richard still hangs on the wall, though, as Jared notes, with a wry smile: “It looks like Rod Stewart.”

We are discussing fathers, not only as Jared’s happens to be the legendary Irish actor who portrayed both King Arthur in Camelot and Albus Dumbledore in the first two Harry Potter films, but also because he is taking on the role of a monstrous one in Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming. Directed by Matthew Dunster, the Young Vic production follows professor Teddy (played by Robert Emms) as he returns from America with his wife, Ruth (Lisa Diveney), to London and to his fractious family, which includes his pimp brother Lenny (Joe Cole) and their domineering father Max, whom Harris will play.

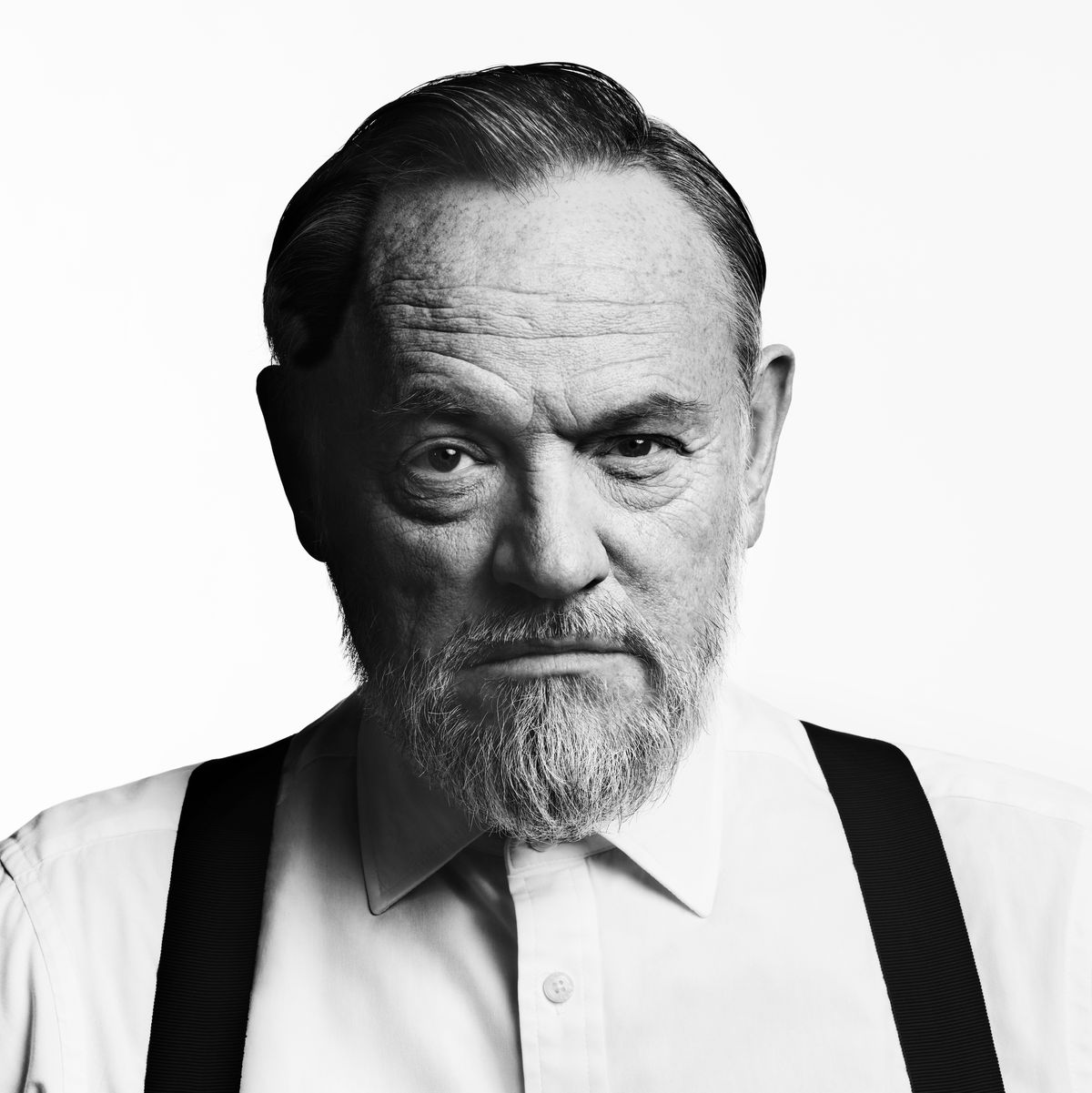

With its ever-shifting sexual and power dynamics, The Homecoming will likely be as disconcerting in 2023 as it was in 1964 when Pinter wrote it. How will audiences react? “Sometimes you laugh because you’re so anxious and you feel relief from it but at the same time, it’s like, ‘Should I be laughing at that?’,” Harris, 62, tells me at the theatre’s bar, a week before previews begin. “If you question yourself all the time, and what your reactions are, that’s a really good thing.”

It has been fifteen years since Harris was last on a London stage, in a production of Tennessee Williams’ A Period of Adjustment at the Almeida (“not known for his comedy,” Harris points out, “it was a bit of struggle in the beginning, but the last 40 minutes every night killed”). In those years, Harris has risen to prominence in a trio of prestige television roles: as tortured financial officer Lane Pryce on Mad Men, heroic scientist Valery Legasov on Chernobyl, and King George VI on the first season of The Crown. Awards followed, including a Bafta for Chernobyl. If you need a not-quite-lead who would steal the show, Harris is the man for the job. “Supporting characters have proper fun because no one is concerned whether an audience will like that character. You’re not carrying the story, so you get to play much more extreme versions of characters,” he says. “What I’ve found is when you’re trying to switch over to main characters, you’re constantly trying to encourage storytellers to be braver about the size of the risks they can take.”

Dunster was receptive to Harris’ thoughts about Max, a desperate man who is losing control of his sons and himself. “Right from the beginning, he redrew the character,” the director tells me over email. “We want these patriarchal characters to be more complex and Jared, in this play and like he does in everything else, is drawn to complexity and layers. If someone just shouts at everyone and is this sort of nasty parental bully then it’s very easy to dismiss this character so he stops being complex and the play stops being complex; Jared’s constantly redrawing our expectations of the man and the world.”

Jared was born in London and is one of three sons: older brother Damian is a director, younger brother Jamie is an actor. Their mother, Elizabeth Rees-Williams, was an actress and the only daughter of Baron Ogmore. Rees-Williams and Richard divorced in 1969, and she married three more times: to actor Rex Harrison, stockbroker Peter Aitken, and finally to Tory MP (and Peter’s cousin), Jonathan Aitken. Richard, labelled a hellraiser, went onto marry actress Ann Turkel, though they later divorced. Still, Jared notes that his father believed that even though “the marriages were failures, the relationships could survive” and it helped that he “very publicly stated that it was his fault”.

Jared himself has been married three times and divorced twice: to Jacqueline Goldenberg and actress Emilia Fox. This summer, he celebrated his 10th wedding anniversary to television host Allegra Riggio. Do any of Jared’s experiences of family life inform his performance in this family drama? “It reminds me of some rows that we had at Christmas,” he says. “There’s that competitiveness when you bring a new partner into the group or family. There’s a lot of anxiety on everyone’s part, trying to make a good impression.”

After attending prep school in East Sussex and later Catholic boarding school Downside near Bath, he crossed the Atlantic to study at Duke University in North Carolina: “I was feeling stifled so I went someplace where nobody knew me and I could find out who I was by seeing how people responded to you.” How did people respond to him? “I was a weirdo.” In a college full of preppy students, decked out in Lacoste sweaters, Harris would walk around campus with mismatching shoes. “They were all trying to be at a big pre-med, engineering or law school, no interest in the arts whatsoever,” he recalls. But Harris fell in with the theatre kids and found his groove: “I enjoyed reading, studying, researching something for the first time.”

Back in London, he attended the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama before enjoying what he describes as “a very good run in independent New York cinema during a golden era of New York independent cinema.” After a disillusioning stint in Los Angeles, in which he auditioned for three serial killers in two weeks – one computer-generated, one a ghost, and one an actual mass-murderer – he returned to New York, where he decided to “find a really cheap apartment and do off Broadway theatre and independent cinema”. When those films became harder to finance, he tried his luck in Los Angeles again. It was Harris’ turn as Captain Mike in 2008’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button which caught the attention of a Mad Men casting director. Harris was only supposed to appear in one episode; the show’s creator, Matthew Weiner, liked him so much, he stayed for two seasons.

Whatever you might expect from a child of Hollywood royalty and English aristocracy, Harris is not that. He is a warm and curious conversationalist, happy to discuss Ru Paul’s Drag Race (which he loves) and reality show Survivor (“even though it takes place on a desert island, it’s really about corporate politics”). He is also willing to put up with some rather inelegant questions on my part like, does performing in The Homecoming in London also feel like a homecoming? It’s complicated, he says, given his nomadic family life. “My mother always wanted to be the one who would supply us with a home, but she had wanderlust.” She would find properties, do them up and move on every few years, Harris explains. “Dad, of course, was a gypsy until he bought the house in the Bahamas, and it used to drive my mother crazy, that that became our home. We had that for 28 years.”

Does a lifetime of talking about his father ever become tiring? “I love talking about him,” Jared says. “I miss him, and I love meeting people who will tell me something about him I’ve never heard before.” In a typically generous way, he provides me with a story of his own. One Sunday, he went to meet Richard at The Wellington, a pub around the corner from the Savoy. It was the summer, so they sat outside. “An Irish guy stops by and says hello, and dad is usually very friendly and chats to people, but he gave the cold shoulder to this guy,” Jared says. So what was wrong with this particular Irishman? “Dad said, ‘You don’t want him hanging about: he’s the gravedigger from Limerick.” That turned out to be the very last pint Jared had with his father: within a month, Richard was in hospital, and he died in the autumn. “If you wrote that in a story,” Jared says, “someone would say it’s unbelievable.”

‘The Homecoming’ is on at the Young Vic until January 27

Henry Wong is a senior culture writer at Esquire, working across digital and print. He covers film, television, books, and art for the magazine, and also writes profiles.