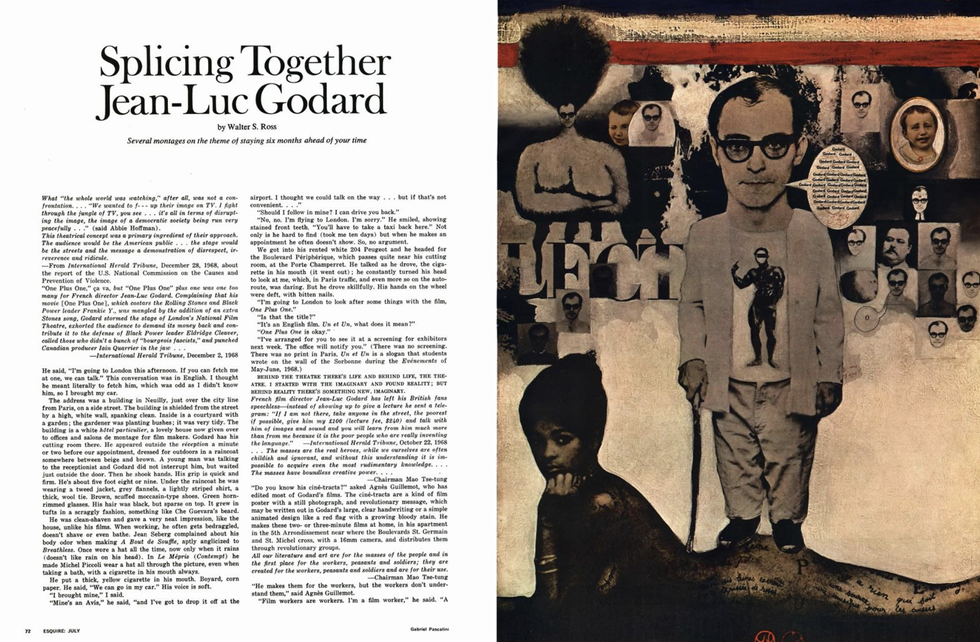

This article originally appeared in the July 1969 issue of Esquire US. To read every Esquire US story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

What “the whole world was watching,” after all, was not a confrontation. . . . “We wanted to f--- up their image on TV. I fight through the jungle of TV, you see . . . it’s all in terms of disrupting the image, the image of a democratic society being run very peacefully . . .” (said Abbie Hoffman).

This theatrical concept was a primary ingredient of their approach. The audience would be the American public . . . the stage would be the streets and the message a demonstration of disrespect, irreverence and ridicule. —From International Herald Tribune, December 28, 1968, about the report of the U.S. National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence.

“One Plus One,” ça va, but “One Plus One” plus one was one too many for French director Jean-Luc Godard. Complaining that his movie [One Plus One], which costars the Rolling Stones and Black Power leader Frankie Y., was mangled by the addition of an extra Stones song, Godard stormed the stage of London’s National Film Theatre, exhorted the audience to demand its money back and contribute it to the defense of Black Power leader Eldridge Cleaver, called those who didn’t a bunch of “bourgeois fascists,” and punched Canadian producer Iain Quarrier in the jaw . . . —International Herald Tribune, December 2, 1968

He said, “I’m going to London this afternoon. If you can fetch me at one, we can talk.” This conversation was in English. I thought he meant literally to fetch him, which was odd as I didn’t know him, so I brought my car.

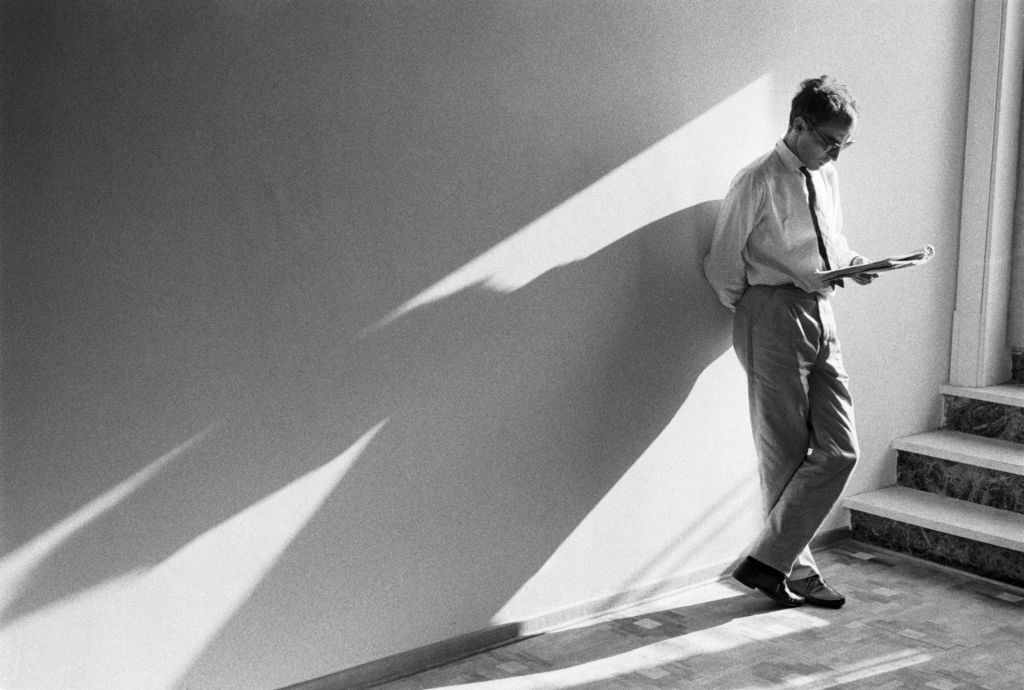

The address was a building in Neuilly, just over the city line from Paris, on a side street. The building is shielded from the street by a high, white wall, spanking clean. Inside is a courtyard with a garden; the gardener was planting bushes; it was very tidy. The building is a white hôtel particulier, a lovely house now given over to offices and salons de montage for film makers. Godard has his cutting room there. He appeared outside the réception a minute or two before our appointment, dressed for outdoors in a raincoat somewhere between beige and brown. A young man was talking to the receptionist and Godard did not interrupt him, but waited just outside the door. Then he shook hands. His grip is quick and firm. He’s about five foot eight or nine. Under the raincoat he was wearing a tweed jacket, grey flannels, a lightly striped shirt, a thick, wool tie. Brown, scuffed moccasin-type shoes. Green horn-rimmed glasses. His hair was black, but sparse on top. It grew in tufts in a scraggly fashion, something like Che Guevara’s beard.

He was clean-shaven and gave a very neat impression, like the house, unlike his films. When working, he often gets bedraggled, doesn’t shave or even bathe. Jean Seberg complained about his body odor when making A Bout de Souffle, aptly anglicized to Breathless. Once wore a hat all the time, now only when it rains (doesn’t like rain on his head). In Le Mépris (Contempt) he made Michel Piccoli wear a hat all through the picture, even when taking a bath, with a cigarette in his mouth always.

He put a thick, yellow cigarette in his mouth. Boyard, corn paper. He said, “We can go in my car.” His voice is soft.

“I brought mine,” I said.

“Mine’s an Avis,” he said, “and I’ve got to drop it off at the airport. I thought we could talk on the way . . . but if that’s not convenient. . . .”

“Should I follow in mine? I can drive you back.”

“No, no. I’m flying to London. I’m sorry.” He smiled, showing stained front teeth. “You’ll have to take a taxi back here.” Not only is he hard to find (took me ten days) but when he makes an appointment he often doesn’t show. So, no argument.

We got into his rented white 204 Peugeot and he headed for the Boulevard Périphérique, which passes quite near his cutting room, at the Porte Champerret. He talked as he drove, the cigarette in his mouth (it went out); he constantly turned his head to look at me, which, in Paris traffic, and even more so on the autoroute, was daring. But he drove skillfully. His hands on the wheel were deft, with bitten nails.

“I’m going to London to look after some things with the film, One Plus One.”

“Is that the title?”

“It’s an English film. Un et Un, what does it mean?”

“One Plus One is okay.”

“I’ve arranged for you to see it at a screening for exhibitors next week. The office will notify you.” (There was no screening. There was no print in Paris. Un et Un is a slogan that students wrote on the wall of the Sorbonne during the Evénements of May–June, 1968.)

BEHIND THE THEATRE THERE’S LIFE AND BEHIND LIFE, THE THEATRE. I STARTED WITH THE IMAGINARY AND FOUND REALITY; BUT BEHIND REALITY THERE’S SOMETHING NEW, IMAGINARY.

French film director Jean-Luc Godard has left his British fans speechless—instead of showing up to give a lecture he sent a telegram: “If I am not there, take anyone in the street, the poorest if possible, give him my £100 (lecture fee, $200) and talk with him of images and sound and you will learn from him much more than from me because it is the poor people who are really inventing the language.” —International Herald Tribune, October 22, 1968

. . . The masses are the real heroes, while we ourselves are often childish and ignorant, and without this understanding it is impossible to acquire even the most rudimentary knowledge. . . . The masses have boundless creative power. . . . —Chairman Mao Tse-tung

“Do you know his ciné-tracts?” asked Agnès Guillemot, who has edited most of Godard’s films. The ciné-tracts are a kind of film poster with a still photograph, and revolutionary message, which may be written out in Godard’s large, clear handwriting or a simple animated design like a red flag with a growing bloody stain. He makes these two- or three-minute films at home, in his apartment in the 5th Arrondissement near where the Boulevards St. Germain and St. Michel cross, with a 16mm camera, and distributes them through revolutionary groups.

All our literature and art are for the masses of the people and in the first place for the workers, peasants and soldiers; they are created for the workers, peasants and soldiers and are for their use. —Chairman Mao Tse-tung

“He makes them for the workers, but the workers don’t understand them,” said Agnès Guillemot.

“Film workers are workers. I’m a film worker,” he said. “A mechanic. A bonhomme like the others. But I wasn’t brought up a proletarian.”

THE NEW WAVE WOULD LIKE TO MAKE BIG-BUDGET PICTURES.

“Did you say that?”

“Yes, and it’s still true. But the only way they can do it is to make Hollywood movies.”

“Do you keep in touch with Truffaut and Chabrol and the others?”

“No, we don’t see each other much anymore. They’re going in their direction, I’m following my . . . my path. My road. I wouldn’t say avant-garde, who is ahead and behind, just different direction. There’s nothing in common. I am trying to learn how to make a film, my own film, and nobody can teach me.”

We all put ourselves in our films, but Godard exposes more of himself than any of us. —François Truffaut

“If you practice some sort of art it’s because you want to avoid thinking. My films are there, that’s all. There is no art, no results, just something going on. If it isn’t any good, we’ll make another next week. We have to do some things wrong. Let’s destroy some old things to make room for new things.”

A bureaucrat with a taste for celluloid . . . a pretentious canary . . . an unrepentant spoiler of film . . . a press agent for himself. —Positif

A parlor nihilist. —L’Humanité

. . . broken down the barriers between the documentary and the feature, with a showy style and clever panache. —Tony Richardson

MY AESTHETIC IS THE AESTHETIC OF THE SNIPER ON THE ROOF.

“Do you make films for the audience or an audience?”

“For the audience, of course.”

“What audience?”

“The right audience.”

I NEVER THINK OF THE AUDIENCE. I THINK OF THE PICTURE. I DON’T CARE ABOUT THE AUDIENCE, IF IT WILL BE LARGE OR BIG OR SMALL. I MEAN, I CONSIDER MYSELF WHEN I’M EDITING IT. I CONSIDER MYSELF AS THE FIRST SPECTATOR. (He told this to a group of New York University film students in April, 1968.) CONTRADICTION IS THE WORD THAT APPEARS MAINLY IN MAO TSE-TUNG THEORY. HE ALWAYS SAID THINGS ARE WORKING OUT BY CONTRADICTION.

Jean-Luc Godard was born in Paris, December 3, 1930, of Swiss parents. There were four children in the family. His father is a doctor with his own clinic. Jean-Luc was brought up in Geneva and in more provincial Vaud. His parents were divorced. His mother’s family is very rich, a banking family named Monod. His grandfather was head of the Swiss banking corporation called Banque de Paris et des Pays Bas. Godard was brought up a Protestant. He went to school in Nyon, Switzerland. He became a naturalized Swiss during World War II and retains the passport. He went to the Lycée Buffon, Paris, and the Sorbonne, where he took a Certificat in Ethnology in 1949. But he wasn’t going to classes, he was going to the movies. He hung around the Cinéma Club. He met Erich Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, now film directors. Rivette estimated that they saw about a thousand films a year, some days three or four, not counting repeats. In 1950 Godard made a movie of himself and three other people, the four of them sitting around a table for forty minutes and saying nothing. Godard financed it.

Godard’s father stopped sending him money because he wasn’t studying. Godard began writing articles for the monthly La Gazette du Cinéma, which he founded with Rivette and Rohmer, under the name of Hans Lucas (Jean-Luc in German) and stealing. Screenwriter Paul Gégauff caught Godard taking 500 francs out of his (Gégauff’s) jacket. He says Godard helped hoodlums break into the clinic Godard’s father owned. Godard is said to have sold his grandfather’s first editions to get money for movie tickets. He is supposed to have spent eight days in a Swiss jail for stealing from the open safe of a radio company.

He ran away to America for a year or so around 1951, but never talked about it, only sent some postcards.

“In 1953 I was hanging around cafés in Paris wasting my time, writing articles here and there. . . . I had to make money and invest it in something worthwhile. So I left and got a job with the crew building the Grande Dixence Dam in Switzerland.

“At Grande Dixence there was nothing to spend money on. I put aside more than $2000, and on my days off I began to do a documentary film on concrete. I remembered someone having told me: ‘Shoot documentaries. When you know how to film mountains, you will know how to film men.’ I did the sound all by myself. Every weekend I went to a cutting room in Geneva. I did the splicing by hand, scraping the emulsion with a razor blade. I hoped to sell the picture and make enough to live for a year or two in Paris without doing anything—that is, while preparing a feature picture. I had made up my mind to find a way out, and found the will to do it.”

The short he made was called Opération Béton (Operation Concrete), an ordinary documentary by all accounts. It did not earn him much money. He made four more shorts, ranging in length from ten to twenty-one minutes, up until 1959. The style was becoming more adventurous. Tous les Garçons S’appellent Patrick (All Boys Are Called Patrick) and Une Histoire d’Eau (A Story of Water) are well remembered. None has been released commercially in the U. S. Godard also began writing for a Paris art weekly, and did a gossip column for a newspaper, taking literary quotations and attributing them to starlets. At one point he was so broke he slept on a bench in the office.

His mother was killed in a motor-scooter accident in 1954. He was very fond of his mother.

When Claude Chabrol gave up his press agent’s job at Twentieth Century-Fox (Paris) to make films, he arranged for it to go to Godard. A French movie producer Georges de Beauregard showed a film he’d made in Africa to Fox executives, hoping to sell it. He’d had some flops and needed money. When the lights came up Godard arose in the audience, impressed, needing a shave, and said, “This picture stinks.”

“After that beautiful beginning,” Beauregard says, “how could I help liking the guy?” Godard quit the publicity job and Beauregard gave him 400,000 old francs ($800) to write a screenplay of Pierre Loti’s Pêcheur d’Islande. Godard went off to the country and came back a few weeks later with a scenario that was really horrible, Beauregard says.

“I’ll bring you a film one day,” Godard promised. Sometime later he showed up with five or six ideas on paper. One was a fifteen-page treatment, written by François Truffaut, about a petty semi-gangster who had lived and died in the St.-Germain-des-Près area. Truffaut’s film The 400 Blows was doing well. Claude Chabrol, who had a couple of solid film credits, said he would come along with the package as technical consultant.

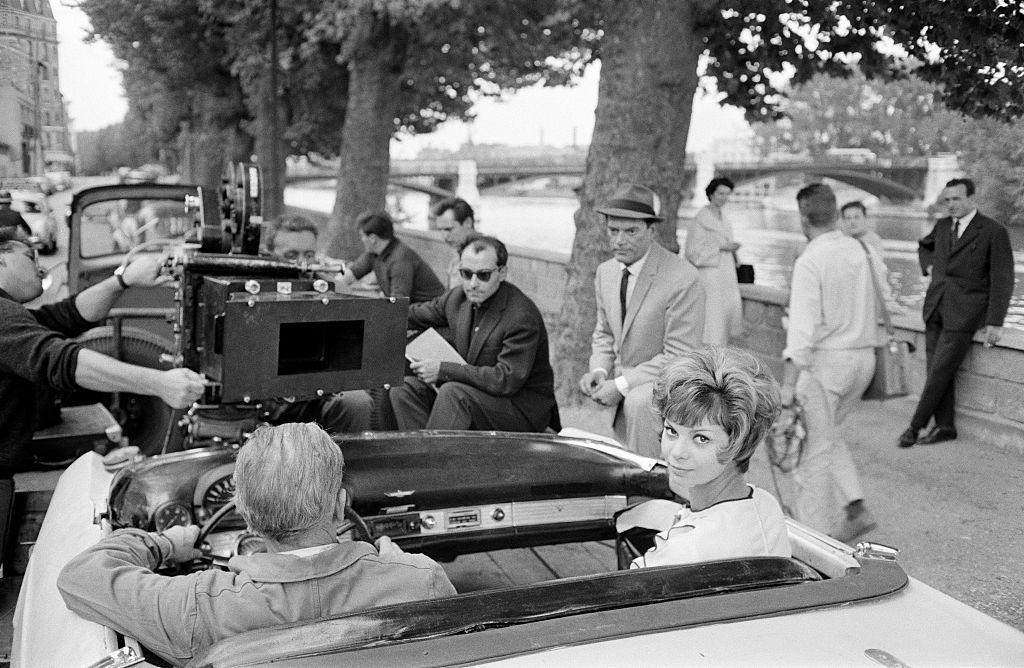

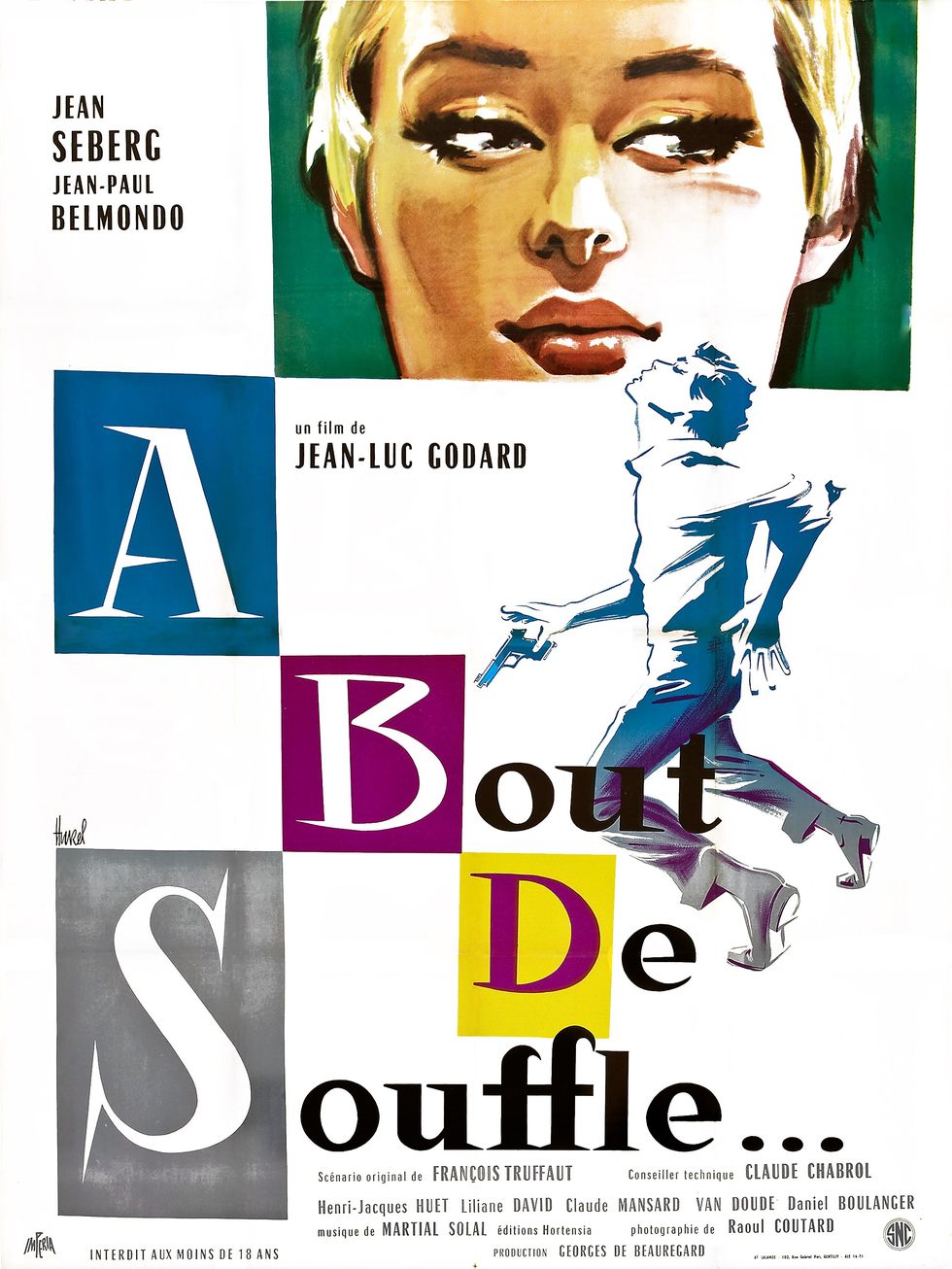

Beauregard says, “With Truffaut and Chabrol in the production, I could take a chance on Godard.” The female lead was played by Jean Seberg, an American girl who had flopped in her first picture (St. Joan, Preminger). The male was a young actor who’d already made a not-yet-released film for Chabrol. His name was Belmondo and he cost $3000. “Today he costs $400,000,” Beauregard said, sighing.

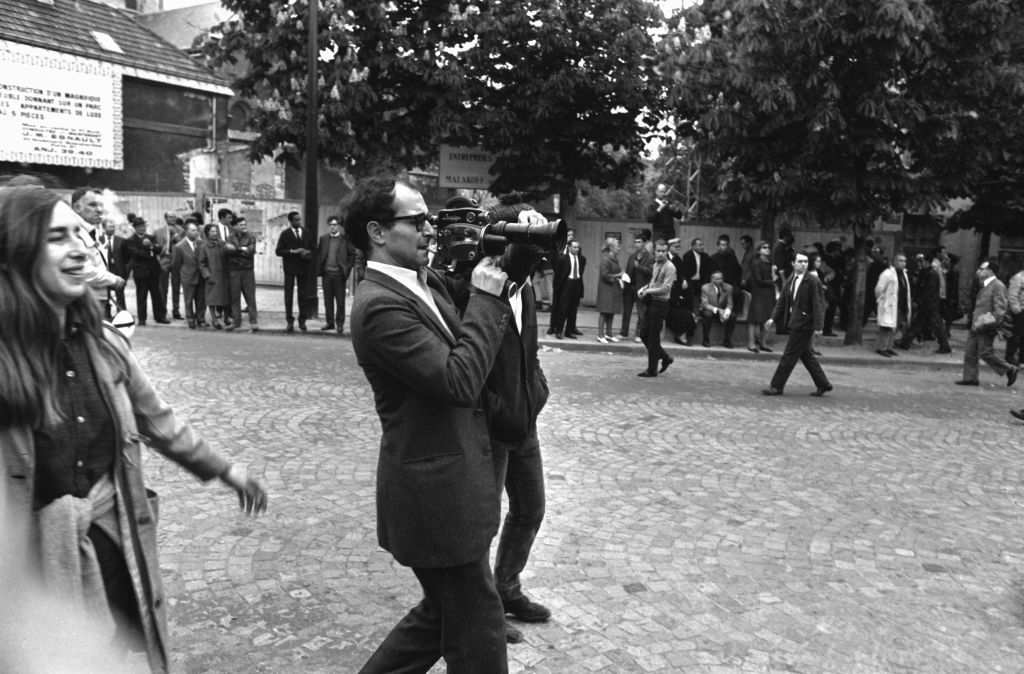

The film was shot in four weeks, in 1959, on locations, without sound. (It was dubbed later, a practice Godard has abandoned.) Godard and his cameraman Raoul Coutard dug up a high-speed film—Ilford HPS—made only for still cameras, usable in available light. It wasn’t made in movie reels; they had to piece it together. The camera was rarely on a tripod, but held in the hand, or rolled on a cart or baby carriage. The purpose was to move fast. Godard had but $70,000 in his budget.

Breathless was released in 1959 and it was a smash. The jump cuts, the dialogue overlapping scenes (“I cut the dialogue when it got boring”), the home-movie quality of the photography made it a watershed for other film makers. It earned around $500,000. Godard got $6000 for the script and the direction. (He now says it was a Hollywood movie.)

“Most directors lose four hours with a plan that requires five minutes of shooting; me, I prefer five minutes of work for the group—and three hours for me to think.

“But it’s tiring to improvise. I always tell myself it’s the last time. It’s not possible anymore. It’s too fatiguing to go to sleep at night asking what are we going to do tomorrow? It’s like an article you write at twenty to twelve which must be delivered to the newspaper at noon. It’s curious that one always manages to write, but to work like that for months at a time is killing.

“For Breathless I wrote each afternoon after shooting; The Little Soldier in the mornings; A Woman Is A Woman I wrote in the studio while the actors were putting on their makeup.

“For me it’s a method imposed by my small budgets. I ask the producer for five weeks, knowing that I’ll have fifteen days of effective shooting. Sometimes you have to wait a whole day to know what you can do. But I ask everyone not to leave. Naturally, they suffer. That’s why I always insist on paying them very well. The actors suffer from another point of view, an actor likes to have the impression that he dominates his character, but with me they rarely have that impression.”

“It looks so easy,” Agnès Guillemot said. “On Pierrot le Fou he would show up with nothing maybe but some newspaper headlines. From that, he would make a scene. Other directors have tried to do it and they fall on their face. It’s like a painter trying to work like Picasso. Godard’s not so intellectual as some others, but he’s got genius, you’d have to call it that.”

“He can’t work unless his wife’s in the film,” someone said. His present wife is Anne Wiazemsky, twenty-one, granddaughter of François Mauriac, the Gaullist philosopher. And when his wife’s not in the film, he makes the lead imitate her. Bardot had to change her walk and her delivery to be more like Anna Karina (his first wife) in Le Mépris.

His favorite painter is Paul Klee, another Swiss. Talks a lot about Brecht, but hasn’t read much of him. Not important, he senses the Brechtian breakdown of the fourth wall—in La Chinoise suddenly he photographs Raoul Coutard, the cameraman, behind his camera. In Weekend, action is interrupted for a posed group photograph of all the actors, looking like the graduating class at some lycée.

The key words are intuition and instinct. Sensibility, too. A man with no skin, no protection, only raw flesh and nerve endings. To Godard everything is a shock, underwear ads, subways, pinball parlors, the Champs Elysées, empty apartments, war, Mao, Hitchcock, Lenin, Fritz Lang, traffic jams, newspapers, revolvers, Anna Karina. There’s only one way to keep it from lacerating him: work. All the time, day and night. Three or four films a year these days. In 1967 he made at least four features, which for most directors is four years’ work. (Bergman does maybe two features a year, Fellini hasn’t done one for four or five years.) Last year Godard made two simultaneously, Made In USA and Two Or Three Things I Know About Her. He worked on one in the mornings, the other after lunch. “I get the sense he’s only alive when he’s working,” says David McMullin, of Leacock-Pennebaker films in New York, U. S. distributors of La Chinoise. “He acts like he hasn’t got much time to waste.”

His defenses are to hide behind those green glasses which are self-prescribed; or to run away, to break appointments, with audiences, journalists, friends. Interviews are old-fashioned, not his style. His publicity is the publicity of confrontation.

“I call him and say, ‘Are you there?’ and he may answer, ‘No.’ Meaning he doesn't want to see anyone,” said Agnès Guillemot.

Reporter: Where do you read?

Godard : At red lights.

He is certainly the only man in history to have written the scenario for a revolution and filmed it a year before it happened. La Chinoise. Then he photographed the real events of May–June, 1968, for French television. Then they wouldn’t show his film. “Ten percent of television is honest. We have to work in that ten percent,” he said.

He sees meaning in the milieu that no one else sees; the message may be several years ahead of the event.

“Even six months is a long lead time on history these days,” said Beauregard.

Godard: “I start more with the documentary and give it the truth of fiction. That’s why I’ve always worked with professional actors.”

Q: How do you usually go about acquainting your actors with their roles?

A: No. No, because I don’t know what the roles are, exactly. It’s building up every day or changing. The more I discover it, I’m telling the actors, of course, but very often I don’t know much about it. To me the best picture is just a close-up of somebody. If he’s saying something, all right, or if he’s saying nothing, all right too. If it’s not always interesting there is at least two or three seconds in an hour that are interesting and that’s already something. That’s why I like Andy Warhol.

Q: Your films abound in montages with words. What do you feel about seeing the word on the screen?

A: Well, they are shots like others. I mean, I think if Hollywood is offering me an adaptation of a novel, I will just shoot on the novel.

Q: Page by page. . . .

A: Why not?

Q: You called La Chinoise a film of montage. Could you say something about the way in which you ordered the structure?

A: Well, it took me three months to edit it after one month of shooting. It would now take three months to tell it. Maybe I can tell you about one thing. For example, I chose on purpose because they were young people, when I put images of Mao Tse-tung or Lenin, I try to show Mao and Lenin always when they were younger. I try to find a picture of Karl Marx when he was young, but I find it only after the editing. And he was very beautiful young—he was just like Warren Beatty when he was young. Every time you saw a picture about Marx, you saw with a big beard. And he was like James Dean when he was twenty years old. And I remember—I only try to work on a logical point of view, going from one shot to another. For example, I don’t know if you remember the shot with the young fellow with the yellow pullover; he spoke lines that were taken from Nikolai Bukharin’s trial. Well, after that shot, who was judging, who was the general attorney at Nikolai Bukharin’s trial? It was Stalin. So after the shot of the young man, I put a shot of Stalin, young. And after that, but who was really Stalin against? He was against Lenin. And who was the first who was angry from that? It was Lenin’s young wife. So I jumped from one shot to another, but from a logical point of view.

Godard is making documentaries of the future in the present. —Pauline Kael

Kirilov, the painter who committed suicide in La Chinoise, was named after the character in Dostoevski’s The Possessed.

“I wanted the audience to be reminded of the first young nihilist students or people in Russia in the nineteenth century. And I wanted the audience to make a link, you say a link?, between the first young nihilist people in Russia and the young Parisian today.”

Q: Does it follow from that that as the nihilists in Russia were a failure, so . . . ?

A: No, no, nothing more. Just to remind of the nihilist and not to say that my characters were nihilists or . . . just to think of it.

Q: Is it your intention in the film to show how young people can become effective activists?

A: Well, my intention, I think I had no intention when I do a movie. Especially this one. Let’s say, there are five characters. There is a sixth character, really; one we never see. And the one who is not being seen is me. But I’m just the elder brother, I mean of the whole family. And so I have no intention of doing something special. I mean they are searching . . . they are searching certain truths which they don’t. . . and I’m searching, too, from the moviemaking point of view.

Q: Can film making be revolutionary?

A: Well, as in anything else, yes. I mean to . . . to me doing this picture. I was beginning again, beginning again, into the pictures. Just as the characters were beginning again into a new cultural life.

Q: Can it be violence to the state? Can it be a terrorist act?

A: Well, from a cultural point of view, I mean, yes. Words can be . . . of course, it helps to kill. It’s not killing directly, but it may help to kill.

Q: The scene in the train with Jeanson. . . .

A: That was all shot in about two hours. Runs twelve minutes.

Q: Was the dialogue written?

A: No. She had a hearing aid in the ear and I told her questions to ask to make it even. Jeanson is a professional revolutionary, a teacher of philosophy, and she is only a student. He said what he wished.

Q: It seemed to me that he was more effective, that he won the argument.

A: I don’t think so.

I MAKE A FILM LIKE A PIECE OF MUSIC. THE CUTS ARE TIMED TO GIVE THE EFFECT. A FEW SECONDS, A FEW MINUTES. SOMETIMES I SHOOT FOR A CERTAIN TIME, OTHER TIMES I CUT. IT DEPENDS ON THE AMOUNT OF TIME WE HAVE TO WORK.

“He loves music,” Agnès Guillemot said. “But he has no ear. He cannot carry a tune. He tried to whistle or hum a musical theme for the sound engineer and the man said, ‘You’re out of tune.’

“‘In comparison with whom?’ Godard asked.”

You can see the music theme in Weekend, starting with the early legato of hostility on the balcony counterpointed by guerrilla warfare between motorists down below. Then the long statement of theme—a tracking shot of 300 meters without interruption—slowly following Jean Yanne and Mireille Dare in their sports car as they squeeze and honk and edge past fifty or sixty cars, trucks, trailers, etc. stopped on the narrow road by the motorcycle cop directing traffic past the racked-up car (a Renault, I think) and the bodies covered with gore. When Godard has color, he loves to show you blood. Once past, they gun the car and Godard builds through andante, vivace, the driving wilder, the accidents huger and more grotesque, the behavior of victims more brutal. There’s a diminuendo, pianissimo of a pianist (Gégaud, scriptwriter in real life) playing Mozart in a farmyard, counterpoint to what’s gone before and what comes later.

“He was planning Weekend for another actor,” Mme. Guillemot said, “but he got Yanne instead. Yanne is a television comedian and has no respect for his profession. He thinks acting isn’t very manly. So Godard changed the character to be more like Yanne, contemptuous.

“I’ve worked with many directors,” she continued, “Truffaut and other good ones. Godard never has any doubts. You ask him something, he tells you, that’s it. No ifs, no uncertainty. He only shoots about three for one, where everybody else shoots about six or seven for one.” (One of every three feet of film Godard shoots is used in the movie; other directors use about one in seven.)

Q: Was that a real Alfa Romeo he burned in Weekend?

A: Yes, it was his own car.

Q: So now he drives a rented car.

A: I guess so. One thing he doesn’t care about is money, or possessions, although he bought Karina a very beautiful apartment. He gives money away, buys things for other people.

Godard advertised for an actress for his second film, The Little Soldier, and a Danish fashion model showed up at Beauregard’s office. Her name was Anna Karina. She appeared in that (in 1960) and a number of others and married Godard at a Protestant church in Paris, in 1961. She wore a white dress and a veil; he wore a dinner jacket. The Little Soldier, which was about the Algerian war, was held up by the French censor for two years.

“He’s been in love ever since I’ve known him,” Truffaut said. “He would meet a girl, and the next day he would be at her door with a bunch of flowers and a marriage proposal. It was always too serious and too absolute. He proposed forty times. I think he sees himself more and more as a second Sacha Guitry.”

Jacques Rivette said, “He and Karina achieved perfect harmony—in destroying each other. Have you ever noticed that he never uses women over twenty-five? Godard was asked to direct Eva(before Joseph Losey), but he refused because of Jeanne Moreau. An adult woman frightens him.”

Cinema is death in action —Cocteau

An obsessive presence of pistols. —Jean Clay, in Réalitiés

Everybody you film is in the process of dying, of getting older. Painting is immobile; cinema is interesting because it comprehends both life and mortality. —Godard

Violence is a constant motif. —Raymond A. Sokolov in Newsweek

When a girl friend refused his attentions, he came after her with a sword. Gégauff tried to stop him, and got stabbed in the thigh. When Karina told him she was going to divorce him, he stormed through their apartment, the one he’d bought and furnished, and cut everything to shreds, furniture, rugs, draperies. When a producer owed him money, Godard went to his apartment and started cutting things up. Before he could do much damage the man wrote a check.

“If there’s one thing he doesn’t care about, it’s money,” Beauregard said. “He gives it away when he has it, buys friends cars, etc. He’s done pretty well, too, got about forty or fifty thousand dollars for Le Mépris.”

He put up $15,000 so Karina could act in a play based on a work by Diderot. When he was making a feature film, based on a play by Jean Giraudoux, it began to rain just as they were ready to shoot. He waited around for a while. He asked Raoul Coutard, the cameraman: ‘How much would it cost to pay off the crew? I don’t feel like making this picture.’ It cost him $6000, which he got by selling the rights to his preceding film, Vivre Sa Vie (U.S. title: My Life To Live), to a producer. The rights were worth at least $20,000. Then Godard went to Madrid where Karina was working in a film.

A conversation with Godard is a series of contradictions, ellipses, dogmatisms. Like his films, like his criticism, a chain of uncompromising statements that advance nothing but his own sensibilities. He makes no effort to rationalize, but presents the raw material in the same unbridged style of his films. The technique is not one of orderly development to climax and resolution, but of shock, juxtaposition, putting it all down, saying it all, letting you take your choice. (“I’ve often thought of showing the audience the rushes and letting them do their own editing.”) He makes sure that nobody, but nobody, will like it all. Truffaut says that everyone objected to a line in The Little Soldier, but it was always a different line. Agnès Guillemot says that the bloody sequence in Weekend, in which two men axe a huge pig on camera, then cut its throat on camera, followed by the sounds of dying and a close-up of pulsing blood, disgusted almost everybody, including the distributor. He asked Godard to cut the scene. “Sure,” said Godard, “if you’ll sign a pledge never to eat pork for the rest of your life.”

THE IMPORTANT THING IS TO KNOW HOW TO DISTINGUISH WHO MIGHT HAVE GENIUS AND WHO HASN’T GOT IT, TO TRY, IF ONE CAN, TO DEFINE GENIUS OR TO EXPLAIN IT. THERE AREN’T MANY WHO TRY.

Leacock-Pennebaker, themselves pioneers in cinéma vérité (See Esquire (May, 1962) La Nouvelle Vague de New York.) and U. S. Distributors of La Chinoise, set up a lecture tour at American universities for Godard, about eighteen in all, at more than $1000 per lecture, to help him raise some cash and help them promote the film. After showing up on time in the right places at N.Y.U., U.S.C. and four others, Godard said he wanted to run over to France to see his wife. He did—and canceled the rest of the tour.

“Talking is not my métier,” he told David McMullin of L-P; “making movies is.” Godard can express himself in English, but not as well as in French. “I’ll make you a movie,” he said.

“The picture I’m going to make for them [it has since been shot] will be called One American Movie. I’m a foreigner, so I can’t make a typical American movie, which would be a Hollywood movie. I’m going to get five or six people, Eldridge Cleaver or some Black-Power person, a New-Left white, a white woman executive, a hippie, a yippy, a black girl. Each one will talk for maybe ten minutes. I’ll ask them questions if they want. Or they can talk. Or say nothing, if they want. Then I’ll get two actors to act out what those people have said. I’d like to get John Cassavetes, who is of two worlds, Hollywood and underground cinema, and Mia Farrow, if she’s available. They’re both white, because there are no black actors.”

Q: What about James Earl Jones?

A : That’s only one. Hollywood has no black actors.

Q: Sidney Poitier? Ruby Dee, Diahann Carroll? And so on?

A : Okay, so maybe there are a hundred or a thousand, but actors are still white. There is no black theatre. My pictures will show that actors are people, and that art can say some things better than real life, and vice versa. They’re both part of the same thing, you can’t separate them.

(In La Chinoise the character Guillaume, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, says he’s an actor and will give you an idea of what the theatre is. Some young Chinese students demonstrated in front of Lenin’s tomb in Moscow, he says, and were pushed around by the Russian police. They retreated to the Chinese Embassy and later called a press conference. A young Chinese with his head entirely bandaged slowly unwound the bandages with the Lifeand Paris Match photographers shooting, and when all the bandages came off they saw, instead of the bloody face they expected, an unmarked visage. And they began asking, what’s it all about, are these Chinese comedians?)

They hadn’t understood that it was theatre . . . real theatre . . . a commentary on reality. Something out of Brecht . . . or Shakespeare. —La Chinoise 136-141, reel 1A

“We’ve made art into a box,” says Godard. “This is art, that’s not. Our museums are full of old Egyptian art. Tombs of art. We should throw it all out, maybe save one example. If Malraux were a real Minister of Culture, that’s what he’d do. He wouldn’t have La Joconde in a room, but on the Champs-Elysées, now you have to go to see it, you can’t talk, you can’t smoke. What right have we got to tell the people what is art?

“Should we go into a factory and bring Shakespeare to the workers? Better they should close the factory for a day and let the workers go see what they want.

“What I’m trying to do is not bring art to the people, but come from the people. It is very hard.”

“He doesn’t start with a script, but with notes, maybe three pages, maybe twenty,” said Susan Shiffman, script girl on most of his films. “He says he can’t write a script. But when he wanted to do Le Mépris with Bardot, they [Carlo Ponti, Joe Levine, Beauregard] asked him for a script. He wrote a one-hundred-page treatment to show why he couldn’t write the script. They insisted on a script or they wouldn’t give the money. So he wrote a one-hundred-page script.”

“If he uses no script, why does he have a script girl?”

“Because he’s lonely,” she said.

I’M NOT GOING TO MAKE ANY HOLLYWOOD MOVIES.

(A “Hollywood movie” is not necessarily made in Hollywood. But it is a film with the following ingredients: The Mitchell camera. Twenty technicians and assistants. Big budget. Script. Theatre distribution. Promotion.)

Jean-Luc Godard, German student-activist Daniel Cohn-Bendit, and rebel producer Gianni Barcelloni have picked up financing from capitalist tycoon Angelo Rizzoli’s Cineriz Distribution Associates for an anti-establishment western calledWind From the East, which Godard will film entirely in Italy. . . . [Cast includes] actor-revolutionist Gian Maria Volonte, Anne Wiazemsky, anarchist director-actor Marco Ferreri, and possibly street orator . . . Vanessa Redgrave. . . . Cohn-Bendit, a Godard aide-de-camp . . . will develop the four-page treatment. . . . [Carlo] Ponti . . . backed away, stating, “In five previous films with Godard I lost two million dollars and ten years of health.” Godard has his heart set on bringing in a big commercial click and using the profits to help finance the international student movement. —Variety, March 26, 1969

“Working as he does,” Beauregard says, “some days he just doesn’t feel like shooting, but some days he wants to shoot for twelve hours. With a big payroll eating up the budget, he’s got no choice. His ideal setup would be to work entirely alone, with maybe a couple of assistants, a hand-held camera and a synchronized tape recorder. He likes everything very neat. He’s Swiss, you know. He likes to organize it all himself. Now he’s got his own producing organization.”

“Why should we be tyrannized by 35mm?” asks Godard. “Who needs the Mitchell camera? All those people? I would rather make a hundred films with one person than one film with a hundred people. I’m working in 16mm, now. They can show that in schools and colleges, union halls, churches. And some theatres have 16mm. You can blow up 16 to 35mm if you want theatre distribution. And I will go to Super 8. You know it’s so simple that a professional cameraman doesn’t know how to operate one? All you do is point it and press the button. And there’s videotape, amateur models now made by Sony and some others. Not yet in color. So we can make films so cheap we can afford to do one a week. If it’s no good, throw it away and start another.”

Q : Would you evaluate La Chinoise as philosophy by means of cinema?

A: No, the contrary.

Q: Do you personally advocate violence in a revolutionary cause?

A: Yes. Yes, but you have to . . . obviously in France you don’t need to . . . kill people or throw bombs. Maybe if you throw a bomb, you have to try not to kill, not to kill too many people. But in another country, I wouldn’t say.

Q: Que pensez-vous de l’avenir immédiat, et moins immédiat, du cinéma français? Etes-vous optimiste, pessimiste, ou attentiste?

A: J’attends la fin du cinéma avec optimisme.

Fifty years after the October revolution, the American cinema reigns over world cinema. There isn’t much to add to that fact. Except in our modest sphere, where we are trying to create two or three Vietnams in the bosom of the immense Hollywood-Cinecittá-Mosfilms-Pinewood empire. Not so much economically as aesthetically, that is to say fighting on two fronts, to create national cinemas—free, brothers, comrades and friends. —From Press Book, La Chinoise

We arrived at Le Bourget about one-thirty. Godard turned the car over to Avis. (“I always use Avis, I like their slogan: ‘We’re only number two so we try twice as hard.’”)

“What time’s your flight?”

“Two-thirty.”

“Then we have time for lunch.”

“No lunch, just a coffee.”

So we sat at a round table in the bar and the waiter came over.

“A sandwich and a beer,” Godard said.

“What kind? Ham? Cheese?”

“Ham.”

Godard bought some newspapers and left to board the B.E.A. plane for London. He was carrying no valise, no briefcase, no envelope, nothing except the newspapers.