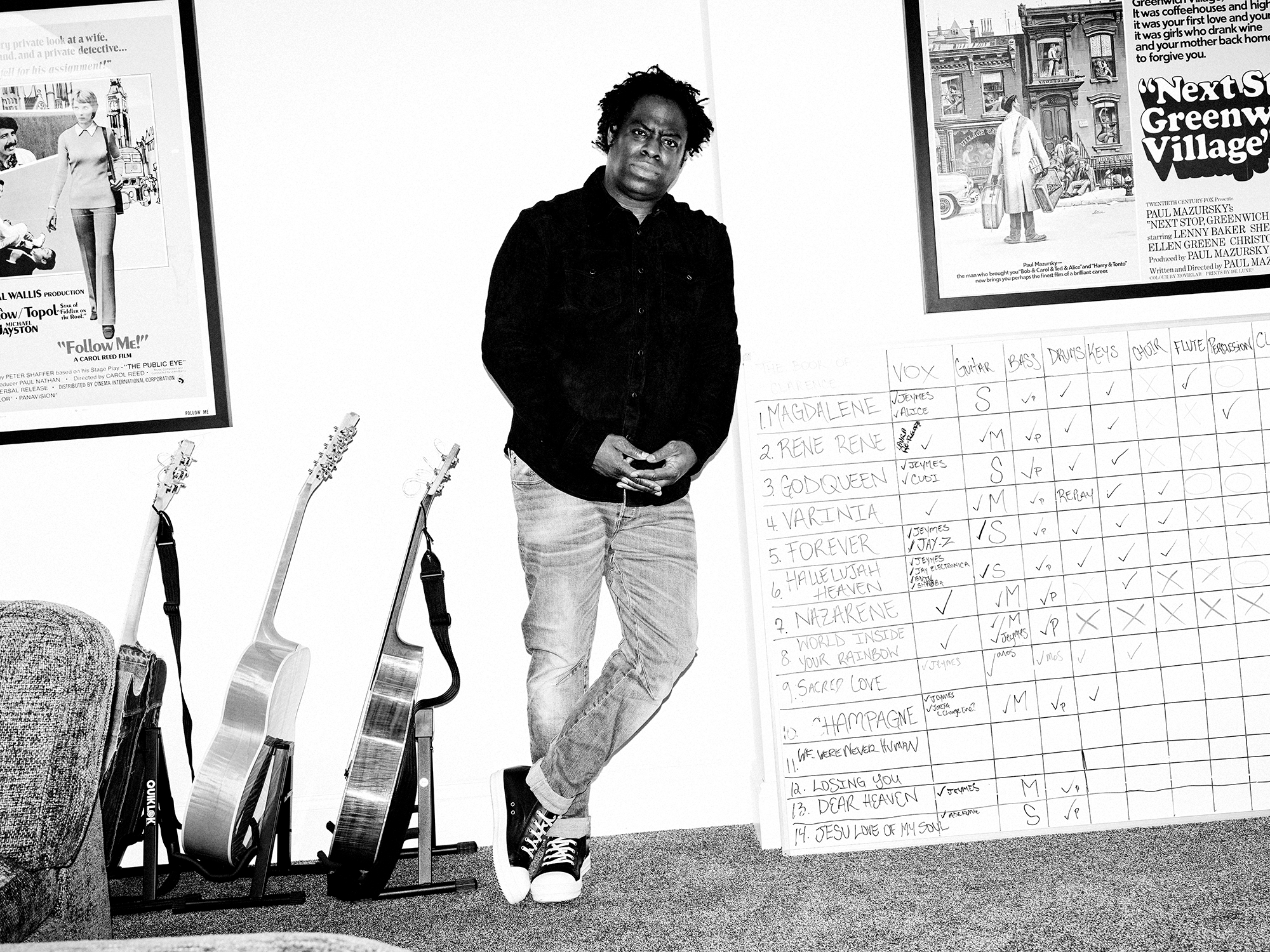

When, this past June, I turn up to interview Jeymes Samuel, the 44-year-old British writer and director of 2021’s outrageously stylish, genre-busting Western, The Harder They Fall, he is — unlike Ernst Stavro Blofeld with 007, and to use the kind of pop-cultural reference with which Samuel’s speech is peppered — not expecting me. As instructed, I have come to the converted church in north London that is home to Air Studios, the recording-studio complex founded by Beatles producer Sir George Martin, where Samuel is overseeing the soundtrack for his new film, The Book of Clarence; I have very little information about the movie at this point, other than that it is set in Biblical times, and stars the American actor LaKeith Stanfield. In fact, it is still some months from being completed, and the PR machine by which interviews are often arranged has yet to grind into gear; but, I had been told — by a nice woman in America, whose email I was eventually given by a series of other nice women in America — it would be fine to stop by for a chat.

At reception, however, the man at the desk has no record of my name and — like a surprising number of people, given he’s one of the most charismatic and successful British directors working right now — doesn’t seem entirely sure who Jeymes Samuel is. Still, he puts in a call to the studio that has been booked out for the film, to see what he should do with me. In usual circumstances, a mishap like this would mean I’d be sent packing; perhaps told later, by a less-nice woman in America, that something had “come up”, and that the interview would need to be rescheduled for 3.15am, on a Saturday night, on Zoom. But no! For that is not how Jeymes Samuel rolls. The man at reception puts down the phone and shrugs. “Apparently you can go straight in.”

And there he is, inside the dark-walled recording suite, sitting on a fancy swivel chair in a T-shirt, bright-blue Issey Miyake trousers and Nike high-tops, his face beaming. Flanking him on either side of a ginormous mixing desk are various music-boffin types, pressing buttons and muttering into microphones; on the other side of the studio’s internal window a full orchestra sits, bows raised, awaiting further instruction. “I forgot you were coming!” Samuel announces, cheerfully — no! Joyfully! — before introducing all the music boffins, explaining what kind of button-pressing they are doing, and then proclaiming to the room, as though my arrival is not something that risks derailing their already-tight schedule but should, in fact, thrill them: “This is Miranda from Esquire!”

It’s hard fully to convey what meeting Jeymes Samuel is like, so here’s how some others describe it.

“I met him in a music space,” says the polymathic musician Jay-Z on a video call. Under his given name, Shawn Carter, Jay-Z produced both The Harder They Fall and The Book of Clarence. Before Samuel had success as a director, he was known mostly as a composer, producer and recording artist, for which he mostly went by the name The Bullitts; a decade or so ago, he was working with the artist Jay Electronica, who is signed to Jay-Z’s record label, Roc Nation. “Jay Electronica was trying to squeeze a little more budget out of me,” Jay-Z recalls, “so he was weaponising Jeymes, he was using him as a tool — that’s how talented Jeymes is. He had this whole string section set up to play for me, like, ‘Yo, listen to these strings!’ It was Jeymes on the phone. I don’t think I extended the budget, but I definitely said, ‘I’ll meet this guy.’”

Later, Jay-Z invited Samuel to work with him on the soundtrack for the 2013 film adaptation of The Great Gatsby, and arranged an introduction with the film’s director, Baz Luhrmann. “I could be mythologising this,” Luhrmann tells me in another video call, of his own first encounter with Samuel, which sounds not unlike Harry Potter’s first meeting with Hagrid, “but at the time I had this townhouse in MacDougal Street in New York. My kids were there and it was dinner time. I think it was winter, and the doors opened, and the snow, or the cold, swept in, and then this person comes in and drops his coat. And just his sheer energy, uplift, passion… When he left, even my children were like, ‘Dad, who was that?’ And that’s the impression you get when you meet him; you go, ‘Who is that?’”

OK, that’s how they describe it, and now I’ll have go. You don’t so much meet Jeymes Samuel as get pulled into his orbit, swept along in his tidal wave, embraced by his aura and — fuck it — warmed by his light. Or, as one of the production-company interns for The Book of Clarence tells me fondly, when, several hours after I had expected to have been booted out, I find myself still sitting in Air Studios and wondering who’s going to pick up my kids from school: “Aw, has Jeymes kidnapped you? Yeah, he does that.”

It’s not surprising that his feature films — or really just “film”, given that at the time I meet him there has been only one — display something of their progenitor’s confidence and charm. The Harder They Fall, which was made by Netflix and cost it $90m, debuted in November 2021. It starred an all-Black lead cast including Idris Elba, Jonathan Majors, Regina King and Stanfield again, as sassy, souped-up versions of real-life Black and mixed-heritage figures from the American West, with the kinds of names you’d want such people to have: Nat Love, Rufus Buck, Stagecoach Mary, Cherokee Bill. Divided into two gangs of outlaws, their violent — and, in the case of goodie Nat Love (Majors) and baddie Rufus Buck (Elba), very personal — rivalry is followed through to its not-entirely-but-largely-deadly conclusion, against an energising soundtrack of reggae, Afrobeat and hip-hop.

Plenty of critics were wowed. The New York Times called it “a high-style pop Western, with geysers of blood, winks of nasty, knowing humour and an eclectic, joyfully anachronistic soundtrack”; for Rolling Stone it “revels in the freedoms of pastiche, reckless violence, and glossy, staccato style”. Even the outlets that didn’t like it so much couldn’t help but be a little bit seduced: “The Harder They Fall is a mess,” wrote New York magazine, “but it’s a fun mess.”

Perhaps more importantly, though, it got watched. By the decidedly unsexy metrics with which success is gauged these days, in the first five days after its release The Harder They Fall had, according to market measurement firm Nielsen, received close to 1.2bn minutes of streaming views, making it by far the most popular film of that period and a bona fide hit.

The most astonishing thing of all though — mind-blowing, really, and not just for the assuredness of its direction, the starriness of its cast, but also for how much money the whole thing cost — is that The Harder They Fall was Samuel’s debut. How does a seemingly untested director appear on the scene so fully formed, so fully backed, so fully trusted, and then — sure enough — comprehensively deliver? When, after The Harder They Fall’s punchy, funny, ultra-violent, eight-minute opening sequence, you see his name flash up for the first time, red lettering on black, “A Jeymes Samuel Film”, you can’t help but echo the junior Luhrmanns in asking: who is that?

Which is what I spend my time at Air Studios, and a second meeting at a post-production house in Soho a few weeks later, trying to work out. At least I thought that’s what I was doing, but transcribing it later, I discover that quite a large amount of our time together has been spent watching clips of Samuel’s delightfully insane lockdown project, The Palindrome — a feature-length whodunnit he orchestrated on Instagram Live, centring on Samuel’s alleged theft of some aloe-vera toilet paper from Jay-Z’s after-Oscars “gold party”, and featuring cameos from stars including Adrien Brody and Morgan Freeman. “Sometimes I honestly think I’m the best storyteller in the world,” he tells me, wide-eyed, while I’m trying desperately to work out what’s going on. “While everyone’s using Instagram to show their fingernails, and show what they’ve eaten, I’m like: the smartphone is the biggest story-telling device since the invention of the book!”

We do at least start off by talking about The Book of Clarence, short clips of which are playing on repeat on the monitors high up on the walls, as the orchestra fine-tunes the cues. Once again, the film mainly stars acclaimed Black actors, including Omar Sy, Teyana Taylor and David Oyelowo, and a couple of pretty decent white ones, including James McAvoy and Benedict Cumberbatch. Like The Harder They Fall, it presents an alternate history to the one that Hollywood’s classic genre movies — in this case the mid-century Biblical epics like William Wyler’s Ben-Hur or Cecil B DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, which Samuel says he loves — have traditionally proposed.

“It isn’t about the Bible, but it takes place in the last days of the Christ,” Samuel says of his film. “If they tell you a Bible story, you wouldn’t get the story of the guy around the corner. Or the person who sold Jesus his sandals. Where did Jesus get his sandals from? I want to know! Who was that guy? What club did they go to? You telling me they didn’t have nightlife in the Bible days? Who was the village swindler? Are you telling me no one ever rode those chariots illegally on the street? I want to see that movie!”

As becomes apparent later, when a trailer is released, The Book of Clarence does contain, thankfully, at least one illegal chariot race. It is set in Jerusalem in 33AD and follows a young man, played by Stanfield, who sees the growing adulation surrounding Jesus Christ — whom we first see, silhouetted in a golden light, accompanied by a bombastic take on Prince’s “I Would Die 4 U” (nice!) — and fancies himself a bit of the Messiah action. Naturally, as we learn via some repartee with Clarence’s buddy Elijah, played by another The Harder They Fall alumnus, RJ Cyler, Clarence’s hustle works a little too well.

“Clarence is your everyman,” Samuel explains. “Clarence is literally just a dude in the hood, through the eyes of which we look at that era and learn stories. Everyone either is a Clarence or knows a Clarence, right? He wants better for his mother. He wants better for himself. He wants to be someone. And he does whatever he can to just get by. It’s just who Clarence is. He’s a lovely guy! Like, Clarence is me, in the hood. He’s all the people that I knew and grew up with in Mozart Estate. We were all just Clarences.”

The Mozart Estate is the housing estate in west London on which Samuel was raised and which he refers to often (childhood settings are always formative, but probably more so when dealers are selling crack in the stairwells). By the 1980s, when he, his four siblings and their mother lived there — his father, he says, not seeming to want to expand, died when he was “very young” — the Mozart Estate was in a spiral of poor-quality housing, managerial neglect, vandalism and increasingly serious crime, leading to notorious gang conflicts in the 1990s.

Nevertheless, in the Samuel household it was a different story: he describes his mother, a hospital sister, as a film addict, who instilled in him a love of cinema and with whom he would debate over the dinner table, say, the relative acting merits of Laurence Olivier (“I love him, but don’t think he made a seamless transition from theatre to film”). He credits his “wildly energetic and creative” siblings with exposing him to music (his older brother, a fact that probably shouldn’t be in parentheses, is the musician, Seal).

For Samuel, the if-you-can’t-beat-’em-join-’em rationale towards his surroundings was never going to apply. “I would get all the drug dealers round to my mum’s house on Sundays,” he says, “and I’d be doing Film Noir Sundays with my projector, showing them Double Indemnity. I just kind of ‘terraformed’ the area — if you watch War of the Worlds, Tom Cruise walks out of the house and it’s all red: the aliens have ‘terraformed’ the environment to be able to inhabit it — meaning just making everyone like myself, in order for me to survive creatively. I’ll be giving these lectures on Jack Hawkins, Alastair Sim, John Mills, John Gielgud, Claude Rains, while I’m listening to Wu-Tang Clan, Mobb Deep, Jay-Z… I’m an amalgamation of every single thing that I love, both cinematically and musically.”

Samuel says as a kid he was, “super, super clear in my vision. I think I always did the right things to get there,” though he admits the minor transgression of stealing his first guitar from school, which he taught himself to play. As a teenager he worked at the Post Office and, briefly, a snack stand at Wembley Arena (he says he got fired for eating the popcorn), to be able to buy a computer, sampler and keyboard. From a young age he was making music and shooting film, and sees the two as almost indistinguishable; “I see music and I hear film,” is a phrase he likes.

“I think we connected because we’re both from tough neighbourhoods,” says Jay-Z. “He is from the hood in London, I’m from the hood in Brooklyn, and we were both in these environments, walking around, big dreamers. And maybe kind of weird to others, early on. I was walking around with a notebook in my hand — and in those environments kids didn’t walk around with notebooks — and he’s walking around with a guitar and they’re like, ‘What are you doing?’”

At 18, Samuel signed a recording contract, and as well as putting out his own material he began writing for other artists, his first being a song called “Serenade” for the Icelandic singer Emilíana Torrini, for her 2005 album Fisherman’s Woman. He started to produce and write for an eclectic mix of British musicians including Mr Hudson, Estelle and indie band The Feeling, while also making experimental extended videos for his own music — one a film noir shot in Paris, another a reworking of Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou — starring glitzy actors such as Rosario Dawson and Lucy Liu.

When Baz Luhrmann and Jay-Z began talking about a soundtrack for The Great Gatsby that would mix musical genres — to convey the historic thrill of jazz music by infusing it with the contemporary energy of hip-hop — Jay-Z thought immediately of Samuel, and brought him in as executive music consultant. “I was like, ‘I know just the person who speaks both those languages like myself,’” Jay-Z says. “I reached out to Jeymes and we sat down and cooked up these things. Had we had full rein — it was Baz’s movie, not ours — we might have pushed it even further, but it was Baz who allowed us to explore this space we were always talking about: how to fuse music and film in a super-interesting way.”

Luhrmann says he could sense Samuel’s appetite for film-making even then. “A lot of people say, ‘I’m gonna make a movie,’ but they don’t,” the director told me. “The thing with Jeymes is, he talked about the movie he was going to make — in fact, I’m pretty sure he was talking about The Harder They Fall even then — and when he said, ‘I’m gonna make this movie,’ you just knew he would. He had a natural thirst to understand the processes of large-scale film-making.”

Samuel had, smartly, produced a proof-of-concept short in 2013 called They Die By Dawn — a 50-minute film with some of the characters in The Harder They Fall (Nat Love, Stagecoach Mary) played by a different, though equally starry group of actors, including The Wire’s Michael K Williams, Breaking Bad’s Giancarlo Esposito and musician Erykah Badu. And how, I ask, did he get them to agree? Agents? Publicists? “No! I’ll go to their house! Erykah Badu in Brooklyn, Giancarlo Esposito in Upstate New York somewhere… I’d find someone who was their friend and they’d say, ‘I want to come over with my friend Jeymes.’ I had a strong feeling I’m good at getting my ideas across.” (No kidding!)

Really though, the idea for the film stretched back even further, says Samuel. “When you’re in a hood environment, for us the only way out was the pen. And the pen meant two things: the penitentiary, and the pen with ink. That’s why I’ve never suffered writer’s block: there’s no such thing as a blank page to a person from an oppressed environment. You look at a blank page and you just see a plethora of opportunity.”

They Die By Dawn, The Harder They Fall and, now, The Book of Clarence are all films about representation — reminding the industry, and audiences, that there are and were lives beyond the ones those in power have chosen to preserve and portray; but they also just enact representation, in a joyous, unselfconscious way. “I made it because I was starving, I was starved of seeing those people in that kind of environment, seeing people with the background I come from,” Samuel says of The Harder They Fall. “I remember when Hugh Grant and Julia Roberts made Notting Hill, I was like, ‘I don’t know how they special FX-ed out all the Black people! Because the whole thing takes place on Portobello Road!’”

During the process of making the films, he also chooses to disregard some of the accepted industry norms. He says he believes his job as a director is “to make sure everyone has so much fun” and says that on set he’s “the person who messes about most”. He shows me footage from the Italian hilltop town of Matera, which doubled as Jerusalem in The Book of Clarence (as it did before for Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, he informs me), where Samuel would take advantage of any break in proceedings to blare out music from a large portable speaker, and encourage the cast, and eventually, the more reticent local crew, to dance to Burna Boy, or Hall & Oates. “I’m Black! I know what my people like!” he says. “I was playing the Once Upon a Time in America theme, the Italians are crying! You could be Daniel Day-Lewis, or Laurence Olivier or Charles Laughton; if you are in a Jeymes Samuel film, there’ll be music on set. Be as method as you like. My method is music!”

He describes going out of his way to make LaKeith Stanfield laugh after a challenging scene — “I’ll hug him, crack a joke” — and doing the same with Idris Elba when he was “in Rufus Buck mode” on set in New Mexico for The Harder They Fall. According to him, Elba eventually caved, and snapped back to his normal British accent to request Samuel play him Norman Connors’ 1976 R&B classic “You Are My Starship”. (I tried to find out how Elba felt about it, but the ongoing Screen Actors Guild strike prevented him answering the question. His publicist did say, however, “He loves Jeymes.”)

What about moments of tension on set? Surely there must have been a few? “There’s always moments of conflict on set, but not with me,” Samuel says. “I’m from the hood! We know how to do conflict properly! These Hollywood conflicts, and entertainment-industry conflict — it’s not conflict! If you come from the kind of surroundings I come from, the last thing you ever want is conflict. There’s literally no need to ever be angry on a film set. You’re storytelling!”

Eventually, and in the nicest possible way — as Elba knows, and Jay-Z knows, and I, in a small way, discover — Samuel will bend you to his will. As Luhrmann puts it, “Jeymes can make you see it, he can make you believe in it, and then he can make you do it.” Still, I can’t completely get my head around how someone can be so full of beans, so much of the time. (The only time I see even a hint of a shadow pass across his face is when I ask him about his private life, which he says he prefers to keep to himself, though he says he “has a family” and that his eight-year-old son is in The Book of Clarence. Then he calls me a “sausage”.) On this he is, as ever, persuasive.

“I was like Obelix,” he says. “Remember [in the Asterix books], he couldn’t have no magic potion to fight the Romans, because he fell in it when he was a kid? That’s why he’s so big? It’s like I fell into the energy cauldron when I was a kid. I’ve always, always had it. I had excess energy. I grew up where people were doing mad drugs: ‘I’ve got more energy than you guys and you guys are using artificial substances!’ Mine doesn’t turn off, and I don’t get a hangover! I have boundless amounts of energy, which is why I can write, produce, direct, compose and do all the songs on the soundtrack. It never ends. It’s just all fun.”

The Book of Clarence is still upcoming — it’s due for cinematic release in January — and Samuel is already attached to “a couple of TV shows for Netflix”, and an adaptation of two graphic-novel series, Irredeemable and Incorruptible, but he has another project on his mind first. It will be, he says, “a modern-day story. It covers the African continent. And America. And Europe”. He can’t say more than that, though he adds, “I’m always excited by what I make. I think The Harder They Fall’s amazing. I think The Book of Clarence is amazing. So this one… Oh. My. God.”

Does he have the financing? Studio support? “It’s too early,” he says, “but in the words of Frasier Crane, ‘I’m listening.’ I want to start filming next year.”

It’s hard to imagine it will take him long. Jay-Z, certainly, is already onboard (though he’s more tight-lipped on the details; when I ask him if it’s the “whole-of-Africa” project, he sighs affectionately. “The only thing about Jeymes,” he says, “is he can’t hold water”). It is also Jay-Z who sums up the phenomenon of Jeymes Samuel the best. “You never want to lose that child-like wonderment, and Jeymes has that,” he tells me. “The manifestation of his dreams is wild, and the more they happen, the wilder he dreams.” ○

“The Book of Clarence” is out on 12 January

Miranda Collinge is the Deputy Editor of Esquire, overseeing editorial commissioning for the brand. With a background in arts and entertainment journalism, she also writes widely herself, on topics ranging from Instagram fish to psychedelic supper clubs, and has written numerous cover profiles for the magazine including Cillian Murphy, Rami Malek and Tom Hardy.