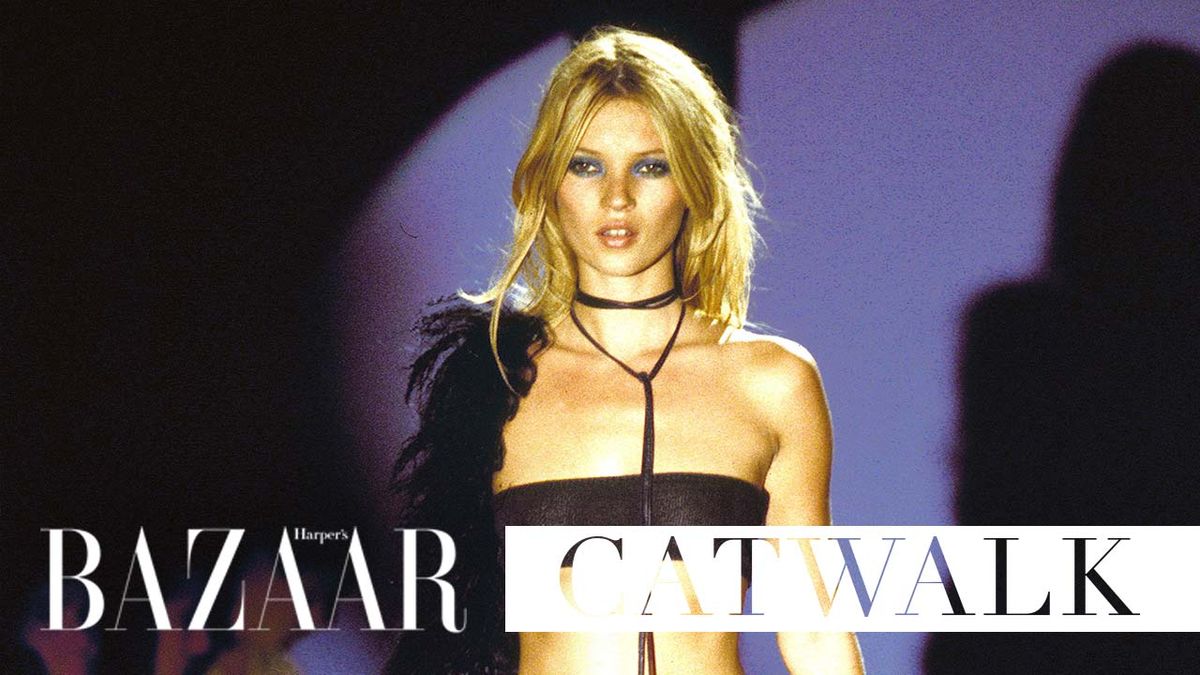

In the summer of 2013, at a photo studio in north London, the photographer Craig McDean, the stylist Katy England and various Esquire rubberneckers, including me, gathered to shoot Kate Moss, the pin-up of her (our, my) generation, for the cover of Esquire. There are many standout moments in the career of a magazine editor — we’re very spoilt — but this, for me, was a highlight. To watch Kate pose for the camera in real life is equivalent to what it must have been like to watch Picasso paint, Maradona dribble, Fonteyn dance. She is the GOAT. To run alongside Craig and Katy’s beautiful photos, I wrote the breathless encomium below. We republish a version of it here as a mark of our undying admiration, on the occasion of her 50th birthday. Happy birthday, Kate.

Her face has changed. It’s more feline, less angelic. The heavy lids are heavier. The eyes have always flashed, now they burn. No longer the waif, today she is curvier, more womanly. Her skin is tawnier, her movements more languorous. Experience has shown innocence the VIP exit. But some things stay the same: the bones still catch the light like no girl’s before or since, slicing it with a nail file, or a Stanley knife; the pout remains as insolent as ever; the nose still wrinkles disarmingly; and the uncorrected teeth, like their owner, are as British as last orders at the bar. Another thing that does not alter: her power to seduce. Those of us who have grown up with her, alongside her – we have not ceased to desire her, and she has never stopped giving us reasons to do so.

Oh, dear. You’re going to have to forgive me. Impossible, I’m finding, to write about Kate Moss – the way she looks, the signals she transmits, the effect she has – without joining both the cultural studies pseuds and the sweaty-palmed sex pests. She is sensational. Coarse and refined at the same time. Soignee one moment, slovenly the next. Rare and exquisite, common as muck. Writing about her in the London Review of Books recently, Kevin Kopelson observed that she is one of only two “celebrities” to embody such contradictions. (The other, according to Kopelson, is the woman who sat for the Mona Lisa.) Famous people are typically renowned for the singularity of their appeal: they are either good or bad, clever or stupid, ugly or beautiful. But Kate is human and divine; powerful and vulnerable; ideal and real; glamorous and earthy; Ophelia and Lady Macbeth. And our feelings for her are contradictory, too. They are blameless: we love her. They are impure: not to put too fine a point on it, but we would like to love her more.

On Kate’s supposed ordinariness, Kopelson quotes Simon Doonan, the creative director of Barneys, in New York: “She’s not a high-born girl. She’s a working class slag from a crap town, just like me!” This statement may well be factually correct, with apologies to Croydon (and Reading, Doonan’s hometown), but it’s also wildly misleading, because it ignores the essential Moss dichotomy: she’s also a multimillionaire supermodel-socialite, mate, and, according to Vanity Fair, “the most beautiful girl in the world.” So not just like you, at all. Much better, on the yin and yang of Kate, is David Bailey: “She’s the kind of girl you wished lived next door, but she’s never going to.”

To complicate matters considerably, what they don’t tell you, the people who know her and work with her – because how could they admit it, after all those effortful, expensive, fitfully brilliant attempts to capture her appeal, to frame her fearful symmetry? – is that no single photograph, or moving image, or painting or sculpture or essay, least of all this one, does her justice. In the flesh, she is even more astonishing, more thrilling, more confounding, than in all the representations of her. I have met her, briefly, on a number of occasions over the years, socially and professionally and each time gone pathetically to pieces in her presence. It is as if, to run with Kopelson’s ball, rather than being diminished in the flesh, Lisa del Giocondo turned out to be even more mesmerising than in da Vinci’s portrait. Who can say it’s not possible?

Of all those many photos and artworks, Kate once said, quoting Jean Cocteau: “The more visible you make me, the less visible I become.” Eventually, she eludes even those with the sharpest eyes and the greatest skill – even Lucian Freud, who painted her, and Marc Quinn, who sculpted her, and Tracey Emin and Chuck Close and Richard Prince and Banksy, who Warholed her, even they can’t catch Kate Moss, only versions of her. Neither can all those fashion photographers who grew up with her, who have returned to her as a subject over and over again, each time coming away with a different Kate: Mario Sorrenti and David Sims and Nick Knight and Glen Luchford and Craig McDean, who photographed her for Esquire, and scores of others, all at the top of their game.

Not even Calvin Klein or Burberry or Versace or Chanel or Topshop or Rimmel or Virgin Mobile, for all the countless millions spent on borrowing her cool, her attitude, her style, can ever possess her: she’s only ever on loan. And anyway, unlike any other fashion model, it’s not so much the clothes she’s paid to wear that girls want to own, it’s the looks she puts together herself and with friends, for parties and shopping trips and festivals, that are most slavishly copied.

Today, Kate’s allure is undimmed. She is more famous, most successful, more popular and sought-after than ever. This much we know. What else do we know? We know the biographical details, the wiki-factoids. Five feet seven inches. Brown hair, hazel eyes. Comes from the rowdy suburbs of south London. Daughter of a travel agent and a barmaid, divorced. Discovered at 14 by Sarah Doukas, of the Storm model agency, while passing through JFK on her way back from a family holiday to the Bahamas. “Great bones,” said Doukas. Went to castings in her school uniform, and at weekends plunged into late Eighties London nightlife, dancing alongside designers, PRs, pop stars, sleeping on the floors of photographers, hairdressers, stylists.

Then, 1990: her second cover of The Face, grinning on a black and white beach, scrunching up her nose for a celebration of acid house’s “3rd Summer of Love”. Those photos were taken by the late Corrine Day, who subsequently made Kate real-world famous, aged 18, with a series of anti-fashion fashion images, one in particular in which our sylph-like subject, her pink singlet and baggy G-string accessorised with a crucifix and an insouciant stare, stood gawkily in front of a white wall decorated with a flaccid string of fairy lights. You can see that photo now at the V&A, where it is part of the permanent collection.

All of a sudden she was an avatar of Nineties grunge, the face and body of Obsession and Opium, as well as of that spurious media confection “heroin chic”, a lighting rod for controversies surrounding the supposed glamorisation of drug use in fashion and pop culture, negative body image in young girls, the promotion of paedophilia and pornography and the failure of England to qualify for 1994 World Cup. (I may have invented one of those). By then she was already plastered on billboards across the world, straddling Marky Mark for Calvin Klein, the first of many lucrative global contracts. In the process, despite being presented as an antidote to the gaudy maximalism of Eighties fashion and the strident, bodacious perfectionism of the supermodels who bestrode the world before her, she had somehow become one of them, perhaps the last of them, photographed by Richard Avedon, Bruce Weber, Peter Lindbergh, Herb Ritts, championed by John Galliano (who called her his “rough diamond”, “the only real muse I’ve ever had”), the late Alexander McQueen, and feted by the magazine editors – fellow Brits all – with the most influence.

And so, in turn, she became a celebrity, just as celebrity culture was simultaneously exploding and tightening its grip, a “style icon”, a pin-up, a brand, her look arguably the most imitated and influential in the world. (She even made Wellington boots trendy; think about that for a moment). She lived for a time in New York with her then boyfriend Johnny Depp – “a fabulous constellation of cheekbones,” someone said at the time – and through him she befriended Keith Richards, Hunter Thompson, Marianne Faithful and other legendary hell-raisers. Tales of her own hedonism began to gain in currency. She returned to London in time to preside over Britpop, the Primrose Hill set, the Met Bar, the Groucho and all the ensuing riotousness and ribaldry of turn of the century London, the coolest girl in the coolest city in the world.

For a time she stepped out with Jefferson Hack, the magazine editor and publisher, and they became parents, in 2002, to Lila Grace. Later she embarked on what appeared to be a tempestuous romance, and a broken engagement, with Pete Doherty, the junkie musician. In 2005 she appeared on her most infamous cover: apparently taking cocaine on the front page of the Daily Mirror, cementing her position as the nation’s caner-in-chief.

For a moment, as her clients distanced themselves and dropped her from campaigns, it seemed she was teetering, and might even fall. But she did the requisite rehab shuffle, came back stronger, tougher, and more successful. In 2007 she debuted her own line at Topshop. I was there at the launch, to witness the doors being ripped off the shop on Oxford Circus; proof that Kate’s presence, and the thought that they might own a piece of her, turns teenage girls into gorillas.

Between 2011 and 2106 she was married to Jamie Hince, of the indie band the Kills. They lived between Highgate (in a house once occupied by Samuel Taylor Coleridge) and Gloucestershire. If the press coverage from the time were to be believed, their lives were a constant parade of “exclusive” parties and “exotic” holidays, but a quick scan of the international women’s glossies, where her ubiquity in editorial fashion stories and advertising spreads continues, testifies to her continuing commitment to her work.

What else do we know about Kate? We know about her enthusiasms: for clothes; music; photography; travel; parties. We know about her friends, the circle of intimates who have been with her through all the above, the habitués of the haute bohemian London social scene.

We know a little of what she is like in person, off guard, from reports and, in my case, (limited) experience. As I say, I have chatted to her on a number of occasions over the years – when I’ve been able to untie my tongue – and we exchanged pleasantries on the day of the Esquire shoot when she could hardly have been more pleasant and professional. So I can tell you that, for all that she can appear intimidating at first, insulated as she is by her cool, encased as she is in her fame, she also has the ability, winningly, to puncture her own protective layers, with her filthy Croydon cackle – perhaps her most marked characteristic in the flesh – and her silly, salty sense of humour. In other words, whenever I’ve met her I’ve found her friendly and fun. As somebody else once said, like all the best people Kate is well mannered and badly behaved.

As to what Kate thinks, or how she feels about things, I couldn’t tell you. What are her hopes and fears? What makes her laugh? What keeps her awake at night? These details she has chosen not to share with her public. (I asked for an interview, of course, and was turned down flat, of course.)

Kate Moss does not Tweet. Or Instagram. She is not on Facebook. You’ll search in vain for her profile on LinkedIn. She doesn’t want to “connect” with her “audience”. There’s no reality show in the pipeline. You’re unlikely to see her yacking it up on Graham Norton’s sofa. Occasionally a charity appeal may prompt her to pop up in person to say a few words, or a TV commercial may require her to speak some scripted lines. But for the most part she has operated on the simple principle of keeping her trap shut. Never complain, never explain: a mantra passed on to her by Johnny Depp. All of which has served her well. She is a mystery, an enigma, and that’s just how she likes it.

In 2012 she published a coffee table book, Kate: The Kate Moss Book, in collaboration with her friends and colleagues Fabien Baron, Jefferson Hack and Jess Hallett. A substantial, 450-page, £50 hardback, it is a survey of her work to date. Within its pages she is depicted as virgin, whore, saint, sinner, pixie, cowgirl, showgirl, dominatrix, housewife, exhibitionist, outlaw, casualty, royalty, punk, biker, smoker, beach babe, as well as Eve, Marilyn, Bardot and Bowie, among others. Tellingly, she says her favourite photo of all is one by Juergen Teller, a previously unpublished shot from 1998. Grainy, overlit, it shows her in bed, without makeup, her face poking out of the duvet, died pink hair splashed across white pillows. It’s one of the few photos in the book in which this most method of models is playing herself, rather than a part. “It’s kind of rebellious to be yourself,” she notes elsewhere.

In her introduction to Kate, summarising her attitude to her work, and to life in general, she says: “I remember my mum telling me that you can’t have fun all the time, and I still hold my answer true today when I told her, ‘But, why not?’”

This is why Kate Moss matters, to me anyway, beyond the high-fashion gloss and the tabloid smudge. She matters because she stands for something. She matters because her continued flourishing, her extraordinary success, her hold over men and women, young and old – young women even more than old men, it should be said – all of this is a source of teeth-gnashing frustration to the forces of conservatism, who would have women in the public eye be meek and dull and respectable, who would have us all be meek and dull and respectable. She matters because she is a sharp corrective to the joyless, health and safety obsessed, mind-your-p’s-and-q’s rectitude of the moral majority. The people who want to stub out fun.

Make no mistake, thrill seekers: we live in prurient, illiberal times. We are governed by fulminators, spied on by censors, poked and prodded by the purse-lipped and the puritanical, disapproved of by the bastard pitiless busybodies, to quote Rooster Byron, disreputable hero of Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem. (That’s Rooster, by the way, who “can’t be with us on account of the fact he’s in Barbados this week with Kate Moss”). In reaction to this climate of enforced conformity, unlike Kate and Rooster we are mostly cowed and compliant. Our nation wears a fleece for comfort and shines its shoes for special occasions. It watches its waist line, moderates its intake, gets up early, puts the hours in, then collapses in front of the telly, ready to be outraged, and to condemn.

But each generation produces those, famous and otherwise, who operate outside the narrow margins of the acceptable, unbound by red tape, off-grid and unashamed. Men and women who behave as we would wish to in our wilder imaginings, if only we were braver, freer, more talented, sexier, not so safe and square.

Of her pronounced rebellious streak, Kate says, in her book: “It has given me a kind of strength. I know I’m supposed to give a fuck, but I don’t care.”

As she gets older there will be attempts to tame her, to bring her into the fold, give her national treasure status, maybe even a pin-on badge from the government for services to fashion. Well, why not? But I hope they don’t succeed in blunting her edges, in making her reverent. She’s our spirit of revelry, of mischief and merry-making, and while her day job may see her in the service of the megabrand conglomerates, shilling for mobile phones or nail varnish or fake tan, her most important and enduring role is as the girl who doesn't give a fuck. Sunglasses on, head down, nose wrinkled, incisors at the ready, Kate Moss is the girl for us. Always has been, always will be.