A September morning in Dagenham, where east London edges into the Essex hinterland. Roundabouts, bus shelters, roadworks. Shopping parades offering ready-made narratives: take-away, pharmacy, funeral director. Rows of houses putting brave faces on it. Weather that can’t make up its mind.

Outside the Sydney Russell School on Parsloes Avenue, two small groups have assembled. A soundbite of news reporters. A ribbon of local worthies. And, in green blazer and yellow polo shirt, a teenage boy who has been selected from among more than 2,000 students to welcome today’s special visitor.

Word goes round: he’s only five minutes away. A respectful hush. A shuffling of feet. Right on time, from the direction of the staff car park, he approaches. Blue suit, white shirt, black shoes. Short grey hair persuaded into a parting from which it may never return. He’s accompanied by a woman in an assertive pink blazer. They stride just a little self-consciously across the Tarmac, pleased-to-be-here grins fixed in place.

“You said ‘Come back!’” he says. A greeting he may have prepared earlier. (He first visited in 2021, to observe the school’s post-lockdown reopening. Now he is honouring his promise to return.) He processes along the line, shaking hands, offering words of encouragement and gratitude. Having observed this ritual, we move inside, day passes stickered to our chests, overseen by a brace of police protection officers.

The Right Honourable Sir Keir Starmer, Leader of the Labour Party and of His Majesty’s Opposition since 2020 and, according to all polls, Britain’s Prime Minister-in-waiting, is a solidly built 61-year-old white man with the purposeful stride and plausible manner of a senior manager. Which is, in a way, exactly what he is. If Starmer in person projects anything you might not catch in his not-always-scintillating media appearances, it’s an intense focus. He’s business-like. He’s competent. He’s on message. To his detractors, this is his curse: he’s too serious and insufficiently charismatic to be Prime Minister. To his boosters, it’s his gift: he is serious, as he should be in his position; he’s dignified, because that’s what’s required. He’s not just here for the photo op. He’s not interested in fame for its own sake. He’s here to fix things, to make a difference. (He’s also here for the photo op.)

“I get a little bit irked when I hear stuff about how he’s so serious,” Parvais Jabbar, a close friend of Starmer’s, tells me. “That’s not my experience. In private he’s an incredibly fun person to be with. But, at the same time, what I want, and I’m sure what a lot of people want, are serious people in government. And I think if he had to choose, he’d prefer to be called serious than to be seen as a good laugh.”

In the New Statesman, august journal of the progressive left, in the week of Starmer’s visit to Sydney Russell, Andrew Marr, the veteran political journalist, publishes a column under the headline, “The Starmer Conundrum”. “Who is he, really?” asks Marr. “What, fundamentally, does he stand for? For a private and unrhetorical man, these are uncomfortable questions.”

The answers matter, in Marr’s analysis, because to win a majority at the next general election, Starmer “needs to be better understood, better liked”.

Perhaps most adults, in a school setting, take on a slightly teacherly aspect. At Sydney Russell, watching Starmer answering students’ questions and offering advice, one can’t help speculating that were his host for the morning, the school’s principal, Mrs Cross (she’s actually very smiley), to decide to move on, Starmer might make a decent replacement. He wears his authority lightly but firmly. “Fantastic!” he says — a frequent word of approbation — when apprised of the school’s various achievements.

The woman in the pink blazer is Bridget Phillipson, the shadow education secretary. Unlike her boss, whose accent — pegged as “classless” by Marr, not inaccurately — betrays little of his background, when Phillipson speaks no one is in any doubt of where she comes from. She grew up in Sunderland, in circumstances every bit as challenging as those of many of the kids who attend Sydney Russell, which draws its intake almost exclusively from surrounding council estates. (We are in the constituency of Dagenham and Rainham, a resolutely working-class area and a Labour seat since its creation, though only narrowly held at the disastrous — for Labour — general election of 2019.) Like her boss, Phillipson has risen to a leading position in British public life without many, or any, of the advantages that so often ease the paths to power of our most senior politicians, especially those of the successive Conservative-led administrations that have been in government since 2010. The difference is, with her you can tell pretty much immediately; with Starmer it’s less obvious.

Today, Starmer and Phillipson are in Dagenham to help promote one of the key skills they believe working-class kids have traditionally been denied: “oracy”, the ability to speak confidently in public. The organiser of the morning’s activities is a non-profit, Debate Mate. Starmer is photographed in front of a Debate Mate slogan: “Learn Today. Lead Tomorrow.” We make a dash upstairs to a classroom where two teams of teenagers will debate today’s proposition: this house would prioritise the environment over economic growth. Starmer and Phillipson will offer advice and adjudicate.

They take their seats with the first team. Starmer gets straight to business. What is the most important point they hope to land? How can they anticipate what the other side will say in return, and what will be their response? Before he entered politics, Starmer was a barrister. He has sometimes been accused of being too lawyerly in his public statements — dispassionate, equivocal — but here his earnestness is a good fit. He takes his task seriously. This is important to him.

The debate begins. The first young person to speak is a natural performer. Others are more hesitant, understandably so given they are in the position of being filmed for local TV while members of Parliament, and assorted strangers, and, doubtless infinitely worse, their classmates, look on. Throughout, Starmer scribbles notes in ballpoint on scraps of paper, circling certain words and phrases, underlining others.

When it’s his turn to speak, Starmer praises the students’ tactics and techniques, their body language and use of eye contact (“Fantastic!”) and their ability to make cogent arguments under pressure. The result: Team Environment wins over Team Economic Growth. Starmer betrays no hint of which side of the argument he favours himself. Instead he stands around chatting with members of staff and the Debate Mate team, offering more words of approval, agreeing about the importance of their work.

Who is Keir Starmer, really?

Perhaps we’ll find out back in the lobby, where another group of students has assembled. They take turns to ask him questions. About the benefit cap on families that have more than two children, which Starmer has said he would not scrap if elected. The cost-of-living crisis: “The number-one issue facing the country,” he says. Fair pay for NHS workers, which he would fund by eradicating tax breaks for non-doms. His messages are of unity between opposing factions. “We need to stop dividing people,” he says. He is asked about Net Zero targets, and why he is sceptical about ULEZ, the (Labour) Mayor of London’s crackdown on the most polluting cars.

He says that he has kids their age — a 15-year-old son and a 12-year-old daughter — and he doesn’t want them growing up in a city choked by exhaust fumes, any more than any parent would, but he worries that some people are unfairly penalised by the ULEZ expansion. (He doesn’t say he worries that ULEZ is a potential vote-loser, as identified at Labour’s by-election loss in Uxbridge, last July.) “What do you think?, he asks his interrogators.

Relaxed and expansive while talking to the kids, one can see him visibly stiffen as he moves on to his next task. I stand behind the TV and radio people as he submits to their questions.

After a cursory opener about his reason for being in Dagenham — an exchange that one suspects will not make the lunchtime news — we turn immediately to the great matters of state, the existential questions facing the nation. Yeah, right. Instead, Starmer is asked about issues of fleeting concern that dominate this morning’s headlines. He becomes clipped and circumspect.

A civil servant has, allegedly, been caught spying for China. Should we sever diplomatic ties? “China is a strategic challenge, that’s for sure,” he says. “What we need is a policy that is clear and settled, and we haven’t had that. We’ve had division and inconsistency.”

An 11-year-old girl has been savaged by a dog. Should the American Bully XL be added to the banned-breeds list? “I think there’s a strong case for banning this particular breed. Let’s hear what the government has to say…”

What about the RAAC scandal (Reinforced Autoclaved Aerated Concrete, if you must know), and our crumbling schools, of which Sydney Russell, as it happens, is not one? “I think this issue of crumbling buildings is a metaphor for this crumbling government…”

Would education be a priority for a Labour government? (Starmer enjoys a football analogy; this question is what you might call an open goal.) “Education would be a huge priority for an incoming Labour government. Just as it was with the last Labour government.”

Aha! The last Labour government. 1997 and all that. Blair and Brown. New Labour. Centrism. (Has he fluffed it?) Starmer is reminded that Sharon Graham, general secretary of the Unite union, recently warned that Labour was in danger of becoming a “1990s tribute act”. What does he say to her?

“We are looking to the future, not the past,” he says. He begins to talk about growing the economy, and dignity and respect for working people, but then he’s interrupted by a fire alarm. No problem, it’s just a test. He waits, starts again. “the Labour Party is absolutely focused on the future and not the past, and the challenges we will inherit if we are privileged enough to go into government. The central challenge will be growing the economy.” Then more on respect and dignity for working people. He says that his government would be “mission-driven”. That it will “fix the fundamentals.” He talks about “smashing the class ceiling”.

A reporter for LBC, perhaps feeling we’ve had quite enough of all that, would like to return to the issue of dangerous dogs. Would Starmer be happy to see an American Bully XL living on his street? The alarm goes off again, as if God were throwing him a bone.

Do Starmer’s attentive blue eyes betray the occasional flicker of impatience as he goes about his business as Leader of the Opposition and instant expert on all things under the sun, from international diplomacy to the canine menace? Now that it’s my turn to quiz him, should I ask him about the American Bully XL, just to see if I can penetrate his unflappable façade, get him to snap, tease out the real Keir Starmer? (Would he be happy to see an American Bully XL living in his house? How about sleeping at the foot of his bed? Would he like to see an American Bully XL living on Sharon Graham of Unite’s street? Would he agree that alleged Chinese spies should be dealt with by locking them in crumbling schools with only American Bully XLs for company? Or would he prefer to hear first from Rishi Sunak on these questions?)

An office at the school has been set aside for our interview. The pair of us take seats at a conference table. Starmer is pressed for time (I am assured that he is always pressed for time) so I get straight to it. Why is oracy important? I, too, can do cursory questions, although it seems like a good place to start, because Starmer is himself proof that social mobility exists in Britain. Or, at least, that it existed when he was a boy.

“That may be why I feel so strongly about it,” he says. “That progress has been the story of my life. I was lucky to have the opportunities I have had.

“It is shocking,” he continues, “that too many children’s futures are determined by how much their parents earn, rather than their own talent and ability.

“What drove my parents,” he says, “what comforted them, even, was this belief they had that the next generation, their kids, would get a better chance than they had. That is the story of my life but it shouldn’t be an exceptional story. It should be so commonplace that you don’t have to interview me about it. My story should be the everyday story.”

Who is Keir Starmer, really?

He was born in south London and grew up in the small town of Hurst Green, on the Surrey-Kent border, the second of Rod and Josephine Starmer’s four children: two boys, two girls.

“We were in a pebbledash semi, with not very much money,” he says. “My dad worked in a factory as a toolmaker. My mum was a nurse.”

Starmer shared a small bedroom with his older brother. They slept in a bunk bed. It was, he says, “a classic working-class upbringing”. Only with the terrible complication that his mother was seriously unwell. “She had this awful Still’s disease when she was young. And, essentially, after she had children, she never went back to work.” Still’s is a rare and debilitating auto-inflammatory disease that causes fevers, severe pain and a distinctive rash. Over time, the body shuts down completely.

His mother’s illness, and its effect on her, and on his father, and on him and his siblings, is the central story of his young life, and it continues to inform everything he thinks and feels.

“I think there’s no doubt that he’s driven by his background,” says Parvais Jabbar. “We’ve talked about his childhood and his parents. He’s this hard-working lawyer, but he also had to make sure his siblings were OK, his parents were OK, his mother was OK. He was always the person doing the looking after.”

For all the supposed enigma of Starmer, it’s not as if he hasn’t spoken about plenty of this before. Much as I would like to claim a scoop, I’m hardly the first journalist to get him to open up about his past. In TV and radio interviews, in newspaper profiles, he has discussed his early years and experiences. With me, he is more expansive when talking about his parents than on any other topic. It’s another thing that frustrates Jabbar.

“People say, ‘We don’t know the real Keir; we don’t know his background,’” says Jabbar. “But I’ve seen many pieces where he talks about his background! And then they say, ‘Oh, well, that’s all very interesting, but we want to know what his policies are…’”

At the risk of repeating those earlier articles, I ask Starmer to tell me about his father, who died in 2018. How does he take after him? How do they differ? He speaks for a long time without interruption.

“My relationship with my dad can only be understood by describing his relationship with my mum,” he says. “My mum was very ill most of her life and periodically would be rushed into hospital, into high-dependency units. And more often than I care to remember it was a bit touch and go as to whether or not she would make it. My dad was totally committed to her.” He says it again, for emphasis. “He was totally committed, in every conceivable way. Learnt every symptom, learnt exactly what needed to be done in any situation. And if she was in hospital, he’d be with her and he’d stay with her, sleeping on benches in the corridors if necessary, until she came home. And that was his absolute focus, and everything else was secondary to that to that devotion and loyalty and incredible love for my mum. And that left little space…”

He pauses, briefly. “I mean, I’m only seeing this after the event, if I’m honest. I’m not going to pretend I was seeing all this growing up. But it left little emotional space for the rest of us, because it was all invested in my mum. I don’t resent that, it’s just an observation. And therefore, my relationship with my dad was more distant and lacking some of that bond that he had with my mum.”

He returns to the question. “So, what do I take from my dad? I take that sense of loyalty, commitment to somebody else: my mum. The other thing I take from my dad, something I’ve reflected on more and more, is the fact that because he worked in a factory, he felt disrespected. He felt looked down upon. We’ll all have had those situations where a number of adults stand around and the conversation is, ‘What do you do for a living?’ And my dad hated that conversation, because he knew that when he said, ‘I work in a factory’, there’d be a sort of silence where nobody would quite know what to say next. He hated it, and it caused him to sort of withdraw.”

Rod Starmer maintained a punishing routine: “He worked from eight in the morning until five o’clock in the afternoon, when he would come home for his tea, then go back to work at six until 10, Monday to Friday.

“But that disrespect he carried with him all his life. And that’s why ‘respect’ is such an important word for me. Can you look somebody in the eye and really say you respect them? And for an incoming Labour government, how do you enhance the dignity and respect of every single person? That I take from my dad.”

He hasn’t finished. “You can’t divorce that from my mum because my mum was… the two of them, Rod and Jo. You could never have Rod or Jo, one without the other. They were so bound together. She was incredibly courageous. She had challenge after challenge thrown at her. She was told, when she was 11, you won’t be walking by the time you’re 20 and you certainly won’t have children. She was determined that both of those things would be proved wrong, and she was assisted by some brilliant consultants at Guy’s Hospital, and she had four children and she built back up and walked over and over again, every time she had an operation. And she never moaned about it. If you ever asked my mum, ‘How are you?’ she’d say, ‘I’m alright, how are you?’”

Jo Starmer’s battle with Still’s ended in harrowing circumstances. “In the end,” her son says, “she couldn’t really move any of her limbs or do anything very much unsupported. And then she stopped speaking. Her leg was amputated, and so this lifelong determination to walk ended. And that broke her, to an extent. The last years of her life, when she was in that state, broke her.

“I regret very little in life,” Starmer says, “but I do regret the fact that, by then, we had two very young children, and they never got to know my mum, because she couldn’t communicate, she wasn’t walking, so they never saw for themselves the warm, loving person that she was. And I said this at my dad’s funeral: three years after she died, he died, but he actually died of a broken heart when my mum died, because their reason for living was each other.”

He looks wrung out after saying this, and I tell him I’m sorry.

“Well,” he says, “I’ll try to pull myself together and go on with the interview.”

It must have been incredibly difficult for him, as a teenager, having to cope with such extreme circumstances?

“Formative as well, though,” he says, regaining his composure. “There are challenges in the job I’m doing, and every time there’s a challenge I do think of my mum and dad, I think about the respect for my dad and the courage of my mum, and part of me thinks if my mum can get up and walk after everything that was thrown at her, I can go and do whatever it is I have to go and do. You do carry these things with you, I think.”

His parents named him after Keir Hardie, the Scottish trade unionist, one of the founders of the Labour Party and its first Parliamentary leader, from 1906 to 1908. “I can’t claim any credit for that,” he says. A line he may possibly have used before.

We don’t often imagine Surrey as a hotbed of socialist radicalism, but Starmer grew up in a rural community, not on a private estate of McMansions: the popular image of that county as the gold buckle of the stockbroker belt.

“Surrey is predominantly Tory,” he says. “I’m not going to pretend that there isn’t a good deal of wealth. A lot of people there have made a really good living for themselves, and good luck to them. But as with all rural communities there is also poverty. It’s a misunderstanding about the countryside that it’s only those who are better off who live there. It’s not the case and it wasn’t the case.”

The Starmer home was “a Labour household, there’s no doubt about that. And probably for that reason I joined the Labour Party at the first opportunity.” At 16, he became a member of the East Surrey Young Socialists. “Unfortunately,” he says, “it only had four members.”

He was educated at the selective Reigate Grammar School. In addition to his academic success, he played football and excelled at music, attending classes on Saturday mornings at the prestigious Guildhall School of Music, in the City, as a scholar. “I played with people who were naturally exceptional,” he tells me. “I worked hard, but I could never quite match their level.” He studied violin alongside Norman Cook, later Fatboy Slim, who was a couple of years above him at the Guildhall, and he walked out to “Right Here, Right Now” at the Labour Party Conference in 2021, pleased to be able to acknowledge the success of an old contemporary.

Starmer is sometimes dismissed as a technocrat, but he comes across as someone at least as engaged with the arts as the sciences. “Frankly,” he says, “I do think that we have lost sight of the value of art and of music in learning in our education system. I’m determined to change that. Not just because I did it and I know how powerful it can be, but because of the key life skills it teaches: confidence, creativity, discipline.”

He read law at Leeds University at the urging of his parents rather than out of some youthful lust for courtroom drama. “They said you need to go and get yourself a decent, stable job. And [being] a lawyer is a decent, stable job.” So off he went. “I’d never met a lawyer when I got to university. I don’t think I’d completely worked out in my head the difference between a solicitor and a barrister. So I was on a pretty steep learning curve because I rubbed up against people in year one whose parents were lawyers, and they knew very well where they wanted to go, and they had that confidence.”

He was the first person in his family to attend university and the only one of Rod and Jo’s children to do so. His siblings did not follow him into middle-class professions. They work as a mechanic, a carer and a dinner lady. His claim to understand the challenges facing what he calls “working people” is not an empty one.

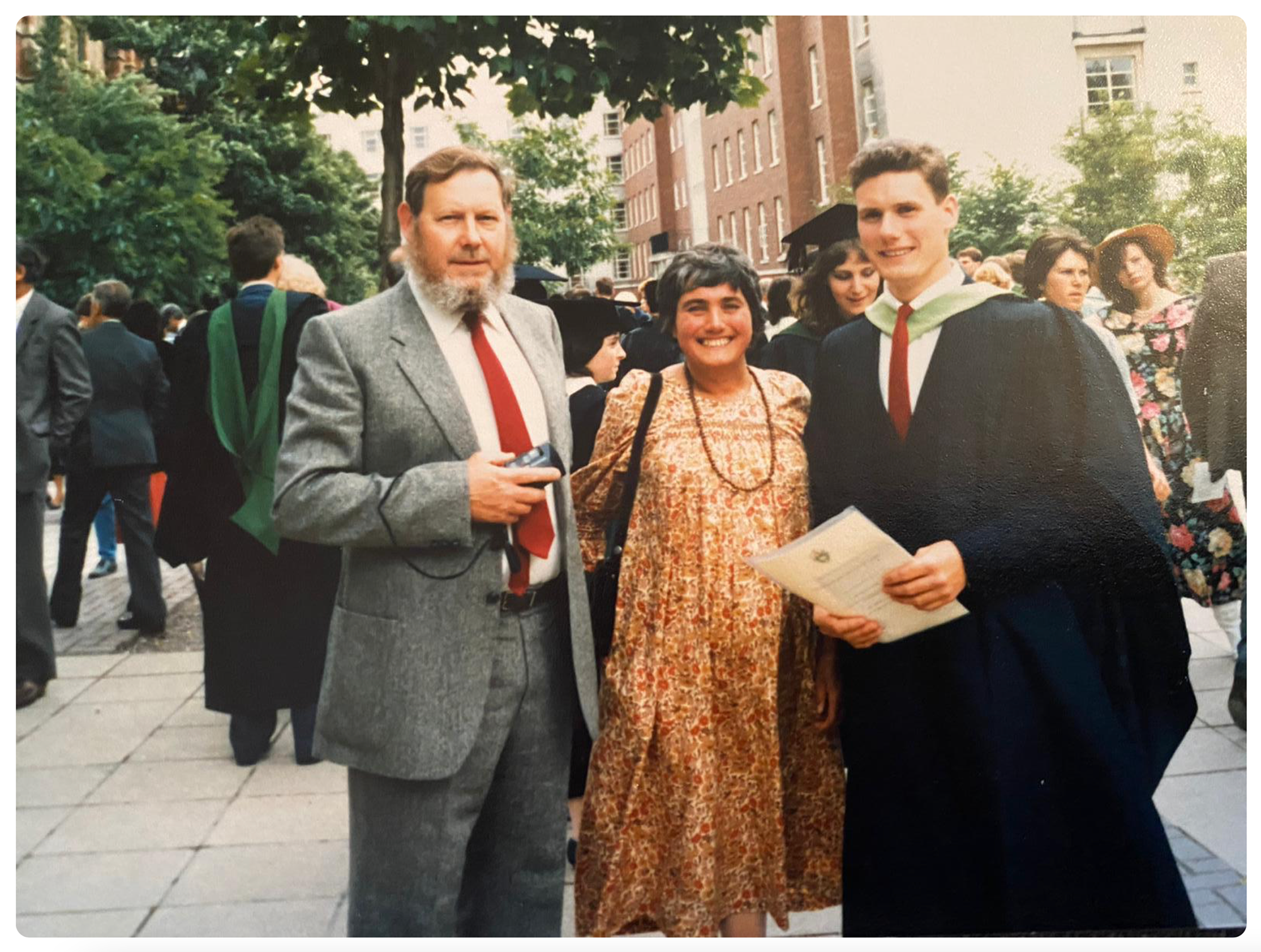

He graduated from Leeds in 1985 and spent a year at Oxford as a postgraduate, before he was called to the Bar and began his career in criminal-defence work, specialising in human rights.

He had not lost his adolescent idealism. In 1986 and 1987, he edited a magazine, Socialist Alternatives, an attempt to marry left-wing ideals with feminism and the green movement. He wrote about the printworkers’ strike at Wapping, and he interviewed Tony Benn, the longtime hero of the Labour left. “Like most people,” he told he told Lauren Laverne on Desert Island Discs in 2020, “I started off as the radical who knew everything. I’m now much more open to ideas…”

He lived in a shared flat — “messier and more chaotic than my current home” he tells me — above a massage parlour on the Archway Road in north London, and while he has spoken in the past of a period of late nights dancing to Northern Soul records (he chose Dobie Gray’s Northern classic “Out on the Floor” as one of the tracks to take to his island) and remembers enjoying himself “sometimes a bit too much”, the sense one gets is of a young man in a hurry to get on. He worked hard. On one occasion, so absorbed was Starmer in his work that he remained in his room, oblivious, while burglars entered the flat and made off with the television.

In 1990, still in his twenties, Starmer was a founder member of Doughty Street Chambers, the pioneering and disruptive law firm that became home to eminent, crusading lawyers including George Robertson, Helena Kennedy, Edward Fitzgerald and Amal Clooney.

It was in that period, almost 30 years ago, that he met Parvais Jabbar, now the co-executive director of The Death Penalty Project, which provides free legal representation to death-row prisoners around the world. They’ve known each other for almost 30 years.

“He was a super-dynamic junior barrister,” Jabbar tells me on the phone. “And, from the beginning, really hard-working and incredibly passionate about human rights. Imagine: I’m asking someone to take on a case. I’m not paying them. It’s pro bono.

“When a warrant of execution has been issued,” Jabbar says, “and it’s a Thursday, and somebody might be executed on the Monday, what you need is somebody you can go to who can work on the case through the weekend. The idea that you can ring someone at any time, day or night, and say ‘I need your help,’ that is immeasurable. And that’s what Keir would do.”

Jabbar calculates that over two decades Starmer probably devoted up to 70 per cent of his time to unpaid, pro bono work. “That’s a significant amount of time to give up to human-rights cases where you’re not making any money,” he says. “I mean, we all need to earn money! But the one thing he never ever said to me or to anyone who works with me was, ‘Sorry, no, I’m too busy, I’d love to but I can’t do it.’ For two decades, he never said no. So there’s a drive there.”

The two men became friends away from work, sharing family holidays, going to football together. They still meet for coffee or a drink whenever they can — which is less frequently, Jabbar says, since Starmer became Labour leader.

“It’s a very privileged and fortunate scenario when you actually really get on with the people you work with,” says Jabbar. “When you’re travelling, visiting clients on death row, meeting lawyers, if you’re with people you’re not really close to, you really just want to go to your hotel room in the evening and have a break. But we would have dinner, have drinks. And I think that helped the work as well. It wasn’t a Monday-to-Friday thing for me. It’s 24/7. And the same for Keir. It’s not a single case. It’s an issue.”

Starmer and Jabbar worked on what Starmer calls “strategic litigation”: seeking to change the laws of countries in the Caribbean and Africa, former British colonies where the final court of appeal is the Privy Council in London.

“When you start as a lawyer, you do individual cases,” Starmer explains. “That’s the nature of the beast. I became quickly frustrated with litigating the same case over and over. Whether it’s a health-and-safety issue in a particular factory, where an injury happens and then another and another, or even the death-penalty cases where you’re representing a specific individual. Can we not take on the whole issue on behalf of a number of people in one go? That’s how we handled the death-penalty cases in particular: what are the landmark cases that will change the position of everybody who finds themselves on death row in the Caribbean?”

In the UK, most famously, Starmer defended the Greenpeace campaigners Helen Steel and David Morris in their battle against McDonald’s. The McLibel case, as it became known, was the longest trial in English legal history. Again, Starmer was working pro bono. Later, he advocated against the Iraq war on the grounds that it was illegal under international law. He advised the Northern Ireland Policing Board, in the wake of the Good Friday Agreement’s abolition of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, on how to put together a non-sectarian police force that would be human-rights-compliant.

“That was very uplifting for me,” he says. “And a real turning point in my career. I was going from a lawyer litigating on the outside to somebody changing the institutions from within.”

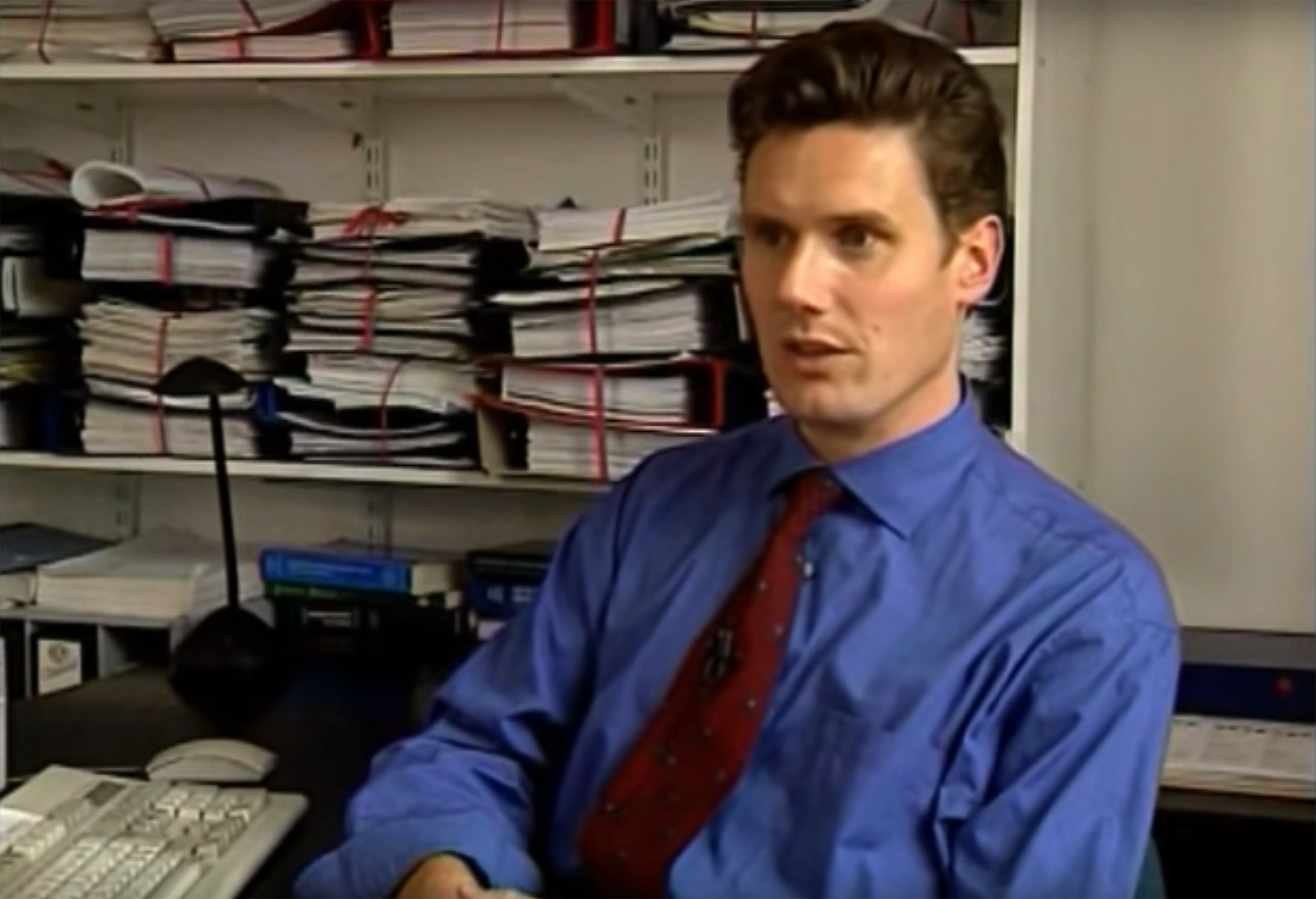

In 2002, Starmer was appointed a QC (now KC), in recognition of his work. Six years later, in a move that surprised many in the legal world, he was appointed head of the Crown Prosecution Service and Director of Public Prosecutions. It was a spectacular case of poacher turned gamekeeper, the left-wing public defender now the most powerful prosecutor in the land.

“Suddenly I had 7,000 staff across England and Wales and millions of decisions to make,” he says. “That was a game-changer.”

At the conclusion of his mandatory five-year term, he was made Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath: Sir Keir Starmer. But if the working-class outsider was now a pillar of the establishment, a man at the summit of his profession, he was about to start all over again.

“The only way you can really change things to improve the lives of working people across Britain is to get into politics,” he says. “I didn’t plan years ago that I would become an MP. But I got to the point in my own career and life that there was no other way.” In May 2015, he stood for Parliament, and won.

It’s unedifying, no doubt, to have to clamp our toxin-repelling masks over our heads and snorkel once again through the effluvia of the past eight years of British politics, but it helps to give some context to Starmer’s rise from rookie MP to potential PM, and perhaps a sense of how far he has moved Labour already, in his three years as leader, from repeat electoral flops to pollsters’ favourites to form the next government.

By the time he arrived in Westminster, Starmer was 52. “Late in the day,” he concedes. The new MP for Holborn and St Pancras in central London joined a Parliamentary party in disarray. David Cameron’s Conservative Party, which had governed for the previous five years in coalition with the Liberal Democrats, had won a narrow majority over Ed Miliband’s Labour.

Miliband, a wonkish creature, frequently pilloried for his awkward attempts not to appear strange while doing things that come relatively naturally to the rest of us (eating a sandwich), as well as his resemblance to a Claymation cheese-fetishist (Wallace, of …and Gromit fame), stood down as leader and the party elected in his place the previously inconceivable figure of Jeremy Corbyn, for decades a fringe figure on the far left of the party. Labour had gone, in a few years, from a smoothly telegenic statesman — whatever one thinks of Tony Blair, he was eminently electable, as he proved in 1997, 2001, and 2005 — to a megaphone-wielding, street-corner agitator. It was as if Private Eye’s bearded Bolshevik, Dave Spart, had somehow wrested control of the party leadership; 1990s New Man giving way to 1970s Old Man.

Corbyn was a divisive figure, within and without his party. Those who had supported New Labour in the 1990s and 2000s — the centre-left — were perhaps especially dismayed by his elevation.

For an Esquire cover story in 2016, at which time Corbyn was newly ensconced in the Labour leader’s office, I spent some time with Tony Blair. Among many things, we talked about how the leadership of his party had been captured by the hard left.

“This is not about Jeremy Corbyn,” Blair said. “It’s about two different cultures in one organism. One is the culture of the Labour Party as a party of government. And that, historically, is why Labour was formed: to win representation in Parliament and ultimately to be the government of the country. The other culture is the ultra-left, which believes the important thing is to raise the consciousness of the people, that the action on the street is as important as the action in Parliament. It’s a huge problem because they live in a world that is very, very remote from the way that the broad mass of people think.”

Blair predicted, correctly as it turned out, that Labour under Corbyn could not win a general election. “Not because they’re too left,” he said, “or because they’re too principled. It’s because they’re too wrong. The reason their policies shouldn’t be supported isn’t because they’re too wildly radical, it’s because they’re not. They don’t work. They’re actually a form of conservatism. This is the point about them. What they’re offering is a mixture of fantasy and error.”

Not a ringing endorsement, then. (You should hear what Corbyn says about Blair.)

Starmer had only been in Parliament for a year when David Cameron resigned as PM, on the morning the result of the Brexit referendum was announced. In one of the most spectacular miscalculations in British political history, Cameron had included the referendum in his election manifesto: a doomed bid to unify his own party. He favoured Remain, while Boris Johnson, his school chum and university drinking buddy, fronted Vote Leave. Leave won. The perennially harried Theresa May won the Tory leadership election and became Prime Minister. Her principal task: to make a deal with the EU that would take Britain out of Europe, even though she, like Cameron, had favoured staying in.

Just six months into his Parliamentary career, Starmer had been appointed shadow minister for immigration by Corbyn. Within a year he resigned, alongside scores of his colleagues, in protest at Corbyn’s pallid performance during the referendum. Apparently undiscouraged, Corbyn won the resulting leadership election, his second, and Starmer now accepted a front-bench post, as shadow secretary of state for exiting the European Union: a crucial role as Labour’s spokesperson on the most significant topic of the day. At this time he advocated a second referendum — in which he would vote Remain.

The leaders of both the main parties seemed unable to unite their own front benches, let alone their parties. In 2017, May called a snap general election, hoping to strengthen her hand in Brexit negotiations. She weakened it: the Conservatives won the popular vote, but their overall majority was eradicated. Labour gained 30 seats, better than expected, but the party had lost again: three consecutive general elections on the bounce, as they say on the football phone-ins.

May struggled on through two votes of confidence but left in tears in May 2019, knifed in the front by her own colleagues, in classic Conservative style. She was succeeded, incredible as it seems now (and in fact seemed at the time), by Boris Johnson, who took the Tories into the 2019 general election with a simple promise: get Brexit done.

And so a party led by an unprincipled after-dinner clown faced off against a party led by a humourless rabble-rousing idealogue, both bristling with animus. The centre had not held. The culture wars raged. As the decade ended, Britain appeared more polarised than at any time since the Thatcherite 1980s, maybe more so. And, just as they had in the 1980s, Labour lost. Again. It was the party’s worst showing at the polls since 1935. Corbyn announced he would step down following the election of a new Labour leader.

Even after he was appointed to the shadow cabinet, friends suggest, it’s likely Starmer hadn’t previously seen himself as a frontrunner for the leadership of the party. Most likely he imagined himself a potential Attorney General or Minister of Justice in a Labour government of the future, positions that would have drawn directly on his legal knowledge and experience.

“He phoned me up,” says Starmer’s friend Jabbar. “I remember having the conversation with him. ‘There’s a leadership election. Some people are asking me to stand. What do you think?’ I said, ‘I absolutely think you should. What do you think?’ And he said, ‘I think I have to, because I’m being asked to, and it’s an opportunity to make a difference. It wasn’t, ‘This sounds fantastic! I’ll be leader of the Labour Party!”

Starmer won the vote in the first round, under the slogan “Another Future is Possible”. He became leader in April 2020, in the teeth of the first pandemic lockdown. He was in a ticklish position. At a moment of national emergency, Starmer’s job, in public, was to rally behind the government. In private, it was to try to unify the radical and moderate wings of his party.

The Covid crisis would have caused epic difficulties for any government, but Boris Johnson, once he’d recovered from his own death’s-door hospitalisation, seemed uniquely ill-equipped to cope with it. Despite the lockdowns, and the vaccines, and Dishy Rishi’s various strategies for keeping the economy moving (remember Dishy Rishi?), Britain suffered the worst per capita death toll of any country in western Europe. To quote the man who presided, in a manner of speaking, over it all: them’s the breaks.

Wait. I feel there might be something I’m forgetting? Partygate! Another of Johnson’s gift-wrapped contributions to the gaiety of the nation: his repeated flouting of his own social-distancing rules. The concatenation of scandals — the unlawful proroguing of Parliament, the ignoring of allegations of sexual misconduct against Tory MPs, the mass resignations of ministers, a vote of no confidence — would do for Johnson in the end. But not yet.

Starmer is not a career politician. This, one would think, must surely be to his advantage, given how low in the public estimation that category of person has plummeted: “The shallow men and women of Westminster,” he recently called them. He does not pretend to find Parliament especially congenial. And he disapproves of the atmosphere in the lobbies and inside the so-called Westminster bubble.

“I’ve never worked in an environment as bad as Parliament,” he says. “There are far too many stories of abuse of power. In public service, in the civil service, in the private sector, it wouldn’t be tolerated. Most leaders of modern businesses are very thoughtful about their workforce, very thoughtful about what their principles and values are. Parliament needs to be catapulted into the 21st century when it comes to this.”

Six months into Starmer’s leadership, the Equalities and Human Rights Commission published a report into antisemitism in the Labour Party during Corbyn’s time as leader. It found that the party was guilty of unlawful acts of harassment and discrimination. Corbyn said that the findings and the response to them were “dramatically overstated”. Starmer suspended him, and then removed the whip, effectively exiling his predecessor from the Parliamentary party. Corbyn has declined to apologise for his comments, and as a result will not be permitted to stand as a Labour candidate in the next election.

“Sometimes you have to be ruthless to be a good leader,” Starmer told me.

On the phone a few days after meeting him in Dagenham, I asked Starmer if antisemitism still exists in the Labour Party? (This was a month before the present crisis in the Middle East.)

“We have to fight antisemitism every day of the week,” he said, “and whether it’s the Labour Party or any political party or anywhere across the country, I don’t think anyone would claim it has been totally eradicated, unfortunately. What I can say is I made a promise the day I was elected Labour leader to root out antisemitism. And that is what we have done. But we must never relent on that. I always said I would measure my progress not on my own analysis but by looking at whether those who left the Labour Party because of antisemitism felt able to come back to the party. And a number of leading people have now come back, so that’s evidence to me that we’re on the right track.”

Critics and supporters, and even dispassionate observers, agree that Starmer has moved the Labour Party towards the centre ground — how far he’s moved it is disputed, and there are still representatives of the left wing in his frontbench team, but he could hardly have moved it further towards the left — and in the process he has abandoned pledges and policy proposals he stood on at the 2019 election. He doesn’t see it like that. What he is trying to do, he says, is to make the party electable. Some of the traditional socialist ideals espoused by Corbyn, the ideals that Starmer grew up on and ran on in his leadership campaign — nationalising public utilities, scrapping tuition fees, defending free movement within the EU — have been replaced by a series of “missions”: to “secure the highest sustained growth in the G7”; to “make Britain a clean-energy superpower”, to “build an NHS fit for the future”, to “make Britain’s streets safe”; to “break down the barriers to opportunity at every stage”. Noble aims, all. But, as many observers have pointed out, at least initially he will have precious few resources to fulfil them: the cupboard is bare. Funding from private investment and from cleaning up tax loopholes will have to do in place of raising tax rates. The policy specifics, and costings, will come later. In the meantime, Starmer continues his attempts to persuade potential voters, and his own party, that he is the man for the job.

He suffered an early setback in May 2021, when, in a by-election, Labour lost the previously safe seat of Hartlepool to the Tories. An event, he told the BBC’s Nick Robinson, that he felt “like a punch to the stomach”. Much more encouraging news this October, when Labour won three significant by-elections: first Rutherglen and Ham-ilton West, in Scotland; then Tamworth and Mid Bedfordshire, both previously safe Tory seats.

Is the Labour Party united behind him, I ask Starmer? “Yes, it is,” he says, a line that might surprise Corbyn supporters. “It’s incredibly united. And I’ll tell you for why. One: because after losing so badly in 2019, the whole party and movement recognised we had to change. Two: because whatever the breadth of views in the Labour Party, and there are many, and that’s a good thing, the one reason people come into the Labour Party and movement is because they care passionately about politics and they know that the Labour Party was formed for a purpose. It was never intended to be a social club, or a debating society. It was formed for the purpose of going into government and changing the lives of working people.

“And we’ve been able to show that we can change the party and put ourselves in a position where we are credible contenders for the next election: that is incredibly uniting for the party. So, actually, there’s a very strong sense of unity. More than unity, I’d say a sense of purpose.”

In early 2022, as the pandemic began to subside, another crisis: Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Johnson strutted on the global stage, Volodymyr Zelensky’s best bud (peas in a pod: a comedian turned courageous international statesman, and a comedian), but at home his days were numbered. Finally, in July, his fellow Conservatives forced Johnson to resign. Another leadership contest. A new PM: Liz Truss, Thatcherite -slash-Dadaist.

Just days after being introduced to the 15th Prime Minister of her long reign, not as a direct consequence (allegedly), the Queen died. The following day, Truss spontaneously combusted: the uncosted “mini-budget”, the crashing of the pound, the sacking of the Chancellor, the inevitable resignation. Forty-nine days, the briefest prime ministerial tenure in British history and, even her close colleagues seemed to agree, not a moment too short. Gallantly into the breach came Johnson’s former Chancellor and the man whom Truss had recently defeated, Rishi Sunak: the fifth British Prime Minister in just over six years, and the third to face Starmer at the dispatch box, so far. (Margaret Thatcher, Truss’s hero: 11 years as PM, Blair: 10, John Major and Cameron were each in power for six.)

The situation now, a year into Sunak’s premiership: Britain remains mired in the worst cost-of-living crisis for a generation. Wages are low, prices are high. Interest rates have rocketed. At times it feels that those public workers who are not on strike are outnumbered by those who are: transport workers, teachers, ambulance workers, passport officers, air-traffic controllers, the staff of the British Museum, junior doctors, senior doctors… The NHS would be in intensive care, if only a bed were available. And I could go on, but perhaps we’ll leave the further doom-spiralling for another occasion. (Important to have something to look forward to.) Meanwhile, as the Conservative Party conference in October proved, Tory machetes are out again, this time for Sunak, with various right-wing dog-whistlers jockeying for position should the leadership become vacant, chief among them Sunak’s own home secretary, the loveable Suella Braverman, and the aggressively unrepentant Liz Truss. On the plus side: American Bully XLs are to be banned, so that’s one less thing to worry about.

I ask Starmer for his impressions of the Prime Minister. Is it not the case that Sunak is a capable and decent man trying to make the best of a desperate situation?

“In all my dealings with him he’s been perfectly decent,” Starmer says. “But what I would say about him is I think he’s out of touch. I don’t think he really understands what people are going through and that leads him to paint a picture of the country as if everything is fine and nobody’s got any reason to be concerned. That grates with the public because it is so at odds with the lived experience of millions of working people. That’s the first thing. The second thing is I think that he doesn’t have a mandate within the Tory party because he didn’t win the leadership. And so he is accommodating different bits of the Tory party instead of leading from the front. And if you look at the composition of his cabinet you can see that in evidence.”

Most politicians, in public at least, are, to a greater or lesser extent, walking word clouds. They repeat the same focus-grouped phrases and workshopped bullet points in almost every on-the-record utterance. “Dignity” and “respect” are words Starmer returns to repeatedly, along with “change”, which is uttered so frequently you might think he has a mild tic.

“Things Can Only Get Better” was the theme tune the last time a Labour leader overturned a Tory majority at a general election, in 1997. Such has been the souring of the national mood over the past several years that today one wonders if, whatever the outcome of the election, they might get even worse.

“Amongst the things this government has done to people,” Starmer says, “is beaten the hope out of them. Too many people feel that nothing can now be done about that the state of our country. I profoundly disagree, but I can see where that comes from. Or there’s the sense that nothing will be done, because politicians will say one thing and do another.”

It might be unlikely that Labour will lose the next election, but it’s not inconceivable. The ghost at the Starmer banquet is Neil Kinnock, who took a lead in the polls into the 1992 election, after 13 years of divisive Conservative government, and lost to John Major, like Sunak a cricket-loving former Chancellor in charge of a disputatious party — “bastards,” he called his enemies — who was, again like Sunak, widely believed to be too boring to win.

Another football analogy: when a team is ahead in a game, I tell Starmer, commentators talk about parking the bus — don’t do anything rash, play defensively, hold on for the win.

“Nobody’s put this version of it to me before,” says Starmer. “Very good!” He looks genuinely pleased.

“The way I’ve seen it,” he says, “clearly in my mind, is there are three parts to the journey I had to take the Labour Party on, and hopefully the country. The first was to change the party. I believe fundamentally if you lose as badly as we lost in 2019 you don’t look at the electorate and say ‘What on earth were you thinking?’ You look to yourself and say, ‘We need to change and we need to do that first and fast.’ And we didn’t have the right to set out big plans for the country until we’d done that change. Secondly, to expose the government as not fit to govern. Now, the evidence is in abundance. Exhibit A, Boris Johnson. Exhibit B, Liz Truss. Exhibit C, Rishi Sunak. I think many people are beginning to conclude this government’s had long enough now. Third bit, if not them, then why us? That’s the challenge.”

Coverage of Starmer’s speech to the Labour Party conference, in Liverpool, on 10 October, was pushed down the news agenda by the Hamas terror attacks in Israel, and their horrific aftermath. Then, before it even began, the speech was disrupted by a man who rushed the stage and threw glitter over Starmer’s head and shoulders — inviting an off-the-cuff dismissal, which Starmer duly supplied: “Protest or power? That’s why we changed our party.” (“I was not going to let that idiot ruin four years of hard work, and stop me giving that speech,” he told the BBC’s Nick Robinson the following morning.)

The dusting of glitter meant Starmer had to remove his jacket and roll his sleeves up: perhaps not so unwelcome an image for a politician to project while promising to get his hands dirty.

The previous week, during a fractious Conservative Party conference in Manchester, Rishi Sunak had attempted to position himself as the “change” candidate. An ambitious aim, since the Tories have now held power for 13 years, and Sunak himself has been in senior government posts since 2017. His policy announcements — more maths; less smoking; the scrapping of the high-speed railway line, HS2, to Manchester (an interesting time and place for such a revelation) — did not necessarily seem, to some observers, to align with the issues that are being raised most forcibly “on the doorstep”.

Contrasting himself with Sunak — “I never thought I’d say this,” he told the conference, “but I’m beginning to see why Liz Truss won” — Starmer announced a programme of national renewal, the most concrete promise being the building of 1.5 million new homes across the country. Labour, he promised, would have “shovels in the ground and cranes in the sky”. He talked of the cost-of-living crisis “whittling away at our joy”. His own speech he characterised as “a cry of defiance to all those who write our country off”. “What is broken,” he said, “can be repaired.”

If the speech still seemed, to some commentators, light on policy specifics, the change in direction from the Corbyn era was undeniable. Starmer listed the achievements of New Labour with admiration, asserted that “Israel must always have the right to defend her people” — this received a standing ovation from a room that, under Corbyn's leadership, had been filled with Palestinian flags — and hammered home the point about moving Labour from being “a party of protest to a party of service”.

The former New Labour frontbencher David Blunkett recently said that the thing Starmer must supply if he is to win, beyond policies and mission statements, can be summarised in a single word: hope.

Starmer has been seeking advice not only from previous Labour Prime Ministers — he talks regularly to Blair and Gordon Brown — but from successful progressive politicians around the world. He has met twice with Barack Obama, who won the White House with a campaign based around that same freighted word, hope.

Starmer adds a different word: “reassurance.” He says he’s been told he must choose: either hope or reassurance. He believes he must and can offer both. He also says he “prefers to do his talking on the pitch”.

Centrist dad is a pejorative term credited to the Corbynista branch of the Labour Party. Its original use: to describe a certain type of comfortably progressive, insufficiently radical middle-aged man who longs for a return to the New Labour years. At a street party in north London the weekend before our meeting in Dagenham, Starmer briefly, and also perhaps bravely, shared a stage with Centrist Dad, a covers band fronted by Robert Peston, the ITV News political editor; with arts broadcaster John Wilson; and Ed Balls, the former Labour cabinet minister and reality-show contestant, on drums. Among other punk standards, they played “Anarchy in the UK”. No doubt with a certain mordant wit, but possibly you had to be there.

Is Keir Starmer a Centrist Dad? It is foolish to try to predict a person’s politics by itemising their personal lives. There are swivel-eyed right-wingers, one assumes, who, like Starmer, play football, enjoy the music of both Beethoven and Orange Juice and love cooking for their families.

But certainly the details of his home life, his interests and enthusiasms away from work, will be familiar to many readers of Esquire — they certainly chime with me — perhaps more so than the lifestyles of his donkey-jacketed predecessor, or our plutocratic Prime Minister.

Starmer lives in Kentish Town, north London, with his wife Vic, a former lawyer who now works in the NHS as an occupational therapist. (They met-cute. When he questioned some work she’d done on a brief, she is reported to have responded, “Who the fuck does this guy think he is?”) They married in 2007.

He plays five-a-side every Sunday, as he has done since he was a boy. Central midfield. What would his teammates say about him? “They’d say I’m tough in a tackle, and not shy about barking orders,” he says. “They’d also, fairly enough, call me heavily left-footed. My right leg is simply just for standing on.” (“He’s probably not as good as he thinks he is,” Parvais Jabbar tells me, a Manchester United fan getting a little dig in at his Arsenal-supporting friend.)

Starmer is a season ticket-holder at the Emirates. He goes to every home game he can with his son, and sometimes his daughter, too, and they sit in the stands with close friends. “The feeling around the place is something we’ve not had for years,” he says, of Arsenal’s recent title-chasing resurgence under their dynamic young manager, Mikel Arteta. As a fellow leader trying to change the fortunes of a team of previously underperforming reds, does he have any advice for Arteta? “I think he just needs to keep doing what he’s doing,” Starmer says. “But he won’t need lectures from me. I’m all too familiar with backseat drivers giving their unwanted opinions.”

Football aside, his favourite pastime is cooking for his family on Saturday evenings. Starmer is a pescatarian. “I’ve been honing my tandoori salmon recipe,” he tells me. As he chops and stirs, he listens to Craig Charles’s Funk and Soul Show, on BBC Radio 6 Music. (He’s a “6 Music Dad”, another pejorative term, this one deployed to denigrate a stock figure that the Esquire reader, and other groovy cats such as your correspondent, might also consider worryingly close to home.)

Starmer is content — or, at least, prepared — to tell the story of his own childhood, and his parents’ struggles, if it helps explain his character to potential voters. But apart from the basic details above, his private life is mostly off-limits. Since becoming Labour leader, he has managed, so far, to live a fairly normal life, police protection officers notwithstanding. Becoming Prime Minister would change that. Isn’t he daunted?

“I don’t feel daunted,” he says. “But I am worried about my family. I’m obviously alive to the fact that [winning the election would] have a huge impact on all of us. We’ve got two relatively young children. And I will do everything in my power to protect them. That means that at the moment we never name them in public. We never use them for photographs. I want as far as I can to protect their right to be who they are. So I’m fiercely protective of their privacy and of my wife’s.

“That’s why she has never done an interview, never expressed her own views about anything. She loves her job, she loves the people she works with. And so that’s the area that I feel most keenly.”

He prioritises time with Vic and the kids. “On a Friday night it is really rare for me to be doing any work-related stuff after about six o’clock. Vic’s is a Jewish family, so Friday night is a special night and Vic’s dad is often over with us then.” (Her mother died a few years ago.)

He enjoys doing “ordinary dad things”. He thinks it’s important. “I take my son to his sports, take my daughter to her swimming. I’ve met too many people in my life, very often men, who say they wish they spent more time with their kids. And my answer to that is: then spend more time with your kids!”

I tell him that he’ll have to reveal his children’s names if he becomes Prime Minister. “Yes, I think that’s inevitable,” he says. “And also there’ll be more photos of them, because we’re not going to live our lives without our children. So I’m aware that there is that necessary exposure. All we can do is to hold that off as long as possible.”

Will he still be able to go to the football in the way he can now? “That will be much harder,” he says. “So I cherish it even more, game by game.” These don’t sound like the words of a man who thinks he’s going to lose.

All this demonstrates great good sense, and, one would think, broad man-of-the-people appeal. But it doesn’t make for sizzling copy for journalists like me. Plenty of middle-aged blokes like pop music and football and cooking. Plenty of us enjoy spending time with our families, worry about our kids’ futures and throw ourselves into our work. Nothing exceptional or fascinating about it. That is both not Starmer’s problem, and also maybe his problem. He’s not trying to draw attention to his family life. But he is trying to draw attention.

Perhaps, too, it arouses its own kind of suspicion. We’re not accustomed to senior politicians coming across as well-adjusted and down-to-earth. Based on recent elections, we seem to like our politicians to be weird. They look weird, they sound weird and so it shouldn’t come as a surprise when it turns out that they are weird. Why isn’t Keir Starmer weird? What’s wrong with him?

As with so many aspects of contemporary life, there’s a silly social-media term for it: main-character energy. Margaret Thatcher had it. Boris Johnson has it. So does Donald Trump, the original American Bully XL. And Nigel Farage, the bolshy Brexiteer. It’s not only right-wingers. Bill Clinton. Barack Obama. Tony Blair. Even, in his way, Jeremy Corbyn. Love them or loathe them, it’s hard to ignore them. A useful trait if you’re running for the highest office — although it doesn’t guarantee electoral success. (See: Corbyn. And also Farage, who has failed seven times to become an MP.)

It’s difficult for a politician to run for office as a safe pair of hands, a sober, disciplined managerial type who seeks power not for personal aggrandisement but because he believes he can make a positive difference. Starmer is not campaigning as a radical idealogue or a visionary or a cult leader. He does not have a single issue to campaign on. He is not trying to galvanise a core demographic in opposition to another, as populist leaders do. He wants to unite rather than divide. “Working people” is the constituency he targets; that’s a lot of people.

His style is not entertaining. It’s not — another stupid internet term — a mood. He’s deliberate, meticulous. Friends may talk about how funny he can be in private. But he doesn’t do knockabout comedy in public. He sticks to the script.

“I look at other countries,” says Parvais Jabbar, “and they don’t say, ‘Our leader is funny.’ They say, ‘Our leader is a serious person.’ I look at my own job. If someone said to me, ‘Can you do it in a charming, funny, entertaining way?’ I can just say, ‘Well, no! It’s a serious job!’ It’s different in politics. But I do think most people want to know that the man or woman at the top is a serious individual. Not just an entertaining person. Keir’s going to do it his way. And if I was advising him, I’d say that is something he must stick to. There will be moments to entertain and be engaging. But don’t be flippant.

“We’ve had clownish,” concludes Jabbar. “Where has that got us?”

Twenty-plus years ago, as we drove up the M40 from London to his Oxfordshire constituency in his Toyota people carrier, I asked Boris Johnson why anyone reading the profile I was then writing of him, for a men’s magazine, should vote Tory. Among other reasons, he promised that under the Conservatives, as the result of higher standards of living, the average British bra size would increase — “superior mammary development” he called it — and why wouldn’t any red-blooded male vote for that? Different times, for sure. But a measure, in miles not inches, of the distance between the then MP for Henley-on-Thames and the current MP for Holborn and St Pancras: in style, in attitude, in everything.

(God and Google forgive me for checking, but it turns out Johnson’s prediction was correct: the average British bra size has indeed risen under the Tories, but as a result of increased obesity, which is linked to poverty rather than wealth.)

On that occasion, in 2002, I encouraged Boris to caper and fool, and I confess I was somewhat charmed and undoubtedly amused by him. (I also went on to write for him once or twice at The Spectator, when he was editor.) At the time, he told me there was more chance of my being “blinded by a champagne cork or decapitated by a Frisbee” than of his being elected Prime Minister. I thought he was almost certainly right about that. The idea was preposterous. As I say, different times.

It’s sometimes said that we get the leaders we deserve, in which case we must have behaved extremely badly in recent years. Have we pulled our socks up? Do we deserve the professorial Sir Keir, with his talk of “dignity” and “respect”, his appeal to our better judgement, his promise that he will do his utmost to improve all our lives and put the country back on a solid footing after years of chaos?

And whether or not we deserve him, is he what we want? Has our society, our political culture, become too trivial, too in thrall to drama and celebrity? Will Britain vote for a private man, in presentation highly conventional, in public cautious and restrained, eager to be judged on deeds not words? Have we grown too accustomed to being romanced by professional seducers? Is his sincerity not to his detriment?

“I honestly don’t meet many people who say to me, ‘The answer to my problems is an entertainer,’” he says to me, in Dagenham. “I really don’t. This just doesn’t happen.”

I return to the charisma question on the phone. Would Starmer say that the public perception of him is accurate? He says he thinks an accurate characterisation would be of “someone who recognises the challenges that are facing working people, recognises them and wants to roll up his sleeves and get on and fix them. Some people don’t recognise the challenges in the first place. They don’t understand what people are going through. I think that I do understand. I do actually know what it is like to not be able to pay your bills. That isn’t a prerequisite of leadership, but it does help. And then some people, even if they’ve identified the challenge, are so overawed by it that they can’t fix it. I’m a fixer of problems.

“There’s another element, as well,” he says, “which I do think is really important. That is an absolute determined focus on winning. People say about football that it’s the taking part that counts. I’m not in that camp. That’s not a phrase I’ll ever take to heart.

“Alex,” he says, “I play football every week.I watch Arsenal every game. And I want to win. It’s an absolute focus for me. Whether on the football pitch or in politics. That’s why the years since 2015 have been so frustrating, because we haven’t been winning. We lost in 2015. We lost in 2017. We lost in 2019. There’s nothing good about being in opposition. When I’m asked, what’s the worst job I’ve ever had, my answer is: Leader of the Opposition. You are not changing lives by being in opposition. You need to be in government.”