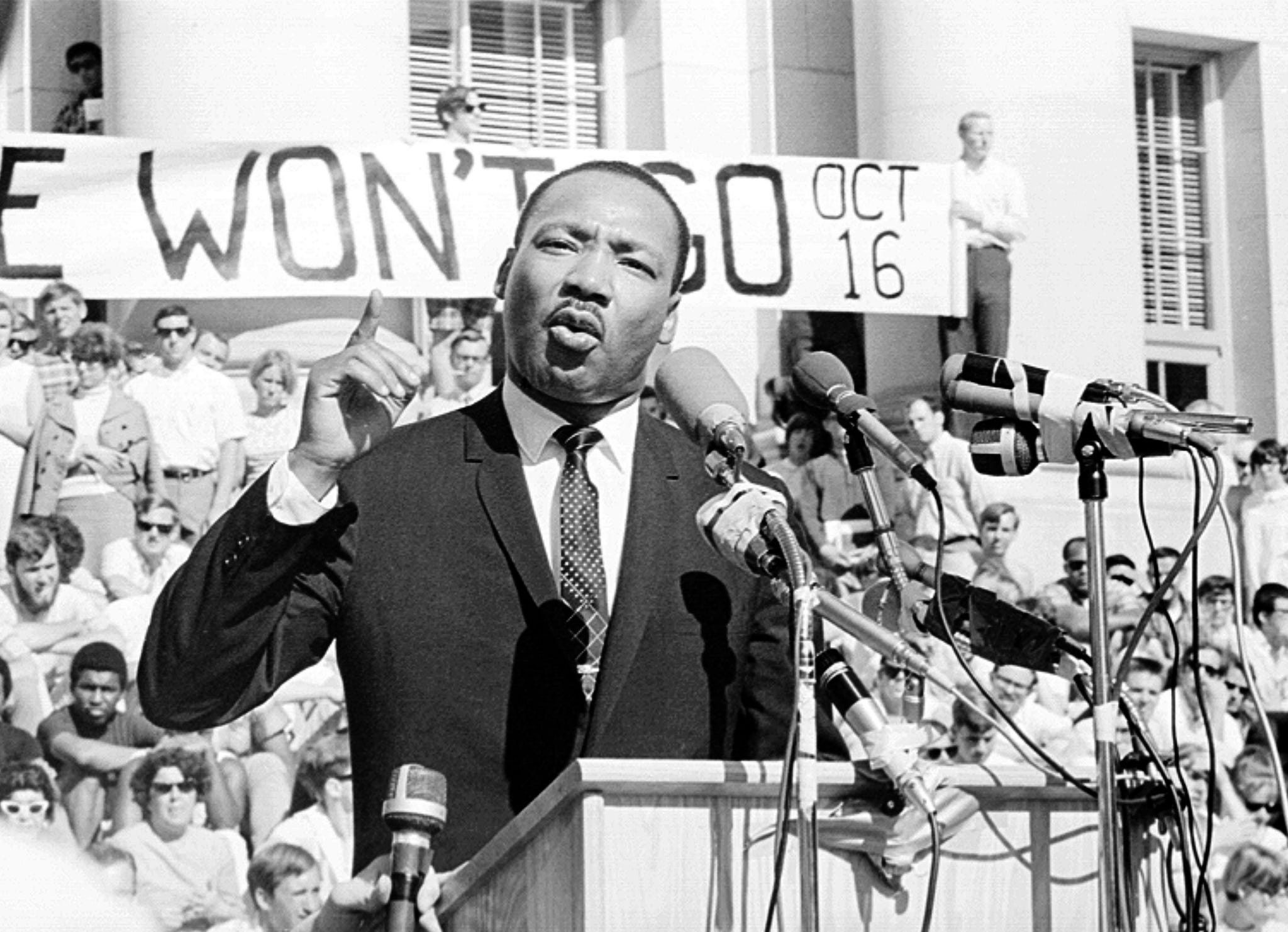

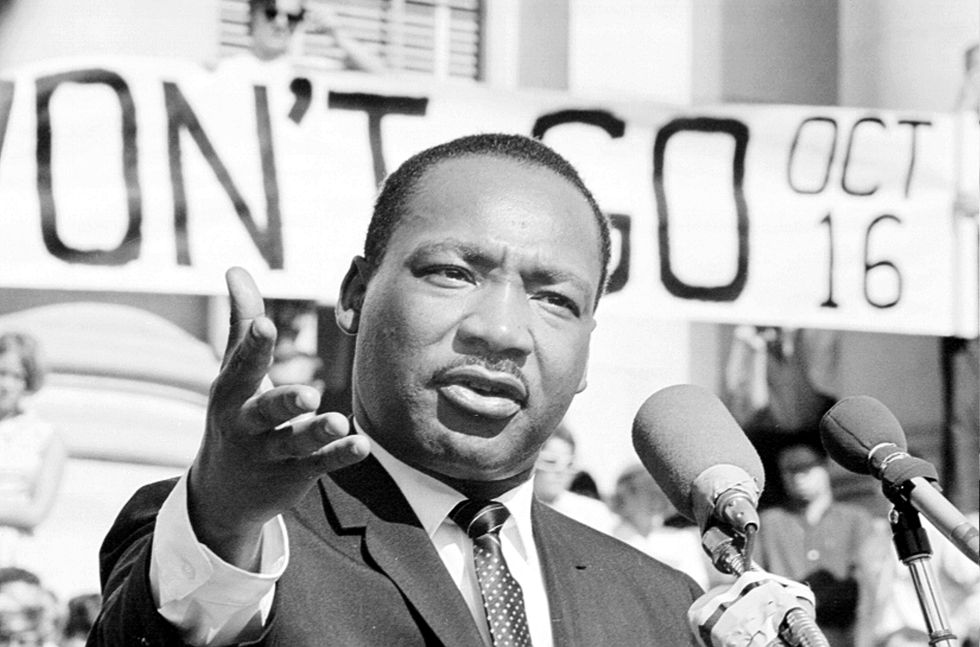

The whitewashing of Dr Martin Luther King Jr's legacy has a habit of negating his complex relationship with race relations in America. It establishes him as the epitome of what protesting is meant to look like for black communities. We’ve manipulated his legacy to fit a narrative that is more comforting for the masses. So much so, that when even King’s own children try to clarify his words, they are told they are wrong and that they don’t know their father.

This is an insidious way to apply respectability politics to diminish and discredit the frustration and anger felt in the wake of violence against black bodies. While it is undeniable that King’s preferred method of protest was to lead with peace and love, when we reduce him only to this ideology it erases a significant part of his activism, which included acknowledging the core causes behind other more militant approaches towards the fight to justice.

In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr was arrested in Birmingham, Alabama, for protesting. While in jail, King penned an open letter that the black community can still turn to; giving us the words to explain why, after so much time has passed, we are still not OK.

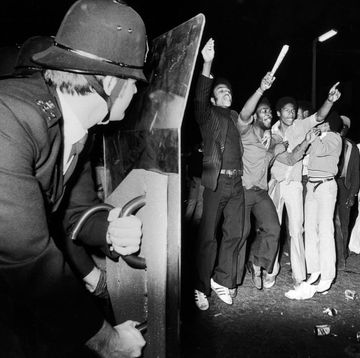

When you declare that the police are “just doing their job”, we say: "You warmly commended the [...] police force for keeping 'order' and 'preventing violence.' I don't believe you would so quickly commend the policemen if you would observe their ugly and inhuman treatment of Negroes [...] I'm sorry that I can't join you in your praise for the police department." (Letter From Birmingham Jail, 1963).

Dr. King regularly criticised both the police department and the US government for repeatedly failing to protect black communities. Historically speaking, police officers have also been active members of the Ku Klux Klan, and the issue continues to this day. In 2006, the FBI actively warned police departments of the infiltration of white supremacists within their ranks. On 29 May, Donald Trump tweeted: “When the looting starts, the shooting starts” – the same bigoted words Florida police chief Walter E Headley used in 1967, effectively encouraging violence against largely peaceful protesters. When we talk about 'systematic racism', these are just a few of the ways in which it manifests itself in American society.

When you passionately declare, “Not all cops!”, you must remember: "History is the long and tragic story of the fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but [...] groups are more immoral than individuals." (Letter From Birmingham Jail, 1963).

I can concede, maybe not all cops are bad. Perhaps King may have agreed too. However, don’t forget that King believed that if you are not actively fighting against dismantling the system, you are working towards preserving it.

If a “good” cop chooses not stop a bad cop from acting immorally, the “good” cop doesn't deserve credit for not being an active participant in violence. They deserve criticism for not stopping their colleagues from doing the bad thing in the first place. The same holds true in every facet of our lives in which inequality and injustice exists and prevails.

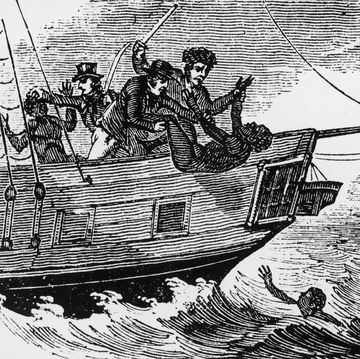

When you try to rationalise that the wrongdoer has been arrested and charged, and argue that we should have faith in the criminal justice system to find him guilty, we say: “When you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick, brutalize, and even kill your black brothers and sisters with impunity... then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait” (Letter From Birmingham Jail, 1963).

How many times have we been here before? How many times do we have to go through the pain and trauma of a trial that only ends in an acquittal? We cannot continue to wait around for justice within a system that was not established to give us such. So, while King may not have agreed with particular methodologies taken by some people today, he would not have told us to wait.

When you are so convinced of your own version of history that King would have condemned the actions we are taking today, I say to you: “For the salvation of our nation and the salvation of mankind, we must follow another way. This does not mean that we abandon our militant efforts. With every ounce of our energy we must continue to rid our nation of the incubus of racial injustice." (Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos Or Community, 1967)

To honour King is to honour his entire life. And towards its end, King began to have a shift in perspective. Notice how he uses the first-person plural “our”, including himself in these militant efforts. He understood that there was value and necessity in each way individual groups within the community sought freedom. While his approach was primarily of love and peace, he knew that other parts of American society were unresponsive to his methods. His ultimate goal was to end the inequalities that exist and uplift a community that has been and continues to be exploited and oppressed.

Here’s the thing. We are not so naive to believe that we can entirely eradicate an individual’s deeply rooted commitment to racism overnight. But, like King said in 1962 address at Cornell College: “It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important [...] We need legislation to control the external effects of those bad internal attitudes.”

There are inefficiencies within our current criminal justice system and not only within the police fraternity. Extrajudicial misconduct will not be addressed until it is demanded by the people: through protests or evidence in the form of phone footage. The law continues to fail in protecting some of our most vulnerable populations. King was demanding systematic change. If you read 'Letters From Birmingham Jail' and 'Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community', you’ll find that King repeatedly addresses the idea that tension and pressure creates action. Through protests and riots, we are actively applying tension to the system to create the necessary changes we have been fighting for since the Civil Rights Movement of the Fifties and Sixties.

And guess what? It’s working. After just a few days of protesting, governments are listening. At the time of writing, Philadelphia's elected officials released a list of reform measures that they are pushing to be implemented at both the local and state level. Some of these reforms include officers becoming mandated reporters of misconduct or corruption, as well as a civilian led review board.

It is time we stopped using the watered down version of Dr King as a way to postpone justice that he gave his entire life to create. If we truly want to honour his life and his work, then it’s time that actionable measures be taken.

J O Acholonu is professionally trained African-American educator committed to decolonising the literary canon and curriculum. Follow her on Instagram (@oh.jo.go) and Twitter (@oh_jo_go).

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts