"Have we got a serious player here?” asks Andrew Castle, the 59-year-old former No. 1 British tennis player and now the BBC’s voice of Wimbledon, looking me up and down. His gaze goes down my Richie Tenenbaum polo shirt and lands on my Veja trainers, which have solid eco credentials and non-marking soles but unmistakable weekend-dad energy, and he winces. “Hmm, I guess not.”

We are at the National Tennis Centre in Roehampton, west London. But we are not here to play tennis. Instead, we are limbering up beside a padel court, which is 20 metres long and 10 metres wide, or roughly three-quarters the size of a tennis court. It is enclosed at the back with glass and on the sides with glass and mesh. Padel, which was devised in 1969 in Mexico, borrows some core traits from tennis: you bash a furry ball over a net, and use the same scoring system; and some from squash: the back wall is in play, so long as the ball only bounces on the ground once.

Padel, which is said to be the fastest-growing sport in Europe, is almost always played in doubles and I’ve teamed up with my coach (who introduced me to the sport all of 45 minutes ago), James Rose, a tennis lifer who now works for Game4Padel, an ambitious operation backed by Castle, Andy Murray and Liverpool FC’s Virgil van Dijk. Castle is paired with Benedict Newman, who is in his early twenties and, ominously, is wearing a tracksuit with a Great Britain flag on his right pec.

Castle covers the base of his Wilson racquet and asks whether the logo reads, “M” or “W”. “M?” I guess. Castle shakes his head, “W, fuck off!” He elects to receive serve and, to everyone’s surprise, Rose and I hustle into a 3-0 lead. At the change of ends, Castle brushes my shoulder and mutters, “I’ve had some tough losses in my career,” perhaps reflecting on the time he went down to Mats Wilander, the No. 2 seed, in five sets at Wimbledon in 1986, or defeat in the 1987 Australian Open mixed-doubles final. Or perhaps not. “But this,” Castle confirms, “would be the most embarrassing.”

Still, you don’t reach the last 32 at the 1987 US Open by just rolling over and having your tummy tickled. Castle comes out swinging, or maybe he’s just actually trying for the first time, and starts playing lights-out padel. He and Newman take four games in a streak to go up 4-3, then 5-4 in our one-set match. When I blaze an ungainly forehand out of the court complex, Castle snorts, “Nice cricket shot!”

Truth be told, I was surprised as anyone to be receiving good-natured smack talk from Castle. Padel had been sold to me as a social game: less energetic and nerve-shredding than tennis. This is a sport where you might find a court-side DJ, and the losing team buys the first round at the bar. But as Rose and I — OK, mainly Rose — scrabble to save four match points, it doesn’t feel like that. My glasses are steamed up, my hand is sticking to the leather handle of the fibreglass racquet and sweat pools in my socks. The game goes into a decisive tie-break and another match point comes and goes for Castle and Newman, before Rose and I have one of our own. We make it — I’m not sure how, and frankly I can’t see much out of my glasses — to claim the set and match 7-6. It’s not the best day of my life, but is certainly right up in the top five.

The next day I catch up with Castle for a debrief. “Funnily enough, I didn’t lose that much sleep over it,” he says with a bark of laughter, when I ask about the five fluffed match points. “So you can take your self-satisfaction and stick it up your arse.”

Our match has given me a glimpse into why padel is on the rise. The familiar stress points of tennis — duffing your serve into the net, constantly crashing the ball wide or long — are largely removed from padel. The game suits children and older folk, because there’s less court to cover, and allows players of widely diverging abilities to share the same space. It would be ludicrous for me to step on a tennis court with Castle, but padel is a leveller. “Because you tried your backside off, you were involved,” says Castle. “In tennis, would we have had such a fun game? I doubt it.”

For Rose, who first saw padel when he was director of tennis coaching at La Manga Club in Spain, the sport is the perfect combination of being easy to pick up but hard to master. “You just see people leaving the court smiling and saying, ‘When can I play again?’” says the 44-year-old. “And being a coach all my life, to have that instant reward and reaction is very fulfilling. Because I love sport, ultimately. I’m a sport guy: tennis is my main sport, and I’m now heavily focused and involved in padel. But ultimately I just love people to get a buzz from sport.”

Padel has exploded in Spain, where around five million people play, and also in Argentina, Sweden and the Netherlands. Footballers especially seem to have taken to it: Leo Messi and Zinedine Zidane have courts in their gardens; Zlatan Ibrahimović is an investor in Padel Zenter, which has five centres in Sweden and one planned for Milan this year. There are courts in the training centres at Manchester City and Liverpool; the latter club recently posted footage of a tense, deftly skilled match between manager Jürgen Klopp and star striker Mo Salah. “Besides football,” an “addicted” Klopp has said, “it’s the best game I’ve ever played.”

All of which makes the rush to invest in padel not too surprising. There are currently just over 200 courts in the UK; that number is expected to double this year, according to the Lawn Tennis Association. Some of these new facilities will be in leisure centres, such as the Better Gyms chain, which has plans for more than 20 venues. But others will be in less expected places. In November last year, Game4Padel dropped a pop-up court in the central atrium of the Westfield shopping centre in west London; over three days, around 250,000 people watched exhibition matches between the Murrays, Andy and Jamie, top British padel players and the likes of TV presenter Jamie Theakston, model Laura Bailey and cricketer Andrew Strauss. Westfield has a 10-year deal with Game4Padel, and this year they plan to install three permanent courts.

The business case for padel starts to look compelling. Sport England calculated that the number of tennis players in England dropped from 889,300 in 2016 to 641,800 in 2021, or a 28 per cent dip in five years. (Squash had 425,600 players in England in 2016, but only 105,600 in 2021, which, even allowing for the Covid pandemic, is a jaw-dropping haemorrhage of engagement.) “It’s just a really fun game,” Andy Murray, who invested in Game4Padel in 2019, tells Esquire. “I played recently with my brother Jamie at Westfield and we just had a laugh. It’s still pretty competitive but, because it can be quite fast-paced, and you are all close together on the court, it makes it more sociable.”

At the National Tennis Centre, I ask Andrew Castle if tennis — and squash — should be concerned about the growth of padel. “Tennis has got a hundred-year head start, and that’s pretty powerful,” he replies. “But worrying about padel is a bit like worrying about water flowing downhill. Anybody who’s worried about whether or not padel is happening is a little behind the times. Because, by the way, it’s happening.”

In the US, the same conversations are taking place about an existential threat to tennis. But the tennis-adjacent disruptor sport over there isn’t padel, it’s pickleball. Around five million Americans are estimated to play the game, and these include George and Amal Clooney, who have a court at their home in Los Angeles. Kim and Khloe Kardashian played a match in a 2019 episode of Keeping Up with the Kardashians, and Larry David admitted enjoying a game on Curb Your Enthusiasm (his wife, Ashley Underwood, is making a documentary about the sport). At a charity tournament last November, Emma Watson teamed up with Sugar Ray Leonard — “I had, honestly, the best day of my life,” Watson said afterwards — while in the same month, Oscar-winning actor Jamie Foxx launched a range of racquets, the Best Paddle. His first customers? Will Smith and Leonardo DiCaprio.

Pickleball and padel share some similarities, not least in their origin stories. Pickleball was born in 1965 on Bainbridge Island, near Seattle, the invention of three dads: future US congressman Joel Pritchard and businessmen Barney McCallum and Bill Bell, who came home after a game of golf and found their families climbing the walls. Pritchard’s garden had a badminton court, but no kit, so the men and their kids started hitting a perforated plastic ball over the net with ping-pong bats. The following weekend, they lowered the net to roughly the height of a tennis net and over time they introduced custom paddles.

The name of the new game, coined by Pritchard’s wife, is usually understood as a reference to “pickle boats”: a sailing term for the last boat to finish a race, and a nod to the tossed-together basics of the new sport. Or it might be that the Pritchards had a dog called “Pickle” who liked to chase the ball — no one exactly remembers. Pickleball became popular among a small Pacific Northwest elite; one of the early acolytes, in fact, was a young Bill Gates.

Padel’s origins were equally rarefied. The game was devised by a Mexican industrialist, Enrique Corcuera, who didn’t have quite enough space in the grounds of his holiday home in Acapulco for a tennis court, so squashed one in a space that had walls at both ends. In 1974, Alfonso de Hohenlohe-Langenburg, a Spanish prince, visited Corcuera and liked the game so much that he took it home to his private club in Marbella. The Spanish tennis great Manuel Santana was an early ambassador of padel, but like pickleball, it remained a niche hobby for decades after its invention.

That changed in the Covid pandemic, as both sports saw their ranks swell dramatically in many places during the widespread lockdowns. Part of this growth was practical: padel and pickleball tend to be played outdoors, and involve no physical contact, so didn’t receive the strictures that other sports such as football, basketball and swimming had. Manu Martin, a Spanish padel player and coach with a strong social-media presence, found himself becoming an influencer in the Covid era: he now has 185,000 followers on Instagram. “It sounds bad, but the pandemic was good for padel in Spain, in Europe and in many countries,” says Martin. “One reason is that, once you have tried padel for one time, then you’re in love with the sport.

“And the second thing is about the business,” he goes on. “In one tennis court, you can install three padel courts. In tennis, people play one versus one, so if you’re a manager of a club, you’ll be earning money from two people. But if you have three padel courts, you have 12 people playing, paying and drinking beer in the cafeteria after the match. This is very common, at least in Spain and the Mediterranean: after padel, you drink beer. So as a business, it’s more interesting than tennis. And when people put money into a new sport, that’s when it begins to grow up.”

Pickleball has a crucial advantage over padel, though, in its capacity to expand as a sport: padel courts need to be purpose-built, and with the playing surface, glass and lighting, can cost up to £25,000; pickleball courts, meanwhile, can simply fit on an existing tennis court with new, taped lines. The racquets are typically cheaper for pickleball — though not if you want one of Jamie Foxx’s — and are usually more durable than padel bats. (At the top end, consider a sleek black Prada padel racquet, which costs £1,500, and the accompanying ball case, £320.)

But the fact that pickleball can so easily take over tennis courts has also led to considerable beef with the paterfamilias of racquet sports in the US. In response to a social-media post about “The Great Tennis v Pickleball War of 2022”, the tennis legend Martina Navratilova wrote on Twitter: “I say if pickleball is that popular let them build their own courts.” Navratilova added a little smiley symbol in the hope of avoiding the wrath of five million evangelical picklers, but the tenor of the debate has been turning nasty. In 2021, five litres of oil were poured on pickle-ball courts in Santa Rosa, California, along with a note threatening to scratch the cars of the pickleball players. In Brooklyn, a pair of pro-tennis, anti-pickleball enthusiasts started a group and Substack called Club Leftist Tennis with an introductory manifesto titled “Against Pickleball”. In September, they wrote: “Reminder: pickleball is an astroturfed, venture capital-backed parasite on public space.”

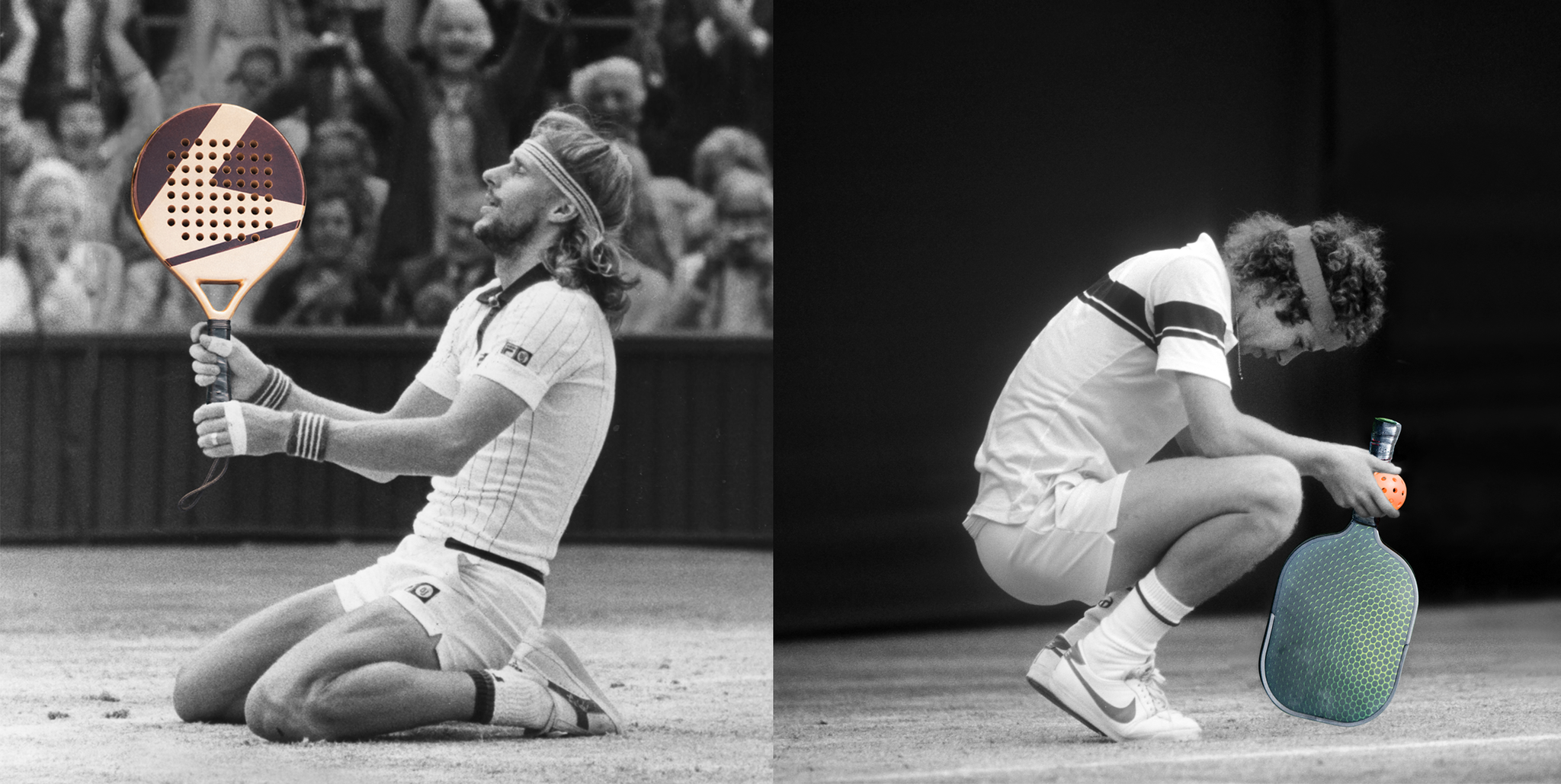

It’s not hard to find voices in the US sniping against pickleball. For some, it’s like kale: a fad with “a good publicist”; elsewhere, it has been compared to NFTs and cryptocurrency. The really sour critiques say it is like tennis, just for people who don’t have much co-ordination. But, right now, these complaints — some of which could also be levelled at padel — are being drowned out by the acolytes. There is special dismay that the Tennis Channel in the US has started showing professional pickleball matches, including — sacrilegiously — on the day that Roger Federer announced his retirement from tennis.

This year also sees the first edition of Major League Pickleball, a competition between 12 teams and 48 athletes, with a prize money of $5m. The list of team owners and investors is wild: among them LeBron James, Heidi Klum and Michael Phelps, as well as tennis stars Nick Kyrgios and Naomi Osaka. The DC Pickleball Team is bankrolled by an especially eclectic group that includes Desperate Housewives’ Eva Longoria, footballer Mesut Özil and model Kate Upton; their first pick in the draft was Sam Querrey, a Wimbledon semi-finalist in 2017. Last year, Noah Rubin, a 26-year-old American player who won Junior Wimbledon in 2014, also defected to pickleball. On hearing the news, the matriarch of British tennis Judy Murray wrote on Twitter, “Watch out tennis. Pickleball is coming for you…”

Steve Kuhn, a billionaire former hedge-fund manager who founded Major League Pickleball, has also announced the “40 by 30 Project”: an initiative to have 40 million people playing the sport by 2030. “It may sound like hyperbole,” Kuhn noted at the launch in October 2022, “but I really believe pickleball can save this country, and maybe even the world.”

Pickleball is not quite ready to “save” the UK yet, with estimates of around 5,000 regular players. To this end, when I contact Pickleball England to ask if they can fix me up with a game, I’m quickly paired with 27-year-old Louis Laville, who happens to be the No. 1 player in all of Europe. We meet at the Roehampton Club, a private members’ sports club in London that is, as it happens, just round a leafy corner from the National Tennis Centre, where Laville works as the golf and games manager until pickleball can start paying the bills. “I see it as a hobby,” he says. “Because until you can make it as a career, it’s essentially a hobby.”

Laville was turned on to pickleball five years ago by his mother, after she saw people playing it on holiday in Florida. He tried it, liked it, and found a group of like-minded souls in Epsom, Surrey and then west London to practise with. Today, he has arranged a doubles match with two of his colleagues at the Roehampton Club: Dan Lott, the racquets director, and Ollie Sunda, who works in events. The court is half an indoor tennis court that Laville spends 10 minutes marking out with electrical tape.

Pickleball, you quickly learn, is all about the “dink”. The evil twin of tennis’s drop shot, the dink is lethal in pickleball because on either side of the net there is a “no-volley zone” (aka “the kitchen”), which extends a little more than two metres each side of the net. A perfect dink will dip into the no-volley zone, bounce low, leaving your opponent with little option but to float up a looping return, giving you an easy put-away. Of course, mis-hit your dink and you will dump the ball into the net or dish up a straightforward smash. (In padel, the dink would not be a good tactic, because players can lurch as close to the net as they want; instead, a perfectly executed lob that lands where the court meets the glass is pretty well unreturnable.)

For me, pickleball felt closer to playing a traditional game of tennis than padel did. Weight of shot is important, because you don’t have padel’s back wall to help you out, and a player with tight volleying skills — such as Laville — is lethal in pickleball. With Laville pouncing on any loose shots, we take the first set against Lott and Sunda. The rules take a bit of getting used to: only the serving team can score a point and the game is played to 11; the victorious pair must win by a clear two points. But in the second set, my dink game goes awry and I offer up too many easy smashes to Lott and Sunda. The match ends one set apiece.

Afterwards, we have a debrief on where pickle-ball and padel are heading. The Roehampton Club, where we played, has always been a tennis hotspot: it has 30 courts, both indoor and outdoor, all different surfaces; players tuning up for Wimbledon have been known to practise here. But the club has already started diversifying its offering: it recently added two padel courts, and Laville gives pickleball taster sessions for members. “It’s good that you’ve got two sports that are supplementing tennis because in recent years tennis has started struggling a little bit,” says Laville. “I don’t want to say it’s a declining sport, but the reason padel and pickle are growing so popular is because people are con-

verting from it.”

And pickleball is gaining traction in the UK: it is now offered at 45 David Lloyd Clubs, mostly on repurposed badminton courts. For Laville and Lott, the racquets director, it simply comes down to demand. “In the next few years, a club that has four tennis courts might reassign one of those courts and have one pickle, one padel, as another offering for the members,” suggests Lott. The threat to tennis and squash is obvious, but are padel and pickleball also competing against each other? Are they locked in a winner-takes-all duel? Laville doesn’t think so. “You’ll see both really grow in the next few years,” he says. “I’m biased, but I think pickleball may, long-term, do better, just because it’s much easier to get started, and you don’t need a purpose-built court.”

What might be decisive, in the next decade, is whether either of these upstart sports receives the Olympic nod. Padel, with its global reach, seems to have the advantage over the more US-centric pickleball. To fulfil the Olympic criteria, a sport has to have 75 national federations: padel hopes to have the numbers by the Brisbane games in 2032. “If padel could get in the Olympics, that’s a big moment,” says Andrew Castle. “Because that means there would be state funding in China, perhaps — and I was going to say Russia, but we won’t even mention them sonofabitches.”

Will we one day see padel’s Roger Federer? The Serena of pickleball? Professional padel matches have already been screened on Sky and BT Sport in the UK. Last year, the Premier Padel Tour received major investment from Qatar Sports Investments, the company chaired by the president and CEO of Paris Saint-Germain, Nasser Al-Khelaifi. His plan is to introduce eye-catching prize money and an annual schedule of 25 tournaments, with four grand slams. “The world has only seen the tip of the iceberg of what the sport of padel can achieve on the global stage,” said Al-Khelaifi, who briefly had a tennis career, reaching a top ranking of 1,040 in 1993.

For now, tennis is keeping an eye on its precocious younger siblings. At the moment, it’s still strong enough to bully them if the fight becomes physical, but padel and pickleball are growing up fast. And, as for squash, it may be too late. “Most of the tennis players I know play padel and enjoy it but they wouldn’t give up tennis for padel,” says Andy Murray. “I think the two sports can sit side by side. Padel is a great way for people to start racquet sports because it’s so easy to learn, but the beauty of tennis is the technicality of the game. There will always be a place for that.” ○