On a crisp afternoon on 31 January 2010, error-prone Arsenal goalie Manuel Almunia became the first player to score in a live 3D broadcast when he tipped a looping cross from Manchester United’s Nani into his own net. It would prove a fitting start.

Nine pubs across the British Isles had been secretly selected to host the groundbreaking game. Dusty old TV sets made way for state-of-the-art 47-inch screens, and senior Sky technicians stood amongst the bespectacled crowds, anxiously awaiting their reaction. Will the sound sync up? Will people start vomiting en masse? Will it even work?

It was a curling corner kick that garnered the first big response, catching the camera at just the right angle. “I remember texting one of the guys at another pub, telling him that everybody had ducked,” says Ian*, a former Sky employee who worked on the project. “And I got a text back saying, ‘Everyone did exactly the same thing here!’” They watched on in delight as the gawping crowd, all decked out in Blues Brother shades, bobbed and weaved around the action.

Manchester United eventually ran out 3-1 winners, and pubs, punters and newspapers alike were suitably impressed. The Daily Mail, reporting from one of the clandestine broadcasts, boldly declared that “watching football has changed profoundly”. More than 1,000 pubs ordered 3D-enabled HD TVs from Sky and LG and many football fans began to buy their own pricy sets in preparation for the big roll-out. Sky even considered the prospect of hosting games at cinemas.

For many, watching 3D TV (especially with other fans, preferably with a pint in hand) sounded like a remarkably immersive midway point between sitting in the stands and staying at home. For others, it felt like needless stunt. “3D has always been such a gimmicky buzzword that people were always going to be reticent, especially football fans who pride themselves on sniffing out bullshit from well inside their own half,” says Sam Diss, head of content at football magazine Mundial.

For the Sky team, though, it was a no-brainer. The idea emerged from a preview screening of James Cameron’s Avatar in 2008 – a rare instance of downtime during their work on the launch of High-Definition TV. “We redesigned and re-engineered everything, from camera to screen,” says Ian. “If we’re talking about football, that means the cameras in the stadium, all the way through to the outside broadcast route, all the way through the production chain, and all the way to the set-top box. That was a mammoth task.”

So when a research and development lab told them that they could recreate Avatar’s 3D effect through their new HD set top box with relative ease, they jumped at the chance. “Effectively, you could create two pictures, one for the left eye and one for the right eye,” Ian says. “At the front end you’d just take two HD cameras rather than one. We were launching High Definition TV, video on demand services and catch-up. The box wasn't designed for 3D at all, but we didn't have to change anything. It just became another bit of icing on the cake.” They managed to develop the process in just six weeks.

When Jill and Dean Baker took over The Jolly Brewer pub in Stamford, Lincolnshire, in 2006, they had a lot of work on their hands. “It was a shithole that had no customers,” Jill tells me. “We built the business up, slowly but surely, and football was a really important part of that.” That’s why, after seeing the buzz around 3D TV, they decided to take a (not inexpensive) punt.

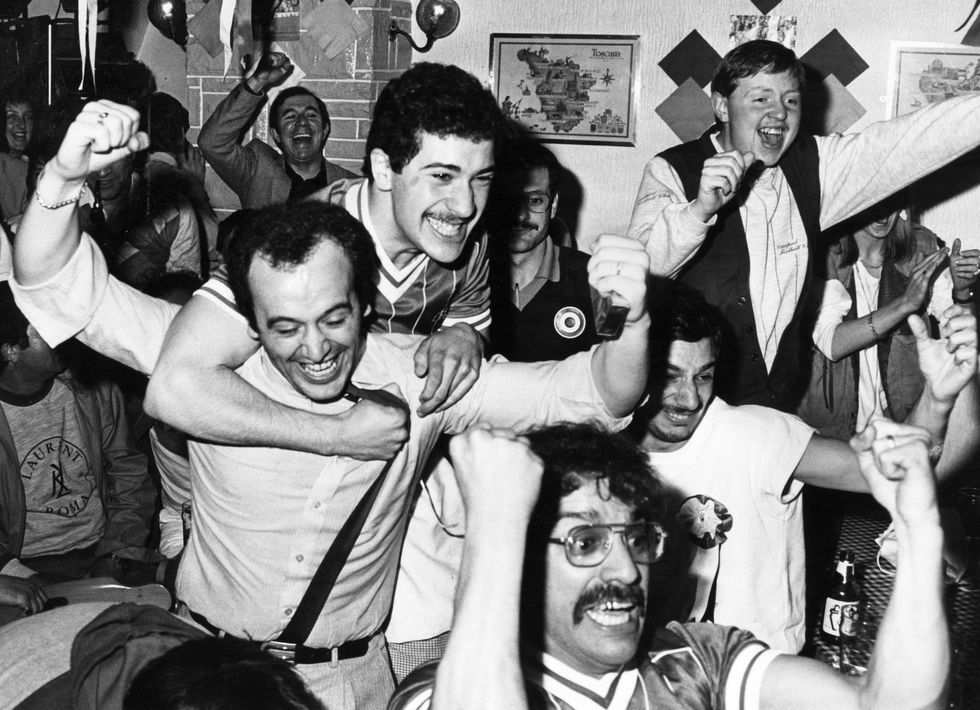

They bought two screens costing roughly £1,350 each and received 200 pairs of 3D glasses in preparation for the first game, a Premier League clash between Manchester United and Chelsea. Jill remembers the day vividly, because a busload of Newcastle fans unexpectedly arrived beforehand to watch their Championship fixture against Peterborough. “It was bedlam. On the whole they were well behaved,” she says. “Except for the few that grabbed my arse on the way out, which was not welcome.”

Soon enough, the Toon Army were replaced by hordes of excited locals. “Stamford is a small town and we were the only pub to do it initially. It was probably the busiest we had ever been,” Jill says. “We had one customer who was blind in one eye. No good for him, poor sod.” Demand was initially so high that Sky even built an online pub finder for fans seeking out 3D football across the country. They soon launched their at-home channels, and ESPN followed suit a month later.

At which point, the drawbacks of retro-fitting this kind of tech became apparent. “Camera positions had been agreed upon at stadiums, and they weren’t ideal for 3D,” Ian says. The technology worked best when the cameras were close to the pitch. The further up the stands you went, the less the impact, since a birds-eye view is basically 2D anyway. Watching games from the Emirates Stadium and White Hart Lane was great, Jill says, and the City of Manchester Stadium had its cameras hung so low that viewers could almost have been standing on the sideline. But the lofty angles at Old Trafford were the worst – making Man Utd’s constant presence on the TV schedule all the more frustrating.

Editing was a problem too. Live broadcasts frequently cut between different shots to give the viewer a sense of pace and geography, “whereas in 3D, effectively, you would do the opposite,” says Ian. "The shot itself has all the information that your eye needs." Ideally, you’d have separate production teams and techniques for each format. “But the mass audience is watching in 2D, so we had to compromise.” He thinks that golf, with its sloping courses and subtle perspectives, is the sport that came closest to realising the potential of the technology.

Then there were the health issues. Rumours circulated of headaches, eyestrain and nausea. Assurances from The Royal College of Ophthalmologists – "You cannot damage your eyes by watching in 3D" – did little to reassure sceptics. One instruction manual for a Samsung 3D TV set even warned that it was unsafe to watch the service while drunk – particularly worrying news for pub custodians. The story went viral, alongside other valuable pieces of advice pulled from the booklet (“DO NOT place your TV television near open stairwells” is a particular highlight).

Two months earlier, the mayor of Peterborough, Keith Sharp – who had just spent over £2,000 on his own 3D set-up – was stopped from renting Piranha 3D from his local Blockbuster on health and safety grounds. The fact that staff had misinterpreted the company rules (which banned them from renting out 3D glasses for hygiene reasons) didn't stop tabloids from whipping up fear and concern around the tech. Mark Pesce, an early pioneer of virtual reality, even warned that children "could potentially suffer permanent damage from regular and extensive exposure [to 3D images on a screen]".

But by far the biggest gripe, as many critics rightly predicted, were those glasses. Jill admits that customers were often shocked to walk into the Jolly Brewer to find crowds of boozed-up blokes huddled together in what looked like knockoff Ray-Bans. “We’d catch their eye and ‘reassure’ them we weren’t an insane cult, and that they were safe. It became a bit of a joke in the pub.”

Just a few short months after the TVs were installed, people started to grow bored of seeing the world through a pair of 3D frames. “I suppose, ultimately, our customers who come to watch football also come to drink beer, see their mates and chat,” she says. “If the football match is gripping, then great. But Premiership football isn’t always gripping. Many felt stupid wearing them, and the glasses impeded your ability to see your pint, order drinks and look in your wallet.”

For Diss, it was just a case of TV bosses not seeing the wood for the stereoscopic trees. “3D TV football almost tried to ‘fix’ the ‘problem’ of watching football at home or in the pub, without realising that there’s a real charm and positive to both,” he says. “Nothing beats the feeling of seeing football in the flesh, but watching it on TV is a real simple pleasure: letting you sit there in your boxers at home with a beer if you want it, or half-watching it in the pub with a roast alongside your mates if the mood strikes you. You don’t need to be ‘inside’ the game to enjoy it, and that’s what 3D never considered — having that critical distance is actually quite nice.”

For the sake of transparency, I should mention that my own memories are (unfairly) tarred by the fact that my local at the time, a shiny Brighton sports bar that resembled the Architect’s Room in The Matrix, had their lone 3D TV on a maddening 5-second delay. The first time I tried it, I found out about Theo Walcott’s brilliant solo goal against Chelsea at the precise moment he tripped over his own ankles and face-planted onto the ground in its build-up, as the groans of the 3D crowd I was watching with were drowned out by the roars of my fellow Arsenal fans behind us. Confusion reigned. I frantically switched back and forth between TVs, somehow managing to miss out on both the celebrations and goal (watch in glorious 2D from 1.33).

A decade on and I’m still bitter – Theo Walcott wonder goals were rare, ones that involved John Terry getting embarrassed even more so – but Ian certainly isn’t. He believes that the technology just wasn’t up to the task. “In my opinion it was too early, and people did not, at the end of the day, want to put glasses on in a pub. Maybe they [thought they] looked dumb. They certainly didn’t want to wear them at home.” That may have had something to do with the price of the things, too. Pubs would charge a small rental fee or hand them out for free – Jill charged punters a £2 deposit a pair. But consumers at home had to spend up to £80 for a single pair, depending on their specific television. If you wanted to watch the game with your family, or your mates, you could stump up more than you would for certain season tickets.

Over 1.5 million 3D TVs were sold in the UK over the course of the next four years, but the feature was often neglected, with only half of households choosing to watch the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympics in 3D. Meanwhile at pubs, fewer and fewer black frames were making it out of their boxes, with interest dwindling for months before finally disappearing. “Towards the end of the season we stopped charging a deposit,” Jill tells me. “At some point Sky sent us two more boxes for free, but we binned them.”

In 2013 Sky reaffirmed its commitment to 3D TV, but every football fan knows what follows the dreaded ‘vote of confidence’. One year later, the broadcaster announced that they would no longer show Premier League games in 3D. Months prior, ESPN and the BBC had quietly pulled the plug on their 3D services, citing a lack of public interest. Then Sky got rid of its other 3D channels, too. By the beginning of 2017, LG and Sony, the only two brands left selling screens, decided to cease production globally. 3D TV was officially dead.

But can it rise again? And more importantly, should it? “I don’t believe we’re going to be watching flat pieces of glass all our lives with a flat image," says Ian. "I mean, John Logie Baird [inventor of the first television in 1927] would probably be rolling in his grave thinking, 'God, is that all they've got to?'" (Baird actually exhibited a working 3D ‘stereoscopic’ model on 10 August 1928, but only one person could use it at a time while stood in a fixed spot, which rendered it commercially unviable.)

BT Sport has been experimenting with screening virtual reality matches through its app for three years, but experts believe that unwieldy VR headsets are even more of a stumbling block than 3D glasses. “There was always a barrier […] of putting something between yourselves and the viewer,” Steve Smith, Sky Sports’ executive director of content, told Westminster Media Forum last month. “That barrier of a headset, to a certain generation, is always going to be there."

But what if we can break down that barrier? According to analysis from investment experts Guru Focus, the glasses-free 3D TV market is set to experience significant growth over the next five years. Developers are currently racing to perfect the technology, with Dutch company Dimenco blowing everyone away with its 8K model at CES 2019, and Silicon Valley start-up Lightfield Labs doing pioneering work in the field of holographic display. Of course, it should be mentioned that glasses-free 3D isn’t exactly uncharted territory – Toshiba, Sony, Sharp, Vizio, and LG have all exhibited showpieces over the years, and Nintendo pulled it off (albeit to a lesser degree) with its 3DS games console in 2011 – but things are clearly ramping up.

Meanwhile, Premier League clubs have been exploring new 3D innovations. Last year, Arsenal, Manchester City and Liverpool followed the NFL’s lead by installing 5K ultra high definition cameras around their stadiums for Intel’s TrueView platform, which allows you to watch match highlights from any conceivable angle, transforming peoples’ living rooms into VAR bunkers.

The Covid-19 epidemic (and the potentially ruinous threat of legal action currently looming over clubs from unfulfilled TV deals) has forced sports bosses to rethink how they will eventually host and screen matches. In America, NFL broadcasters plan to pump crowd noise into stadiums and add digital fans into stands – a move that Sky Sports is reportedly exploring too. Once again, immersion is the name of the game.

For Diss, that would be the wrong approach. "The quality of broadcast is already super high, and I think that the fan experience for those watching at home could be improved immeasurably by some pretty simple things, like a strong, knowledgeable commentary team and pundits who aren’t troll-baiting," he says. "There’s a real purity to football — two goals, a ball; that’s it — and that extends to broadcasting too, for me."

One thing’s for sure: we’re on the verge of another technological arms race that could change football forever. The emergence of 5G, the superfast cellular network that has sparked conspiracies and arson attacks the world over, will open up new avenues for innovation. Last year, BT used the service to let fans project the FA Cup final onto their local park green, as well as place them into the Wembley crowd through VR (a hugely monetisable opportunity for clubs and TV companies).

According Matt Stagg, director of mobile strategy for EE, Covid-19 will only accelerate change. “At the moment, whatever happens and however this plays out, a football fan wants to be in the stadium and that’s it," he told the Sports Video Group in March. "If you’re not in the stadium, you want to be with your friends in front of a big screen. That’s not going to happen now. So what you end up with is you’re watching it on your own, so how do we enhance that experience?"

Critics will ask: if it ain’t broke, why fix it? And characterising sceptical fans as headset-mangling luddites would be missing the point. They’re merely defending the time-honoured tradition of watching football on TV, at the pub or otherwise, and all of its component parts: a foamy pint, your own sofa imprint, the ability to talk to friends without being shh!-ed by binocular-eyed tourists. It’s a cherished experience that stands alone, no lesser for it.

But there’s also no doubt that immersive matchday experiences will open the game up to the millions who have been priced out of Premier league stadiums, and those who are unable to attend matches for health reasons. What's more, you can’t stop progress. Eventually, through trial and error and endless Kevin Bacon adverts, something will stick.

“At one point, people were even debating whether video-on-demand was worth doing,” Ian tells me, reminiscing over his time in the television industry. “Now look at us. Yeah, I think 3D TV will have its second bite of the cherry.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts