Out of a swirling fog emerges the prow of a boat, knifing through a foaming sea. Two figures, shadows in the murk, stand silhouetted on the foredeck, confronting the horizon, their backs to us. Presently an island swims into view. No more than a crag, really: lonely, battered, forbidding. Then a lighthouse can be made out, blinking in the gloom.

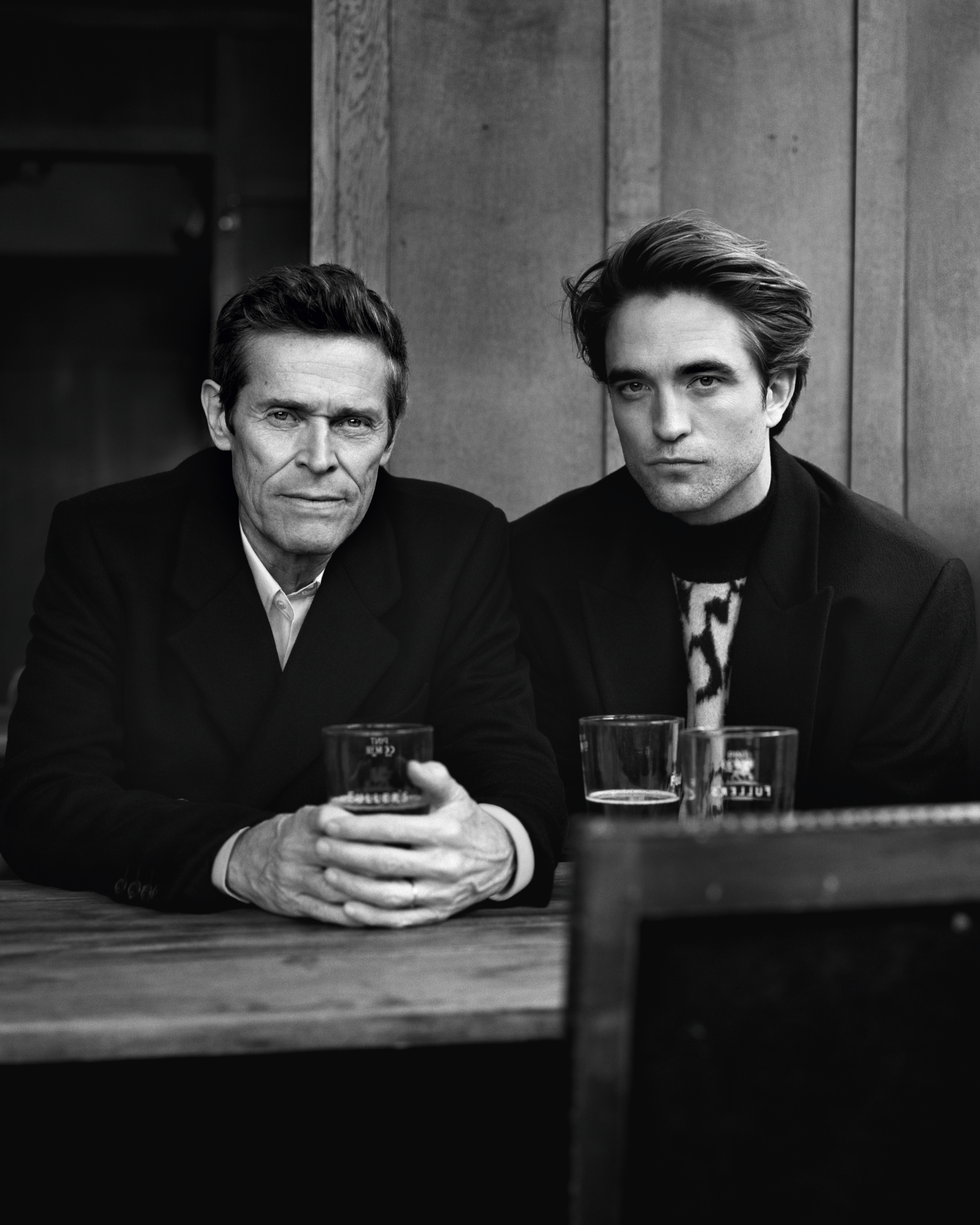

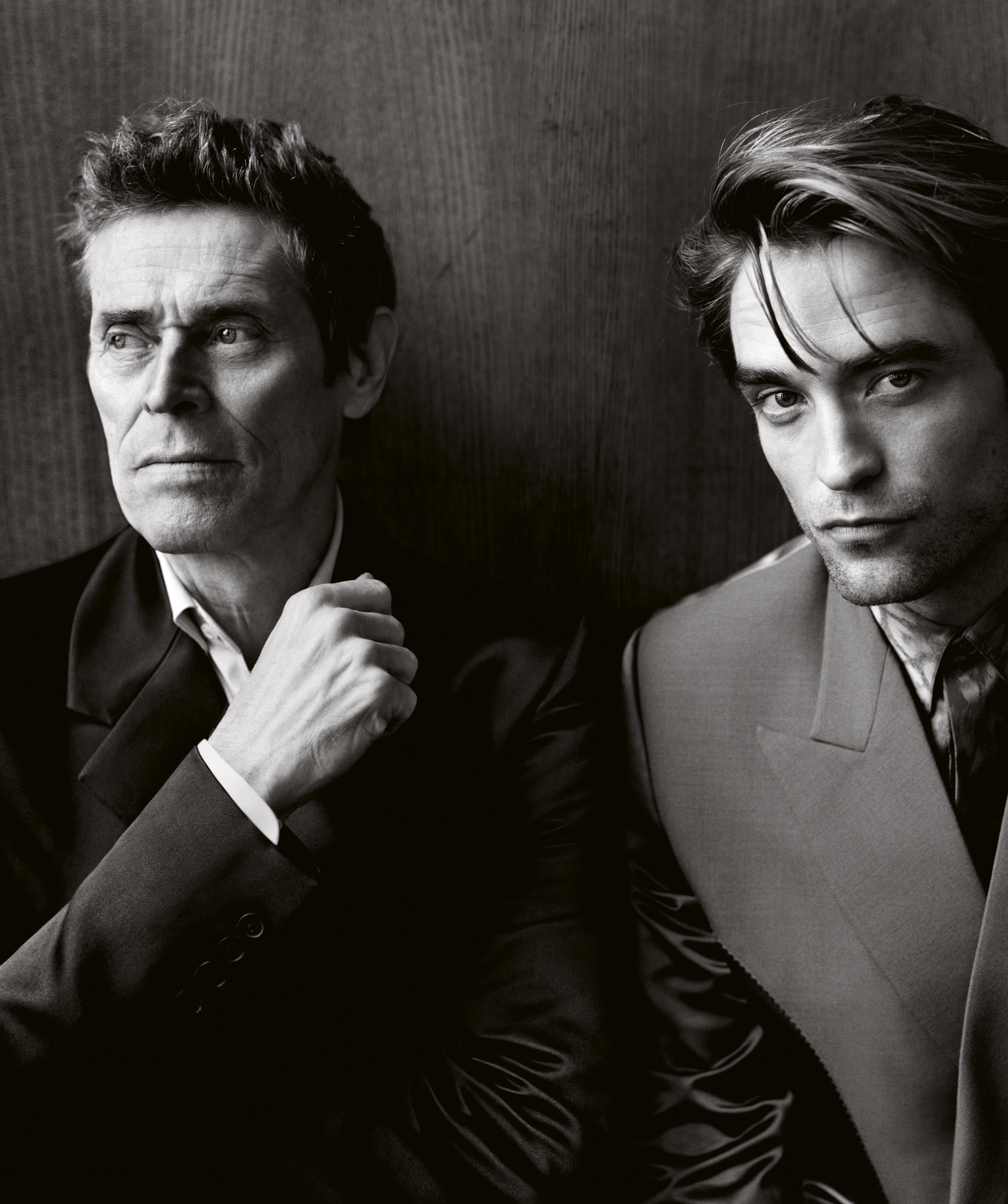

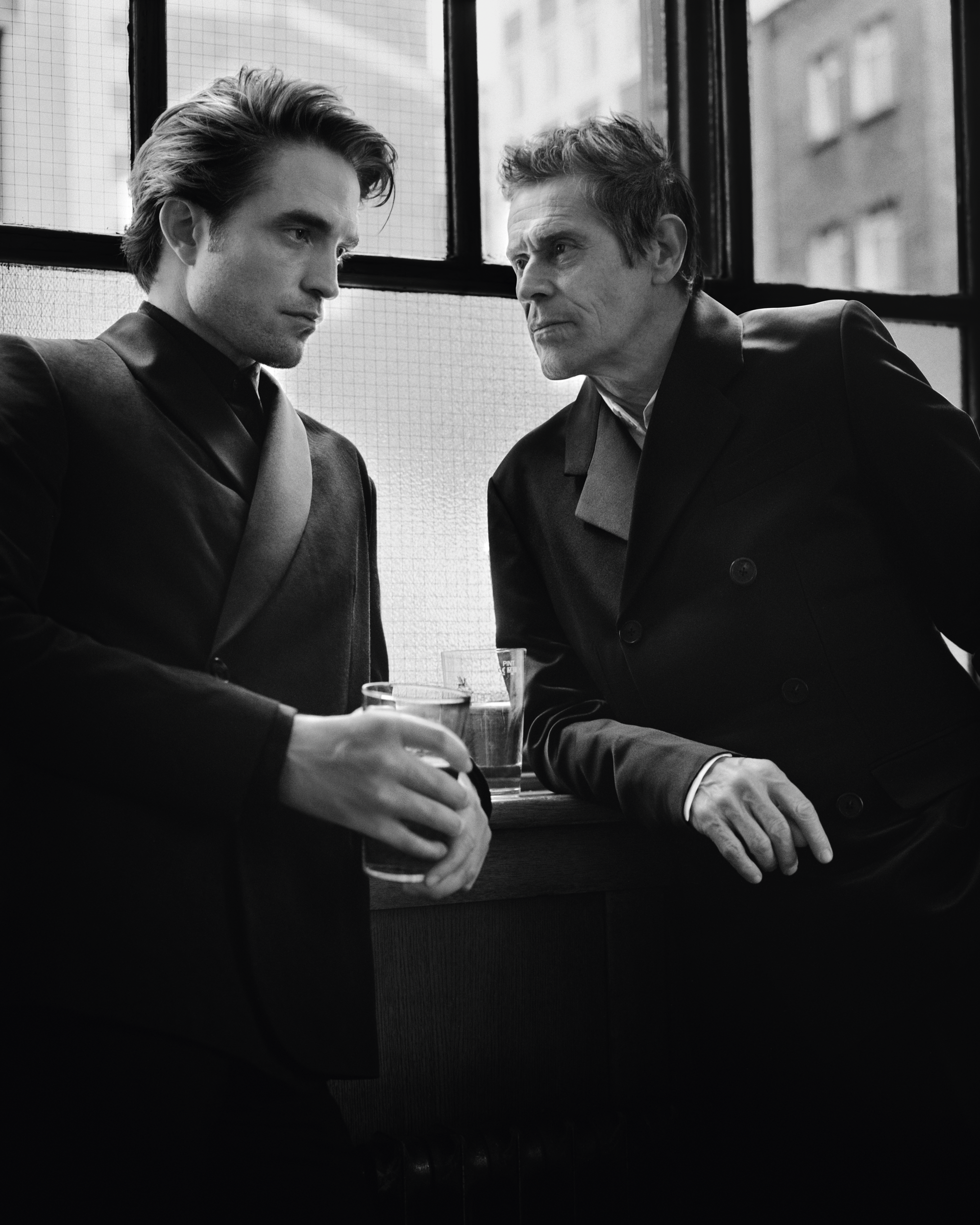

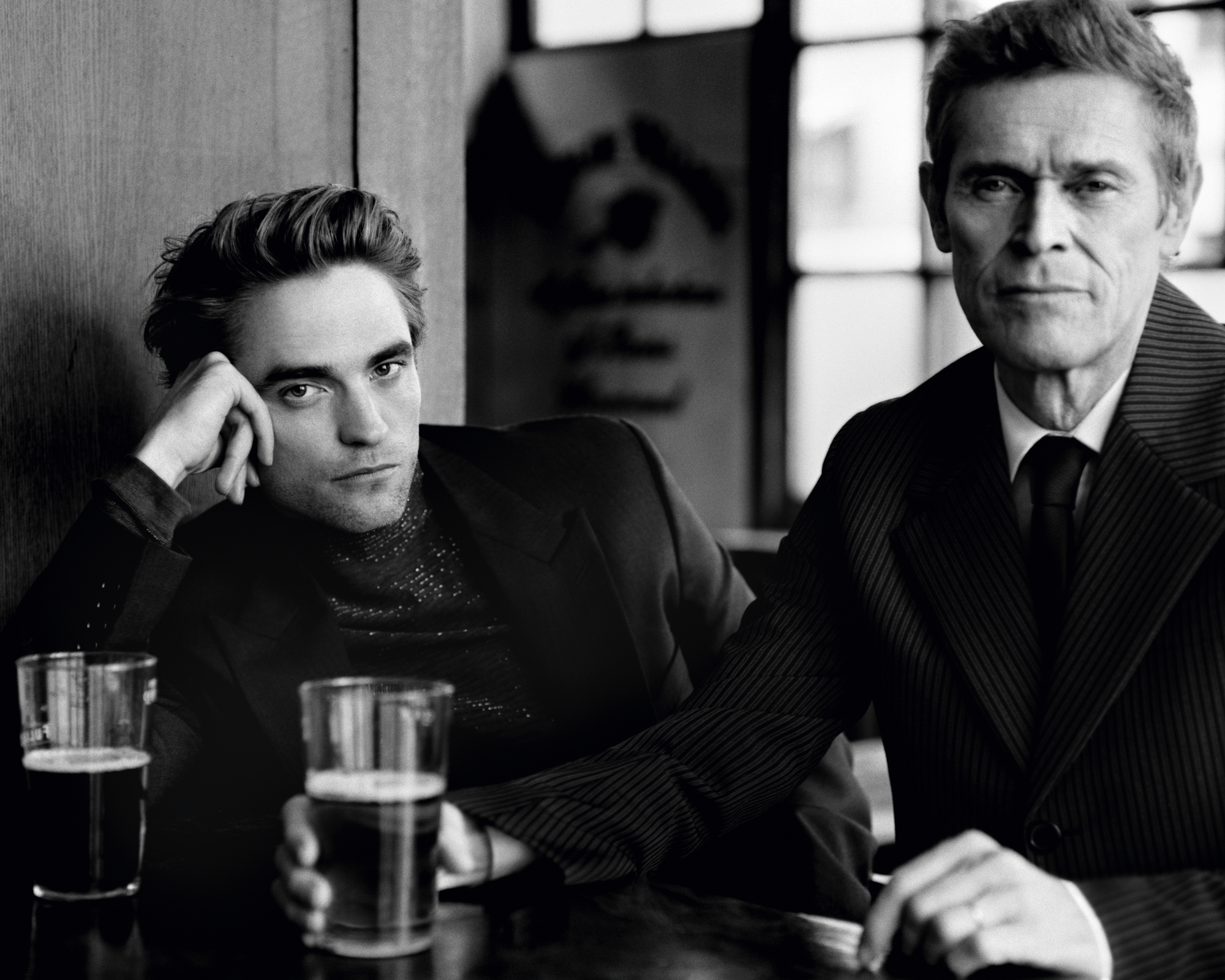

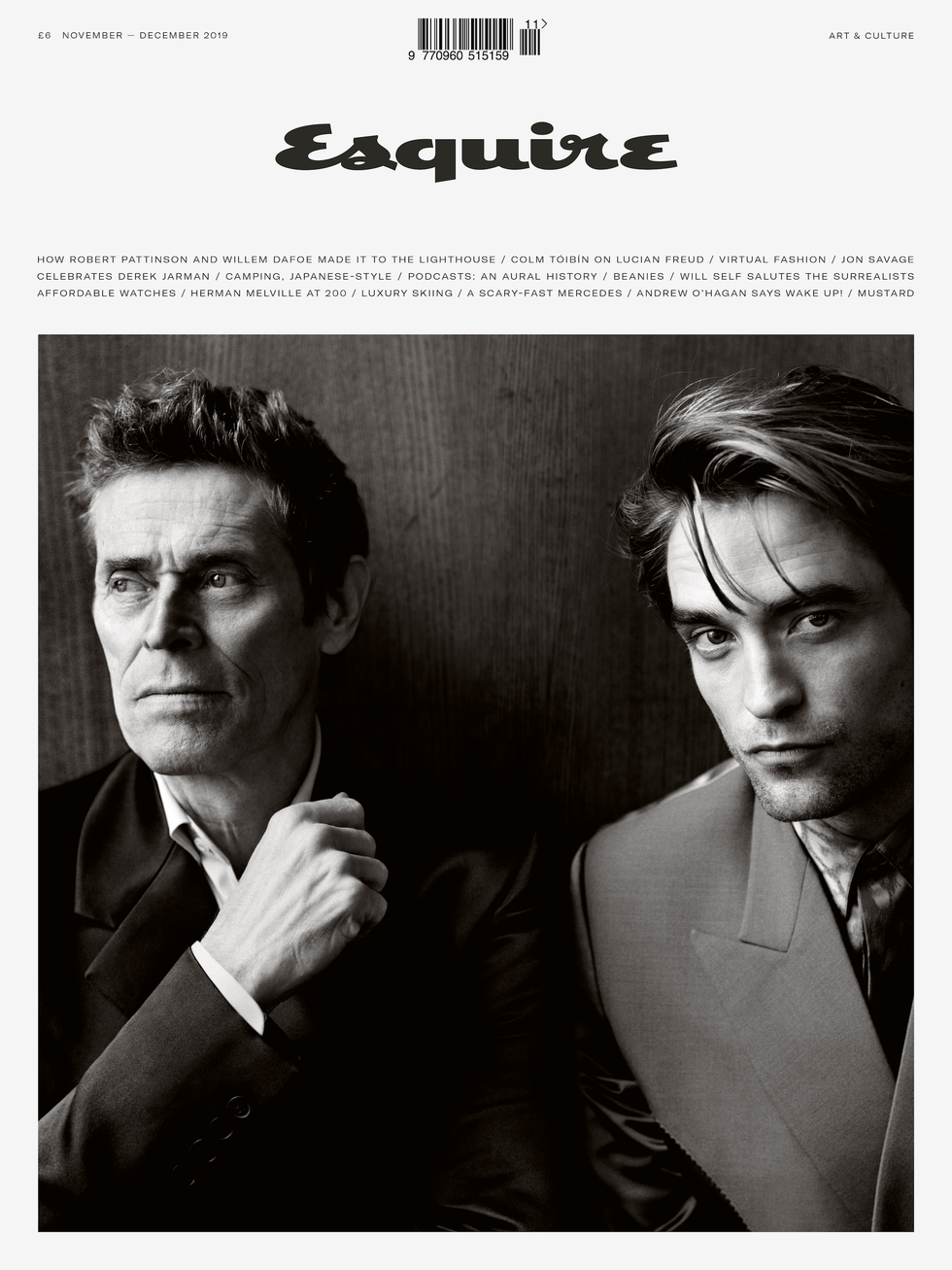

Now we see the men head-on, a striking dual portrait in high contrast black and white: a double exposure. They are wearing sailors’ caps, greatcoats, and hefting wooden trunks. One is younger, taller, moustachioed. The other, more deeply crevassed, sports a wild beard, out of which pokes a small wooden pipe, like Popeye’s. Theirs are, by any standards, remarkable faces, extreme faces, unyielding as rock yet sculpted with great delicacy, skin stretched tight over jutting bones: sharp noses, strong jaws, deep set eyes. And, oh, the cheekbones! And would you look at all those teeth?

Before anything else — before they are handsome faces, or expressive faces, or famous faces (they are all of those things) — these are photogenic faces. On first inspection they appear impassive, almost blank. And yet an air of foreboding is struck. The older man’s features are fixed in a roguish grimace. The younger man is wary, tense. These might be the faces of a father and son, or brothers separated by decades: hard, thin, stern faces, built for hard, thin, stern lives. Lives filled with mean disappointments, festering resentments, blood feuds. Here are men who have seen trouble before and will see it again. Maybe they’re looking for trouble. Maybe they’ve found it. Is this a dual portrait — or the portrait of a duel?

Whatever has thrown these men together in this place — fate, karma, the thirst for adventure, the desire for escape (in the case of the characters, but perhaps the actors, too?) or (in the case of the actors specifically) the need to stretch oneself artistically, or to challenge oneself physically, or the reputation of the director, or a really good script, or all of these things — one senses they are aware already, as they square up to the stinging reality of their circumstances, that they may have got more than they bargained for. What we can be sure of from the off: there will be weather. There will be conflict. And there will be acting.

The film is The Lighthouse, the second feature film from the 36-year-old American writer-director Robert Eggers, who made a stir with his debut, The Witch. Eggers, who is based in Brooklyn but grew up in rural New Hampshire, is a man possessed of a rare and creepy gothic sensibility. The Witch was an arthouse horror film, a twisted fairytale with the insidious power of a nightmare. It concerned a family of 17th-century puritans banished to the woods of New England, and it involved possessed children, birds pecking at human flesh, and an unholy bond with a goat. It cost $4m to make and earned that money back 10 times over, making Eggers not just a critical darling, but a coming man in commercial cinema.

For The Lighthouse, Eggers is reunited with A24, among other production companies, and with much of his crew from The Witch, including his director of photography, Jarin Blaschke, and composer Mark Korven, who between them do as much as anyone to set the eerie mood. His co-writer is his brother, Max Eggers. The actors were new to him.

Those faces that I have been at pains to describe, then, belong to Robert Pattinson and Willem Dafoe. They play lighthouse keepers on a wind-slapped, rain-lashed rock off the Atlantic coast of North America. The year is 1890. Pattinson is, or appears to be, Ephraim Winslow, the taciturn apprentice. “I ain’t much for talkin’,” he says early on — a statement, like so many in this film of shifting and unfixed identities, that turns out to be not entirely true.

Dafoe is Winslow’s irascible, peg-legged senior partner, Thomas Wake, an experienced “wickie” and a cruel taskmaster, obsessively enraptured by the beacon he tends. “The light is mine!” he declares, mad-eyed. Wake consigns Winslow to the bowels of the building, where the younger man stokes the fire and swabs the floors and nurtures his grievances, while indulging in some quite epic, mermaid-focussed masturbation. Winslow and Wake are to spend four weeks alone on the island before they are to be relieved. But when a storm blows in, the odd couple are stranded — maybe, or maybe not, because a violent act on Winslow’s part has brought down a curse upon them. Slowly, and then in spasms of ultraviolence, they unravel.

The Lighthouse is a twisted buddy movie, a surreal black comedy, a psychological thriller set at the hysterical pitch of Grand Guignol. It was filmed in the spring of 2018 on sound stages in the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, on Canada’s Atlantic coast, and on location on the tiny fishing community of Cape Forchu, nearby. (“People tend to spend up to 45 minutes here,” Google Maps tells us of Cape Forchu. This fact might, or might not, amuse the filmmakers who spent weeks there, battling Biblical conditions. “It snowed in May,” notes Dafoe.)

With the exception of the Moldovan model Valeriia Karaman, who makes a number of brief, though memorable, appearances in her debut film, Pattinson and Dafoe are the only members of the cast, and their seesawing power struggle is the film’s entire focus, with point of view switching sides like a sail boat’s boom in a storm. Its success or failure rests heavily on their shoulders.

Pattinson and Dafoe are big stars, both. They are also men from different generations, different backgrounds, different countries and traditions. The Lighthouse was not an easy film to make for a number of reasons — the remote location, the raging weather — but not the least of the filmmakers’ challenges were the contrasting approaches of the two actors.

“They really did have incredible chemistry on screen,” director Eggers tells me on the phone, “but it was chemistry through tension. I know there’s been discussion about their different acting techniques and the trying conditions on set…” He pauses. “That couldn’t have been better for the movie.”

If you happened to be out and about in Halifax, in the early spring of 2018, you may have noticed a slender young loner stalking the streets day after day, muttering to himself. Noticed him, and felt concern for his emotional wellbeing. Had you followed him, and listened closely, you might have heard the same words repeated over and over again, in a gravel-voiced near-grunt: “Woyt poyn, woyt poyn, woyt poyn…” Come again? “Woyt poyn, woyt poyn...”

“White pine,” the slender young man enunciates into my voice recorder, 18 months on, in the accent of a nicely brought-up southwest London boy, rather than a 19th-century working man from a highly specific part of Maine. White pine — I’m sorry, woyt poyn — is one of the trees which his character lists when telling his colleague of his past misadventures as a lumberjack. Pattinson developed the accent with the help of a dialect coach and by speaking to a contemporary Maine lobster fisherman on the phone. “It’s one of those accents where if you say one syllable wrong it’s suddenly Jamaican, or something,” he says. “So it took ages.”

Pattinson arrived early in Halifax, before his director and co-star, to psych himself into the role of the saturnine Ephraim. Having approached Eggers after seeing The Witch, in the hope that they might at some point work together, Pattinson had declined the director’s first suggestion, for a part in a more conventional, mainstream film that the director was then developing.

“He said he was only interested in doing weird things,” Eggers says. “So when The Lighthouse came around I said that if he doesn’t find this weird enough, I guess we’ll never work together.”

It’s true, Pattinson says, that at that time, in 2016, he “wanted to do the weirdest stuff in the world.” (Mission accomplished, Rob!) Still, he spent a good deal of time agonising over whether or not to take the role in The Lighthouse. “I remember reading it and I thought it was very funny, but I was also thinking, ‘I don’t understand how the tone would work?’”

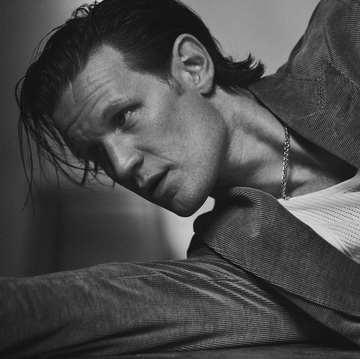

When Dafoe signed on, Pattinson was excited. “I knew Willem could bring that kind of anarchic energy,” he says, “but I really didn’t know how I would do it at all.” Dafoe, he says, in one of his many moments of self-effacement, “has one of those faces where he can literally sit in any room in the world, doing almost nothing, and it’s fascinating to watch. Whereas I sort of blend in with the chair I’m sitting on.”

Before filming began, the pair spent a week in rehearsals. Pattinson dislikes rehearsing, preferring to do his experimenting on camera. “It was very, very frustrating,” he says. “I just couldn’t achieve what they wanted me to achieve in that room. Robert [Eggers] was getting furious with me because I was just sitting there, completely monotone the whole time. He could not stand it.” Pattinson tells the story with no rancour whatsoever. He knows it sounds funny, but it wasn’t at the time. “I just don’t know how to perform it until we’re performing it. By the end of the week, I’m thinking, ‘I’m going to get fired before we’ve even started’. I definitely feel like, with the rehearsal period, we were quite angry with each other by the end of it. Literally, we’d finish for the day, I’d fucking slam out the door and go home.

“I knew that there was diminishing expectations of me throughout the week of rehearsals,” he says. “I definitely became an underdog. They’re like, ‘Wow, this was a big mistake. He’s really shit.’”

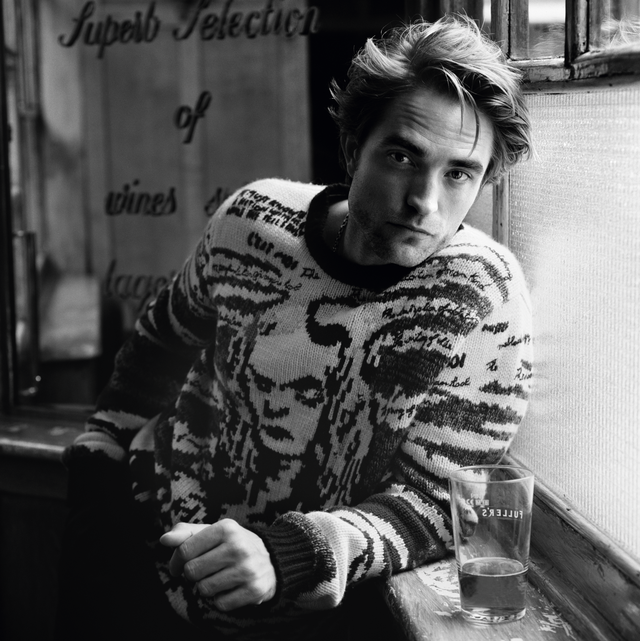

Pattinson and I talk on a sweltering August morning, in the comfort of a private members’ club in west London, near the flat he’s rented for the summer on Airbnb. (He’s in town to shoot Christopher Nolan’s new sci-fi spectacular, Tenet, about which he is permitted to tell us, with fulsome apologies, precisely nothing.) Rather than swigging kerosene and chaining tobacco, as in the film, he orders a banana smoothie, and when he’s finished that, an apple juice. Occasionally he sucks on a Juul.

Pattinson is 33. He grew up in affluent Barnes, the son of a dealer in vintage cars and a model booker. More or less untrained — unless you count some teenage am-dram — at 19 he was cast as Cedric Diggory, the hero’s doomed frenemy, in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. But his Hollywood breakthrough arrived in 2008. Twilight was a teen B-movie, but it became a pop cult phenomenon, spawning four sequels of diminishing charm, making an otherworldly $3.3bn worldwide and creating megastars of its leads, Pattinson, who played a sexy vampire, and Kristen Stewart, who became his girlfriend on screen and IRL, as they say, before, in an unseemly frenzy of prurient salivating, she became his ex-girlfriend.

While for some he may always be the pallid tween heartthrob, in the six years since the final instalment of Twilight, Pattinson has worked hard to reinvent himself. His post Young Adult years have been cussedly uncommercial and impressively adventurous. In that period, Pattinson has worked with some of cinema’s most fêted directors: David Cronenberg, Anton Corbijn, James Gray, Werner Herzog, the Safdie brothers. Most recently, he was an intergalactic castaway in High Life, an enjoyable, if bonkers, dystopian sci-fi from the French director Claire Denis.

“Even in the Twilight years I never said, ‘Oh, he’s just a pretty boy,’” says Robert Eggers. “I always thought there was something interesting about him. I could tell that he wanted to be a great actor. And in the past years it’s been very clear that he is.”

The attraction of more avant garde or outré material, Pattinson says, is it allows him to let rip in a way he never could in real life. Pattinson compares the experience of acting in a film like The Lighthouse with joyriding. “A lot of the movies I’ve done recently, you literally feel as if you’ve stolen a car and you’re kind of careening through stuff.” (Such are the fantasies, perhaps, of a boy who grew up with a father who imported American sports cars for a living.)

In person, Pattinson is a mild-mannered English actor, albeit a slightly eccentric one. On set, however, “because you’re playing a mad person, it means you can sort of be mad the whole time. Well, not the whole time, but for like an hour before the scene.”

What does he mean by being mad? “You can literally just be sitting on the floor growling and licking up puddles of mud.”

This sounds figurative. He really means it. On The Lighthouse, in the scenes in which his character is meant to be drunk on kerosene (there are quite a few of them), he was “basically unconscious the whole time. It was crazy. I spent so much time making myself throw up. Pissing my pants. It’s the most revolting thing. I don’t know, maybe it’s really annoying.”

It’s hard not to speculate that yes, it might be really annoying. “There’s a scene,” Pattinson remembers, “where Willem’s kind of sleeping on me and we’re really, really drunk and I felt like we’re completely lost in the scene and I’m sitting there trying to make myself gag and Robert [Eggers] told me off because Willem’s looking at him going: ‘If he throws up on me, I’m leaving the set.’ I had absolutely no idea this whole drama was unfolding.”

In some ways, Pattinson concedes, all this acting out is a reaction to his terrifying early super-fame. He speaks of himself in the second person when talking about it. “For a long time you’re very self-conscious in the street. You’re hiding a lot, so [on set] you have an excuse to be wild. It’s like being an adrenaline junkie. And also, when you don’t know how to do something, why not just run headfirst into a wall? See what happens. I haven’t got any other ideas.”

On The Lighthouse, he spun in circles before each take, to make himself off-balance. He placed a stone in one of his shoes, to increase the already considerable physical hardship. He can see — from my disbelieving laughter, apart from anything else — that all this strikes non-actors as funny, even preposterous. It may be that it sounds this way to some actors, too.

The most famous story (possibly apocryphal) of an encounter between an adherent of the Method — in which actors don’t so much pretend to be someone else as try to temporarily become them — and a more traditional, outside-in actor, who puts on costume and makes believe, is Laurence Olivier’s withering put-down of Dustin Hoffman, when they were working together on John Schlesinger’s Marathon Man. At some point, Hoffman, a graduate of the Actors Studio, confided in the great English Shakespearean that, in order to bring the correct verisimilitude to a scene in which his character has not slept for three consecutive nights, he had forced himself to stay awake for the same period. “My dear boy,” Olivier is said to have smoothly replied, “why don’t you just try acting?”

Eggers says that any suggestion of that kind of relationship between Dafoe and Pattinson is wide of the mark. “The idea that Dafoe is outside-in and Rob is this method actor, that’s not the case. I think maybe they lean the tiniest bit into those directions but they’re both combinations of things.”

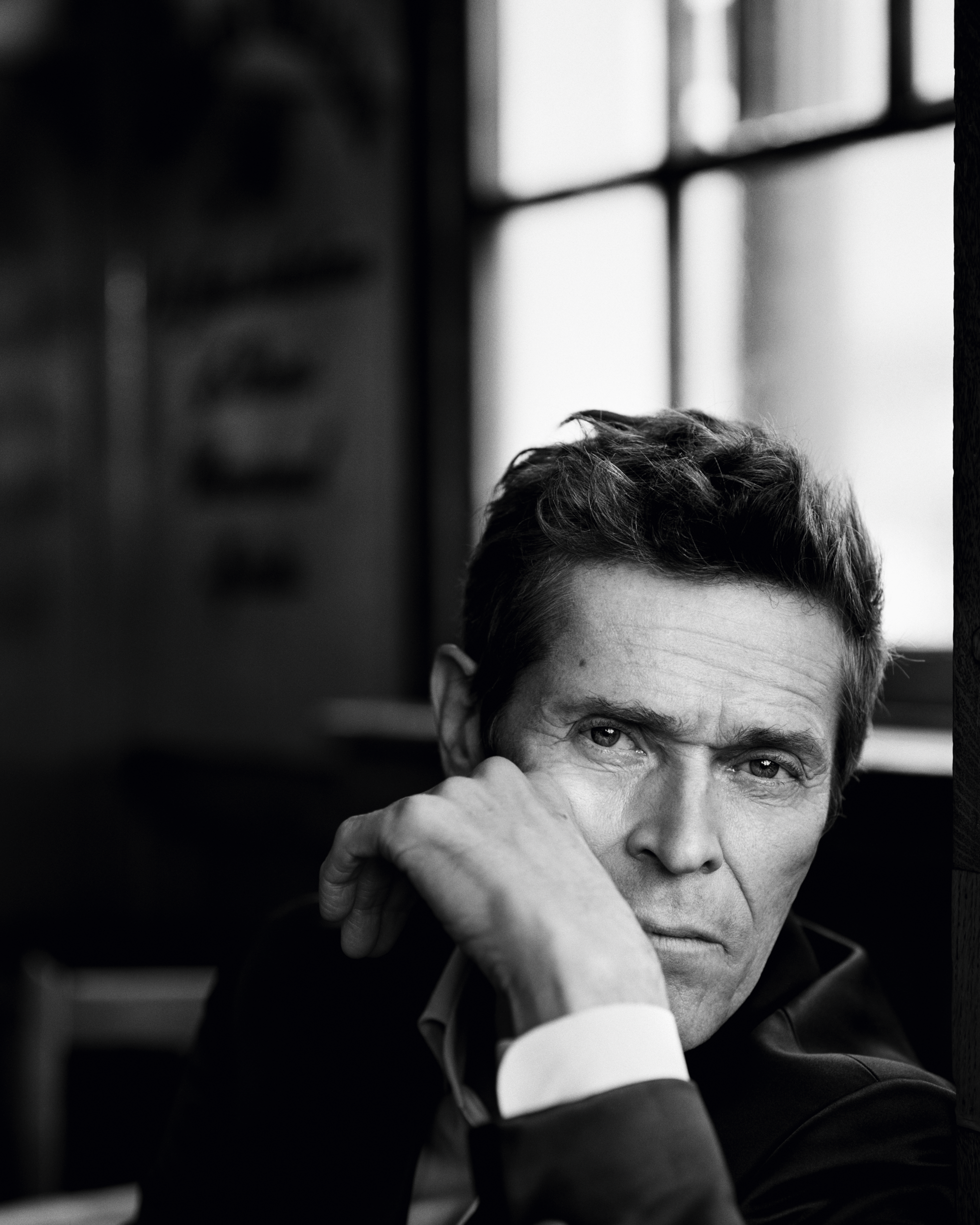

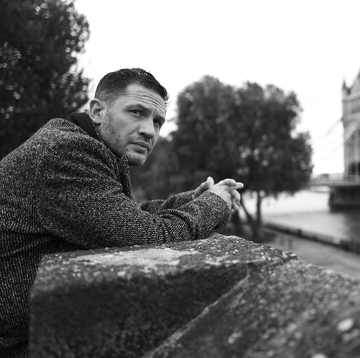

Three weeks before my interview with Pattinson, I collected Willem Dafoe from the Coach and Horses, the pub on Greek Street where Alasdair McLellan took the photos on these pages, and walked with him, through a balmy Soho afternoon, to a members club on Dean Street, where we took a banquette in a back corner and doubled our bodyweights with sparkling water.

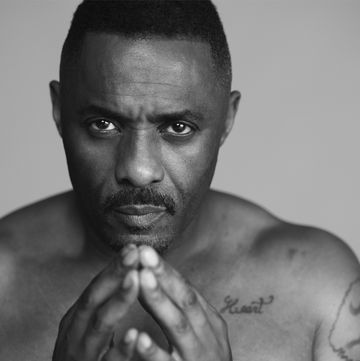

In discharging my duties for this publication and others, I have walked through busy streets with numerous famous people, many with more obvious mainstream commercial appeal than Willem Dafoe, and observed them go unnoticed. At 5’9”, compact, lean and wiry, with those sunken cheeks and his trademark gap-toothed grin, he is not a big man, but so unmistakable is he, so little does he resemble anyone else, and so rare is it, even in Soho, to see a film star of his distinction — not an everyday celebrity, but a genuine, under-the-radar screen legend — that people stare open-mouthed as he passes. Inside, the owner of the place, usually a model of civilised discretion, comes over to introduce himself and express his admiration. While Dafoe is in the loo, our waiter tells me I’ve made his month by bringing Dafoe in. In short, people are impressed by Willem Dafoe, as well they might be. (Was it intimidating, working with Dafoe? I asked Pattinson. “Yes,” he said. As in: What do you fucking reckon?)

Raised in the city of Appleton, Wisconsin, the seventh of eight children born to a nurse and a surgeon, he began his career in experimental, avant-garde theatre in the fiery crucible of downtown Manhattan in the late Seventies, a fabled time of artistic ferment. He broke into movies in the Eighties (Kathryn Bigelow gave him his first screen role, as a biker in The Loveless), and by the time he was 30 he was an established star, nominated for an Oscar in 1985 for his searing performance in Platoon, Oliver Stone’s sensational reckoning with the Vietnam War: his first, and by no means last, indelible screen death.

Dafoe is 64. At the age Pattinson is now, he was playing a very human Jesus Christ, for Martin Scorsese, in The Last Temptation of Christ. He’s been a lubricious sex criminal, the unforgettable Bobby Peru, for David Lynch, in Wild at Heart. He has made five films with Paul Schrader, three with Wes Anderson. He was the Green Goblin in three Spider-Man films. The voice of a fish in Finding Nemo. Last year, he was nominated for an Oscar for his performance as Vincent Van Gogh, in Julian Schnabel’s gorgeous At Eternity’s Gate, for which he learned to paint. The year before that he was nominated for an Oscar for playing the motel manager in The Florida Project, another performance of great warmth, delicacy and restraint.

Dafoe’s is not the CV of an actor who denies himself challenging experiences. Neither is he work-shy. Imdb.com lists upwards of 130 film credits. Dafoe takes issue with that total. “Some of those are cameos, some of those are not very substantial things.” And then immediately concedes defeat. “I guess they aren’t including smaller films and experimental films so… I mean, OK, it’s probably 130.”

In any case, I tell him, he works a lot. “I always say to myself, ‘Jesus, you’ve made a lot of movies’. But I still have this sense of every time it’s a little different. So I don’t feel like the old hand. I roll up my sleeves, if I’m asked to roll up my sleeves.”

I wonder if, as the senior partner in a film like The Lighthouse, he is ever moved to offer younger co-stars the benefit of his wisdom? “No. I don’t ever try to step on their toes or give them any advice, or have any ideas for them. I can only participate in the scene. But I’m very clear, I mean I think I am.” He smiles his gap-toothed smile. “Maybe I’m bullshitting myself. Go and ask Pattinson if I ever gave him advice. No! I wouldn’t give anybody advice. Even if they asked for it. I’d probably try to be sweet because everybody’s gotta find their own way. I gotta find my own way.”

In conversation, Dafoe is affable, expansive, relaxed. He is a great talker and an extraordinarily elegant and expressive mover, using his arms and hands to tell his stories, testament to his years on stage, working alongside dancers.

He is worldly and sophisticated, comfortable in his skin. He lives between Rome, where he shares a house with his wife, the Italian film director Giada Colagrande, and New York City. He once described himself as the boy next door, “if you live next door to a mausoleum”.

Dafoe shares with Pattinson a profession and a certain physical resemblance — “Noses and cheekbones and teeth, if you know what I mean,” as Eggers puts it. There perhaps the similarities begin to thin. Dafoe is confirmed and determined in his opinions where Pattinson is hazy and undecided. Pattinson affects a very English, “who-me?” klutziness; he vibrates at a high frequency, gives off a nervous energy. Dafoe is cool and cerebral.

As with Pattinson, his involvement in The Lighthouse came about when, having seen The Witch, he asked his representatives to approach Eggers, with the idea that they might work together. “Happily, he was aware of my work,” says Dafoe. (Can there be a lover of cinema alive — let alone a film director — who isn’t?)

He immediately responded to The Lighthouse. “When I read a script, I say, ‘Do I want to do these things? Do they resonate with me? Will they create an adventure that takes me to a place that I’m curious about?’” With The Lighthouse, the answer was, “Absolutely. It’s a beautiful script, very musical, the text is gorgeous. And I’m enough of a nature boy that I knew that we were gonna be in full-on nature. I’m enough of an athlete to know that there were gonna be some physical things to do. And I’m enough of an actor to know that it would be challenging to do this very full-blown character but to give him a reality that really gets under your skin.”

“We both were working hard, in really tough conditions,” Dafoe says of his interactions with Pattinson. “It’s not like we hung out in between takes, joking with each other. It was demanding enough, and the weather was shitty enough that you did your thing, and then you went home. I’m not complaining. It was fun. But when you go home after 12 hours and you’re soaking wet and you’re cold all day, last thing I wanna do after being with those guys all day was to hang out with them and have some drinks.”

His relationship with the material seems a good deal less fraught than that of his co-star. I’m not convinced, for example, that he went through an agonising period of doubt over whether he’d be good enough to pull it off.

When I’d asked Pattinson to tell me about his character, aware of the ickiness of the question — “Who is Ephraim Winslow?” — what followed was five to seven minutes of wracked explication, with much running of hands through hair and pulling of pained faces. “What’s it called when you shine a light through something and it creates a spectrum? Yeah, a prism.” Pause. “It’s an emotional impetus trying to force itself into a brain that doesn’t have the mechanism to…” Pause. “He doesn’t know who he is at all. He’s having an identity crisis. I mean, he’s fucking psychotic.” Pause. “I’m terrible at this question.”

When I ask Dafoe the same thing — “Who is Thomas Wick?” — without hesitation he says: “Thomas Wick is me if I was Thomas Wick.” And he raises a sardonic eyebrow.

Asked to elaborate, he continues: “I’m not there to interpret something or to tell you about a character. I’m there to have an experience and that experience will inform the character. You do the research for an accent, you do the research to imagine where he came from, things like that. But you aren’t thinking about those things when you’re playing the scene. You’re not saying, ‘When I reach for that glass, I’ve gotta think about his early days, be wistful’. Or whatever. You just aren’t. Most of the choices are made just by what’s going on. I think I mostly concentrated on the text and being there, and how to smoke that pipe well, and learning how to knit, and how to carry an axe. Things like that.”

“Willem’s really good at talking about acting,” notes Pattinson, admiringly. “He is very clear about what his technique is.”

Pattinson, perhaps, still has something to prove, to himself if to no one else. Dafoe, not so much. He uses the word “fun” a lot, to describe his experiences, even on the most gruelling productions. And he does seem to be having lots of fun, relishing the opportunity, for example, to pretend to be a crazed 19th-century lighthouse keeper. Think of the quintessential salty old seadogs of high art and low — the Captains Ahab, Haddock, Birdseye, the Captain from The Simpsons (“Aye, ’tis a sugary brine!”) — and now imagine one of them played by one of the most distinguished screen actors anywhere, with the wind in his sails. “You’re fond of me lobster!” he shouts at Pattinson, in an outburst to rival Daniel Day-Lewis’s deathless cry of, “I drink your milkshake!” from There Will Be Blood.

It’s quite an extreme kind of fun, I suggest. Most of us are content to go to the pub, or put on the TV. “I shouldn’t make this comparison,” Dafoe says, “but recently I watched Free Solo and Alex Honnold [the death-defying free-climber, subject of that documentary] talks about fun. What he’s talking about, it’s not fun, but it’s pleasure. He found a way to connect with something that he loves and something that is meaningful to him and something that gives his life purpose. That’s what I have with performing, and sometimes it goes south, sometimes it’s silly, sometimes, because of the collaborative nature of it, you can do beautiful things, you can do horrible things, but as long as you know why you’re doing them, for yourself, you’re protected.”

It’s not, he says, when I kid him about not having made many cosy domestic romances, that the part has to be physically challenging, “or that I think that you gotta be reckless, or dangerous. It’s not that. It’s really curiosity, and wonder, and learning stuff. If I’ve learned nothing else, it’s about the doing, it’s not the showing. That’s the most fundamental thing about performing. I abhor this expression, ‘nailing it’. There’s no such fucking thing. It’s wide open.”

It became known as the tragedy of Smalls Lighthouse. In 1801, two lighthouse keepers, Thomas Griffith and Thomas Howell, one older, one younger, found themselves stranded by a storm on a tiny, rocky island off the coast of Wales. Griffith fell ill and eventually died. For four months, as a number of rescue attempts floundered, Howell was marooned with the remains of his partner. By the time Howell was rescued he had lost his mind, driven mad by the isolation and the cold and the hunger and the horror of being left alone with a corpse. In future, no fewer than three men would be permitted to crew a British lighthouse at any one time, to prevent such a thing happening again.

The Lighthouse tells a different story, but the tragedy of Smalls Lighthouse informed the earliest version of the script, which was conceived and written by Max Eggers, Robert’s brother. (In 2016, a film by a Welsh director, Chris Crow, also called The Lighthouse, was based more closely on the tale of Griffith and Howell.)

“I was envious of such a great idea,” Eggers says, of his brother’s project. When the studio projects he was working on didn’t come off, he asked Max if he could have a go at The Lighthouse. With Pattinson and Dafoe on board, it came together quickly. The finished film will be released in America in October, but won’t wash up on British shores until January, along with the many other films competing for attention, and awards, in the busy winter season.

It’s not the only Willem Dafoe film on its way to us. He’s in Motherless Brooklyn, Edward Norton’s long-awaited adaptation of the Jonathan Lethem novel. He’s the title character in Abel Ferrara’s Tommaso, about an American artist living in Rome. The Last Thing He Wanted, from a Joan Didion novel, with Anne Hathaway and Ben Affleck. Another Wes Anderson ensemble movie, The French Dispatch. And a Disney movie called Togo, about a brave dog.

It’s by no means the only Robert Pattinson film on its way to us, either. There’s The King, David Michôd’s retelling of Henry V, with Timothée Chalamet in the title role and Pattinson as the French Dauphin. The Devil All the Time, an adaptation of Donald Ray Pollock’s lurid gothic novel, in which he plays a wicked evangelical preacher in the Deep South of the Fifties. Waiting for the Barbarians, from a JM Coetzee novel, with Johnny Depp and Mark Rylance. The Stars at Noon, for Claire Denis again, based on a Denis Johnson novel.

Meanwhile, he’ll be preparing for his most high-profile mainstream role since Twilight, as the Caped Crusader himself in The Batman. “It’s kind of insane. I was so far away from ever thinking it was a realistic prospect. I literally do not understand how I’ve got it, at all,” he says. The rest of us might reflect that he’s got it because he is one of the most watchable and unpredictable male stars currently working. And, as Dafoe notes, he certainly has the jaw for it.

The Lighthouse was rapturously received at Cannes. Pattinson says he was pleasantly baffled by the response on the Croisette, where the audience seemed particularly tickled by the film’s comedic elements. “I thought it was serious, and dark, and kind of sad,” he says of his own first impression, when he watched the film in Los Angeles. “I was quite shocked by it.”

Dafoe is zen about how the film will be received, as he seems to be about so many things. This movie won’t define either actor’s career. And the director, indisputably gifted, will go on to other things. But it was an experience none of them will likely forget.

“I think it’s a beautiful film,” Dafoe says. “Terribly goofy, too.”

The Lighthouse is released in cinemas on 17 January

Styling: Ellie Grace Cumming

The Esquire 'ART & CULTURE' issue is out now. Subscribe here.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox