“It could be really boring,” Ruth Wilson says, cheerfully, of the extraordinary feat of theatrical endurance she is shortly to attempt. She speaks with the confidence of someone who knows that the “it” to which she refers is, in fact, quite unlikely to be really boring. “No,” she corrects herself, “I anticipate it won’t be.”

Cool, soignée and — given the circumstances — almost eerily composed, Wilson is perched on a banquette at a Soho members’ club, sipping sparkling water from a crystal tumbler and calmly explaining her reasons for signing up to what must be the most gruelling job any prominent actor will undertake this year, Tom-Cruise-does-his-own-stunts and Kendall-from-Succession-sleeps-in-character included.

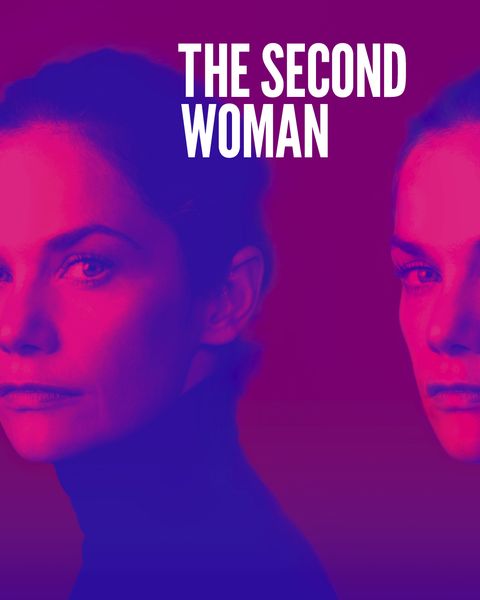

It’s a Wednesday evening in March, and not that you’d know it but Wilson is less than two months away from being dumped — cruelly, not so cruelly, and who the hell knows? — by precisely 100 men, one immediately after another, in The Second Woman, a one-night-(and-day)-only production, because two-nights-(and-days)-only would presumably contravene the UN convention against torture, fully 24 hours in duration, with only brief pauses for the leading lady to reset the stage, take comfort breaks and, one imagines, quietly go to pieces.

As soon as she was approached about it, Wilson says, “I was like, ‘Yes!’ instantly. I just thought it sounded fucking mad. And I’m quite interested in things that feel mad. Probably because I am a bit mad.”

I tell her that, talking to her about it, I feel as one does when an acquaintance says they’ve signed up for an ultramarathon: a mixture of awe and bafflement. I mean, hats off and high-fives all round, but why don’t they just go for a nice jog, like the rest of us?

“Yeah, or do a normal play?” Well, yes: why doesn’t she just do a normal play? “But I’ve done a normal play before! To me, this is a physical challenge, and an emotional challenge. I am interested in what I will go through and how I will survive it. Am I going to completely lose my shit, lose my professionalism? It’s all possible. I mean, it’s going to be weird! Repeating the same scene? Over and over and over again? It’s going to feel like a mad nightmare.”

Not that this is some frivolous, Record Breakers-style stunt. The Second Woman, says Wilson — and in this she is backed up by the worshipful reviews of earlier productions (The Guardian: “a stunning exposure of gendered power relations and emotional coercion”) — is an investigation of the function and meaning of performance, on stage and in life.

Wilson’s character is called Virginia. The 100 men are all different versions of Marty. They are partners, or lovers, or somehow romantically involved. He enters and tries to end the relationship. When she seeks reassurance, he is unwilling, or unable, to give it. The scene lasts seven minutes and each time it is repeated it follows the same short script. It is simultaneously filmed on multiple cameras and projected onto a screen. Audience members can choose to watch edited close-ups or the unmediated action on stage, or, most likely, switch between the two.

The Second Woman was created by Nat Randall and Anna Breckon, inspired by John Cassavetes’ 1977 film Opening Night, about a troubled actress preparing for a Broadway premiere. It was first performed in Melbourne, Australia, in 2016. Since then it has played in Toronto, Taiwan and New York, each time with a local actor taking the lead role, and a century of male volunteers (a handful of professionals, the rest all amateurs) lining up to put their own spins on giving its protagonist the elbow.

Presumably each man in the London production, which will play at the Young Vic, from 4pm on Friday 19 May until 4pm the following day, will have his own motivation for appearing on stage attempting to end a relationship that never actually occurred with a woman who will have the considerable advantage of being played by a multi-award-winning star while they, for the most part, might as well have walked in off the street. Which, in almost all cases, they will have. None will have rehearsed the scene with Wilson. The vast majority will never have met her.

“It’s completely random,” Wilson says. “When someone comes on, I will never have seen him before in my life. And it’s not the same safe space as when [a trained actor] comes on. Someone who isn’t an actor is bringing so much more of himself, probably. And that makes for a weird dynamic. It’s not a performance, as such. It feels more real. They might have a plan for what they’re going to do. But you never know how someone’s going to feel, and how they will interact with me once we’re on stage together.

“The things that excite you as an actor are moments of spontaneity,” Wilson says. “Going into TV or film or even a play you can prepare meticulously, but the things that make you feel alive are when it’s something surprising or shocking, when someone does something different. You’re always looking for something that feels real, even in a constructed environment.

“In this,” she adds, “there’ll be artifice, obviously, in the sense that some of my moves will be the same every time, and we’ve been given lines to say. But alongside that will be things that feel radically real, with no pretence. And I think after a few hours, it’ll all be up for grabs.”

A breathless talker, with a pronounced ability to cackle at herself — a quality, one feels, that might stand her in good stead in the early hours of 20 May — Wilson is an accomplished and garlanded screen star, and no stranger to emotionally fraught material. She broke through as Jane Eyre, on TV, in 2006. Subsequently, she was the seductive psychotic who mesmerises Idris Elba in Luther; the grieving waitress dangerously entangled with Dominic West’s older man in The Affair; the alarming Mrs Coulter in the recent adaptation of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials.

A south Londoner originally from Surrey, at 41 she is also one of our finest stage tragediennes. Wilson has been through the wringer in some of the most demanding roles in the canon: the traumatised prostitute in Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie; brutalised Stella, wife of the bullying Stanley, in A Streetcar Named Desire; the doomed heroine of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler; Cordelia in King Lear; a stricken physicist in Constellations, on Broadway. Last year, in London, she was the heartbroken caller in Jean Cocteau’s devastating monologue The Human Voice, working again with her Hedda Gabler director, the ubiquitous Ivo van Hove. It’s not a CV that’s heavy on dizzy romcoms.

But still… The Second Woman supplies suffering of a different order: her own, rather than her character’s. Not to mention the audience’s, especially if anyone should choose, as has apparently happened in previous productions, to stay for the full 24 hours. “It’d be lovely if someone did,” she says. “Because they might be the only person who witnesses the whole thing. I think most people will probably stay for a few hours, but I’m hoping they’ll leave and then want to come back. Come at 8pm, stay for two hours, go home, wake up on Saturday morning and go, ‘Fuck! She’s still there!’ I actually think the audience will share something among themselves; they’ll be connected to each other. They’ll recognise someone else who was also there at 2am.”

She suspects they will share something special with her, too. “As I go through the night I’m going to be less able to have some sort of filter,” she says. “The audience are going to see that. I won’t be able to hide it. I think I’ll have more communion with the audience than with the men opposite me. They’re only going to be there for a few minutes, but the audience are with me; it’s their space, too. I’m intrigued by whether it will break down barriers between us. I want to get to the point of being absolutely unselfconscious on stage.”

So far, she says, she has done no training whatsoever. “Two weeks before I’ll have a session with an actor, to choreograph it,” she says. “Because there are set moves which I will have to guide. So I’ll rehearse those. And I will have some rehearsals with other men, who aren’t going to be there on the night, just to anticipate a few reactions. So if someone completely forgets their lines, I’ll have a few tools for how to help that person in that moment. But that’s kind of it.”

I wonder how she is preparing for the physical aspect of the endeavour. Is she in some sort of sleep-deprivation conditioning? The answer is no. “I dunno!” she says, clearly revelling in the uncertainty. “Sometimes I think, Maybe just do it? I think the adrenaline will get me through. That and Red Bull.”

She’ll have a 15-minute break every two hours. “That’ll be a loo break,” she says. “Cigarette, maybe? Meditate? Do some push-ups? Jump on the spot? Ten-minute snooze? All those things? I think I’ll just have to be really alert to how I feel in the moment, and those 15 minutes are going to be precious.”

And then, back to the stage to be chucked again, by yet another anonymous bloke.

“In Australia,” she says, “they were saying that the men were almost enjoying being nasty. But I don’t know, maybe British men are slightly different to Australian men? And then when they did it in Asia it was phenomenally different, and then different again in America. Because the dynamics between genders are so different in different cultures. The etiquette, the language, the respect or lack of respect between men and women: totally different. And I think it’ll be different again, here.

“You know,” she says, “Brits have got a lot of eccentricities. We’re still quite buttoned up on the surface, but underneath we’re pretty weird, and I hope some of that’s going to come out.”

One thing about us Brits on which everyone seems to agree: we produce excellent actors. "I always think when people say that,” Wilson says, “the subtext is that it’s because Brits are constantly performing. We are covering up our true feelings and pretending to be unaffected. We live in subtext the whole time.”

Is there a difference between performing in life, and performing on stage and screen? "I dunno,” she says. “Maybe we’ll find out.” ○

‘The Second Woman’, co-produced with LIFT, will run at the Young Vic from 19-20 May; youngvic.org