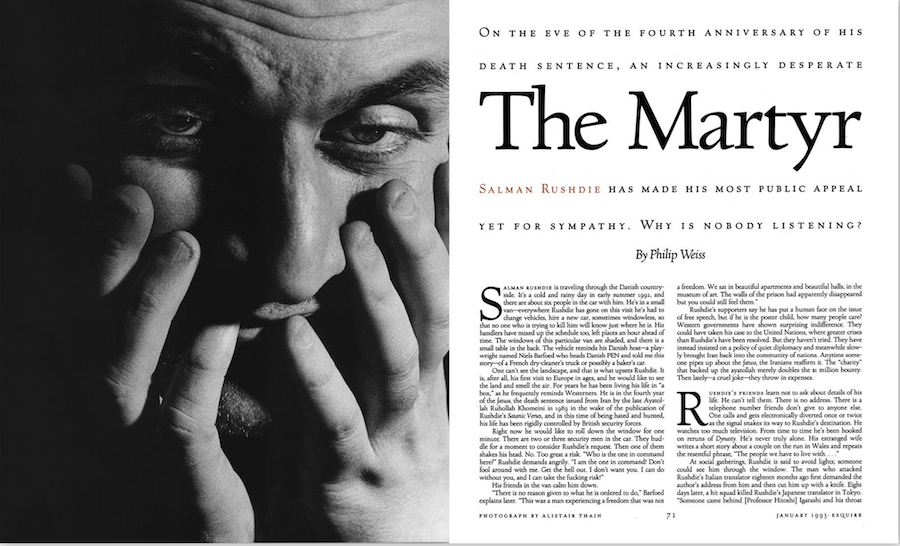

This article originally appeared in the January 1993 issue of Esquire US. To read every Esquire US story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

Salman Rushdie is traveling through the Danish countryside. It’s a cold and rainy day in early summer 1992, and there are about six people in the car with him. He’s in a small van—everywhere Rushdie has gone on this visit he’s had to change vehicles, hire a new car, sometimes windowless, so that no one who is trying to kill him will know just where he is. His handlers have mixed up the schedule too, left places an hour ahead of time. The windows of this particular van are shaded, and there is a small table in the back. The vehicle reminds his Danish host—a playwright named Niels Barfoed who heads Danish PEN and told me this story—of a French dry-cleaner’s truck or possibly a baker’s car.

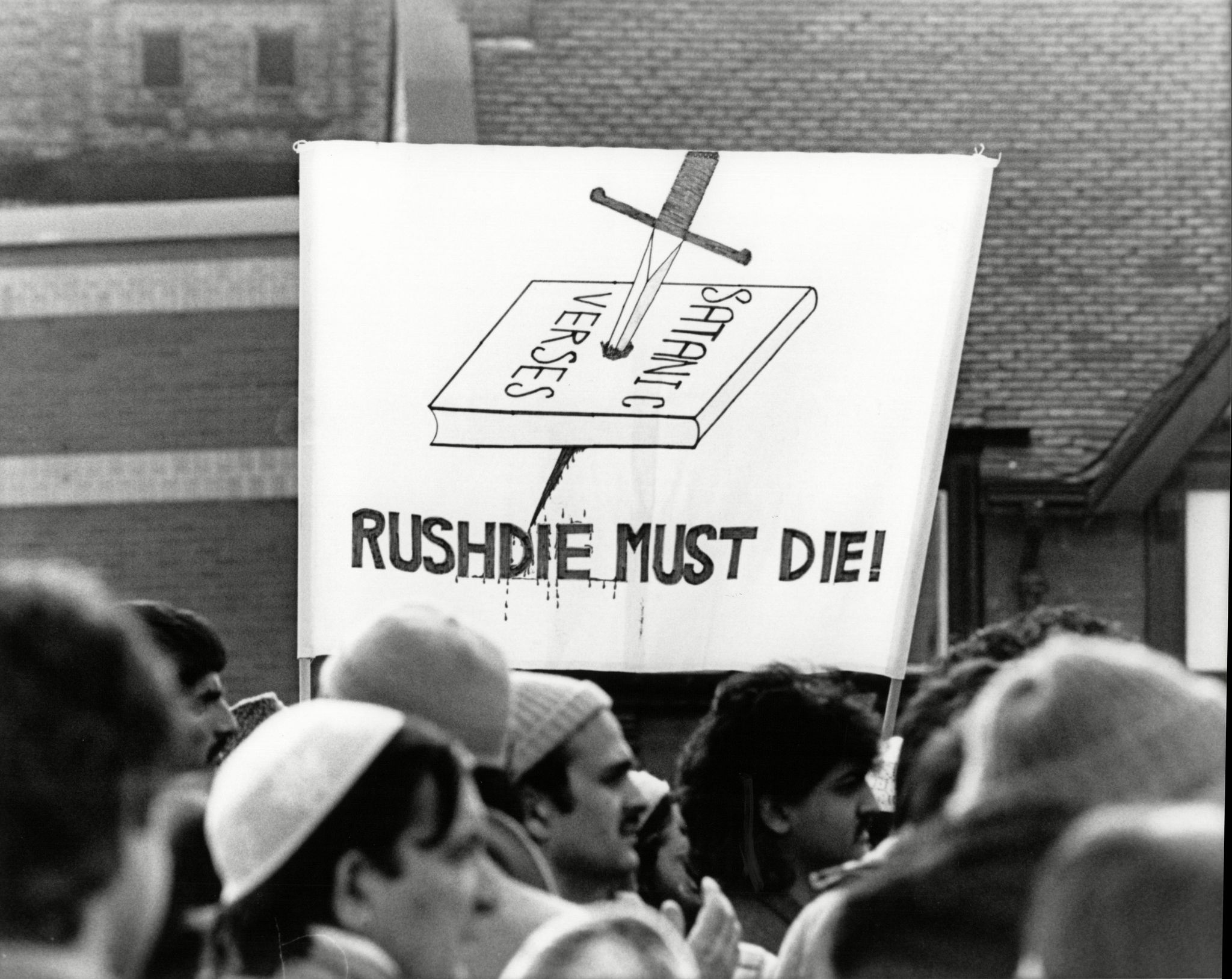

One can’t see the landscape, and that is what upsets Rushdie. It is, after all, his first visit to Europe in ages, and he would like to see the land and smell the air. For years he has been living his life in “a box,” as he frequently reminds Westerners. He is in the fourth year of the fatwa, the death sentence issued from Iran by the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989 in the wake of the publication of Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, and in this time of being hated and hunted, his life has been rigidly controlled by British security forces.

Right now he would like to roll down the window for one minute. There are two or three security men in the car. They huddle for a moment to consider Rushdie’s request. Then one of them shakes his head. No. Too great a risk. “Who is the one in command here?” Rushdie demands angrily. “I am the one in command! Don’t fool around with me. Get the hell out. I don’t want you. I can do without you, and I can take the fucking risk!”

His friends in the van calm him down.

“There is no reason given to what he is ordered to do,” Barfoed explains later. “This was a man experiencing a freedom that was not a freedom. We sat in beautiful apartments and beautiful halls, in the museum of art. The walls of the prison had apparently disappeared but you could still feel them.”

Rushdie’s supporters say he has put a human face on the issue of free speech, but if he is the poster child, how many people care? Western governments have shown surprising indifference. They could have taken his case to the United Nations, where greater crises than Rushdie’s have been resolved. But they haven’t tried. They have instead insisted on a policy of quiet diplomacy and meanwhile slowly brought Iran back into the community of nations. Anytime someone pipes up about the fatwa, the Iranians reaffirm it. The “charity” that backed up the ayatollah merely doubles the $1 million bounty. Then lately—a cruel joke—they throw in expenses.

Rushdie’s friend’s learn not to ask about details of his life. He can’t tell them. There is no address. There is a telephone number friends don’t give to anyone else. One calls and gets electronically diverted once or twice as the signal snakes its way to Rushdie’s destination. He watches too much television. From time to time he’s been hooked on reruns of Dynasty. He’s never truly alone. His estranged wife writes a short story about a couple on the run in Wales and repeats the resentful phrase, “The people we have to live with. . . .”

At social gatherings, Rushdie is said to avoid lights; someone could see him through the window. The man who attacked Rushdie’s Italian translator eighteen months ago first demanded the author’s address from him and then cut him up with a knife. Eight days later, a hit squad killed Rushdie’s Japanese translator in Tokyo. “Someone came behind [Professor Hitoshi] Igarashi and his throat was cut in a classic Middle Eastern fashion,” says Carmel Bedford, one of the author’s advocates.

Rushdie misses the pleasures of the unregulated life. Penny Perrick, the fiction editor of The Sunday Times, watched Rushdie arriving unannounced at a Wales literary event, brushing his hand over the hands of the people coming up to him at a book signing. He appeared to crave the random, fleeting intimacies a city affords.

In London today there are more and more signs of Rushdie. He has decided that he cannot live without a greater level of freedom and, hence, risk. “He gets out and about, secretly,” says his friend the filmmaker Hanif Kureishi. “He’s carved out a sort of life for himself,” says his friend the editor Bill Buford. Two years back, Rushdie did not go anywhere without elaborate smoke screens. Today he frequents parties where people come and go. He attends a performance of his friend Melvyn Bragg’s play forty miles south of London and some people recognize him. When Jay Mclnerney’s latest book is published in London, the police shut down all but one entrance to the Ritz Hotel so they can scrutinize everyone who, along with Rushdie, attends the book party, but otherwise the security feels lax.

“You start to think, This isn’t so bad, he has a life,” says Wall Street Journal reporter Geraldine Brooks after a meal at a restaurant near the Tower of London with Rushdie and editors of the London Times. “Then he goes to pee and there’s a gumshoe next to him.”

Rushdie’s minders are bored. They have a portable television to watch the rugby matches. At one recent party, they start washing up the dishes. In many of his forays Rushdie wears a baseball hat or a fedora. He takes a walk in London, trailed by guards. “No one recognized him,” a friend says. Often the last to arrive at a gathering, Rushdie is also often the first to leave. At those moments, his hosts glimpse an infant helplessness on his face.

“There’s terrible gloom. There are suddenly a lot of [security] people around him,” says Ronald Harwood, president of English PEN. “Two cars draw up. You don’t know which car he goes into. You don’t know where he’s going. It always makes me feel bad.”

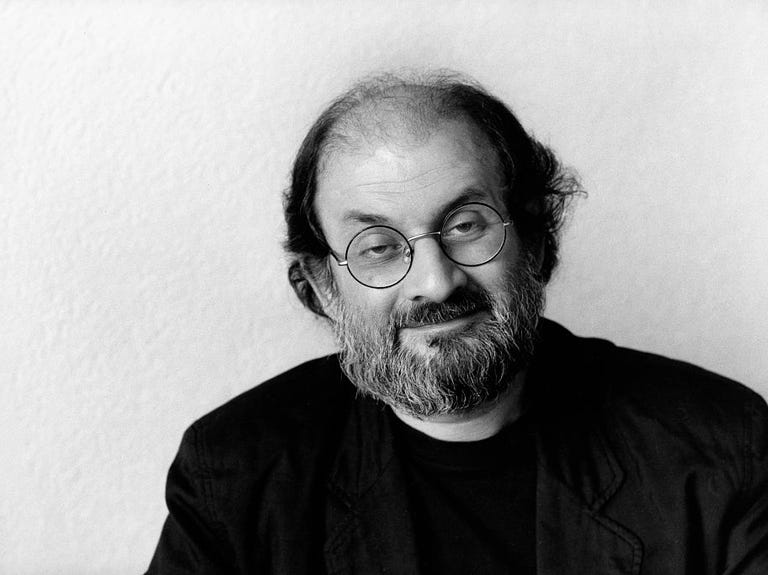

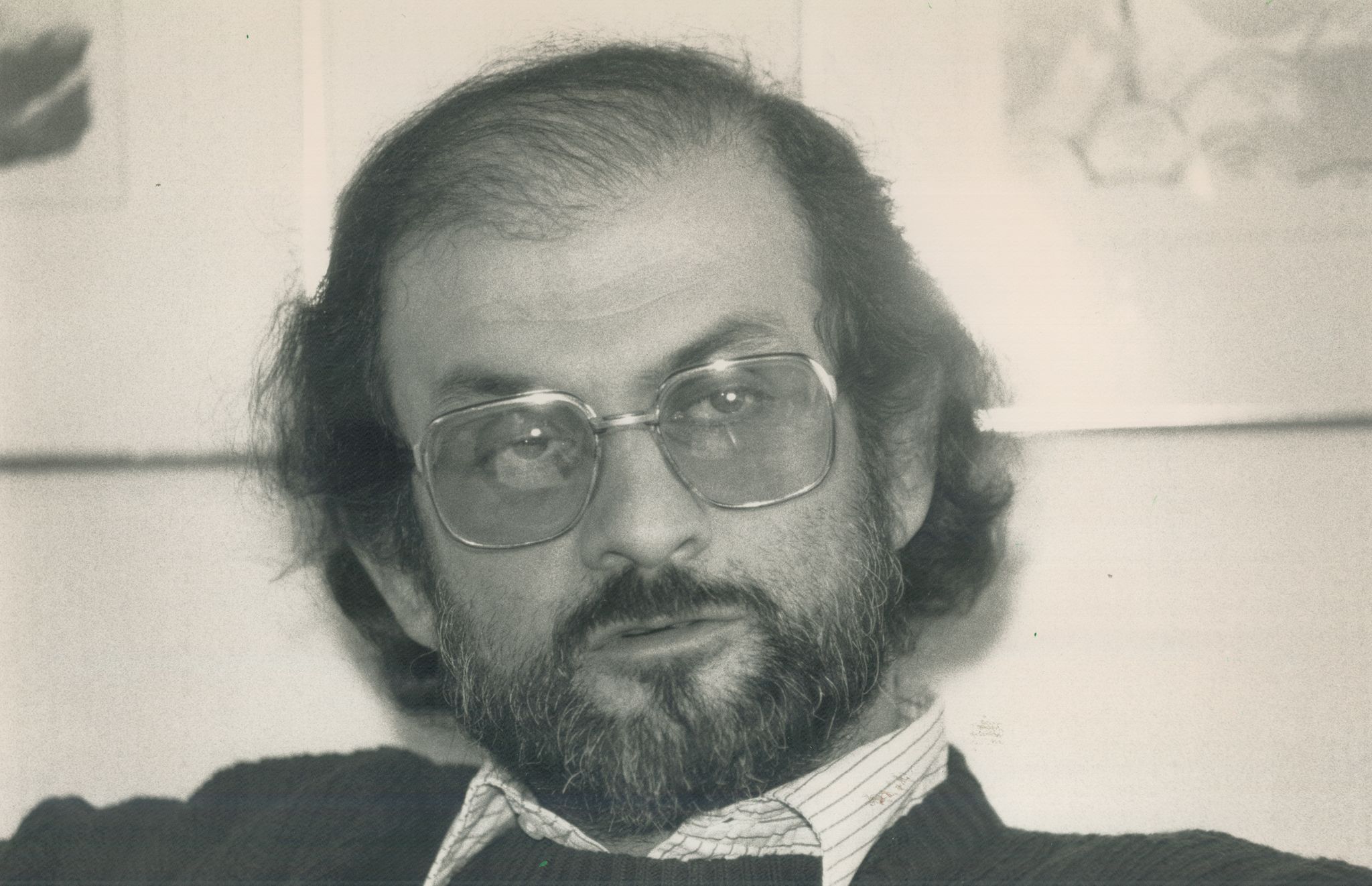

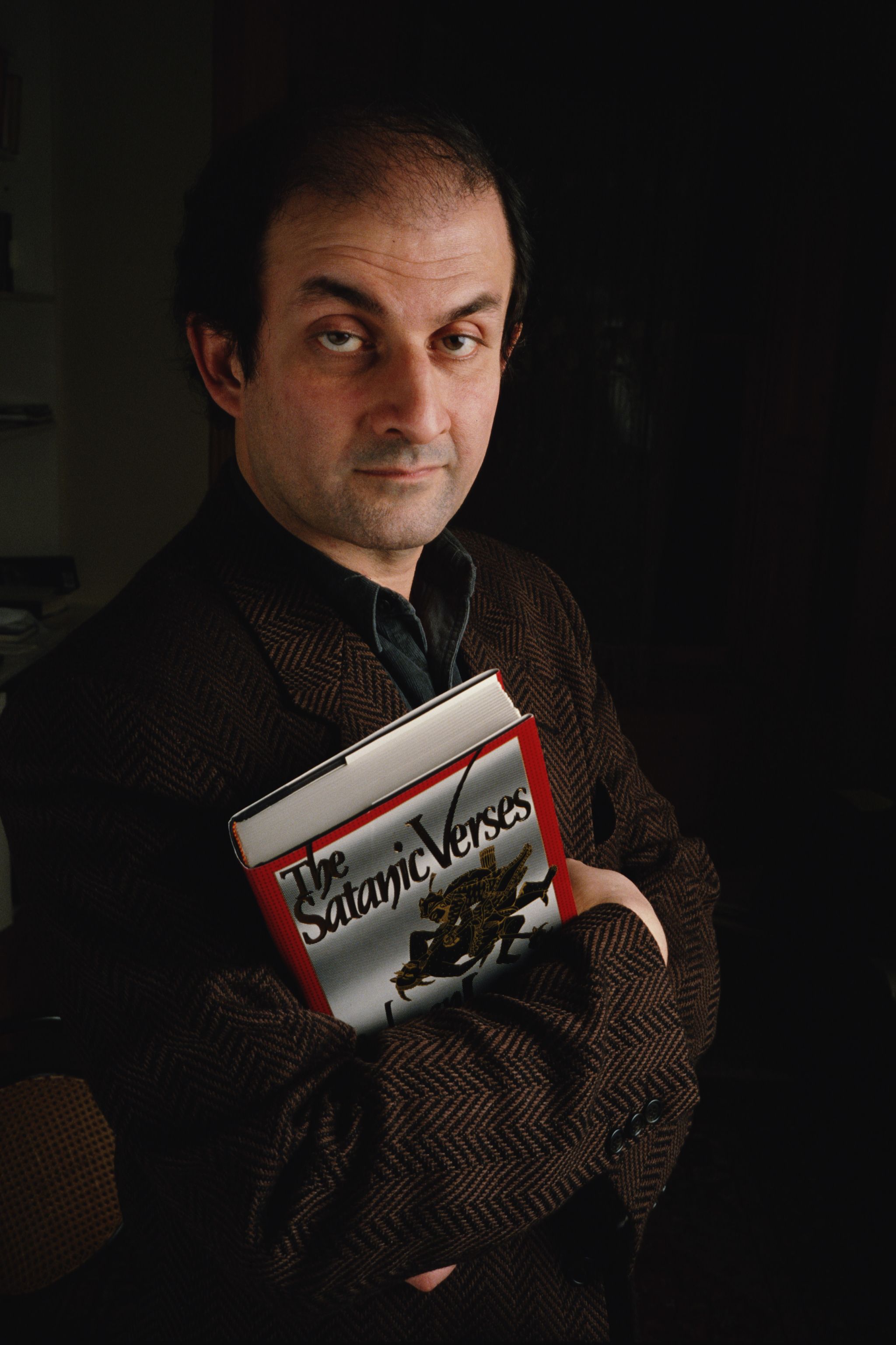

The stress has changed him. He is fatter, with a bowling-ball paunch. He developed asthma—he can’t explain why, he told Terry Gross of NPR’s Fresh Air (but among the causes of adult-onset asthma is anxiety). Friends tell the press about his tenacity, but at times he seems tormented. “It’s been . . . it’s been overwhelming, you know, to be . . . to be in a situation where, which is sort of. . . which is sort of about me. I mean, it has my name on it, but, but in a way . . . it’s completely, it’s about many other things except that, though, it remains about me, for me,” he told Melvyn Bragg on the BBC, finally blurting, “and well, I just, you know, like—any novel just better end.”

People say Rushdie is not as “instantaneous” as he used to be, that he’s mellowed, “improved.”

“There’s almost a Hollywood feeling of, yes, he’s softer and nicer,” Bragg says. “But I’ve seen Salman just as angry in the last year or so as I’ve seen him five or six years ago. I mean, really bumping-the-table angry. At a dinner for six people that I had, he was tearing the throat out of a very-very-very senior editor of an extremely important broadsheet in this country. I mean, he killed the dinner party stone-dead. There weren’t many pieces to pick up.”

The International Committee for the Defence of Salman Rushdie and his Publishers is headquartered at Article 19, a freedom-of-expression organization lodged in a four-story building in a gritty section of London’s South Bank, where, to get inside, you must be buzzed in twice. Rushdie’s chief advocates there are Carmel Bedford, a tall, solid woman with piercing gray eyes that tilt downward toward her cheekbones, and the director of Article 19, Frances D’Souza, a lively dark-haired woman dressed in a fashionable dark suit.

D’Souza depresses the plunger on a coffee maker at her desk as she laments the timidity of the West. “We are fighting state terrorism, but we cannot do that on our own,” she says. “We need people around the world to make sufficient noise that it becomes a political issue and that it becomes politically expedient for their governments to put it on the agenda, and put it high on the agenda.”

Their latest campaign is aimed at getting Rushdie to more and more Western countries as the fourth anniversary of the fatwa approaches next month, so that people will say, “Four years is enough.” In Norway last July, Rushdie met government ministers for the first time. Last September he visited Colorado. In October he went to Finland and Germany. The world seemed to be paying a little more attention. The French government even apologized for having previously denied Rushdie entry on three occasions. Bedford said that after meeting with a German government minister, Rushdie was hopeful that his case would become an “agenda point” in all talks with the Iranians. (In response, the Iranians last November increased the bounty yet again.)

The campaign’s method is to use Rushdie—the drama of Rushdie’s plight—to keep the focus on the issue: state terrorism. “We don’t then follow by telling them what he had for breakfast,” D’Souza says. Looking into Rushdie’s personal life makes his supporters uncomfortable. This discomfort most likely has to do with the fact that Rushdie the person is a very different animal from Rushdie the martyr.

“Can I just tell you one thing?” Bedford says halfway through the interview. “I’ve already had two phone calls from people saying you’re asking unwarranted questions.”

“What does that mean?”

“Perhaps you’ve asked questions that people who are supporters don’t like. They don’t want smear campaigns.”

D’Souza tries to explain. “He’s been treated very, very badly by the press here,” she says. “He is not a man about whom they’ve said, ‘Oh, he is one of ours, we’re protecting him.’ It’s an unfortunate situation, and he gets more and more belligerent.”

It’s odd to hear such things from a free-speech organization, but then Rushdie’s peril has made his supporters censorious. Associates frequently told me that they couldn’t talk about him because it was a life-and-death matter. “In view of the danger that Salman Rushdie and those around him are in, I don’t think it would be right for me to make any comment about the incident you mention,” Minette Marrin said in a note to me regarding a dinner-party outburst of Rushdie’s, which she wrote about in the Sunday Telegraph before the fatwa.

Marrin’s logic, which others echo, might be thought of as a choice between political correctness and his death: If one chips away at Rushdie’s image, one chips away his political support, thereby casting him into the abyss. After all, the British government has waffled on providing protection. Meanwhile, the right-wing papers have made Rushdie into a sort of devil who is expensive to keep. After one of Rushdie’s BBC interviews, the Daily Mail listed “eight crucial questions they failed to ask.” Number 3 was, “Do you believe the novel revealing your animosity to the religion of your birth outweighs the deaths that have resulted?”

Julian Barnes, the novelist and a Rushdie friend, explains: “The British government is committed to the extent of wanting to avoid the embarrassment of having one of its subjects assassinated by an agent of a foreign power. That’s the extent of their commitment. But there are just not enough votes in standing up for Salman. Both parties are scared of antagonizing the subcontinental-origin ethnic population. It’s a vote-loser. It’s not a vote-winner.”

Other allies argue that for political purposes, Rushdie can’t be seen having a good time. When reports about him, say, singing a Rolling Stones song karaoke-style at a wedding appear in print, there is talk of betrayals. Writer Michael Herr says, “Among the things that Salman learned is who his friends are, who he could trust, who among his friends were promiscuous with information.”

And yet Rushdie is a legendary bon vivant. And his situation has produced strangely layered arrangements of social power and powerlessness that even his fiction cannot match. One woman in the London literary scene said to me waspishly: “The thing that made me go eek-eekis the way the women were being laid on. It was, ‘Oh, be nice to Salman,’ or, ‘Salman would like your telephone number.’ I had girlfriends who were seated next to him at dinner, and you had the feeling Salman had said, ‘Could you invite X, we’ve never met.’ It felt like a form of pandering, a high-class pimping service. There was an uncomfortable closeness to it all. I mean, I don’t care if a man had a noose around his neck....”

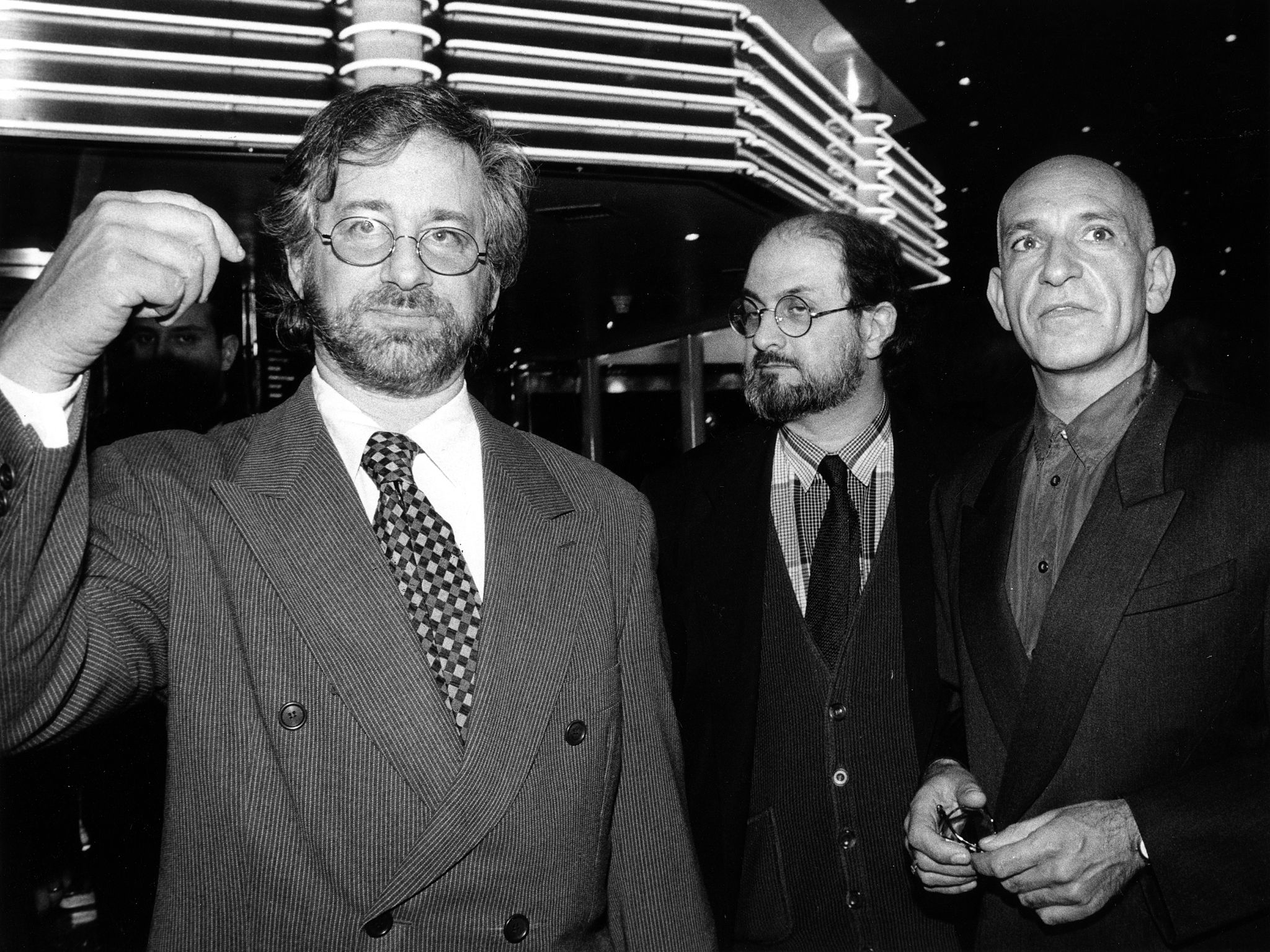

Rushdie is almost always the focus of attention and seems to revel in it. “He never thought there was anything out of proportion in the coverage of him,” one friend says archly. Famous writers—from Gass to Grass, and Styron too—travel across continents to show solidarity with him at his sudden appearances. Plainly, he gets catered to. Stories of his movements are full of such devices as British army planes, helicopters, boats in the Channel near Elsinor in Denmark, and a Scandinavian island where he meets his son for a fishing vacation. Katharine Graham has him to tea with Bob Woodward. On one day’s notice, a half-dozen U. S. senators lunch with him, against the wishes of the Bush administration, at the center table in the Senate dining room.

At London dinner parties there are stagy melodramas as guests await the arrival of the last diner, whose place may be indicated by a cute card saying A. N. OTHER. No one is supposed to know who it is but, writers being writers, everyone does. “I’ve heard so many tales of the empty chair at the dinner party, and at the last moment Salman slips into it, and there’s a sigh,” John le Carré says with mock breathlessness. “The pleasures of being Salman, the privileges of being Salman, are there, and in the circumstances, how can one possibly grudge him that?”

In some of these tales, Rushdie appears grandiose, childish, a kind of king of literature testing the devotion of his subjects. When gossip about him appears in the press, Rushdie is said to grow enraged. “I see lies about myself in the newspaper every day for three years,” he said bitterly to BBC radio. There’s a dead zone of speech around Rushdie, a no-man’s-land burned to the ground and cratered by his paranoia. (Rushdie declined to be interviewed.)

At the end of my interview with the author Fay Weldon, she expresses concern that carelessness with her comments could get her into trouble with Rushdie. “This whole thing has been great training in not saying inadvertently what one would not wish to have said,” she says quietly. “One learns. One learns.”

In this climate, at least one member of the Rushdie camp has been punished for speaking out. In 1991 Rushdie’s second wife, Marianne Wiggins, with whom he spent the first fugitive year of the fatwa and from whom he is now getting divorced, broke free from what she called her straitjacket of devotion. She spoke to a London Sunday Times reporter and described Rushdie’s self-obsession.

“All of us who love him, who were devoted to him, who were friends of his, wish that the man had been as great as the event,” Wiggins was quoted as saying. “That’s the secret everyone is trying to keep hidden. He is not. He’s not the bravest man in the world but will do anything to save his life.”

Wiggins’s comments had a bracing American openness, but in the literary community they were seen as a betrayal. “It completely destroyed her in this country. No one would return her calls,” says one English observer. Wiggins was promptly fired by the powerful literary agency of Wylie, Aitken & Stone, which represents Rushdie as well. “New York felt it was time to bring the relationship to an end, and I agreed,” Gillon Aitken says in London. “We didn’t feel [her statement] was particularly helpful. Marianne had made her position clear. We couldn’t really represent them both after that.” Later, speaking of Wiggins on BBC radio’s Woman’s Hour, Rushdie said, “I’m afraid that Marianne did tend to get what benefit she could out of the connection with me, and that was sad.”

Rushdie may have more to fear from his own statements. Even in short visits he manages to alienate people who would otherwise support him. When he surfaced in Washington last March, he announced the paperback publication of The Satanic Verses in front of a freedom-of-expression conference, attended by many persecuted writers, at Gannett’s Freedom Forum. He did not acknowledge the case of any of his fellow writers there, and many of them left shaking with anger.

Melor Sturua, a former Izvestia editor, says, “The main difference between those around him and him—these people, they are real freedom fighters. They were tortured by Pinochet; in Russia; in El Salvador. He begins from the first word, advertising his book, without even saying one word, I am so happy to meet my fellows who are fighting for freedom of expression. He wasn’t looking at us even. He was so immodest that he compared himself with Galileo, with Socrates, with Jesus Christ.”

Adds Rehana Rossouw, a South African journalist who has spent months in prison without trial because of her statements: “I was so impressed at first, but then he upset me terribly. I put my camera away. He was so very arrogant. He didn’t mention at all that what had happened to him had happened to others before. Everything he said was self-promotion.”

Of course, it would be best for Rushdie if people came away from his dramatic descents into the world wearing buttons saying I AM SALMAN RUSHDIE, as they did in Colorado recently. When they wear the buttons, they are making a connection between his case and a freedom they usually take for granted. Because of Rushdie’s personality, this connection happens all too rarely. But as Tom Blanton, director of the National Security Archive and a Washington conference organizer, argues: “The people who are hardest to defend are always the ones most worth defending.”

That’s the problem with the principle of free speech. It would be so easy to fight the good fight if John Updike with his easy smile were in Rushdie’s place. But no, so often it is provocative, unpleasant people. Rushdie the man shouldn’t affect Rushdie the cause. And yet somehow he does, even to his supporters.

When I tell Siobhan Dowd, who works at PEN in New York, that Rehana Rossouw found Rushdie to be arrogant, she gets an edge in her voice. “I don’t think it’s doing the cause of free speech any good to use an adjective like that,” she says. But what if it happens to be true? Will we love free speech any less?

Even in the respectable English papers today you will see the author labeled Old Rugbeian Salman Rushdie. There is a deadly British irony in that phrase, a commentary on the fact that an immigrant, and one known to be ill-mannered at that, has penetrated the country’s most elite institutions, in this case Rugby, a venerated public school. The same apprehension is detectable when the Daily Express remarks that Rushdie’s first marriage was to a well-born woman, the “tall English-rose type.”

This is the most accessible layer of Rushdie’s personality, the immigrant. When he arrived at Rugby from India at age thirteen, “cruel tricks were played on him,” says Michael Herr. “In English society, Salman is a black man. This is his subject, the endless outsider. He’s used it to make art with. But it doesn’t take away the pain and self-hatred.”

Some Muslim critics hint that Rushdie has been deracinated. Ahmed Salman Rushdie (that is how his name is listed in Her Majesty’s Land Registry) was born in Bombay in 1947 to a wealthy Muslim family. His father was an alcoholic and “a great anglophile,” Rushdie has said. The son was sent to a British-style school in Bombay where he learned to say the Lord’s Prayer. He memorized the names of English football and cricket teams.

Rushdie’s incredible sensitivity to criticism also has a racial dimension. I heard one acquaintance describe Rushdie’s diction as “high-class chee-chee,” a derogatory term for the Anglo-Indian’s inflected efforts to speak the King’s English. There is talk about his odd looks too, his hooded eyes and unruly beard and beaky nose. At a party last year the writer Gordon Burn, whose novel Alma Cogan Rushdie had given a mixed review, mocked Rushdie by calling him “Simon,” thus anglicizing his name. It hit a nerve.

“Okay. I didn’t like your fucking book,” Rushdie is said to have retorted. “Why make me bleed to death? Why not kill me now!” A guard came flying into the room, hand on his gun.

But ethnicity has been Rushdie’s gift too. In a society that traditionally prides itself on reserve, many in his circle found his dervishy thereness liberating. His friend Liz Calder uses the term “un-British” to describe his style. I asked her to elaborate. “Confrontational. Excitable. Passionate. Outspoken,” she says. “You know, like many brilliant people, his company is absolutely exhilarating. He is one of the most amusing conversationalists, mimics, and actors. He is a very, very funny man.”

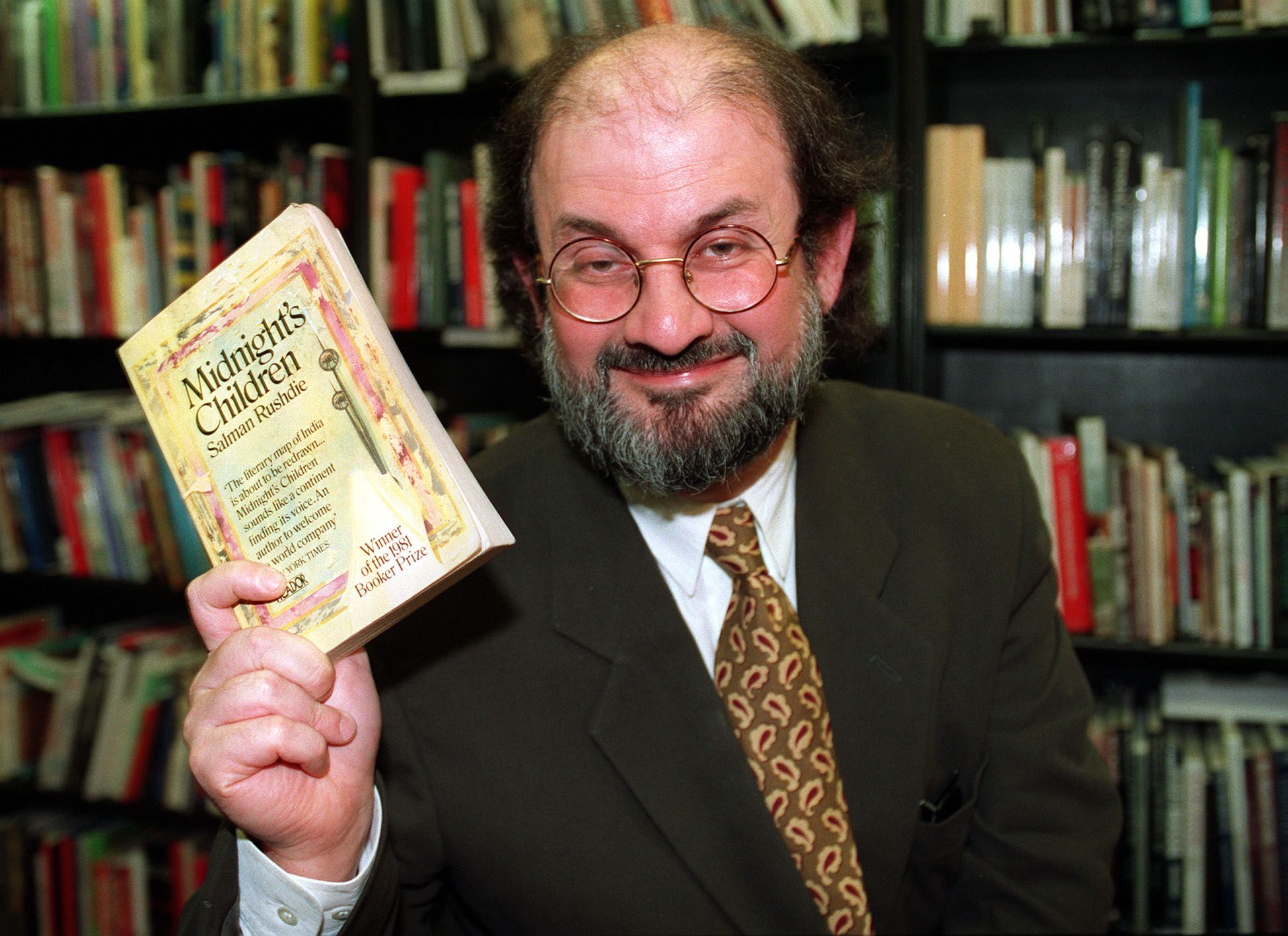

Calder discovered Rushdie. She was a lodger in his London home when he was still working in advertising, and she nurtured him through the failure in 1975 of his Western-oriented first book. Four years later, Rushdie made a daring leap: He began using native material. Midnight’s Children was a spiraling, untidy magical-realist novel about India and Pakistan and postcolonial Britain. That October, in the locusting rite of backstabbing and coziness that surrounds the awarding of the Booker Prize, D. M. Thomas’s The White Hotel was widely thought to be the favorite. But true insiders understood that Rushdie’s big, messy (and leftish) book was the new great thing. Here, at last, England had Division I intercontinental talent. He won, and his reputation was established.

Rushdie was hugely proud of his Booker. He clucked over it in his own writings, and in 1983, when his next book, Shame, failed to win the prize, Rushdie stood at his table at the formal dinner and yelled at the judges. Wine spilled into his wife’s lap. For years afterward, he hardly spoke to Fay Weldon, who chaired the committee.

The papers referred to that outburst as a tantrum. Reading the English clippings on Rushdie, one is struck by how social his identity is, how public his battles have been. His fiction had a public element, too. It dealt with identifiable figures, to the point where Indira Gandhi took him to court over his suggestion in Midnight’s Children that she had brought about her own husband’s death.

The author is a provocateur, and like all provocateurs, he both seeks attention and thinks he’s being clever when he’s being mean. “I discovered to my horror that all the political figures most featured in my writing—Mrs. G., Sanjay Gandhi, Bhutto, Zia—have come to sticky ends,” he told The Independent in 1988. He continued in a way he seemed to think was witty: “It’s the grand slam, really. This is a service I can perform, perhaps. A sort of literary contract.”

The unfortunate irony of this statement came around all too quickly. Six months later, on Valentine’s Day 1989, a reporter for BBC radio called Rushdie at his stone house in a fashionable section of North London to inform him that the ayatollah had issued a death sentence. Rushdie promptly closed the shutters. That afternoon he went out to a memorial service for Bruce Chatwin, after which he was hustled away by police. The writing world, by and large, was strangely unmoved. A literary agent says people joked of the fatwa. A New York editor who had worked with Rushdie said, “I can think of much better reasons for killing Salman Rushdie.”

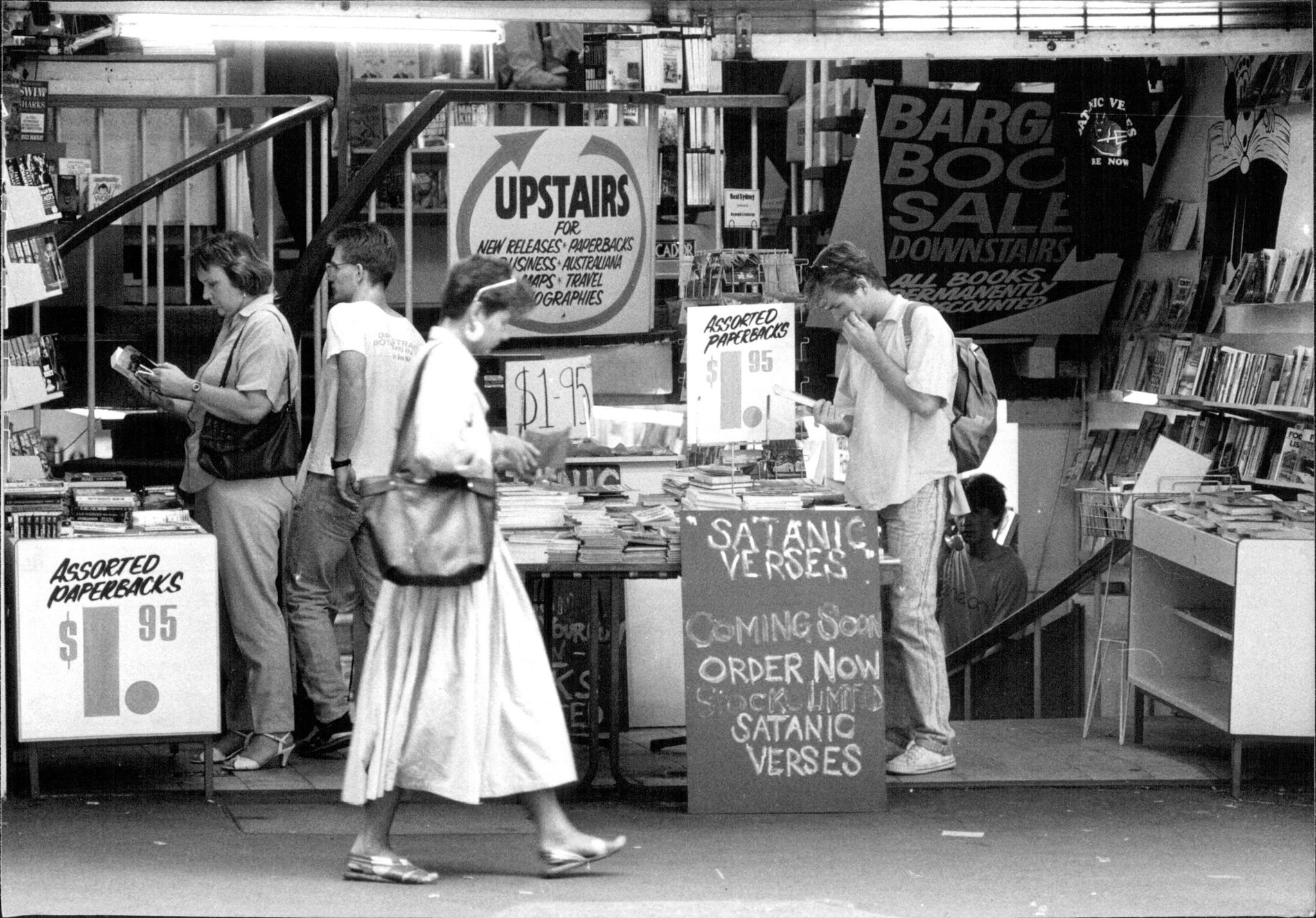

Last March Salman Rushdie came to Washington under the greatest secrecy with his new girlfriend, an English woman described as being at least ten years younger than he is, with a crystalline complexion and long straight hair, carrying what looked to be a kilim bag. He’d come to announce the paperback publication of The Satanic Verses, two years late. He gave out copies to U. S. senators and produced the book at a press conference. “It’s an emotional moment. But there it is,” he said, gazing softly at the book.

Rushdie became insistent when he said he wanted to take the book back from those who hate it. “A lie” has gone out to the world about his book. He has letters from Muslims who love The Satanic Verses. He wasn’t going to answer “anger with anger.” Blasphemy was the very charge used against Socrates, Jesus Christ, and Galileo to put down their truths. “The power to describe it has fallen into the hands of its enemies,” he said. “They are wrong. The kind of fictitious, demonized Satanic Verses that exists in the popular mind is no more the book that I wrote than I am the fictitious, demonized person whose effigy is burned in the public square.”

There is much to be said for Rushdie’s view. The book brims with affectionate, comic portraits and moments of wonderful storytelling. But the trouble with Rushdie’s position is that he does not acknowledge what is plain to others—that the book has a provocative, angry component as well (“deliberately transgressive,” in the words of the Palestinian academic Edward W. Said). Even the title is a taunt, referring to the most shameful episode in Muhammad’s life. While it is true that some Muslims, often highly privileged ones, have applauded the satire, theirs is a fringe response; broadly speaking, Muslims of all sorts have said that they feel insulted by the book’s portrayal of Muhammad, referred to in the book by the Middle English mongrelization Mahound.

“Muslims actually love the Prophet and his households more than they love their own souls and their own households,” says Hesham El-Essawy, who is associated with London’s Central Mosque. “In other words, insult a Muslim’s mother, he might turn the other way. But insult the Prophet, he will go mad.”

Of course, insulting religion is something artists do in the West. Ridicule can be liberating (and some scholars have argued that Rushdie’s satire is in an Islamic tradition). Artists plumb their unconscious for their work. If there’s anger there, so be it. Words spoken in anger are often true.

But these principles are not popular. And to the extent that the affair has called on Westerners to explain and justify them, the argument has been confused at times by Rushdie’s failure to take full responsibility for his work. It is as if he had written The Wind in the Willows and were now shocked, shocked, by the response. He argues, for instance, that Muslim scholars have concluded that “there’s nothing here, this is not offensive.” As one such scholar points out—Abdulaziz Sachedina, a Western-educated professor of religion at the University of Virginia—this claim “does injustice to Muslim sentiments.”

Last March, Rushdie said that the controversial sections about the Prophet—narrated during the feverish dreams of an actor who’s slowly cracking up—“are heavily ironicized, heavily distanced from any authorial position.” That sounds very postmodern. But it’s also slippery. Before the fatwa, Rushdie struck a much more earnest tone: “In this dream sequence I have tried to offer my view of the phenomenon of revelation and the birth of a great world religion. . . .”

The ways in which the book was sure to offend have caused many to wonder, What did Rushdie expect?

“He is well versed in Islamic ideas: He knew what he was doing and could foresee the consequences,” the critic Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote in 1989 in The Independent Magazine. “If an expert entomologist deliberately pokes a stick into a hornets’ nest, he has only himself to blame for the result.”

There can be little doubt that Rushdie knew he was treading on sacred ground. He had studied Islamic history and had run afoul of Muslim sensitivities during a stint in Pakistan (the word pork was removed from a play he wrote). His writings suggest that he was aware of how touchy fundamentalists are to works that even mention the Prophet. As Viking Penguin was preparing The Satanic Verses for publication in 1988, a Penguin editorial consultant in India wrote to the London offices to say that the book was “lethal.”

Some writers, even a couple of Rushdie’s allies speaking privately, notch Trevor-Roper’s argument up a little to say they believe Rushdie sought an explosion as a way of getting more attention. Rushdie has said such arguments blame the victim much as Jodie Foster’s character in The Accused was unfairly blamed for bringing on her rape. But there is evidence that, short of the fatwa, and perhaps unconsciously, Rushdie welcomed some type of confrontation over The Satanic Verses. The theory works like this:

Thanks to the ferocious efforts of Rushdie’s agent, Andrew Wylie, Viking Penguin paid an $850,000 advance that staggered the publishing world. But on publication in September 1988, the book got disappointing reviews, though it did make the best-seller list. After the book lost out on the Booker and another big prize, Rushdie went into a public sulk. He said that England had driven away other great talents. Now he was thinking of moving to New York.

The attention from the Muslim world seemed to fulfill Rushdie’s sense of his own importance. When the Indian government banned the book in October 1988, Rushdie fairly taunted Rajiv Gandhi. His writings addressed to the then-prime minister are puffed up and nutty. “Mr. Gandhi, has it struck you that I may be your posterity?” he wrote. “Are you certain that the cultural history of India will deal kindly with the enemies of The Satanic Verses? You own the present, Mr. Gandhi, but the centuries belong to art.” Then in January 1989, Muslims in Bradford, England, burned the book, and in February, riots in Pakistan and India over The Satanic Verses left six people dead. Rushdie responded with a kind of jauntiness. At the BBC on February 14, the day after the rioting ended, he joked off air about going on holiday in an MFZ, or “Muslim-free zone,” and said, on air, “Frankly, I wish I had written a more critical book.” Even friends of Rushdie’s speak of the comments as inappropriate—“extremely self-centered and lacking in empathy,” as one puts it.

It was the riots that apparently got the ayatollah’s attention; and Salman Rushdie had found an enemy who was a lot angrier than he is.

“There’s a Jewish saying: Be careful of what you want, you may get it,” says the writer A. Alvarez, gripping a pipe in his teeth and throwing himself back in the rather eccentric rocking chair he uses to save his back. “Rushdie wanted to be the most famous writer in the world, and now he is and it’s not what he expected.”

Hesham El-Essawy is a forty-six-year-old Egyptian-born Muslim who has struggled for years to convince the world that Islam is not intolerant. He is a smooth-skinned man with a calm, trusting gaze, and he has done well. He is a dentist, with offices in a fashionable section of London near Regent’s Park. A stack of his cards is bedded in lavender seeds in a silver dish.

I went to El-Essawy’s office at the end of the day and stayed late listening to him. He played a key role in the Rushdie case. He reached out to the author in 1990 after he heard him mention God in an interview and encouraged him to embrace Islam. El-Essawy hoped to demonstrate to the world that Islam is, above all, forgiving: A man can wipe his slate clean. He had a plan, involving Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, to lift the fatwa. Rushdie went along. In late summer Rushdie privately spoke the Muslim creed: There is no God but God and Muhammad is the messenger of God. El-Essawy was convinced of the writer’s sincerity. He told me about a day he watched Rushdie agonize over what he hints was a threat to the life of the author’s son, Zafar.

“I must leave it in God’s hands,” Rushdie said with deep grace.

Rushdie’s public Christmas 1990 statement that he had become a Muslim stunned his friends. There had been a plan underfoot for him to move to the United States. Now he was turning east. Some free-speechers abandoned the cause. “There was a collective wheeze as all the pressure went out of the [pro-Rushdie] enterprise,” says one friend.

Perhaps most damaging was Rushdie’s concession in the Christmas statement to suspend publication of the paperback of the book. The statement undercut the position he had taken on the matter, which was one of defiance. For some time Rushdie had been lashing Viking Penguin for refusing to come out with a paperback. His righteousness on this point was, even in the view of some free-speechers, problematic. Viking Penguin had kept the hardback widely available. Moreover, the publisher was specifically targeted by the fatwa, too. Its employees felt great fear and didn’t have the government protection Rushdie was afforded. When this point was raised with Rushdie, he was angered. “There is only one person here who is in any danger of dying.” (Following the attack on his translators the next year, however, Rushdie made a more generous statement, calling for action “before any more innocent people die.”)

Now in his Christmas statement, Rushdie suddenly pronounced, “The binding of a book is not a moral principle.” And privately, he was preparing “a message from the author” to be affixed to all as-yet-unsold hardback copies of The Satanic Verses. El-Essawy pulled a fax of this statement from his desk, signed by Rushdie, to show me. “I do not agree with any of the characters in this book who, by their statements or attitudes, insult the Prophet or cast aspersions upon his character, or upon the authenticity of the Holy Koran, or who reject the divinity of Allah. . . .”

Some said that Rushdie wanted to save his skin. If so, it put his supporters in an odd position. They had said that they were willing to die for Rushdie’s right to speak. Now it appeared that the author himself was not willing to die. The New Republic compared Rushdie’s statement to “one of those chilling and transparent exercises in ‘self-criticism’” under communist regimes.

Muslims tend to see Rushdie as a more complex figure, someone with both love and hate for his Eastern origins. “He is so keen on being accepted,” says El-Essawy. “But I was talking to him once and he got angry, and he spoke just like any angry Indian friend of mine would speak. I said, ‘You are an Indian after all.’ He said, ‘That’s right. I got nothing from this country. Other than the language.’”

Unfortunately the conversion did nothing to move the Iranians, and within months Rushdie began backing away, calling his embrace of Islam “a mistake.” When he popped up at Columbia University in New York in December 1991, he devoted much of his speech to a tortuous explanation of why he had converted. He had hoped to become a secular Muslim in the same way that there are secular Jews. But his dreams of modernizing Islam ran up against a stifling culture that has “failed to create a free society anywhere on earth.”

“Suddenly I was, metaphorically, among people whose social attitudes I had fought all my life,” he said. “Had I truly fallen in among such people?” For instance, the Muslim attitude toward women was shocking. “One Islamicist boasted to me that his wife would cut his toenails while he made telephone calls and suggested I should find such a spouse,” Rushdie said.

El-Essawy saw that speech. He recognized himself in the anecdote. His English wife is a chiropodist, a fact he says Rushdie was aware of on a day the author had telephoned him and El-Essawy had cried out in pain.

“Rushdie said, ‘What are you screaming about?’ I said, ‘My wife just chose this minute to attack my toenails.’ So he laughed. He said, ‘You lucky so-and-so. You have a wife who trims your toenails? I had two of them, and none of them trimmed my toenails.’ I said, ‘Well, perhaps you didn’t have a wife who can.’”

El-Essawy’s broad face darkens. He folds his fingers solemnly across his white dentist’s jacket. “When I saw that, it made me angry. He knew I wasn’t boasting, because he heard me scream. . . .”

It was 9:00 P.M. El-Essawy’s wife called to find out where he was, and he made kissing sounds into the receiver, telling her he’d be right along. He walked me to the door.

“You asked me what else do I like about him—he has a childlike quality you can like,” he said. “But you see, for a man who is so intelligent, he is the dumbest man I ever met.”

At the Columbia speech, Rushdie had called for publication of the paperback, after all, and three months later in Washington he unveiled the book. It was published by an anonymous consortium whose president, according to corporate records, is Rushdie’s agent, Andrew Wylie. For Western liberals this was an important moment—the issuing of a book that for some time a publisher, intimidated by fundamentalists, had refused to print.

Even so, there were sour notes. The publishers were not willing to put their names on the book (the only address in the book, given for the consortium, is actually for a subsidiary of Simon & Schuster that acts only as an incorporator in Delaware; and S & S says it has nothing to do with the publication). A plan to give some proceeds from the publication to a free-expression entity died—in part due to the Association of American Publishers’ failure to back the book, and in part too, says free-speech advocate and Harper’s publisher John R. (Rick) MacArthur, because of Wylie’s lack of interest (Wylie declined to be interviewed). The night the book was published, Nation editor Victor Navasky asked Rushdie about such a charitable effort. Navasky suggested that the next incarnation of the book, a mass-market paperback, could have the publisher’s share of profits dedicated to a publicly minded First Amendment-oriented entity.

Rushdie nodded rapidly and dabbed at his beard. Then, smiling, he said, “I think the correct answer to that is, Talk to my agent.”

The next day the White House echoed that cynical sentiment in a grotesque fashion. “There’s no reason for any special relationship with Rushdie,” said White House spokesman Marlin Fitzwater. “I mean, he’s an author, he’s here, he’s doing interviews and book tours. . . .”

As revealing as the comment was of the Bush administration’s stance on human rights, it demonstrated Rushdie’s problem: In a defining moment, he never seems heroic. Heroes are flat characters, or they become them. They transcend their self-interest so completely that they will sacrifice everything for an idea. Peggy Say, the sister of Terry Anderson—the AP reporter and former hostage—became so committed to the cause of human rights that nearing the end of the ordeal, when it was suggested that money be offered for his release, she went on television in Damascus and said, “If I had a million dollars in my hands, I wouldn’t give you bastards a dime.” “Death is a onetime event,” she says. People with such conviction sometimes change the world.

But Salman Rushdie is an artist who lives in his own very complicated cosmos. His sense of commitment does not seem to go much beyond himself. For those who wanted a hero, Rushdie’s recent change of publishers has also been a source of dismay. The story began making the rounds in England last summer, in a whispered fashion. It involved Rushdie’s old associate Bill Buford.

Buford is a thirty-eight-year-old expatriate American who during the Eighties made the quarterly Granta into the seedbed of an exciting, raw fiction—dirty realism, it was called. Buford is a highly likable editor with an entrepreneurial side. He has blocky, Hemingwayesque good looks and dresses like a Bob Hoskins character who’s made it.

In 1989 Buford began publishing Granta Books, with Viking Penguin as his distributor, and in 1990 he began publishing Rushdie. He brought out two books: a magically inventive children’s book called Haroun and the Sea of Stories, which some consider Rushdie’s best work, and a collection of essays called Imaginary Homelands. According to several sources, Knopf director Sonny Mehta, an old friend of Rushdie’s who was born in India, had the books under contract, but the deal collapsed because Random House president Alberto Vitale grew fearful of the risks in publishing Haroun barely a year after the fatwa. By one account, Vitale wanted the author to guarantee the publisher’s costs if it should require extra security. In another source’s telling, Mehta was under great pressure to assure company lawyers that there was no risk in the book, and so he asked Rushdie to change its setting from India to Mongolia, “promising him that there would be bodies on the streets of India if he didn’t.” Rushdie, who was reportedly infuriated, withdrew the books. (Through a spokesman, Vitale and Mehta declined to respond to these assertions.) The books went to Granta.

In a brief, cool meeting I had with him, Buford said, “Our view was to publish it as openly, as energetically, as positively as possible to dispel the fear.” The “spirit of celebration” would make people understand that the only thing to fear was the fear itself. Asked if he ever worried for his life, Buford shrugged it off. “There were no threats.” All the same, friends of Buford told me that he privately feared the consequences of his bravery. He and his wife-to-be never left their house in Cambridge unattended for fear of a firebomb or a burglary.

Buford also became Rushdie’s protector. He dealt with the press and handled crucial aspects of Rushdie’s security. “Bill has been Rushdie’s link to the outside world for three or four years,” says one friend. “He’s done huge amounts to make Rushdie’s life better for him.”

Of course, Buford published the books not just as a loyal friend but as an entrepreneur. He made what some say is a losing investment with the expectation that Rushdie’s next big novel would come to him. The book’s working title is The Moor’s Last Sigh, and it is said to include, as its historical component, a treatment of the Moorish civilization of Andalusia (now part of Spain) that ended in the late fifteenth century but represented, for a short time anyway, a harmonious mingling of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic heritages.

Things began to look bad for Buford in January 1992 when Penguin, Buford’s publishing partner, said finally it would not publish the paperback of The Satanic Verses. Rushdie is reported to have been angry with Penguin’s decision and put pressure on Buford to end his distribution relationship with the house. To break a successful business relationship for one author—that was absurd.

Meanwhile, The Moor’s Last Sigh slipped into the wind. Andrew Wylie was talking with Random House. But Rushdie was still angry with Random House’s Sonny Mehta over the Haroun incident. So Wylie reportedly sold worldwide English-language rights to the book to Erroll McDonald at Pantheon, an imprint Mehta oversees. The book was never even offered to Buford.

“I wasn’t happy about it,” Buford told me, but he declined to comment further. Friends say that he was hurt—“Be nice to Bill, his girlfriend’s left him” was one snide rendering of his abandonment by Rushdie. Moreover, Rushdie reportedly didn’t tell Buford in a straightforward manner. “And Bill literally put his life on the line for him,” one writer told me.

Of course, Rushdie was being a sharp businessman. Buford apparently thought the two shared a real friendship. He had even gone so far as to make Rushdie best man at his 1991 wedding, a glamorous affair on the banks of the Cam in Cambridge, attended by such lights as Mehta, Julian Barnes, and Germaine Greer. Rushdie appeared unannounced, surrounded by a half-dozen bodyguards. His highly wrought toast that day became legendary. Witnesses say it went on for half an hour and ran down Buford as underhanded, without the customary leavening of affection. The speech ended on a jaw-dropping note, saying the chances of finding happiness in marriage were similar to the chance that a man jumping from an airplane at four thousand feet will land on a bale of hay.

One guest, the American filmmaker Ric Burns, says the effect was poignant. “It was an unusual speech for a best man to deliver, a pillar of fire rather than epithalamium. But one would think that whatever was bleak about Salman’s performance stemmed from his isolation and not from any ill will toward Bill.”

For all the torments Buford experienced, his courage has allowed others to proceed without fear. Haroun, Imaginary Homelands, and the paperback version of The Satanic Verses have come out without any trouble. The Moor’s Last Sigh is not due to be published until 1994. By then the risks will be “wearable,” says one British publisher.

“Is that a courageous act on the part of a dwarf?” Roger Straus of Farrar, Straus & Giroux asks rhetorically of The Moor’s Last Sigh. “No one is worried about that book.”

I asked him if by dwarf he meant S. I. Newhouse Jr., who owns Random House.

“Did I say that?” he said. “Someone else must have said that.”

The last night I was in England last fall, I went to dinner with a writer friend who offered a terrible view of Salman Rushdie’s fate. In the eyes of many British people, she said, “he has already been claimed.” She drew on a cultural understanding that goes back to the Crusades, when Christians and Muslims battled for souls. To claim a soul often meant to kill the person. My friend was saying that in the hearts of his countrymen, Rushdie, a foreigner by birth, is now answered for.

Experts on the politics of the situation don’t sound an altogether more optimistic note—that Rushdie’s survival will depend on how careful he is. The European countries do business with Iran even while Iran pursues a policy of extraterritorial murder. Lately the government has been linked with the killing of three Kurds in Berlin. The United States has little at all to do with Iran, but even if it restored relations, how much of a priority is Rushdie? Human rights lose out to economic rights all the time, in China, in Turkey, in Indonesia.

“There is no question in my mind that if there was the political will this could be solved instantly, less than five minutes,” Frances D’Souza says briskly. But the foreign-relations experts I spoke to said that even if the West demonstrated resolve on the issue, the fatwa is too important to Iranian self-definition to dissolve.

“A dominant theme of the [Iranian] revolution is achieving autonomy against the background of perceived domination by the West,” says R. K. Ramazani, an Iranian-American at the University of Virginia. “Pressure tactics [on the fatwa] would be seen as arrogant and bullying.”

A staffer for Democrats on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee pointed out that the fatwa costs Iran nothing. Even if the moderate Rafsanjani regime privately wants to yield the point, lifting the fatwa would instantly turn the center to the hard-liners. “Isolating Iran may deter further acts of terrorism,” the staffer said. “What it is hard to see that it would do is lift the fatwa.”

With this grim backdrop, the international campaign for Rushdie at times resembles a theater piece, a traveling show that has less to do with winning hearts and minds than with the players’ sense of their own importance.

I talked to Scott Armstrong, the Iran-contra maven and coauthor of The Brethren, who was Rushdie’s host on the Washington trip last March. The visit was thrilling, like a spy story. They switched cars in underground garages, cleared and secured bathrooms in the Capitol, even thought of putting steel shutters on the Gannett Building to keep out missiles. Private security cost Gannett $70,000, he says.

“The biggest fear,” says Armstrong, “was that something would leak out, someone would try and fly a plane in the window, or that there would be an attempt to blow up the building, from a bazooka from Roosevelt Island to a shoulder-launched missile. There’s a tremendous amount of open space where someone could stop a car, get out, and in a matter of sixty or seventy seconds line up a shoulder-launched . . . get the cross hairs on that window, and fly something in the window.”

In the midst of the hysteria, Armstrong says he spoke with the FBI and learned that the counterterrorism unit was wiretapping Muslims.

“There were several hundred people who listen to conversations,” Armstrong says. “My guess is that every Farsi speaker who worked for the federal government in any agency was called into service during the relatively short period of time that he was here to listen for indications of activity.” (For its part, the FBI says that it cannot discuss sources and methods.)

“Was there any real threat to Rushdie?”

“No threat occurred because their timing was so slow. They were looking for him, but there was no specific attempt to do anything against him because they were unable to find him.”

“Who are they?”

“I’d like to go off the record.”

Literary types in Britain get a thrill similar to Armstrong’s. They feel themselves to be at the barricades of a cultural war. They are reminded that words matter. Islam has replaced communism in their minds as the great enemy of free thought. Salman Rushdie is their Berlin Wall.

Of course, Salman Rushdie gets something out of this, too. Perhaps the most surprising form of catering on his behalf these days is the inflation of his literary reputation. Several writers told me that the price of the ticket to be in the Rushdie camp has now come to include saying reverential things about his writing.

“It has at all times been important to Rushdie that The Satanic Verses is defended as a work of art,” says Blake Morrison, literary editor of The Independent and a friend of the author’s. “To Rushdie it’s not enough to say, ‘Well, we don’t like the book but we defend his freedom to have written it.’ To him that’s the remark of an enemy. He wants people to believe it’s a great book as well.” Again, there is a political logic at work, the sense that if one said, “He’s overrated,” or, “He’s a nasty satirist,” Rushdie could lose his protection, Rushdie could die. “In a sense nobody is allowed to speak freely,” says one London publisher. “He has become quasi-canonized because of his situation.”

When I interviewed Fay Weldon, I asked her about turning Rushdie down for the Booker Prize years ago. She seemed to want to undo the judgment. Rushdie can “just outwrite the kind of writers that we all tended to be,” she said.

“If Muhammad goes out into the desert and all kinds of things are revealed to him,” she continued, “Salman goes into his own sort of desert and things are revealed to him. And this is a very strong element in what he writes, which is why he has the reaction to it that he does, which is why just as the ayatollah will condemn him for writing this, he will condemn me for not acknowledging it. You see?”

She fingered the embroidered pattern on the front of her white silk blouse. “It takes you a long time to get round to this point of view.”