Opening the door of his home on a minor terraced street in Brighton, Norman Cook, 35 years old, tall, balding, and who makes music under the name Fatboy Slim, introduces himself with the following question: “Are you a caner?”

Cook means: do I take drugs? Just off the train from London and with a head still nipping from the night before, I laugh and say, “I guess I’d put myself in that camp, yes.”

Cook, famously, is a card-carrying caner.

“I’m a useless party fiend who’s not a role model for anyone and who’s got nothing intelligent to say apart from ‘Let’s ’ave it’,” as he puts it.

Cook’s house is covered in yellow smiley faces, rave culture’s adopted symbol. There are smiley teapots, smiley mugs and smiley clocks. I can see that Cook manages his accounts on an outsized smiley calculator. Around the clubs of Brighton, the property is known as “The House of Love”, partly on account of its décor, and partly on account of its reputation as a place of hedonistic shenanigans.

“Whoever is DJing in Brighton invariably ends up here,” he says.

In an upstairs back room, I’ve interrupted Cook tinkering away on a new song. Cutting up bits of Dick Dale-style surf guitar with a thumping breakbeat and a looped sample (“Right about now, the funk soul brother/Check it out now, the funk soul brother”), the track is called “The Rockafeller Skank” and will soon become ubiquitous.

It is a Saturday afternoon in January 1998 and I have come to interview Cook for a magazine I’ve started working at, The Face. The plan is that Cook will take me clubbing around Brighton as a backdrop to my profile of him. We will visit a night called Mr Fabulous and Mr Mental Present: Fabulous and Mental!, among others.

But before we leave, Cook suggests a livener. On the back of a CD on his living-room table, he has laid out four lines of cocaine. But there are two of us.

“One for each nostril,” he explains.

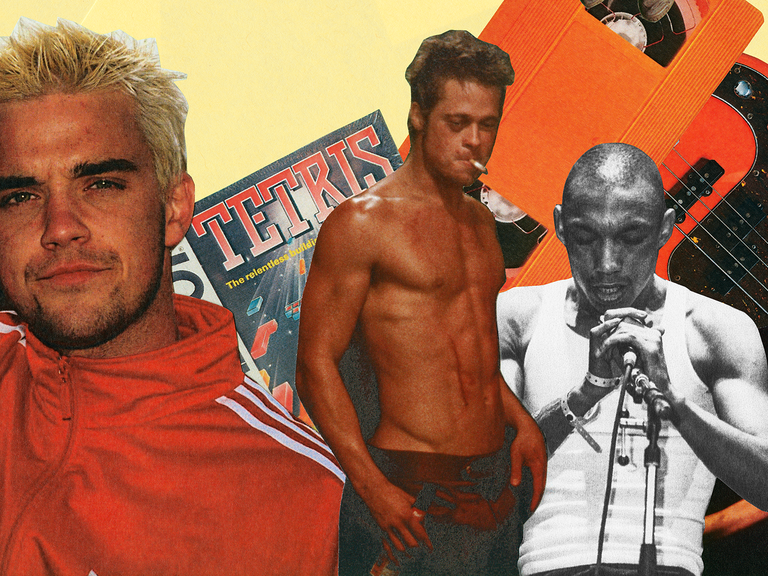

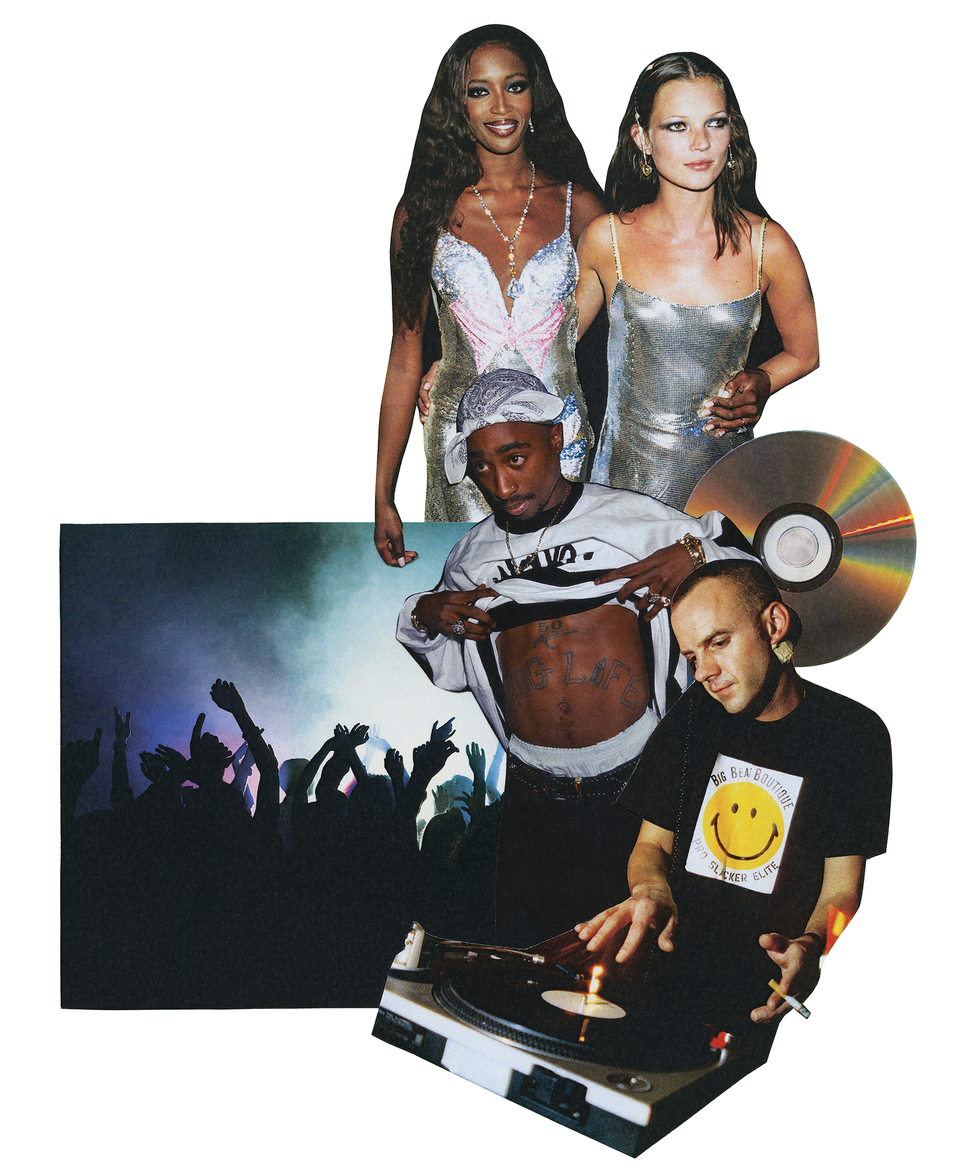

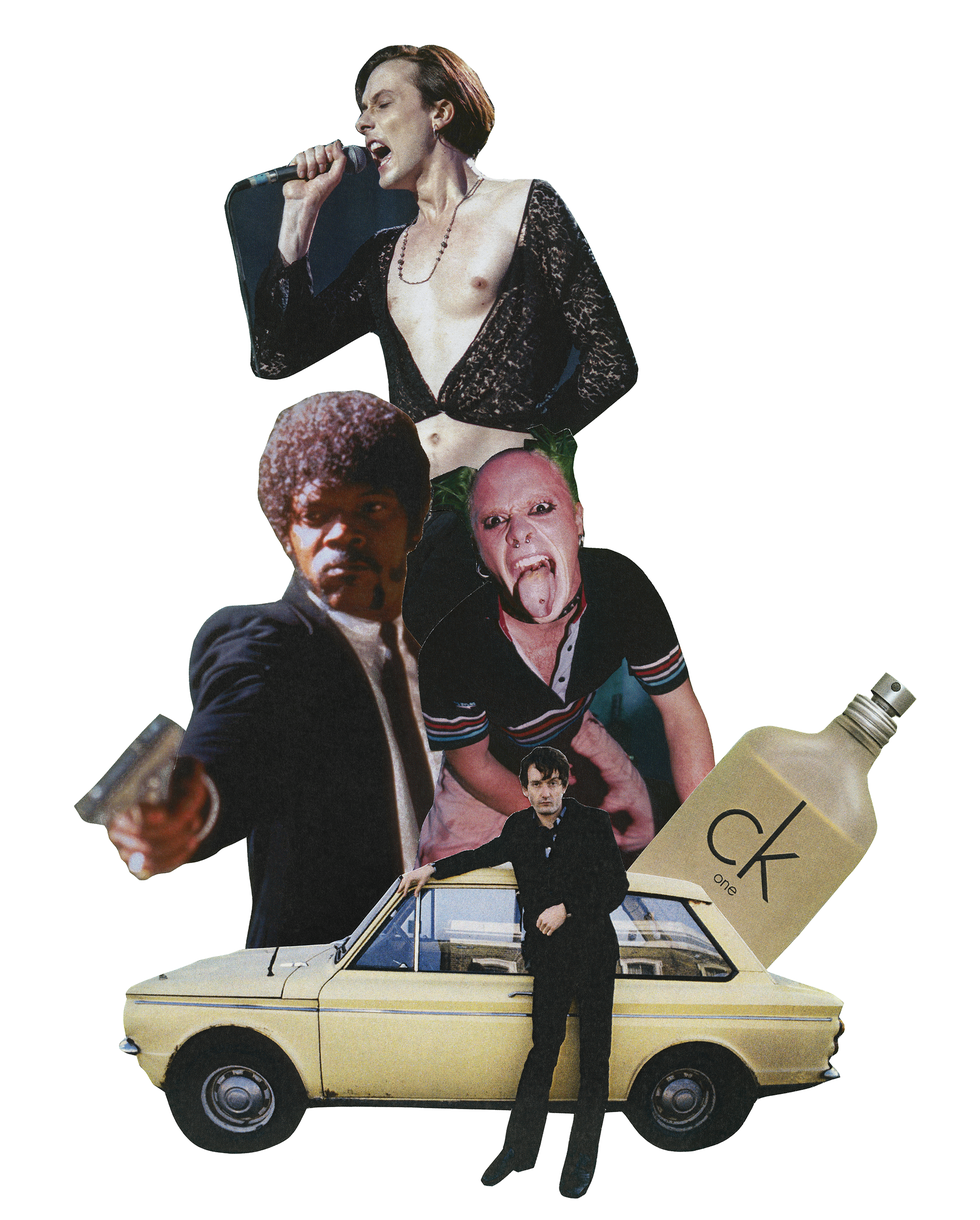

Today, Norman Cook is a reformed character. He entered rehab in 2009 and hasn’t touched drink or drugs since. But drugs run through the 1990s like the proverbial stick of Brighton rock. History dictates that clubbing as we know it became a thing in this country with 1988’s “Summer of Love”, but it was the next decade when everyone worked out how to monetise and make it mainstream. The era of superclubs like Cream in Liverpool and Renaissance in Mansfield. Of triple-mix CDs called things like Havin’ It Ibiza II Mixed Live by Alex P & Brandon Block. Of “superstar” DJs like Sasha and Danny Rampling. Soft drinks were advertised with rave graphics. Popular T-shirts included Hysteric Glamour’s “Junkie’s Baddy Powder” — in the Johnson’s baby powder font — and “Techno” in the Tesco font. Of Mondays when Radio 1 Breakfast Show DJs would talk nudge-nudgingly of overcooking it at the weekend. “Suicide Tuesdays” were a legitimate excuse for being in a foul temper at work.

Drugs haven’t gone anywhere, but I would suggest that today’s young people perhaps have a slightly more enlightened attitude about when and where to take them. They certainly don’t need to show off about them. But in popular culture in the 1990s, drugs were everywhere, all the time. Oasis, famously, were mad for them. Pop-dance band The Shamen went on Saturday morning kids’ telly with a song whose chorus literally went: “Es are good.” Brian Harvey, from the boy band East 17, told a radio interviewer that he’d recently taken a dozen Es, since ecstasy was a “safe drug”.

Later, Harvey ran himself over with his own car after, apparently, eating too many jacket potatoes and opening the driver’s door to be sick.

Why am I going on about drugs? I’m trying to remember myself… yes, that’s it. Because they are inseparable from my experience at The Face in that period, when I had a job at the magazine at the centre of the pop-culture universe. Before TikTok, Instagram, Spotify, Reddit, Reels, Stories, YouTube, Facebook, influencers, Grailed and Hypebeast, if you were under 30 and had an interest in pop culture, the place you found out about it was in magazines. Published monthly and sold in newsagents for less than £2.50, these colourful and glossy objects were nice to look at and told you what was what, and who was who — and were consumed in their hundreds of thousands. There were other titles covering similar territory — Sky, Q, Mixmag, Loaded, i-D — but the don was indisputably The Face. Better-looking, better-written, smart without being pretentious and often very funny. Like thousands of other people of a certain age, I had grown up outside London, using it as a monthly teleportation device into a world of glamour, cool and excitement that was not my parents’ sitting room. It reported culture but created its own culture, too, helping launch the careers of a generation of photographers, writers, stylists, editors and commentators including Juergen Teller, Steven Klein, Venetia Scott, Ekow Eshun, David Sims, Corinne Day, Katie Grand and Chris Heath.

People have plenty of places to get their get their culture and style “fix” these days. But it is perhaps instructive that the 1990s revival is such that The Face itself relaunched in 2019, having been shut for over a decade — surfing a wave of industry goodwill, perhaps, from those very people who’d grown up reading it. I, for one, was obsessed with it, to the point of ringing up the receptionist at Exmouth House in east London to check an on-sale date. Or, on another occasion, to be greeted with a suitably withering response — I’d have been disappointed with anything else — to asking what trainers Jay Kay from Jamiroquai was wearing in a photoshoot and where I could buy them. (Puma States, from Duffer of St George. A bus trip to London followed, only for me to ruin the shoes at an Ibiza foam party.)

So it felt like winning a competition when I was sent there on a work-experience placement from a postgrad course at City University, and then offered a job. I was given a desk in the corner of then-editor Sheryl Garratt’s office. One of my first assignments was to go through an enormous box of club flyers that had been sent in, to see if there was anything that might be worth The Face covering. Garratt, a club evangelist herself — her reissued book Adventures in Wonderland, the definitive story of the scene, was longlisted for the Penderyn Music Book Prize in 2021 — said that I was now The Face’s “Clubs Editor”. The job description was fluid. In practice, it meant I could get into any club I wanted to, for free, with as many of my mates as I liked. Doubtless my “reviews” were generally positive. As soon as the promoters knew The Face had arrived, we’d be whisked into some backroom — desk piled high with the night’s takings, Guy Ritchie-film style — and given preposterously strong ecstasy. I was 24 years old. This was my first job.

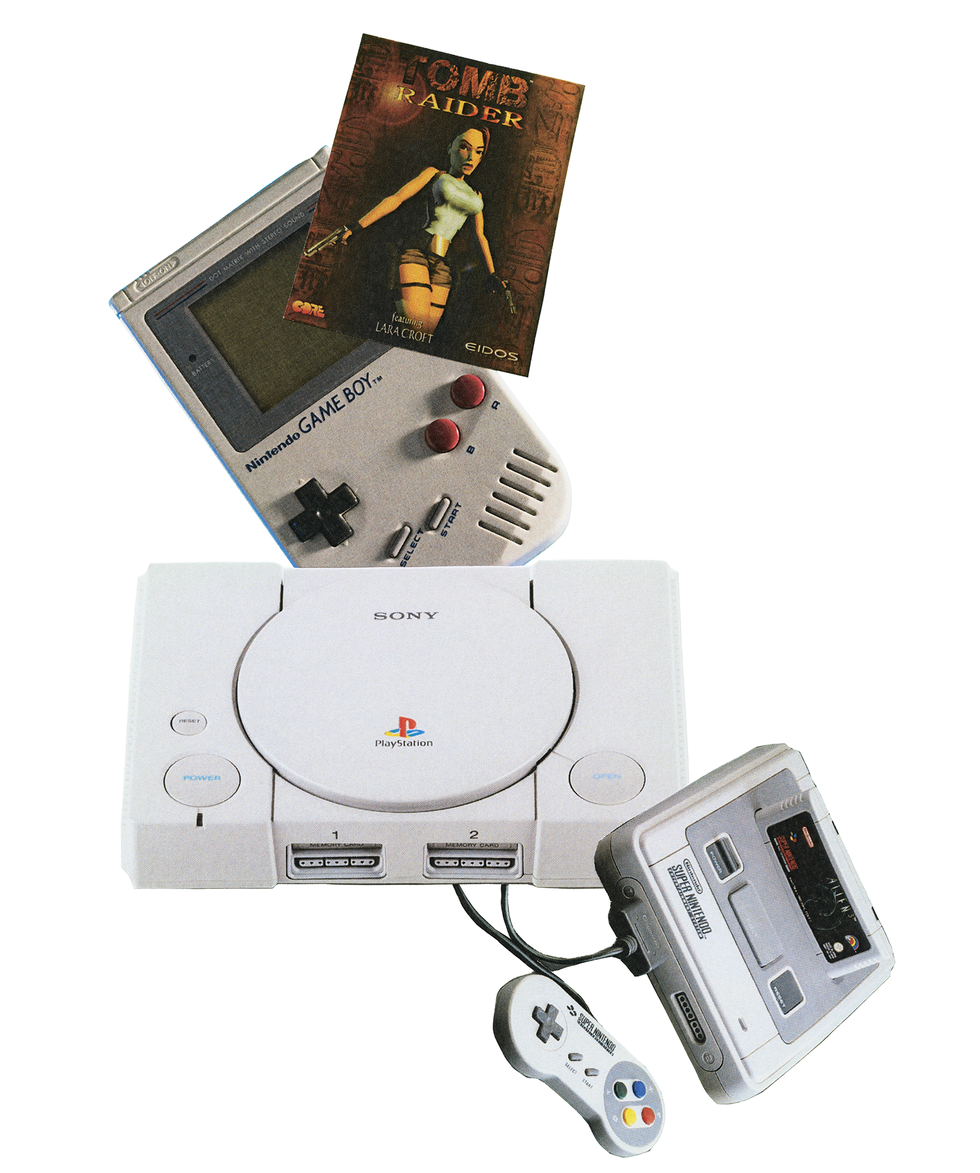

When I wasn’t off my napper dancing to “U Sure Do” by Strike or “Yéké Yéké (Hardfloor Remix)” by Mory Kante, there was some actual journalism to have a go at. People tend to refer to The Face as a “1980s style mag” — publishing legend Nick Logan, formerly of NME and Smash Hits, launched it in 1980, inventing the style press with a mix of popstar interviews and street and club-fashion reporting that he produced independently. But its most successful period was during the 1990s under Richard Benson (now an Esquire editor-at-large), who replaced Garratt. This has a lot to do with Benson’s brilliance as a cultural observer. After some persuasion, the people at PlayStation decided that his idea to put a render of Lara Croft on the cover — Tomb Raider had become the biggest thing in video games, scarcely the usual concern of the style press — was a good one. Commissioning an underground comic artist named Jamie Hewlett to do a monthly strip five years before Gorillaz released a single, was another.

But it’s also to do with the way culture exploded back then, something that magazines were uniquely placed to cover. Suddenly, an indie guitar band like Blur could be dressed in shirts and ties and photographed for the cover in a set of high-concept images as boardroom bankers. Or Kurt Cobain in a tea dress and chipped red nail varnish. In 1997, we put the Spice Girls, then the world’s biggest pop band, on the cover, wearing bikinis. The issue sold out. Nick Logan appeared on the shop floor asking if there was any way to reprint it.

These days, all culture is everywhere all the time — you’re as likely to hear about the hot new band on The Graham Norton Show as you are in Vice — but back then, plucking out an aspect of it and giving it a magazine-cover makeover was a statement that meant something.

In the 2020s, the 1990s are back in fashion. Harry Styles performed at the 2021 Grammys in a yellow checked Gucci blazer and lavender feather boa, a look apparently inspired by Alicia Silverstone’s character in 1995’s Clueless. Pam & Tommy, the story of a VHS sex tape stolen from the then-couple’s home and uploaded onto a nascent internet, has been one of TV’s big talking points. The Matrix and Scream are back in the cinema. Friends is bigger than ever.

In fashion, you can take your pick from the return of plaid shirts, biker jackets, cargo pants, bucket hats, combat boots, overalls (with one strap undone), baseball (sorry, “dad”) caps and outsized windbreakers.

Part of this is the familiar 20-year cycle. The 1950s came round again in the 1970s, the 1970s were hip in the 1990s. It’s long enough ago now that what’s old seems new again. People who came of age in the 1990s now hold positions in the media where they can spend their budgets on things they feel nostalgic for — hence the Beavis and Butt-Head relaunch and Netflix’s upcoming That ’70s Show reboot… That ’90s Show, presumably.

There’s also a run of books. Chuck Klosterman, the celebrated US critic who in the 1990s worked as a music writer for Spin, has just published The Nineties, 370 pages of thoughts on everything from Daniel Clowes to Rosario Dawson. Closer to home, Jane Savidge has written Here They Come with Their Make-Up On about the band Suede, a follow-up to Lunch with The Wild Frontiers: A Story of Britpop and Excess in 13 and a ½ Chapters. With John Best, Savidge co-founded the music PR agency Savage & Best and was pivotal in instigating Britpop, representing not just Suede but Elastica, Pulp, The Verve, The Auteurs, Menswear and loads of others. I went out on my first “business lunch” with Savage & Best, terrified and mute during my first week at The Face, and sat opposite Jane — who was then called Phill — with her geometrically bobbed blonde hair and hoop earrings, genuinely unable to work out if she was a boy or a girl. Ahead of her time, that Jane Savidge. Unlike the ladettes, who thankfully came and went. Though I can’t help but smile at how Denise Van Outen’s new memoir, A Bit Of Me: From Basildon to Broadway and Back, details her “hedonistic 90s heyday” — “a whirlwind of Concordes, private jets and arriving at Glastonbury in a helicopter” — while dating Jay Kay. And flashing her bra at Prince Charles backstage at Party in the Park while he was shaking hands with Steps. (Flashing your bra at Prince Charles backstage at Party in the Park might just be the most 1990s activity it is possible to imagine.)

But it’s not just the folks who lived through it. A generation who were in nappies in the 1990s are nostalgic for it, too. The video for 2018’s Charli XCX and Troye Sivan song “1999” included references to the blue iMac G3, Steve Jobs, Britney Spears, Eminem, The Sims, The Blair Witch Project and the music videos for TLC’s “Waterfalls” and The Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It That Way”. On the cover, they’re dressed up as Neo and Trinity. The Instagram account @90sanxiety (sample posts: a Nokia 3310 displaying the game Snake; beautiful Titanic-era Leonardo DiCaprio) has 2.3m followers. This year, the fashion press has been cheerfully reporting on a style called “indie sleaze”. Lumped in with the 1990s revival, it seems to take in everything from The Libertines (who broke through in 2000), Hedi Slimane-era Dior Homme (2001-2007) and The New Romantics (the 1980s). For some reason, Jeremy Scott, today of Moschino, is in there too.

“The look is a messy amalgam of 1990s grunge and 1980s opulence with a slightly erotic undertone, topped off with an almost pretentious take on retro style,” explained Vogue in January. Right, gotcha.

Slightly more usefully, TikTok “trend forecaster” @oldloserinbrooklyn, who apparently came up with the name, suggests that indie sleaze is born from Covid. “We’ve been in lockdown for essentially two years, and people are really craving community and creativity. I feel like, with the indie sleaze subculture 15 years ago, community, art and music were so powerful — that’s what bought people together. I think specific elements, more so than fashion, will become prevalent, as well as the style of photography,” she says. In other words: we’ve all been locked up, now let’s party.

I think @oldloserinbrooklyn is onto something here. Community and creativity were super powerful in the 1990s. I would happily make the case for that being what made it the last great decade.

In cinema, it gave us Quentin Tarantino, whose Reservoir Dogs (1992; much bigger in the UK than it ever was in the US) and Pulp Fiction (1994) kicked the gate down for Wes Anderson, Alexander Payne, Richard Linklater and a new generation of style-savvy filmmakers who surfed the arthouse/commerce line. Disney came back from the dead with the first two Toy Story movies (1995; 1999). Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996), the adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s 1993 book, remains a cultural North Star. Literary young bucks Nick Hornby (Fever Pitch, 1992), Dave Eggers (Timothy McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, 1998) and Douglas Coupland (Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, 1991) became superstars.

In art, there was Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, Tracey Emin, Gary Hume and the rest of th YBAs. The pop video became a three-minute-thirty-second art form in itself, launching the careers of Spike Jonze, David Fincher, Michel Gondry and Chris Cunningham.

Never mind cut-and-paste indie sleaze: my memory of 1990s fashion is that it was dominated by actual mavericks and one-of-a-kind geniuses, designers who reimagined the idea of what clothes can mean. Alexander McQueen, with his shows as one-off 10-minute art installations; Raf Simons turning the imagery of cult bands like Manic Street Preachers and Kraftwerk into layered, hooded and sculptural streetwear; his luxuriously bearded Antwerp cohort Walter Van Beirendonck, who made pullovers that seemed more like neon provocations than something to keep the cold out.

I sat in the audience at London’s Sadler’s Wells theatre one June evening in 1999, and my jaw hit the floor with everyone else’s as Hussein Chalayan showed a collection of womenswear that effortlessly untied into wooden furniture. The show notes say it was inspired by a nomadic and portable existence. It’s hard to think of a more au courant idea than that in 2022.

It’s mind-bending to try and get your head around now, but the luxury fashion houses, the conglomerate behemoths with all their power and advertising spend, barely existed in the 1990s. Prada opened its first menswear shop in 1998. The idea of fashion companies solidifying their bottom line with airport concession fragrances, leather luggage dongles and logo T-shirts would have been considered irredeemably naff.

Fun and optimism were everywhere. Multi-culturalism and alternative media were on the rise. Gay culture entered the mainstream. Advances in technology, including cable TV and the World Wide Web, offered new possibilities of connectivity and togetherness.

Steven Daly and Nathaniel Wice’s 1995 book Alt Culture: An A-Z Guide to 90s America now reads like a brain dump of positive ideas: snowboarding, Peta, gay marriage.

Baby boomers Tony Blair and Bill Clinton had swept into office on a wave of youthful optimism to clear away the hangover of 1980s conservatism. One of them played electric guitar. The other one played saxophone and wore Ray-Bans. Madonna invented the live-show-as-unmissable-event with her Blond Ambition tour (1990) and the subsequent Madonna: Truth or Dare documentary-of-the-tour (1991), for which one could make a fair claim that it invented warts-and-all reality TV and rewired how we consume celebrity culture. (Backstage, Kevin Costner tells Madonna, “I thought it was neat.” Turning away, she responds by sticking her fingers down her throat.) No Blond Ambition, no grand pop spectacle tours from the likes of Katy Perry, Beyoncé and Lady Gaga today.

The quality of television improved exponentially: Twin Peaks (1990); The Sopranos (1999); The Day Today (1994); Queer as Folk (1999); South Park (1997). The TV event of the decade wasn’t a TV show, but the world’s then-longest and slowest televised car chase — when, in 1994, America plus a global audience of 95 million watched OJ Simpson being driven along 60 miles of US freeway in a white Ford Bronco, sitting in the back seat, occasionally sobbing and holding a gun to his head. Its speed did at least give people enough time to get down to the side of the road with home-made banners: “Free OJ”, “Run, OJ, Run” and “The Juice is Loose”. He had just been charged with the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman, who had been found stabbed to death outside Brown’s condominium on 12 June 1994. (Simpson was later arrested, tried and acquitted for the murders). He was now heading to the airport; items found in the car included $9,000 in cash and a fake goatee.

Those two hours of TV arguably changed our perception of celebrity, pop culture and criminal justice forever. (The 2016 series The People v OJ Simpson: American Crime Story was a mesmerising reminder of how much and how little has changed in the intervening 22 years.)

Now, OJ’s flight would be livestreamed on Twitter, or TikTok. In the 1990s, the internet barely existed. My memory of “getting” it at work at some point around 1996 or 1997, when it was dial-up, was that I couldn’t think what to use it for. I remember looking up the band Underworld, because I liked them and they seemed quite future-y, and getting a page of black and white graphics. Amazon launched in summer 1995, selling books.

“Do you have a favourite site on the net?” I asked the designer Helmut Lang, in the August 1999 fashion issue. “Well, actually, no,” he said. “Not really. But for me, the whole internet thing is like when we got introduced to the fax machine. Our lives changed completely. I think that what happened a hundred years ago with the Industrial Revolution is happening again now. It’s the Technical Revolution.”

It was also a time when everything was beginning to move out of its own lane. Björk dated Tricky. Goldie made a song with Noel Gallagher. Hands down the greatest rapper of the decade was a dirt-poor Detroit kid called Eminem, who was white. London clubs like Trash on New Oxford Street and The Heavenly Sunday Social on Great Portland Street delighted in playlists that pitched David Bowie’s “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide” next to Daft Punk’s “Da Funk”, or The Temptations next to Schoolly D. On The Face trips to Ibiza (yes, we all went on holiday together) the CD we played the most was The Verve’s Urban Hymns. Fatboy Slim, The Chemical Brothers and others found success in marrying the beats of hip-hop with the riffs of rock. “To me, having the Stooges and Salt-N-Pepa on at the same time, that was Trash,” David Dewaele, one of the club’s DJs, later commented. Thus, “bootlegging” was born — not-strictly-legal vinyl mashups of Destiny’s Child’s “Independent Women Part I” with 10cc’s “Dreadlock Holiday”, for example. Or, indeed, the Stooges’ “No Fun” over the top of Salt-N-Pepa’s “Push It”. Don’t knock it til you’ve heard it.

The 1990s were and will always remain the zenith for bands selling records. The knock-on effect for journalists was record company money for press trips. Why profile Goldie at home in north London, when you can fly over to Florida and interview him on tour there? And also watch him blag a load of jewellery, grills for his teeth and clear the Stüssy store of so much free gear that he couldn’t close the boot of his limo.

Money seemed to be everywhere. You can stick a pair of combat boots and a “dad” cap on and call it a 1990s revival if you like, but there’s no way being 24 in 2022 can be like being 24 in 1996. No one had a crippling student loan, for starters. I don’t recall ever having any money, but that didn’t seem to be a problem. A silly job in the media means you get invited to all sorts of corporate-sponsored events promoting some new film or football boots — believe me, there is such a thing as a free lunch — and that’s as true now as it was back then, to a point. When PlayStation launched a new console, it did so by hiring LA’s Dodger Stadium, filling it full of top rock acts and fine chefs and flying over the world’s media. Mini Kiss played! I once went to Sydney Opera House to review Massive Attack. (They were very good. Of course they were.) Clarks took me to Japan for the opening of a new shoe shop. Is this ethically right? Almost certainly not. But it was quite the time to have the job I had.

It wasn’t just that job. After the recession of the early 1990s, the decade was a boom period of unprecedented economic growth. Work was plentiful, inflation fell and poverty was on the downward curve. Nobody lived anywhere decent — I recall going back to Richard Benson’s house after a night out, expecting a home befitting a high-flying style magazine editor, and ending up in some two-room dump in Finsbury Park furnished exclusively by tottering Ikea shelves of CDs. Really, what else did you need back then? No one stayed in anyway. New bars, cool shops and fantastic clubs opened every week. No one went to the gym after work. There weren’t any gyms, or at least, none of us knew of them.

The events of 9/11 were in the future. There was a series of wars in the former Yugoslavia, but that felt like something that was happening very far away, with next to no impact on our lives. In London, flash new buildings appeared in Canary Wharf, and the city was granted its own municipal authority. Pretty soon, it would even have its own mayor. It wasn’t all fun and games, though. Not every story was a happy one, and not everybody escaped unscathed.

Lad culture was in full swing, and the style press was far from immune. Photographers including Terry Richardson crossed the line from fashion photography into pornography — The Face was complicit in publishing some of it but also reported on it, identifying the trend as “fleshion” and spending 3,000 words wondering quite what it all meant. The skincare company Sisley ran a campaign by Richardson that featured women on a farmyard squirting milk into their mouths from cow udders. The 1995 Larry Clark movie Kids, written by a 19-year-old Harmony Korine, doesn’t look edgy now. It looks tawdry.

Our publisher died of an accidental overdose. His funeral was the first time I’d heard pop music in a church; a stark reflection of his age, his coffin was carried out to Massive Attack’s “Unfinished Sympathy”. Another member of staff contracted HIV. When we went to see him in hospital, the unspoken understanding was that we were saying goodbye. (He’s still going strong today.)

The police were called after a staff member had taken someone back to the office to have sex — they’d fallen off a wall and knocked their teeth out. We made it onto Crimewatch when some diamonds for a fashion shoot got nicked. The entire archive of back issues was stolen when it was left in a van by a documentary maker who wanted to make a film about The Face.

I was made editor in 1999, and within 18 months had some sort of breakdown of my own — in true of-its-era behaviour, becoming an outpatient at The Priory. As Jarvis Cocker says in the 2003 Britpop documentary Live Forever, “You don’t often hear people say, ‘Oh, since he’s been taking them drugs, he’s such a nice person!’”

But there were plenty of triumphs. Sending The KLF to report on the Labour Party Conference. Sending Caitlin Moran to report on Saturday morning kids’ TV. Sending Post-it notes to as many famous people as we could think of and asking them to send us a doodle back. Kate Moss drew herself naked. Damien Hirst drew a spurting cock. Of course they did.

And missed opportunities, too. Brad Pitt asking to be put on the cover for 1999’s Fight Club, and us saying we wanted his co-star Edward Norton instead. (Possibly the last time anyone in the media turned down Brad Pitt.) The staff pushing for a new artist called Grayson Perry and me insisting, “We’re not doing a fucking potter.” The iPod launching with the “1,000 Songs in Your Pocket” adverts and us responding by sticking it “down” in our monthly barometer of things we rated and hated.

“Who likes 1,000 songs?”

In many ways, the decade seems a very long time ago. (It was!) The world at large, and my world, the world of London media, has changed beyond recognition. It’s been a good few years since an interview subject offered me drugs. I haven’t seen Mini Kiss at many recent events. Clarks is presumably spending its money more wisely than blowing it on business-class flights to Japan for freeloading British journalists.

Even Norman Cook had to dial down the hospitality in the end. People had started doing lines off the railway tracks at the back of his house; one of them was rushed to hospital with his hair standing on end and his clothes on fire.

So, 90s revivalists: don’t say you haven’t been warned.