He remembers a time in France in the 1980s, turning up on a Monday lunchtime at a restaurant a well-connected Parisian friend had recommended, south of Avignon. The place was closed. “We told them our friend’s name and they said, ‘Oh! You must come back tomorrow.’ And we said, ‘We can’t, we have to leave.’ And they said, ‘Well, join us then.’ This was their day off. This was their family meal. And we sat with them. And they produced pâtés and stuffed mussels. They cooked lamb in the wood-fired oven. They brought out freshly made goat’s cheese. And rosé wine. And the mistral was getting up. And it taught me so much about the difference between the French and English approach.” The generosity, the conviviality, the warmth. He hasn’t forgotten it.

He remembers, many times, going to Paris alone, eating in the great brasseries. “La Coupole, Bofinger. There was another one up near Pigalle, which I loved. To sit in those restaurants, and even Terminus Nord. Just to sit there. Or to be on Saint-Germain, in Café Flore, or Deux Magots, or Brasserie Lipp.” These places were transforming for him. They informed everything he has done.

He remembers another time in Paris, arriving at a hotel on Saint-Germain in the early afternoon, “thinking, ‘We’ve got a big dinner later, let’s go and grab a salad at Flore.’

“We walked in, and we said, ‘Can we have a table for two?’ And the guy said, ‘Bien sur.’ And he was about to turn away and then he rolls his eyes and says, ‘Fumer ou non-fumer?’ Because they’d just changed the law, you had to have a no-smoking section. So we say, ‘non-fumer’, we go in and you have those tables that are so tightly packed together that you can’t get in unless you pull the table right out and I went in and sat on the banquette and he was pushing the table back in and my wife was sitting down and I looked to my left and these two people here, very close, were smoking, and I looked to my right and the two people there were smoking and I looked up at him and raised my hands as if to say, ‘?’ And he says, ‘Oh.’ And he reaches into his pocket and pulls out a no smoking sign and places it on our table. It was that sort of confidence. I thought, ‘Yes!’”

He admires this still. The insouciance of it. The panache.

He remembers another time, sitting by himself in a restaurant in Budapest as a violinist went around the tables, “the kitschiest thing, tears streaming down my face, the emotion of it.”

Further back, he remembers the Sea Spray Café, in Burnham-on-Sea, in Somerset, the town he grew up in, in the 1960s. He was 14, and he got a Saturday job selling ice cream to the people who came from the Midlands to holiday on the mud flats there. His friend Mark’s parents owned the café, an old greasy spoon. For a shy boy, tall and awkward, this was the perfect job, with a counter to separate him from the customers. That was crucial. “It was protection.”

He remembers the Holimarine Club, also in Burnham, where he worked as a barback. “What I found there is, I would watch people, for hours and hours. Often falling in love with them, like the singer in the band at the Holimarine. I think that’s how my life has been, watching. And always feeling a complete outsider.”

That feeling comes from his parents, he thinks. They’d moved from Perry Bar, in Birmingham, to the Somerset coast, seeking to make more of their lives. His father had wanted to be an architect, but the family couldn’t afford to pay for his studies and instead he ran a building company, “miserable throughout his working life”. He remembers a hotel in Burnham where his mother worked as a secretary and where, occasionally, the family would get a meal from the management. “You can imagine: tomato juice as a starter.” No one showed an enthusiasm for food. If it couldn’t be put in a pressure cooker, his mother wasn’t interested.

But she gave him something more important. “She understood I was going to languish at the local grammar school in Weston-super-Mare.” Another of her secretarial jobs was at a prep school, and it’s there that she heard of a famous old boarding school, Christ’s Hospital, in Sussex, where parents paid fees according to their income. “It was a wonderful lesson in egalitarianism: everyone from fallen aristocracy to bright boys from the East End, all of us melded together. It’s something that is fundamental to me.”

His shyness had not abated. Just mention of the word King, his surname, in any context, caused him to blush. Christmas carols were a nightmare: “Born is the …”, “Glory to the newborn…”, “We three...”, “Good… Wenceslas.” Blush, blush, blush, blush. He was a bit of a loner, but he loved that school. Still, his experiences of food, of hospitality, were strictly rationed. He became fascinated with food in literature. It was his only exposure to a love of cooking and eating well.

He remembers that, after finishing their A-levels, he and his contemporaries were granted a 24-hour exeat to celebrate. Most of his friends went up to London, to the Marquee club. He went on his own to Petworth, the National Trust estate, and had lunch at the hotel that was there then. He remembers rollmop herring to start and then — he thinks — trout. “Bad choice, really, fish and fish.” But it left him wanting to try restaurants. “Between the ages of 18 and 25 I spent virtually all my income on going to restaurants rather than pubs or bars, and often by myself.” After his fish-and-fish lunch he went into Petworth House to look at the Turners. Art and artists would be important to him, too.

He remembers he’d been offered a place at university, but he thought he’d try his luck in the City, as many graduates of Christ’s Hospital did. He got job at a merchant bank, Kleinwort Benson; £21 a week, working in the investment department. A dead end. The most he got out of it was an enjoyment of gambling.

He remembers the Epsom Derby, 1973. He got a tip on a horse. 33-1. It won! The adrenaline and excitement were so great that that evening, when he went with his flatmate and her new boyfriend to see Last Tango in Paris, at the Prince Charles in Leicester Square, he couldn’t focus on the action on screen. “Everyone was excited to see this unexpurgated sexual odyssey and all I could think about was Morston winning the Derby.”

He remembers how games of chance dominated his life. He fell under the spell of a cult novel, The Dice Man, by the pseudonymous Luke Rhinehart, very modish at the time. Like the antihero of that book, he made decisions on the throw of the dice. He turned down a place at Cambridge on that basis. “I regretted that deeply.”

He remembers not knowing what to do with his life. “I didn’t think I’d be a great architect or performer or writer or anything like that. I was following my nose.” He went to see a careers advisor. They said he should be an accountant. He said he’d be too bored. Unless he could be a turf accountant? It was a joke. They said, yes, perfect, do that. “I said, ‘Oh, forget it.’”

Meanwhile, he worked at a wine bar in Chelsea. And for a Frenchman who imported wine and had a restaurant where they served cassoulet. He wasn’t in love with it. He worried he should quit hospitality, find something else to do.

He remembers a man who ran front of house at Joe Allen, the London outpost, then newly-opened, of the Manhattan restaurant. This guy was accomplished, a Harvard graduate, a Rhodes scholar. “This was 1978, 1979. I was 24, 25. And I said I want to get out and he said no you mustn’t. He counselled me, like a therapist. ‘What do you like about the business?’ I said I like restaurants. ‘What sort of restaurants do you like?’ I said big restaurants. He said, ‘You’re going to come and work at Joe Allen.’ I said I can’t do that. I’m a slightly uptight Englishman, I can’t work in a quasi-American speakeasy. He said, ‘No, no, no. You’re going to come and work here and we’ll teach you how to run a good restaurant. And more importantly, and I think you’ll get much more out of this, we’re going to teach you how not to run a good restaurant.’” He became maître d’.

He remembers around this time he was going to Langan’s Brasserie, the happening restaurant of the moment. Mick Jagger, Liz Taylor, Francis Bacon. It’s where he got to know Chris Corbin, who was working there as a manager and who would become his business partner for 40 years. Peter Langan, the proprietor, along with his partner, the actor Michael Caine, was the biggest name in London hospitality then. An Irishman, larger-than-life, a drunk. “Of course, most of his behaviour was absolutely incomprehensibly awful.” But he learnt from Langan, as he learnt from all the restaurants he visited. How to do it. How not to do it.

He remembers that world of London restaurants he arrived into in the 1970s. “If you listen to commentators about that time, they will tell you how awful the food was in England. It wasn’t. It was awful up until about the mid-1960s. And to my mind, the transformation, which was a social as much as a culinary revolution, was because of Mario [Cassandro] and Franco [Lagattolla] opening the Terrazza in Soho. On one table you’d find potentially Princess Margaret and Anthony Armstrong-Jones, on another there might be David Bailey with Terence Donovan.” Royalty mixing with the young meteors of Swinging London. The dawn of the “classless society”.

He remembers the food, too. “In the early 1960s, if you wanted to find olive oil you went to the chemist. By the 1970s, things were changing.” He remembers Terence Conran’s Neal Street Restaurant, in Covent Garden, and Chelsea’s Hollywood Road, round the corner from where he was living. “It was full of really interesting places. And Chinatown was changing. Within 10 years, places like Langan’s Brasserie were as good in many ways as the French brasseries, in terms of culinary achievement.”

He remembers that a rigid social stratification was still in place. “It really was a strange situation. People were still a little scared of going out. I’ve had countless experiences of people being so intimidated in a restaurant. It was a class system and I hate class systems. I hate these impositions. I happen to always wear suits. But I abhor dress codes. I think that’s so unnecessary.”

Working-class restaurants were greasy spoons, like the old Sea Spray Café. Upper-class restaurants were in smart hotels. Michelin-star type places. Fine dining. Not really his kind of thing.

He remembers the response to the opening of Le Caprice, his first restaurant with Chris Corbin, on Arlington Street in St James’s, in 1981. Le Caprice — a famous old place fallen on hard times — was a new kind of restaurant: relaxed, chic, with none of the fussiness or formality of haute cuisine. It was a middle-class restaurant. The decor: 1980s art deco. A long bar, monochrome colour scheme, mirrors, rattan chairs, black-and-white photos of British stars of stage and screen. Outside, the logo in electric blue.

Establishment figures, stiff-upper-lip types — “prats” — told him it wouldn’t last a week. “Londoners did not get it. Middle courses, where you could have a starter or a main. That was never seen before. The idea you could have eggs Benedict in a restaurant like that!” For the first year, business was slow.

He remembers the New Yorkers who saved it. “It had disproportionate support from Manhattanites, either visiting or living here.” Le Caprice had opened a year after The Odeon, Keith McNally’s downtown hotspot, in New York. “Artists who were going to New York and seeing places like The Odeon were coming back and going ‘Hey! This is our place. This is where we’re going to be.’ And after a very quiet, rocky start, it took off. The fact that we took orders up to midnight, and we were there for the customers as opposed to the customers being there for us.’”

The prats were proved wrong. Le tout London descended, and they kept coming back. Media magnates. Advertising honchos. Culture majordomos. Fashion panjandrums. Politicians. Pop stars. Princess Di. Le Caprice was so famous that its maître d’, the suave and gracious Jesus Adorno, became almost as well-known in starry circles as his celestial clientele.

He remembers the 1990s. The Ivy, his second restaurant with Corbin, another old restaurant rescued from retirement, was the indisputable see-and-be-seen dining room of the decade. It was London’s theatre restaurant par excellence. Where everyone who was anyone in drama, TV, film, art and journalism, came to gawp and hobnob. The Ivy was so famous that the late AA Gill, the best and most celebrated restaurant critic in the country, wrote a book about it: “This is the room where people who are professionally good in rooms come to be good at what they are good at.”

The Ivy was decorated with art commissioned from Peter Blake and Howard Hodgkin, Michael Craig-Martin and Eduardo Paolozzi. And the dishes became classics: bang bang chicken; crispy duck and watercress salad; salmon fishcake; sticky toffee pudding. Outside on West Street, the paparazzi waited for Kate Moss or a Gallagher brother to emerge from behind the stained-glass windows. It was Cool Britannia’s canteen.

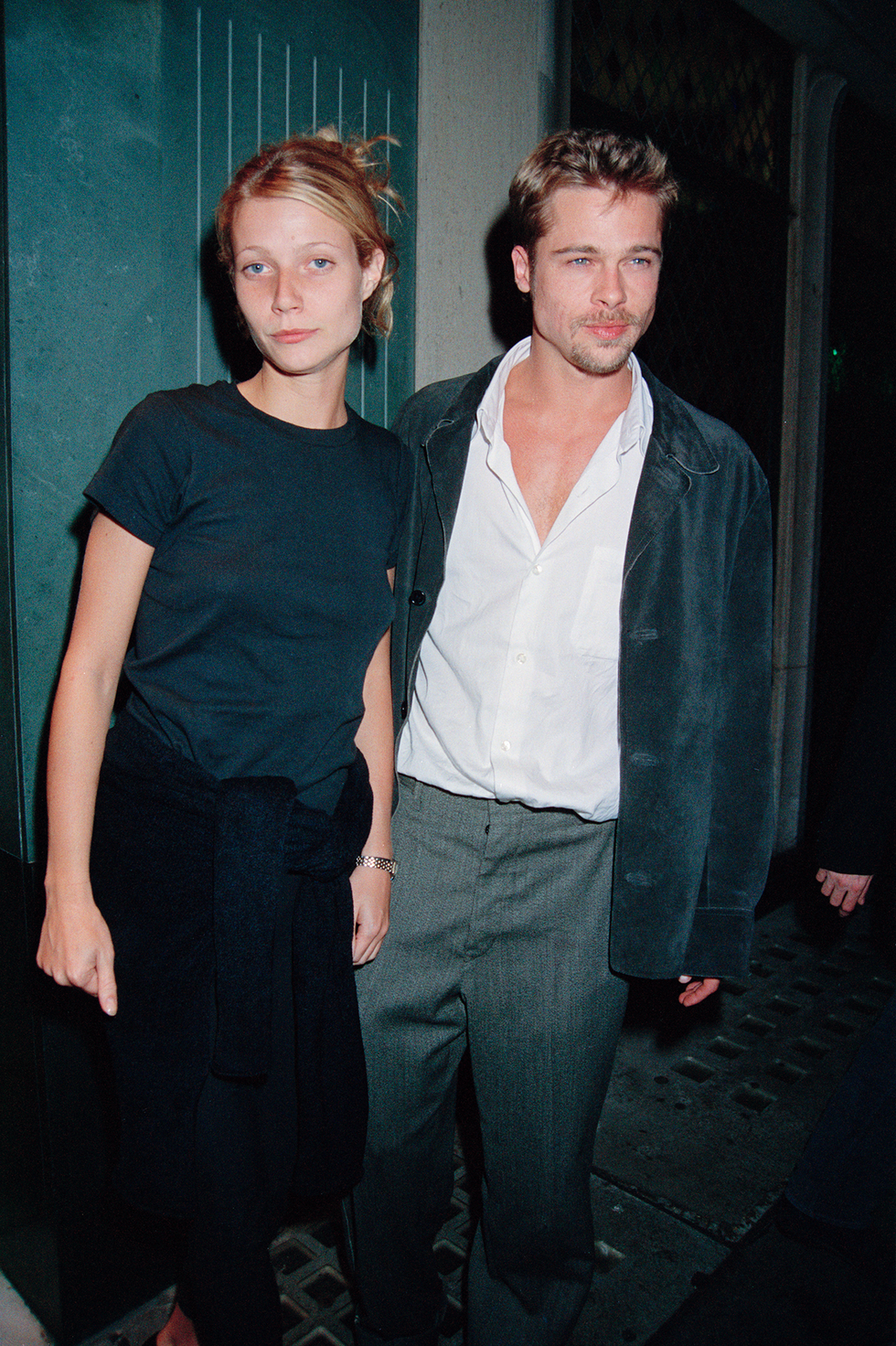

And now I begin to remember things, too, because at 19 years his junior, my own memories of eating out in London begin in earnest in the 1990s, in my twenties. As a junior magazine hack shinning up the moisturised pole, The Ivy was where my editor, who ate in these restaurants almost every day, might take me for champagne and shepherd’s pie. It was where a famous musician’s PR might buy me lunch to talk about a cover story, or a film star might agree to be interviewed for one. (More champagne and shepherd’s pie!) Every celebrity food group was represented. Not only Brad and Gwyneth and Tom and Nicole, but also Richard and Judy. Or Cilla with Christopher Biggins. The dream.

J Sheekey, the third of their places, another reboot of a dormant classic, London’s most refined fish restaurant, opened in 1998 in Covent Garden. That’s where I might take a date, hoping to impress. I took my mum. She was tickled to be seated at the next table over from Ralph Fiennes and Francesca Annis. These were restaurants, according to Ruth Rogers of The River Café, perhaps their only equal for star power, with a sense of occasion. Restaurants — Rogers again — where “you could always feel at home, but in a glamorous way”.

He remembers what it was like to have full ownership, and as a result complete control of his own restaurants and his business. And how that allowed him to do things in unorthodox ways. To do things with panache.

And he remembers why he and Corbin, who had become very ill, decided it might be time to cash out, to surrender some of that control. The restaurants were becoming increasingly profitable, but they were over budget and the business was fairly extended. “In 1998 they thought there was going to be a financial crash. We were worried about it. Chris had recovered from leukaemia and was in remission. There was no life insurance or anything like that. Luke Johnson, of the Belgo group, came along and offered us what seemed to be quite a lot of money at the time.” £13m. “We thought we should take some cash, carry on running the restaurants and then see what happened.”

He remembers that their money was tied up in Belgo group shares, and the value dropped precipitously. “I said to Chris, ‘Look, what are we doing this for? Let’s go.’ So we gave up. Chris wanted at the time to just invest in restaurants and act on a non-exec basis. I wanted to carry on. And eventually we did come back together again.”

He remembers that just two years later Johnson doubled his money, and then some, selling The Ivy, Le Caprice and J Sheekey to Richard Caring, the courageously coiffured rag-trade tycoon, for a handsome profit. (In the years since then, a rather glitzier Caprice Holdings has rapidly and one might say indiscriminately expanded; The Ivy, under Caring, has at my count 41 outposts, from Cardiff to Glasgow. It would be hard to argue that this compulsive cloning has added much to the lustre of the original.)

He remembers the first time he was shown inside a substantial art deco building, once a car showroom, then a bank, on Piccadilly, just along from The Ritz. It was called China House, and the ceilings had been painted brown and red, with big palm trees.

“I said, ‘Oh, banking halls, they never really work.’ But I took Chris down and said, ‘What do you think?’ And he said, ‘Well, you’ve always wanted to do a grand café, isn’t this the perfect site?’ I said, ‘Yes, that’s what I was thinking.’”

In 2003 it became The Wolseley, the most spectacular and successful dining room in London, said to have the highest-grossing turnover of any restaurant in Britain. It was inspired by the all-day cafés of turn-of-the-century Mittel-europa, like Vienna’s famous Café Central, as well as by Parisian brasseries between the wars. The late Irish designer David Collins transformed it into a monochrome marble fantasy of what a restaurant could be. The Wolseley became an institution, a London landmark, the most important dining room in the city. Breakfast, lunch or dinner, there was never a question, when you were sitting in it, that you had come to the right place.

He remembers The Wolseley as the ultimate expression of his egalitarian credo. For all that, from the first cappuccino of the morning to last orders at the bar, it was well stocked with famous faces, every day 17 tables were kept back for walk-ins. By no means was it all Stephen Fry and Joan Collins and AA Gill. You didn’t have to be famous or powerful or especially rich to eat there. At lunch I often just had the chopped chicken salad, fries and a Diet Coke, and no one blinked an eye. In and out in 45 minutes. (On other occasions I was not so abstemious.)

“The motto for me has always been: give people the opportunity to spend, don’t make it mandatory. The most interesting people in a restaurant at any given time are often the least affluent rather than the most. The most affluent support that. They are subsidising the people who give life to the place. Because I’ve been into these super-rich restaurants and clubs and they are so boring! People just sitting there spending lots of money because that’s their only means of expression.” Mentioning no names.

Part of his success has been his discretion. For 30 years from the opening of Le Caprice, he didn’t give a single interview. Now that he does, his conversation is unavoidably stardust-sprinkled with the names of the great and the good of haute bohemian London life.

He remembers Lucian Freud, who ate at The Wolseley six, sometimes seven nights a week, and for whom he sat, for one of the artist’s last, unfinished works. He remembers Harold Pinter, who set a play, Celebration, in a restaurant not unlike The Ivy, and based the character of the manager on him. (“He insists that standards are maintained up to the highest standards, up to the very highest fucking standards.”) And Diana, a regular at Le Caprice, with whom, he tells me, in a roundabout way, he once went go-karting. Beat that!

“Every time somebody high-profile comes in, it will lift a restaurant. What restaurateurs often make the mistake of, is thinking that the high-profile person wants Uriah Heep to come to the table, wringing their hands, obsequious and sycophantic. Actually, no. They want it to be very low key.”

From The Wolseley they built a second, bigger empire. The Delaunay, on Aldwych, another grand European café/restaurant, this time with a take-out counter. The mighty Brasserie Zédel beneath Piccadilly Circus, inspired by Chartier, the famous workers’ brasserie in Paris — all pink marble and plush banquettes, and outrageously reasonable prices; the three-course set menu, when Zédel opened in 2012, was £11.25. Café Colbert, in Sloane Square, an exemplary French café/bistro. Fischer’s, another, more compact Viennese-style brasserie in Marylebone, schnitzels, sauerkraut and Konditorei. Two neighbourhood brasseries in glossy London locales: Bellanger in Islington; Soutine in St John’s Wood. He tried to make an appearance in as many of them as possible, every day.

He remembers how, when there wasn’t a back story to his restaurants — when he wasn’t taking over an existing restaurant, as with The Ivy or Le Caprice — he would invent one. Fischer’s was founded, in his imagination, by Otto and Maria Fischer, one Jewish, one Catholic, escapees from Austria before the war. Pierre Colbert had been chased out of Paris having seduced the daughter of a Parisian café owner, and opened a bar in Chelsea in the 1930s.

I remember in 2014 being shown round The Beaumont, his new venture into hotels, and hearing the story — entirely made up — of Jimmy Beaumont, another refugee, this one from Prohibition-era New York, who came to London in the 1920s and opened a Mayfair bolthole with speakeasy-style restaurant: The Colony Grill. That was a rare example of one of his projects that didn’t work out as planned: the Barclay brothers bought the Beaumont in 2018, and he left them to it.

He remembers another rare failure: St Alban, an attempt at a more contemporary high-concept restaurant, modern European food in a Manhattan-style setting on Lower Regent Street. It opened in 2006 and closed three years later.

“We didn’t have absolute clarity about it. I’m a great believer in the maxim that a camel is a horse designed by committee. It was a bit of a camel. One of the great things is to learn from your mistakes very quickly. We were a bit slow. When I don’t listen to my instinct is when we make mistakes. You have to feel it. It’s almost a spiritual thing. I didn’t feel it about St Alban. I didn’t get the buzz on that building. And it was too big. We should have given some of the space to private rooms. We didn’t get the decor right. And we tried to get too clever. We were trying all sorts of new things, like not having a bar. Big mistake. All the components were really good. We knew what we wanted to do with the food. But it wasn’t enough. It didn’t gel. That, for me, was a very useful lesson. In the end we came out of it OK because we got a really good offer for it.”

In 2017, they had what appeared to be another good offer, from a Thailand-based, American-born billionaire, William Heinecke. His hospitality investment fund, Minor International, bought a 78 per cent stake in the business, for £58m.

“The sad thing with Minor is I think we both went into it with good intentions, but I was very clear from the outset that I didn’t want to roll out restaurants. I didn’t want to put the existing restaurants in hotels. I was happy to open new restaurants in hotels, but I didn’t want to roll out Colberts... But then, very soon after we got together, the talk changed to that.”

The story goes that he was unwilling to agree to Minor’s plans to franchise restaurants in Asia and the Middle East. A Delaunay in Dubai, perhaps, or a Wolseley in Saudi Arabia. And the story is not far wrong. “It’s fair enough. In the pandemic we were getting a lot of offers for franchises and I wouldn’t countenance it because I didn’t think we needed to do it. And so there was a difference of opinion, which I think is a great shame.”

Demanding immediate repayment of a loan, in 2022 Minor forced the business into administration. That April, the administrator held an auction.

He remembers how it played out. “It all ended up in the early hours of the morning. We were bidding against each other and my new investors were going above what they wanted to pay and there came a point when it was about two o’clock in the morning, they were in the solicitor’s office, I was at home.” He and his American backers tabled a bid. Minor offered a higher bid. He won’t be drawn on the figure, but it’s reported to have been £67m. “We said we can’t go any further, because otherwise I’m going to spend the rest of my life paying you off.”

Overnight, he lost the entire business and its assets, including all the restaurants.

Stephen Fry spoke for many regulars in a Tweet asking if it was “always going to be a world where the good guys lose and the greedy, soulless and mean win out?” The story was covered in forensic detail by all the British broadsheets and overseas, too. The New York Times noted that his “ouster” had “triggered a small earthquake in London’s social circles”. Many announced they would never set foot in The Wolseley or any of his former restaurants again.

It was, he recalls, “traumatic and upsetting.”

“I hated losing the restaurants, I hated having to walk away from the staff immediately without having the chance to even say goodbye. But, in retrospect, it was probably a blessing. It was the opportunity to start again.”

And now he is in the business of creating new memories, for himself and the rest of us. This year, he will turn 70. It looks like it might be the busiest and most exciting 12 months of his busy and exciting career.

“You have to open restaurants that you’d want to go to,” says Jeremy King. “The sort of restaurant I like is the grand café. What I love is the notion that somebody is sitting on a table having a cup of coffee, next to somebody at the next table who is having a three-course meal, next to somebody who is having afternoon tea, next to somebody who is having just a glass of champagne. That to me is the perfect scenario.”

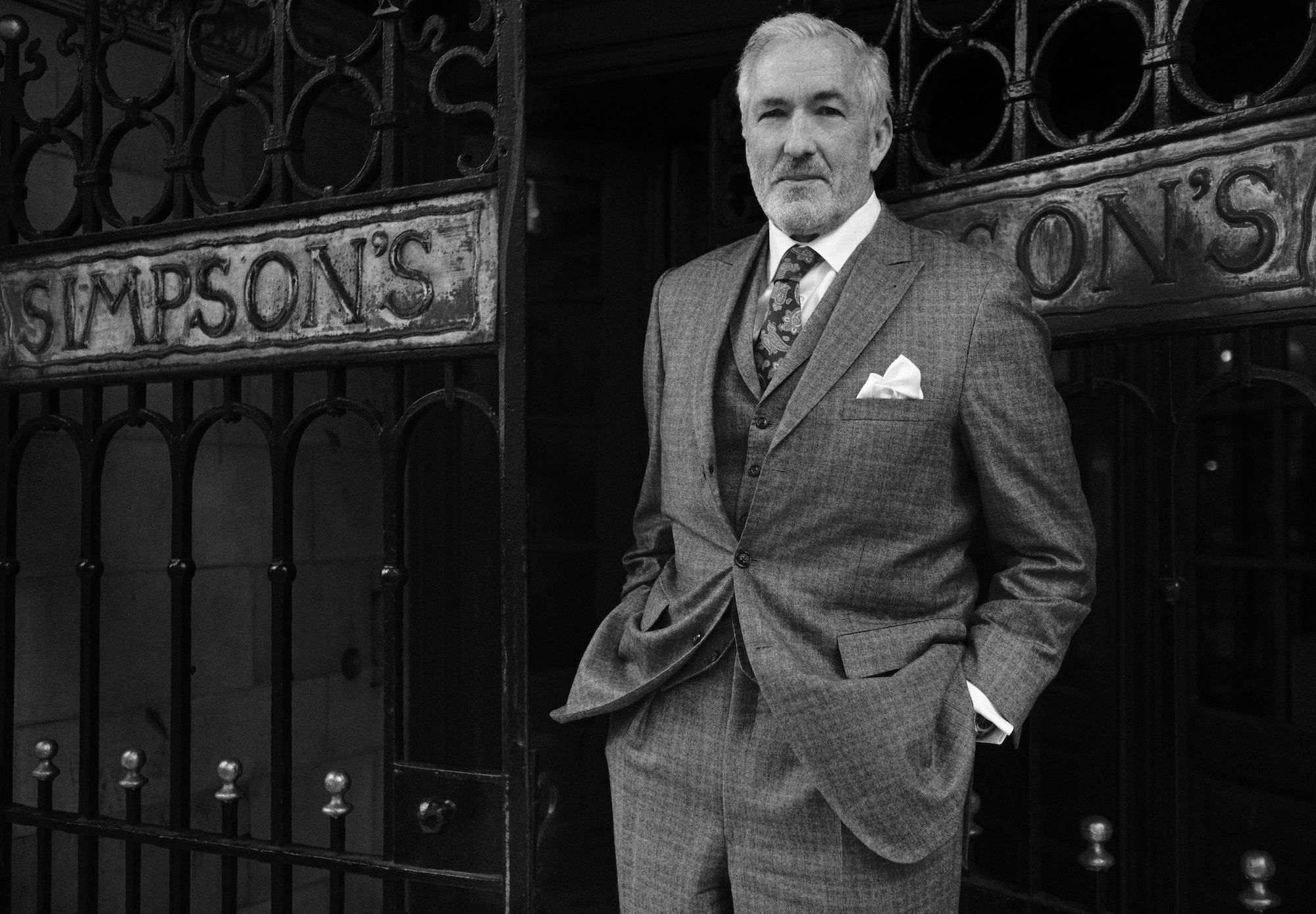

It's December 2023. We are talking in the dining room of one of the most fabled restaurants in London’s history: Simpson’s in the Strand, adjacent to The Savoy hotel. Charles Dickens ate here. So did Conan Doyle. It’s cold and dark and empty, today. But it won’t be soon. King has only lately taken possession of Simpson’s, an idea first mooted as long ago as 2000. It will be the third of a trio of restaurants he will open in 2024, as the empire builder prepares to construct a third restaurant group, to follow Caprice Holdings and Corbin & King. This time he'll do it alone, without Chris Corbin, who had for a number of years scaled back his involvement.

At 6’5”, with tidy white hair and a close-cropped beard, King can’t help being imposing.

He has three children, from his first marriage. Two daughters, Hannah Hauer-King, a theatre producer, and Margot Hauer-King, an advertising executive in New York; and a son, Jonah Hauer-King, the actor who played Prince Eric in the recent Disney remake of The Little Mermaid. He lives in Belgravia with his second wife, Lauren Gurvich-King, an interior designer.

He wears bespoke suits and drives a Bristol, collects art and goes to the opera. That irritating neologism “quiet luxury” might be applied to him. Ditto “stealth wealth”. For all the patrician air, the cufflinks and the pocket handkerchief, he is softly spoken and genial, not at all grand. But don’t mistake the smooth glide across the room for complacency. Here is a man of un-dimmed energy and ambition.

Since his exit from Corbin & King, he’s consulted for Jamie Oliver and Claridge’s. And been frequently sighted at Maison François, the St James’s restaurant to which quite a few who were once regulars at The Wolseley and The Delaunay have temporarily switched allegiance. They might have reason to head west on Jermyn Street again soon, when King opens the first of his three new restaurants planned for this year.

The first direct confirmation I received that a return to the fray was in the offing came when I bumped into him last summer, outside Anderson & Sheppard — where else? — on the corner of Savile Row. He said an announcement was imminent. Maybe more than one.

At Simpson’s, six months later, I wondered why, given he has already achieved so much, and the economics of hospitality remain so fraught, he would want to return?

“I felt there was a lot of unfinished business,” he says. “There are so many things I’d still like to do. I love the creative process. I would have loved to have created or composed or performed or written, but I never felt I would be good enough. I get some of that from restaurants. I want to do it. I enjoy it. There were lots of opportunities, but I waited for the right one.”

First announcement: The Park, a “21st-century grand café” serving modern European cuisine on the corner of Queensway and Bayswater Road, opposite Kensington Palace Gardens. It’s on the ground floor of a brand-new building housing ultra-high end apartments. His email to customers announcing it: “Oh, how I have missed you.”

“It’s really exciting,” he says. “Because I’ve spent so much time doing early 20th-century grand cafés, the idea of doing an early 21st-century grand café was very exciting. I could see it straight away, design wise. I thought, that’s all very well, but you can’t do schnitzel and chicken soup, so what’s it to be? At the time, I was stumped.”

The name came first. “The Park. Sounds quite American. Hmm. That becomes interesting because the equivalent of the grand café in America, really, was the diner. So there’s this merest hint of it being an interesting diner. Then that made me think about that big Californian, Italian-style movement of the 1970s and into the 1980s.” He mentions Jeremiah Tower and Alice Waters of Chez Panisse in Berkeley; Jonathan Waxman and Michael McCarty of Michael’s in Santa Monica.

“I thought about how that moved to New York and I thought if the New York restaurateurs had this space on Central Park what would they do? And then I could start to see it: an all-day offer, slightly brunchy, the sort of place where somebody could come in sports clothes with their dog during the day, and then in the evening they could dress up if they wanted. For me, I absolutely love going to a place where a restaurateur is not greedy and instead of putting four tables in, putting three tables in with banquette seating where you have corners. The Park will have 30 corners and booths, so a lot of really comfy tables. And simple, good, ingredient-led food. It’s very much going to be grill-led. Seafood and salads. Comfort food in that American idiom.”

Then the cheering news that King would return to the location of his first success to open a restaurant called Arlington, on the site of the old Caprice. He can’t call it Le Caprice because Richard Caring, who closed it in 2020, still owns that name. (He did ask. Caring demurred.)

I suggest that it’s a dangerous game, returning to the scene of former glories. Scott Fitzgerald said that you can’t repeat the past. “That was always my fear. There’s hardly a meeting goes by when I don’t remind the team we’re not replicating the old Caprice. You say Scott Fitzgerald, I would say Lampedusa, The Leopard. Prince Tancredi, answering the question of why things have to change. He says for things to remain the same, everything must change. But you don’t change the ethics, you don’t change the fundamental aspects of it.”

When people walk into Arlington, he hopes, they will think, “Oh, good, it’s the same.”

“And yes, you will get crispy duck salad and salmon fishcakes and bang bang chicken. But there will also be new dishes, and each of those dishes will also be looked at and we’ll ask, ‘Could we do it better?’” And if they can’t, they won’t. “If you order a salade niçoise, a lot of modern chefs will grill tuna to put on top of the salad. Actually, you want tinned tuna. You have to be careful that you’re not changing for changing’s sake. I think there will be a lot of nostalgia there.” Jesus Adorno is back, too.

Finally, Simpson’s. It had its last makeover in 2017 but closed in 2020, like Le Caprice a victim of the pandemic. King calls it “London’s last grande-dame restaurant”. Simpson’s first opened in 1828 and was famous for its roasts, carved tableside from trolleys. I poked around while waiting for King to arrive. There were the trolleys, arranged haphazardly in a corner of an otherwise empty room, waiting to be redeployed.

Arlington officially opens for business next week. If everything goes to plan, The Park will open at the end of May, and Simpson’s at the end of September.

“Ambience is that intangible thing that cannot be defined,” says Richard, the Jeremy King-like restaurant manager in Harold Pinter’s play.

This is pretty much what King says to me when I ask him to identify the secret sauce that elevated Le Caprice and The Ivy and The Wolseley and the rest so far above all the other contenders. And that will distinguish Arlington and The Park and the new Simpson’s.

He also says this. “There’s a difference between a restaurateur and a restaurant owner. The difference is that restaurateurs do it from the floor and restaurant owners do it from the boardroom. And I think that makes a massive impact on the customer experience. It’s about heart and soul, which make a restaurant special.”

He talks about a recent London opening that has captivated critics and customers: The Devonshire, a pub and grill room in Soho, and its owner-operators, Oisin Rogers and Charlie Carroll, and chef Ashley Palmer-Watts.

“If you look at it, at the design and so on: nothing to it really. But it has caught the imagination. And I think that’s because of the spirit that runs through it. And I think we under-estimate how important that feeling is.”

He likes that The Devonshire’s decor is understated. “It plays into my assertion that great design should never shout for attention but should withstand scrutiny. I think a lot of restaurants nowadays are done to attract attention, and I think they leave a fairly shallow experience. When we look at some of our most enjoyable experiences in restaurants, they’ve often been very simple places. Often abroad, maybe by a beach or down a back street, but there’s just been something magical which transcends. And I think the human presence [of the owners] makes all the difference.”

Recently, he had dinner with Ruthie Rogers on a Saturday night at The River Café. He was there first and watched her arrival. “So many tables just lit up when she came into the room and said hello. Restaurateurs make the mistake often of feeling they have to entertain the customers. I feel very strongly that certain people might want that, but generally people just want to feel secure, and feel loved.

“Robots,” he continues, “can do all the things front of house staff can do, but they have no intuition, no instinct, they can’t love, there’s no empathy; all the things we can bring. And the trouble is, in so many restaurants nowadays humans are not using their human capabilities.

“I’ve been thinking about it a lot,” he says, “with the new restaurants. How do we do that? In a way, it’s about trusting the staff, giving them a bit more self-determination. Which is hard because I’ve built restaurants over the years on strict discipline. My next phase will be different. Unless the staff believe in it, and are happy, they’re not going to give the customers a good time.”

It all comes back to the French thing. To conviviality. To emotion. To panache.