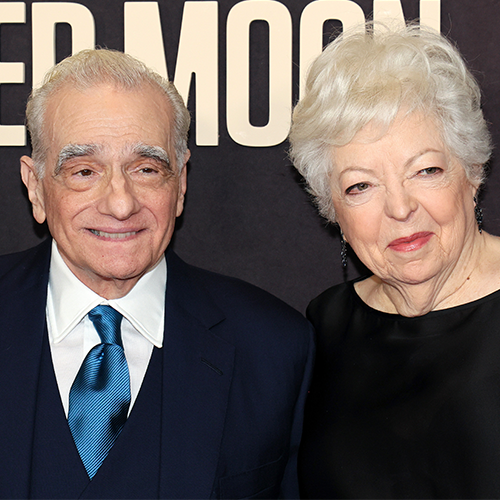

It’s been a big week for Thelma Schoonmaker. Killers of the Flower Moon, the great film editor’s 22nd feature collaboration with Martin Scorsese, has been packing in great reviews and great audiences in the days preceding our meeting at the British Film Institute’s central London offices.

“Oh, it's been a joy!” exclaims this hale and hearty 83-year-old triple Oscar-winner. “Because it's a very unusual movie. We wanted to help open the eyes of America to what we did to the Indian nations. We took everything away from them.” Responses to pre-release viewings – notably screenings held for members of the Osage Nation whose ancestors were murdered en masse by white oil barons in 1920s Oklahoma – were positive. “But we didn't know, when it got out there, what was going to happen. But the word of mouth is incredibly strong… So even though it's an unusual film and a real commitment, when you go to see it, it's working.”

That “real commitment” speaks in part to the film’s length. At 206 minutes, it’s the director’s second longest movie. The longest? His last one, 2019 mob epic The Irishman, which clocked in at 209 minutes. As he’s gotten older, so Scorsese, 81 this month, has gone deeper, further, more operatic. But when a movie nudges the three-and-a-half hour mark, is that a fundamentally grander task for the craftsperson tasked with literally cutting it together?

“No,” Schoonmaker replies breezily, literally waving away the suggestion. “It might take a little longer, but not really. With our movies, we do rough cuts – sometimes as many as 12.” Those cuts-in-progress are screened for people in she and Scorsese’s New York and Hollywood inner circles. “Then we start opening up to people we don't know. Then we go to bigger audiences. And we learn from what we're hearing, and then we do another cut. Then we screen again, and then we do another... We're very lucky. A lot of editors aren’t given that kind of time, which I think they should be.”

Because of the American actors’ strike, she and Scorsese, the director in particular, have found themselves doing much of the PR heavy lifting for Killers of the Flower Moon – “publicity that normally would be being done by Leo and Lily and Bob,” she says of the films three towering leads: serial Scorsese collaborators Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert De Niro, and relative newcomer Lily Gladstone.

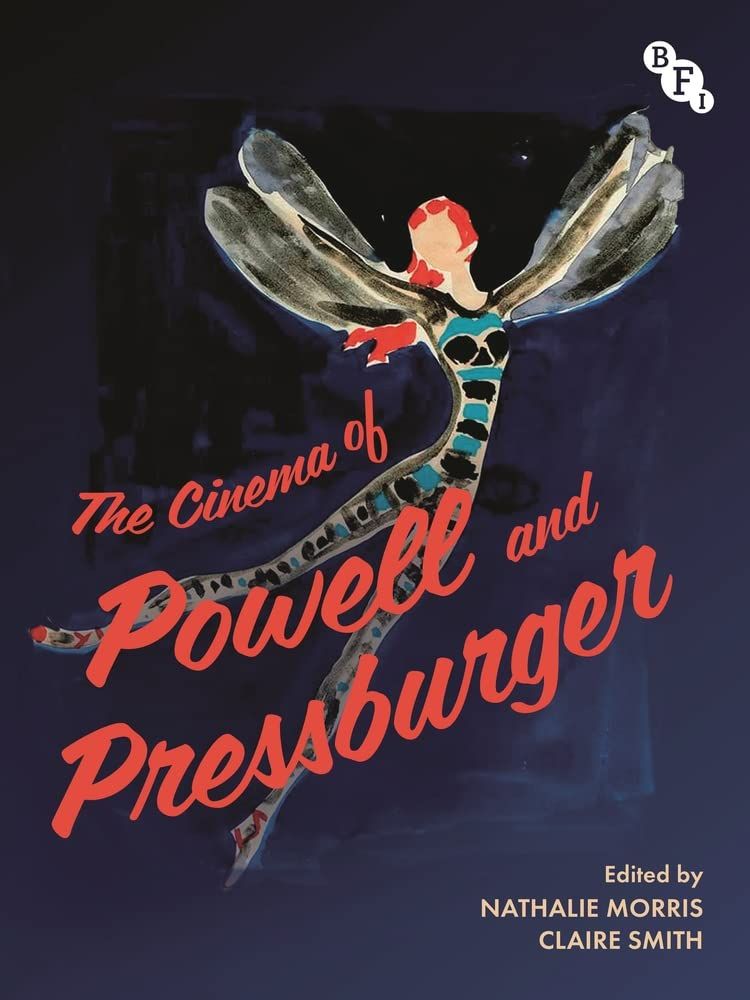

But the main focus of Schoonmaker’s promotional push in the UK this autumn is the launch of a major 12-week season staged by the BFI – Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell + Pressburger. She and Scorsese are longstanding cineaste curators – and financiers – of the legacy of the great mid-20th-century British filmmaking duo of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Collectively known as The Archers, the name of their production company, the Englishman and Hungarian émigré were visionary creators of two-dozen films, not least their three, back-to-back, post-war, Technicolor masterpieces, A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948).

“Marty says The Red Shoes in his DNA,” notes Schoonmaker of a cinematic treasure that includes at its heart a hallowed, 17-minute, magical realist ballet. It’s a film that she first saw aged 12 while living on the Caribbean island of Aruba, in an “American colony” created by Standard Oil. Returning to the US aged 15, she tuned into a “wonderful TV show called Million Dollar Movie, where they ran one film nine times a week.” She later learned of another avid viewer. “Marty would [try to] watch a Powell and Pressburger movie [all] nine times unless his mother said: ‘If you don't turn that off, I'm going to start screaming.’ But there were all these Powell and Pressburger films that Marty and [Francis Ford] Coppola and [Steven] Spielberg saw – much more so than people here [in the UK].”

That’s because, with the rise of realism in British cinema – “kitchen sink dramas” such as Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) and This Sporting Life (1963) – the films of Powell and Pressburger fell out of fashion in the UK. They were viewed as conservative, colonial, old-fashioned. As Pressburger’s filmmaking grandsons, Andrew and Kevin Macdonald, noted in a joint statement ahead of the launch of the BFI’s programme, “the Powell/Pressburger canon was almost entirely ignored, even reviled, during the 1960s and ’70s”.

But for many their legacy burned brightly, and this blockbuster season is the boldest step yet in the rehabilitation and re-appreciation of their work.

“You Archers: your pirate soul on the high seas cinema is everlastingly buoyant,” writes Tilda Swinton in an accompanying book, The Cinema of Powell and Pressburger. “Consistently referred to as perhaps the most quintessentially English of filmmaking families, we nonetheless recognise as unmistakably essential to your universe a peerless production design born of the luxurious glamour of continental European expressionism, the smoke and mirrors of the theatre, the opera and the mark of the hand painted, hand wrought, hand made.”

All that, and a legendary cinema psychopath, too. The BFI season – which encompasses a new documentary, accompanying exhibitions and screenings of freshly restored prints, their makeover overseen by Schoonmaker – also includes Powell’s solo work. Key in that canon is the director’s transgressive horror from 1960, Peeping Tom. It’s back in cinemas on the day of my interview with Schoonmaker. Given that the American was married to Powell, who died in 1990, for the last decade of his life, it’s an especially poignant moment. Not least because Peeping Tom is popularly viewed as having killed the filmmaker’s career.

Not quite, says Schoonmaker.

“That's a little overstated because he did make five films after that.” But, yes, the critics “devastated” a film about a murderer who films his dying female victims’ terror, then edits the footage into a snuff movie. “Michael put in compassion for [the character of] Mark, who has been tortured by his father as a child and is unable to control what he's doing. Michael wanted people to understand that. The critics felt guilty for feeling compassion for a serial killer. It freaked them out. They couldn't just accept it as great art.”

The critics, she continues, “felt the public shouldn't see it. And if they approved of it, they would be implicit in having people feel sympathy for this man. So unfortunately, the studio pulled the film immediately. It was a terrible blow to Michael’s filmmaking career.”

The film vanished, a lost folly. But across the ’70s its reputation grew, as did the reputation of the young cinematic disruptor who was Powell and Pressburger’s biggest American champion. Scorsese first, in 1975, tracked down a penurious Powell in his Cotswolds cottage – there, Schoonmaker describes the half-forgotten filmmaker as “chopping wood because he couldn't afford fuel. Couldn't buy a bottle of whiskey for a year or more. It was a terrible time.”

But over lunch, Scorsese – who made Taxi Driver that same year – peppered the elderly director with questions about his approach, his technique, his groundbreaking use of special effects. “And Michael said ‘the blood started to run in my veins again,’” recalls his widow. “That's how devastating what he went through was.”

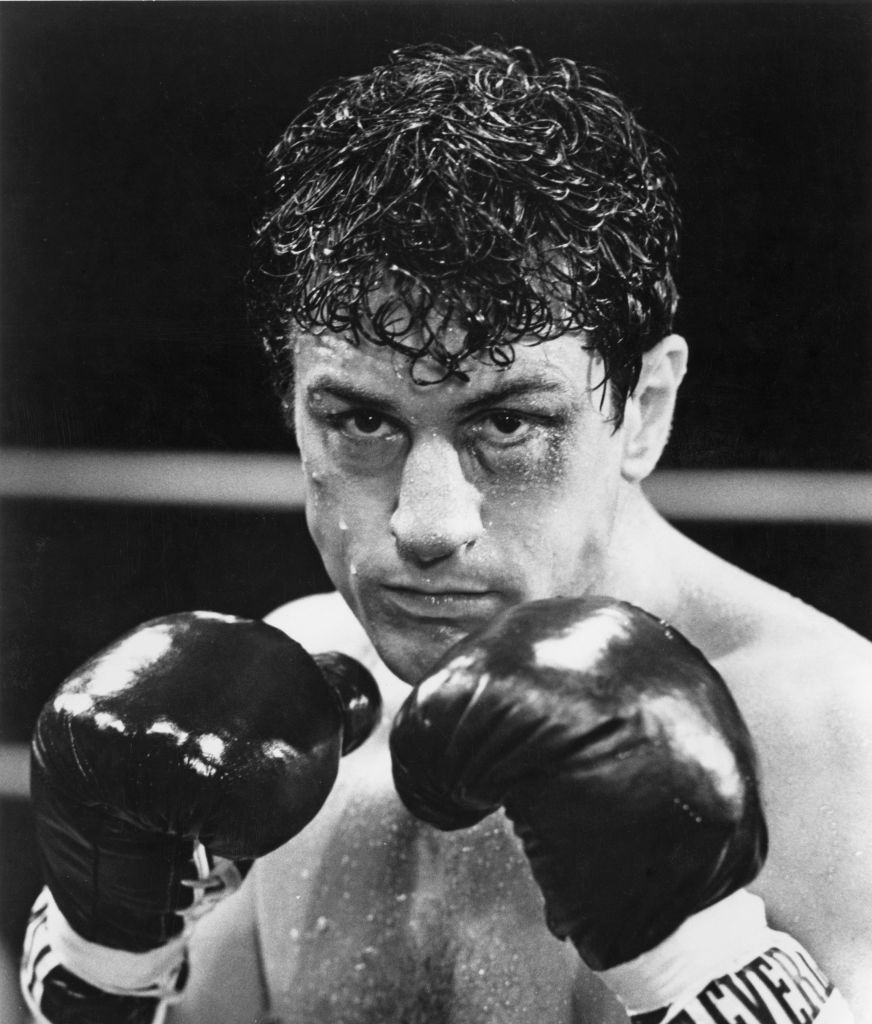

Scorsese followed through on his fanboy enthusiasm, and then some. In 1979 he arranged for Peeping Tom to be shown at that year’s New York Film Festival, and then paid for its redistribution in US cinemas. To mark the moment, Scorsese held a dinner in New York in Powell’s honour. He invited along the editor he’d hired to cut his latest movie, Raging Bull, a boxing biopic he'd shot in black and white, partly on the advice of Powell.

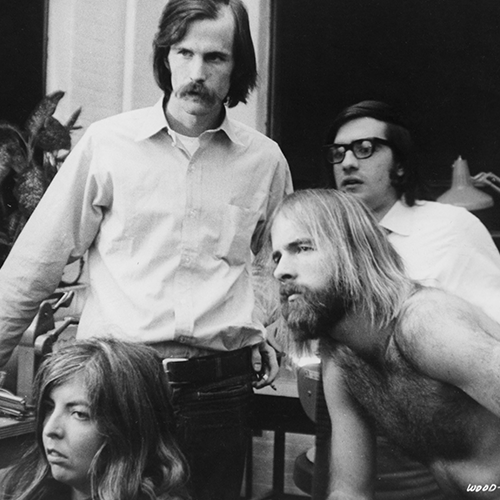

“I was just so struck by Michael,” recalls Schoonmaker, who had last worked with Scorsese on his debut feature, 1967’s Who’s That Knocking at My Door. “He was so extraordinary. He came back to talk to me – I was editing Raging Bull in a bedroom, and we had film racks in the bathtub.”

When Powell saw this domestically mundane version of an editing suite for a punchy, monochrome masterpiece, “he burst into laughter. He thought that was the funniest thing he'd ever seen.”

A friendship was born. Then, in early 1981, Scorsese and Schoonmaker were in Los Angeles for the Oscars, where Raging Bull was up for eight awards – it would win two, one for De Niro (Best Actor) and one for Schoonmaker. By then Powell was also in LA, working in script development at Francis Ford Coppola’s ill-fated Zoetrope Studios. “We started having lunch. Then things went on to dinner!” A romance blossomed, “much to the surprise of everybody”, because Powell was over three decades her senior. “But he had the heart of a 16-year-old.”

They married in 1984, when she was 44 and he was 78, and she describes Powell as an energising force coming into her life. “He was in very good physical shape then, still.” All told, “we had the 10 happiest years of my life together. So Marty gave me the best job in the world and the best husband in the world!”

That professional union has remained staunch, with Schoonmaker barely working for anyone other than Scorsese and the director only using Schoonmaker. Ask her how their partnership has changed over the course of their stellar, history-making collaboration, and Schoonmaker is typically modest.

Firstly, she downplays the growing fandom surrounding her work. “It's overdone because Marty and I do it together. I'm constantly trying to make people understand: it's not just me,” she says, rapping the table insistently. “Plus, like Michael did, Marty has an incredible sense of editing.”

Secondly, she credits that sense with getting her where she is now, at the top of her profession.

“At first I didn't know anything about editing. Marty taught me everything, particularly on Raging Bull. Now it's become more of a real collaboration… But he felt he could trust me to do what's right for the movie. And there wouldn't be ego battles – which there are a lot in film editing rooms, between the director and the editor. It was never that way with us. That's how our relationship grew. And then, of course, we share this great love of Powell and Pressburger.”

Which was their toughest film to make? Schoonmaker thinks for a moment before plumping for The Departed (2006) – in the edit the pair struggled with the opening montage. “Each film has a different problem,” she says. “Maybe it's a problem of length, or it's a problem of how much do you want to explain. Michael said to Marty and me: ‘Never explain. Always know that your audience is ahead of you. You try and stay ahead of them. And let them figure it out.’” Scorsese has stuck with that credo. “Marty hates it when he sees a movie where they're telling you what to think. He wants you to engage with the movie in the same way that Michael did.”

The irony with The Departed is that it’s the only film for which director and editor both won Oscars. It was Schoonmaker’s third (she also won for 2004’s The Aviator), a record for a female editor. Scorsese still hasn’t won a second.

“Yeah, we're not very lucky with the Oscars. I mean, Marty has deserved many.”

“You’re luckier than he is,” I say.

“I know, and that's not fair. Because they're really his as well as mine. But Marty should have won at least seven, as far as I'm concerned. But we're very unlucky at the Oscars," she repeats, "because the films are sometimes very unusual. And people are sometimes not used to it, or they resist it, or [resist] voting for it.

“I think he would have liked to win for Raging Bull,” she adds. “When we were standing there, those of us who did win, I was waiting for Marty to come with his Oscar. And he didn't. It was the worst night of my life. It was devastating that he didn't win. A movie like that, that is so brilliantly directed. But it was a tough movie. And Ordinary People, I understand it's a very good movie, I've never seen it,” she says of the Robert Redford weepie which trumped Raging Bull to win Best Picture and Best Director. “But people were maybe a bit put off by the toughness of Raging Bull. But look how it's lasted. It's a benchmark movie.”

Killers of the Flower Moon is another of those. It’s surely a shoo-in for multiple Academy Award nominations, as is the season’s other intelligent blockbuster, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer – also edited by a woman, Jennifer Lame. Schoonmaker hasn’t seen that film either, so has no comment on the suggestion that the two frontrunners for editing Oscars will be women. “Yeah, well, we'll see what happens, ha ha!”

But she will say that “there’s tonnes of women editors now... But there were lots [historically]. During World War One, there were so many men at war, and women were in the labs, rolling the film, the negatives and everything. And when D.W. Griffith and Sergei Eisenstein started [filmmaking], they needed women to splice the two shots together. And what developed was something called editing, and the role of an editor, which hadn't existed before.

“But then when men came back from the War, they took it away from the women. Because it became a good paying job. But Anne Bauchens was nominated for an Oscar for a very early Cecil B. DeMille,” she says of 1934’s Cleopatra. “So they were around. But not like it is today. It's amazing.”

What, then, is Thelma Schoonmaker’s view of her own legacy?

“My own legacy?” this remarkable, game-changing giant of cinema shoots back, slightly incredulous at the very thought. “Oh, no, it's really Marty's legacy that I'm part of. But when Michael died, he left a little furnace inside of me, burning to preserve his legacy. And Marty and I share that. No one has done more for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger than Martin Scorsese. So we share the movies, and we share this legacy. And it's a beautiful thing.”

Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell + Pressburger runs until 31st December