When the screenwriter Russell T Davies announced he was leaving Doctor Who, the show he resurrected for the BBC in 2005 with unprecedented global success, to concentrate on telling gay stories, he meant it. In 2015, his drama Cucumber broke ground with its portrayal of the turbulence of gay relationships in middle age. It was accompanied by two interconnected series: Banana, an anthology show focusing on the LGBTQ community and Tofu, a documentary series about modern sex culture (“cum-in-your-face frank” — the Guardian.) All three were named for different states of tumescence.

In 2018, Davies wrote A Very English Scandal, the hit mini-series based on the book of the same name, concerning the Jeremy Thorpe scandal of the 1970s, with Hugh Grant playing the disgraced Liberal Party leader and Ben Whishaw as his lover, Norman Josiffe. That was followed last year by Years and Years, the dystopian sci-fi drama following a Manchester family through 15 years of future political and social turmoil that now appears to have been written with the aid of a crystal ball (monkey ’flu pandemic; BBC shuts down; populism turns out to be A Very Bad Idea) and whose lead character, Russell Tovey’s Daniel Lyons, is obsessively in love with a man. It is true that this run was broken in 2016 by Davies tackling Shakespeare, but happily his vision for A Midsummer Night’s Dream included Hippolyta snogging Titania, show tunes, fireworks and Matt Lucas’s Bottom.

“The gayest version of Shakespeare for BBC1 you’ve ever seen!” booms its creator, when we meet one morning in a London hotel. Davies divides his time between his native Swansea and his adopted Manchester, cities that have been as important in his dramas as any human character (or robot, alien, giant telepathic head in a jar etc). He is here to talk about his new show, which was called Boys until an 11th-hour rebrand to It’s a Sin — the former being, according to Davies’ PR, “only a working title” and according to Davies’ Instagram “we changed the name from Boys because of The Boys on Amazon. Also, Google ‘boys’ and it can lead you to some terrible places …”

Whatever the reason for the name change, this series is his masterpiece: a drama as likely to emblazon itself on the national consciousness as his breakout show about the loves and lives of a trio of young men in Manchester’s gay village, Queer as Folk, did two decades ago.

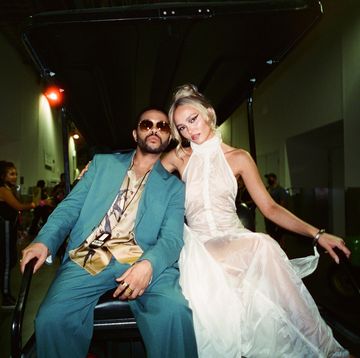

Set in 1981 on the cusp of the Aids epidemic, It’s a Sin follows five 18-year-olds who leave home and move into a flat in London (“the Pink Palace”). In five parts, it follows their lives over the next decade, with particular focus on the impact of HIV/Aids. The knockout ensemble cast is led by Olly Alexander, singer with the band Years & Years and LGBTQ advocate. It is everything you’d expect from an RTD drama — witty, political, poignant, clever, camp and significant — but with a new heft and authority.

Towards the finale there’s a left turn that made me shout “No!” at the telly: a two-move checkmate by a master storyteller. “I was there,” Davies says. “I was 18 in 1981, so I’ve been wanting to tell this story for that long, really. When the idea for Queer as Folk cropped up in 1988, it’s interesting that I didn’t write this, because I could have. But we were still mid-trauma and I can only presume, in hindsight, that I was just too close to that.” And perhaps, he reasons, there were other factors.

“I like writing stuff that no one else has written, I like to go into new territory and this isn’t new territory, lots of brilliant minds have written brilliant dramas, documentaries and polemics about this. I’m very much aware of joining a body of work. Finding things that hadn’t been said, finding my take on things took a long time. It’s an unusual series. It doesn’t have any heroes. In some ways, it doesn’t have any plot. It’s a story about the passing of time. I mean, it’s full of mishaps and adventures. It’s full of laughs, it’s full of tragedy — obviously — but actually all that happens is 10 years pass. To be honest, you’ve got to have a lot of confidence about that. If I was a 21-year-old writer I would have had doctors battling to save every man.”

One of the things that may be entirely new territory is the portrayal of everyday homophobia. Applying for a mortgage, one character is asked if he’s ever shared a bed with another man. Another, filling out a form in a hospital, is asked if he’s ever slept with animals. Another, joining a school as a supply teacher, is shown around by a colleague with a throwaway, “We know what you’re like, you lot”, before being dispatched to the library to root out any books with gay characters: “Perfect job for you.”

Outdated social mores are usually played for laughs in period drama — the racist dad! “It were a different time” et cetera — here it’s an insidious feature of day-to-day life.

“That’s a real thing,” Davies says. “I didn’t make that up. That was an estate agent’s question, ‘Are you homosexual?’ Also, ‘Have you ever shared a bed with a man?’ I went through that. I just denied it all. Got my mortgage. Still here. Still got a roof over my head.”

Good too is the denial of the disease — from the boys’ parents, of course, but also the boys themselves.

“They say it affects homosexuals, Haitians and haemophiliacs,” Olly Alexander’s character, Ritchie, says to camera. “Like there’s a disease which just targets the letter ‘h’. Who’s it going to get next? People from Hartlepool?”

It’s virtually impossible to imagine the tabloid rumpus that greeted Queer as Folk — originally Queer as Fuck — happening now. Indeed, you’d hope some progress had been made in the last 21 years. Olly Alexander is a hero to LGBTQ audiences as well as a mainstream pop star, while young people today are well versed in gender politics and rather broader-minded than those of the Britpop era.

Actually, Davies says, back then it wasn’t just the tabloids who were appalled at the prospect of men having it off on TV.

“We remember the outrage being ‘tabloids: bad, common sense: good’,” he says. “But the press launch was ferociously hostile. Two hundred journalists! You never get 200 journalists to anything… The biggest attacks were actually from the gay press because we didn’t show the characters having safe sex. They were having safe sex, obviously, because they were sensible men, living in the world. But because we didn’t show a condom we massively failed the gay community.”

It did famously show rimming, however — new territory for TV, in more ways than one.

“It was important, that rimming!” Davies says. “It was very important to show a sexual

act that [15-year-old character, played by Charlie Hunnam] Nathan Maloney had never even imagined, that was literally an eye-opener for him.” He roars. “It’s me getting down to the physical. I didn’t do it to shock.”

A new bum-related TV taboo is shattered in It’s a Sin. And, to be fair, it wouldn’t be much of a show about young people and Aids if it skirted the sex.

“That’s how it’s transmitted,” Davies reasons. “And that whole relationship with sex is why it was so silent because people didn’t talk about it. Coronavirus wouldn’t be as talked about if it was transmitted intimately because we wouldn’t feel free to talk to our children about it — wrongly. So, you have to get down to that physical level. Which I like doing anyway, let’s be honest. It’s not something I’ve shied away from.”

Given the show’s impossibly gloomy subject matter and the requirement to turn it into entertainment, wasn’t the tone a challenge?

“Yes, that was hard,” he says. “In order for people to watch it you want to cast good, big, sexy people and then you want the drama to be lively and to be fun and to reach out to people. You’re not coming along for a misery-fest. Even though when it’s miserable, it’s marvellous! But it was hard to pitch to people because it’s a series about young boys dying.”

In 2011, Davies’ boyfriend, later husband, Andrew Smith was diagnosed with a brain tumour and Davies, working in the US at the time, moved back to the UK, becoming his primary carer until his death in 2018. Understandably, it informed the writing for It’s a Sin. It’s beholden on him to portray grief honestly, he says. And his late husband will be in “every good man” he writes now.

It’s a Sin did the rounds of commissioning editors before it ended up being made for Channel 4 — who’d originally rejected it. “Look, no one’s in a rush to give away money,” Davies says. “And I know I have an easier time than most, but if an hour of drama costs a million quid, no one wants to give away five million quid.”

What about the streaming services? Surely Amazon and Netflix have come courting.

“Not particularly,” he says. “I’m a little bit sad that I’m too old for the gold rush. But then I was doing the gold rush in the 2000s, when I took that Doctor Who empire and span it off into Torchwood and The Sarah Jane Adventures, with vast online resources, an animated Doctor Who…”

At one point he was writing for and running six Doctor Who-related shows at once, plus holiday specials, books, exhibitions et cetera — an insane workload. (He’s still a workaholic, as the 4am social media posts from his writing desk confirm.) “I was 10 years too soon! That would be its own channel now.”

In 2009, the show’s success led to him, plus commissioner Jane Tranter and producer Julie Gardner, being posted to Los Angeles to work for BBC Worldwide (Tranter and Gardner subsequently established the production company Bad Wolf, which in the last four years has been behind The Night Of, His Dark Materials and I Hate Suzie; not bad going). “Those Netflix contracts are rare,” he says. “Oh, what I’m saying is… no one’s fucking offered me one! Give me a rail — that’s what they call them — on a channel. You could have my medical drama, my historical drama, my modern drama. I’d be away! I look at Ryan Murphy [Glee screenwriter with an absurd amount of shows on the go, and a so-called

Netflix “mega-deal”] and I envy that freedom.”

Actually, he says what he’d really like to develop is a gay superhero. (Davies initially wanted to be a comic book artist.)

“The Disney monolith, the vast, outer space, superhero myth, is very white, very straight,” he says. “Avengers Endgame, one boring gay man gets one line and that’s all we’re reduced to. It always fascinates me, those superheroes: the women have huge breasts and the men have flat groins. It’s the most repressed sexuality of all, superheroes. The sexiest men, practically naked and sexless. Fascinating! It’s the groin. I could write a history of the groin. Give me a gay superhero! I would have a whale of a time. It wouldn’t even be offensive. I don’t mean they’d be fucking all over the place…”

The Netflix model, he says, “is going to collapse sooner or later”. As for the BBC, the key word is “sooner”.

“It’s simply going to be defunded, and it is going to be destroyed. That’s a fact. It’s got, what? Seven years to go? I’ve fought enough for it. I give up now. The opposition to it is so vast.”

His energy is better spent on representational casting, something he has pursued doggedly throughout his career. (His Doctor Who featured pensioners and toddlers, a “pan-sexual” lead, a character with spina bifida and more regional accents than Corley motorway services.) His bugbear today is “Welshface”.

“English actors putting on Welsh accents,” he explains. “That’s got to come to a halt. I’ve started to write to broadcasters about that. I’ve really had enough.”

Davies is a big chap with a big laugh, his characters so full of life, his anecdotes prefaced with “I’ve been so lucky…” and signed off with “…what an amazing thing to have done”, that I mention he’s an optimist, a glass-half-full man. (Even on his deathbed, one It’s a Sin character says: “I had so much fun.”)

In fact, he says, the opposite is true. “I have a laugh and I’m a nice, lively bloke, I think, but the awful thing about the rise of populism is that none of it surprises me. I was brought up by two classics teachers, the house was full of the books of Roman and Greek myths, so the one thing I learned when I was about six years old, was that civilisations fall.

“I know I write optimistic dramas, but that’s because I’m a pessimistic person,” he says — then hoots with laughter.

When actor Christopher Eccleston was charged with bringing The Doctor back in 2005, he based many of his characteristics on Davies himself, notably his habit of saying, “Isn’t it fantastic?” — a phrase Davies repeats often today.

The central message of the show, Eccleston reasoned, was life is brief. Enjoy it.

It’s a Sin airs on Channel 4 in January

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts