“I have only good news,” beams the chef Nicklas Ekstedt, bounding excitedly down an icy slope to the edge of Källtorpssjön, a lake in the forested suburbs of Stockholm. It is a bright, quick morning in mid-February and winter still has its grip on the water. “We can get into the sauna straight away!”

“And it’s mixed day,” he adds, as a polite warning to British visitors, “so men and women in the same sauna. No clothes allowed.”

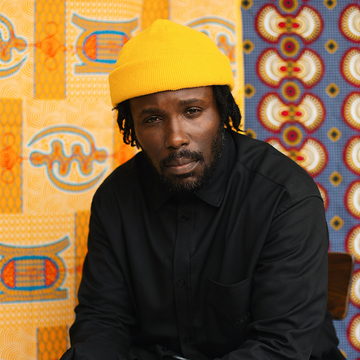

Ekstedt, 44, is a Swedish national treasure, in part for his championing of Nordic cuisine, his growing restaurant empire, and his mastery of open-fire cookery. But also, surely, for his easy charm, rugged good looks, and embodiment of a very Scandinavian vein of gung-ho. He feeds and he forages; he hosts TV shows, takes business calls while ice-skating and drives a Volvo SUV.

Earlier this year, Ekstedt, his flagship contemporary fine-dining restaurant in the city, which received its first Michelin star in 2013, underwent a massive refurbishment that expanded the dining room and broadened the kitchen. It is the reason for Esquire’s visit, and the reason why, today, we are huddled sweatily on the sauna’s terraced benching, unsure why clothing is verboten but towels are OK. Meanwhile Ekstedt gabbles animatedly with various fellow sweatsmen, who address him with a subtle, almost reluctant reverence, like fathers at a local rugby club chatting to a visiting professional, only nakeder.

Born in the rural resort village of Järpen, seven hours north of Stockholm, Ekstedt struggled at school, but found cooking via his parents, who were grocers in the city when they met. “[They] were pleasantly surprised when my culinary teacher praised my progress,” he remembers, noting that he was flagging in most other subjects. “From the age of 17 onwards, I became completely consumed by the culinary world. I ordered books, traveled, and immersed myself in conversations focused on food.”

While he was learning to cook, he wanted to get as far away from Järpen as soon as possible, and as he diversified his experience in kitchens across Europe, including El Bulli in Spain and The Fat Duck in the UK, that sentiment was reflected back at him. “People showed little interest in learning about my home country, its cuisine, or the ingredients I was familiar with,” he remembers. “It seemed as though Sweden held no interest to them.”

When Ekstedt opened his first restaurant in the southern city of Helsingborg, aged just 21, it made little attempt to align with the locale (or as he somewhat wryly puts it on his website: “The focus was on ultratrendy molecular gastronomy, serving dishes such as asparagus cloud and deep-fried rice paper”). A decade or so later, with further restaurant openings under his belt and an established TV career, Ekstedt hit something of a wall; then one afternoon while at his summer house in the Stockholm archipelago, he cut down a birch to fuel a fire pit, just as he’d done as a child, and the proverbial lightning bolt struck. In 2011, in Stockholm, he opened Ekstedt, which pays homage to the food and traditions of Scandinavia, in which the kitchen’s only source of heat is fire.

The afternoon before the sauna, Ekstedt offers a tour around the snowbound centre of Stockholm, pointing out quirks of the royal palace and divulging tidbits of historical intrigue. (Did we know that handsome, highly decorated Napoleonic soldier Jean-Baptiste-Jules Bernadotte was unexpectedly made crown prince of Sweden in 1810, and became king eight years later? We did not!)

We stop in at the bijou restaurant Bakfickan to warm ourselves with rösti and dry white wine, then a drink at Ekstedt’s new natural wine bar, Tyge & Sessil. Ekstedt opened Ekstedt at the Yard at the Great Scotland Yard Hotel in London a couple of years ago, and has clearly been influenced by the trendier boroughs of the city, lifting the concept of “Hackney Tapas” (small plates), cloudy wine and tattooed (and lovely, knowledgeable) staff and plonking it down on Brahegatan.

From there it is but a few steps to Ekstedt and the seven-course tasting menu. Ekstedt in baggy cords and Etnies trainers, talks us through the menu. Squid is “hay-flamed”; reindeer “juniper-fired”, and wild oysters flambéed with a “flambadou”. If you don’t know what a flambadou is, you will never guess: a small cone of cast iron, with a hole at its tip, on a metre-long pole, is thrust into the fire until red hot, then filled with lard or tallow, which instantly ignites in a firework of flesh-scented flame. The molten fat is then drizzled over the oysters, lightly frying, and imbuing them with a subtle, fire-roasted flavour.

In a space that is all pale wood, white tiles and copper, we witness the flambadou at work, wielded by head chef Florencia Abella (diners have always been able to watch the chefs in action at Ekstedt, only now there’s more room to do so). The kitchen is focused on the Dickensian hearth, featuring an oven, stove top and open fire, which needs constant attention and hours of preparation every day. It is the old and the new intertwined: chefs in impeccable outfits wield tweezers and squeezy bottles as the fire crackles and pops in the corner. We taste fat, meaty scallops, dolloped with caviar and skewered onto popsicle sticks and gawp at the work Abella and her team do in such a snug setting. The food is mind boggling; delicate and rich and soulful and storied.

Stockholm is now one the best food cities in the world, thanks only in part to Ekstedt’s growing empire. There are currently nine spots with at least one Michelin-star – if that’s your barometer – and scores more beyond. Ekstedt recommends Petri on Kommendörsgatan, Babette on Roslagsgatan and Röda Huset, a cocktail bar focusing on – you’ve guessed it – Nordic ingredients. But Sweden’s own Nordic boom is dissipating. New chefs have been popping up in the city “like mushrooms”, he says. “People no longer limit themselves to being solely inspired by traditional Swedish cooking; instead, they draw inspiration from various cuisines around the world and blend them together. ”

Dinner finishes with a glass of Bute Mousserande Iscider. “Ice cider” is made with frozen apples, concentrating the sugar and making it more alcoholic, so it’s closer to a sparkling wine, and suitably moussey. Then a cocktail trolley arrives and things get a bit blurry. Ekstedt has long left us to our own devices, but we’ll see him in the morning after he’s done the school run. He mentioned something about a lake on the edge of town.

Ekstedt, Humlegårdsgatan 17, 114 46 Stockholm, Sweden, ekstedt.nu