Following the death of an innocent man at the hands of police in the USA, Britain is having a national conversation about the sanctity of statues of slave traders. It’s not that our chilly little island doesn’t have bigger issues of racism to confront, because it does. But for some reason, the symbolic destruction of the legacy of colonial oppression still somehow causes discomfort to a vision of Britishness that has never fully grappled with the realities of empire, or the micro-aggressions that our memories of it perpetuate.

When I’m not writing about statues on the internet, I’m a historian. I say this not to brag (if I wanted to do that, I’d make you call me ‘Doctor’), but because every time a statue gets pulled down in a country in the global north, someone makes the bad faith argument that we are "destroying history". We aren’t. When you went to school, you learned history from a book, or a computer, or a television. You did not learn it from a statue. Statues don’t educate, they celebrate.

I don’t recall many of these objections to statue-toppling when, as a teenager, I watched the 39ft figure of Saddam Hussein being in central Baghdad being pulled from its plinth by an advance unit of the US Marine Corps, which stepped in with an M88 armoured recovery vehicle to do the job that Iraqi hammers and fists couldn’t. Indeed Boris Johnson, engaging in full war reporter cosplay in post-war Baghdad, referred to that moment, and the looting that followed, by saying “In a word, it was democracy.” He even engaged in a spot of light looting himself. And yet 17 years and one month later, when the statue of 17th century slave trader Edward Colston was torn down in Bristol, Johnson’s opinion on statues and direct democracy was slightly different. “We have a democracy in this country. If you want to change the urban landscape, you can stand for election, or vote for someone who will.”

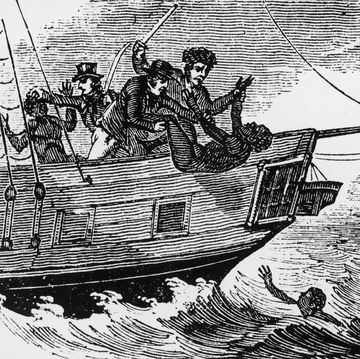

Johnson’s volte-face on pulling down statues isn’t rare. When that statue of Saddam Hussein came crashing down, it was almost universally acknowledged as a moment of liberation for the people of Iraq. Statues are symbolic: we use them to celebrate heroes. They literally and metaphorically tower over us. The statue of Edward Colston that was torn down in Bristol celebrated a man who stole 84,000 humans from Africa, imprisoned them, and transported them in such brutal conditions that as many as one quarter of them died and, often, were thrown in the sea, just like Colston’s statue. These slaves were traded for guns, which destabilised West Africa, leading to more war, more slavery, and more death. For British people of colour, walking past that statue is a daily reminder of the crimes of empire and the fact that their city – a city they had petitioned for years to remove the statue – refuses to acknowledge them.

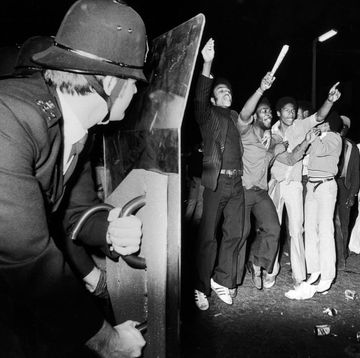

Racism is a legacy of empire, and it is far harder to toss away than a statue. George Floyd’s murder at the hands of Minneapolis police officers Derek Chauvin, J Alexander Kueng, Tou Thao and Thomas Lane has sent people into the street all over the world. The last time this many people were out in the streets of the global north was in 1968. Students in Paris ripped up cobblestones and built barricades; in Prague, people stood up to tanks with flowers; in Spain, they faced up to Francoism in the streets; in London, they fought riot police in front of the US embassy.

In Hamburg, German students pulled down a statue of Herman Von Wissmann, whose brutalities against the native population in German East Africa were not mentioned on his plaque. Those students had come of age after the second world war, they had never experienced colonialism, and they had grown tired of hearing their elders equivocate about the legacy of fascism and the sort of actions they were seeing in Vietnam on their televisions. So, the students, radicalised by boredom and cinematography, decided to move from conversation to action and in pulling down that statue, they forced Germany to confront the crimes of its recent, and distant, past.

We’ve largely absorbed the 1968 demonstrations into our cultural memory of the “swinging Sixties”, but the reality contained much less peace and love; the leader of that German movement, Rudi Dutschke, was shot by a right-wing activist who was inspired by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. After 1968, the world came to a new cultural consensus: racism wasn’t fixed, but it was forced to recede into institutions and hide behind legal codes and biases. Since then, we haven’t done very much to confront it. People like me have largely coalesced in this less-visible racism that gives us privilege, which we take for granted.

What we need to do now is not stop with statues and symbols – we need to do the work in our cultural memory and our history syllabi to make sure that we know why these statues aren’t OK, and why celebrating slavers is an affront to everything many of us claim to stand for. German students today learn about the crimes that were committed in the name of their nation. What German-ness means has changed since 1945, and this has occurred without a single statue of Hitler polluting Berlin’s streets, to act as a ‘reminder’. Even with the physical remnants of fascism gone after the war, it took public action to confront the crimes of the Nazi regime and the criminals who still held office in Germany. We must do the same.

Oddly, I find myself in agreement with Boris Johnson. Pulling a statue down is democracy. You don’t pull a statue down on your own, you don’t pull a statue down with a massive donation from a fossil fuel CEO. You pull down a statue when you come together with other people to take symbolic actions that need to be taken to begin a process of change.

When we tear down statues, we leave an empty space. In Hungary, where revolutionaries tore down a statue of Stalin in 1956, the plinth where he stood now just holds his boots. It doesn’t celebrate dictatorship; it celebrates the direct action that brave Hungarians took for democracy. Perhaps Bristol can do the same. Instead of coming to political agreement on how to replace statues, we can leave their absences as a monument to the power of people armed with a just cause and a decent grappling hook.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts

SUBSCRIBE