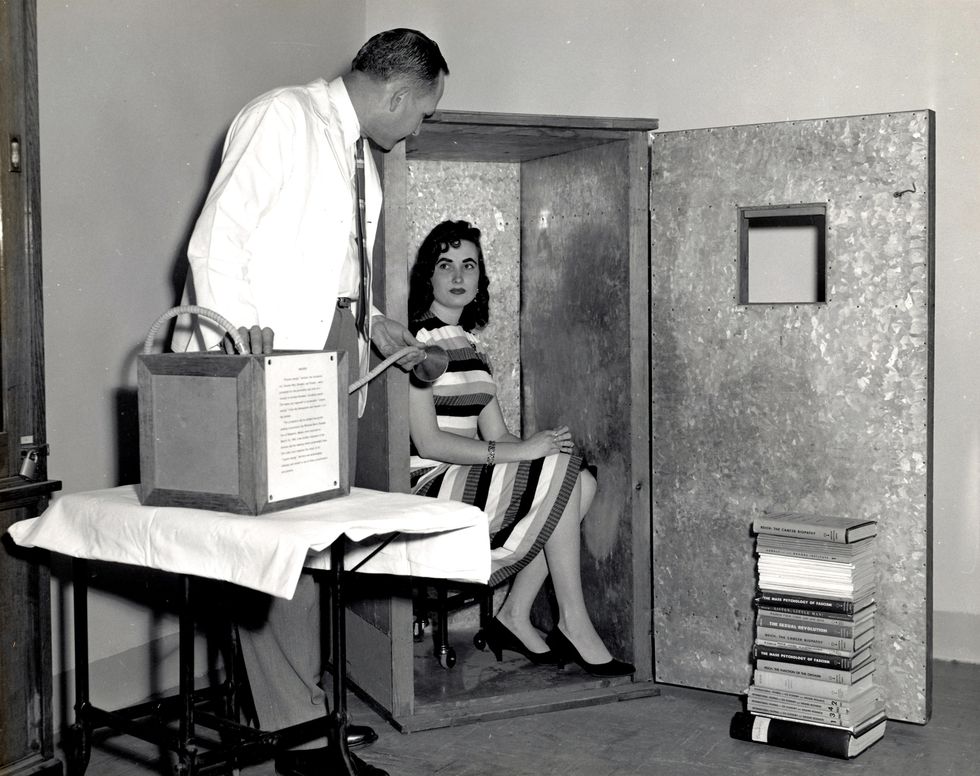

There’s a photograph of Kurt Cobain in a garden in Kansas in 1993, waving through a porthole, beaming, in what appears to be a one-person sauna. The rectangular cabinet he’s seated in, which belonged to William Burroughs, is an “orgone accumulator” — an invention of the renegade Marxist psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich.

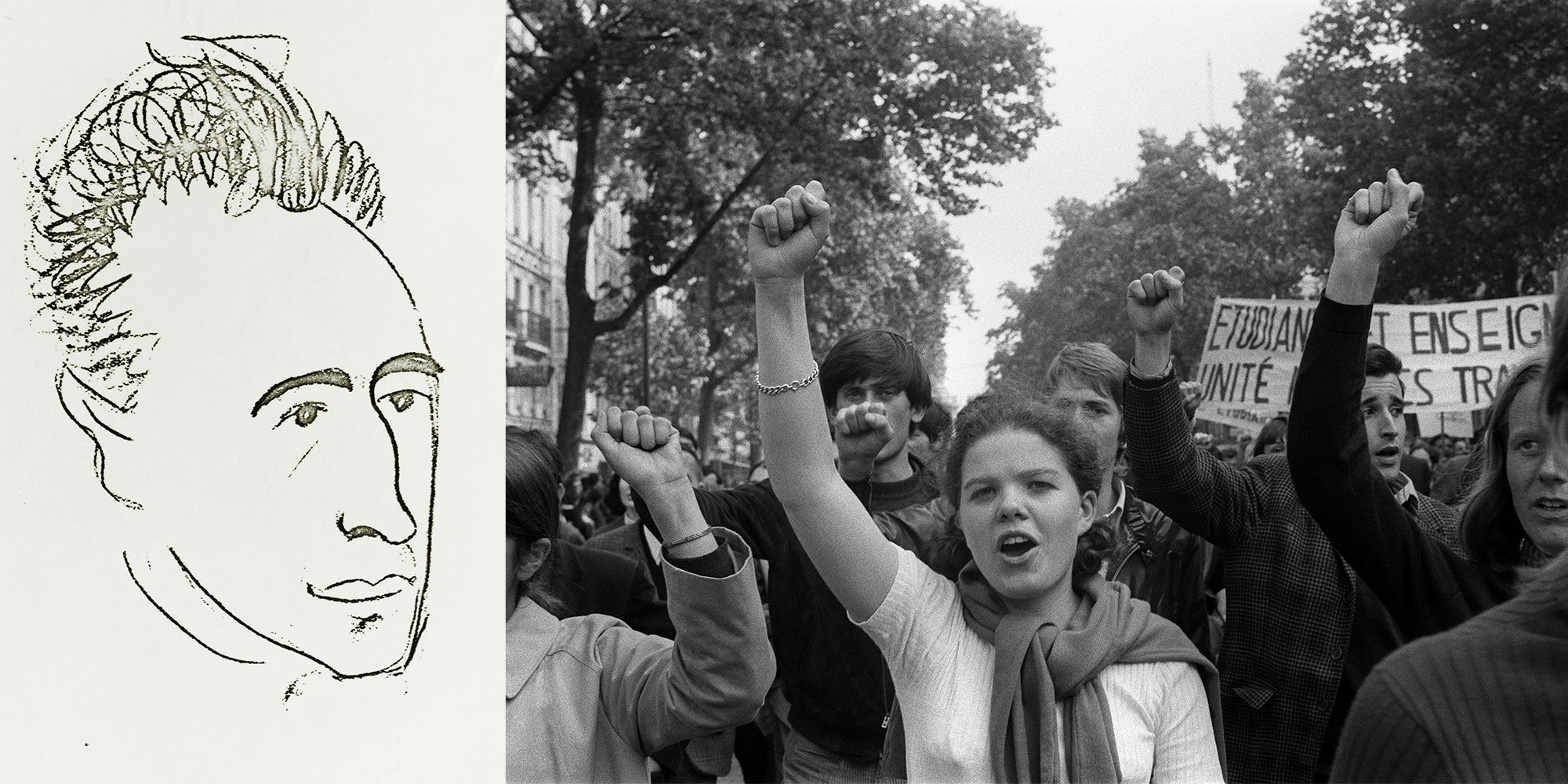

If you have or haven’t heard of Reich, it’s probably thanks to that contraption. Once one of the most esteemed analysts in the world, his book, The Mass Psychology of Fascism, was the most-requested book from the New York Public Library in the 1940s. In 1968, it was thrown at police by student protesters in Berlin, and over in Paris, the Sorbonne was graffitied with Reichian slogans. His anti-authoritarian orgasm theory, which stressed the importance of open relationships and sexual freedom with women’s economic and bodily autonomy, fuelled the student movements of the 1960s. It was Reich who coined the phrases “sexual revolution” and “sexual politics” — way back in the 1930s. He was immensely influential to beat writers Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, JD Salinger; Greenwich Village intellectuals; 70s feminists; and pop culture. Patti Smith and Kate Bush wrote songs about him. And Woody Allen parodied his accumulator in Sleeper.

The device, which was meant to charge up the body’s orgastic energy — deemed a scientific failure by Albert Einstein and was, at least superficially, the reason the American Food and Drug Administration had him imprisoned in Pennsylvania, where he died of heart failure in 1957 — has obscured Reich’s legacy as one of the most radical thinkers of the 20th century.

Yet Burroughs, who featured the box throughout his many novels, Norman Mailer, and others swore by it.

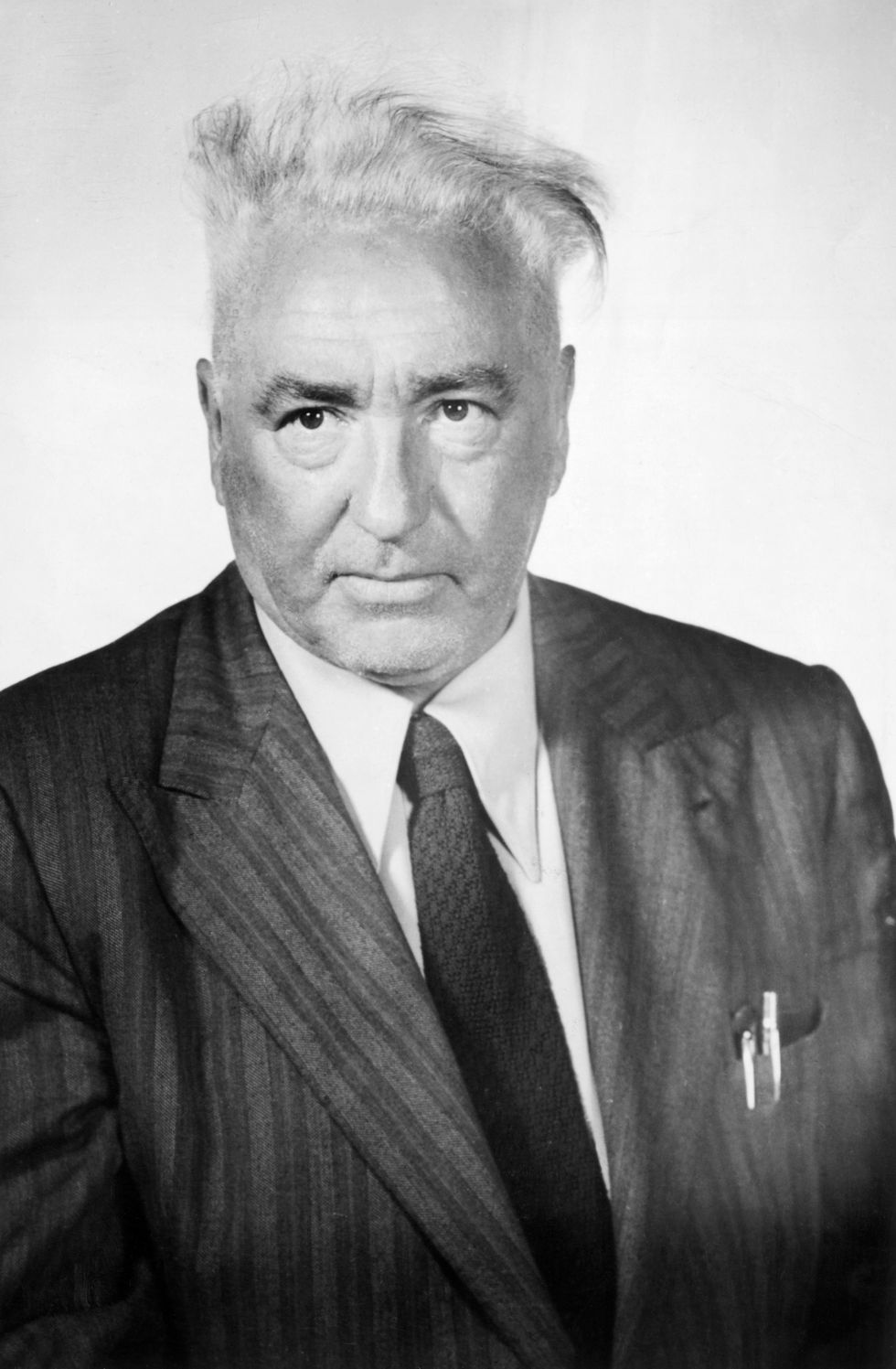

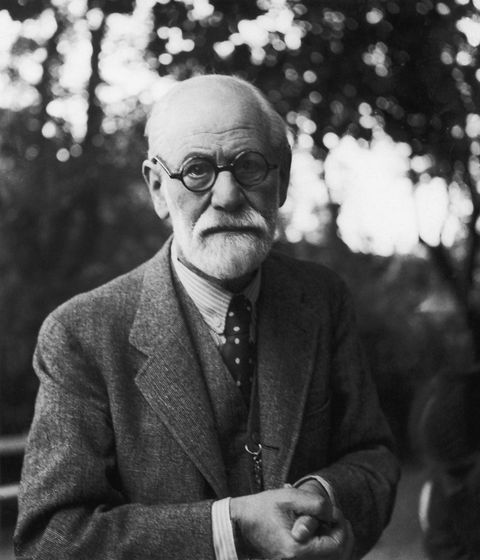

“You don't need to believe in ‘orgone energy’ to follow Reich's argument,” Olivia Laing tells me on a recent call from her garden home in Suffolk. “The ideas that underpin it are valid.” Laing’s new book Everybody, an exploration of bodily liberation, documents the incredibly bizarre and tumultuous life of Reich, Sigmund Freud’s energetic, errant star pupil turned sexual revolutionary. While Freud remains near-deified, Reich is largely forgotten today. Yet many of Reich’s prescient ideas about female sexuality and sexual politics have surpassed his mentor’s — which have not aged well.

As a graduate student in Vienna in the 1920s, Reich was Freud’s favourite protégé. At their first meeting in Freud’s study with its “subterranean atmosphere,” which Laing imagines was, “like a museum or a shipwreck,” Reich recalled Freud as a beautiful animal. The two were instantly excited by one another.

Taken with Freud’s belief that sexual repression was the cause for all neurosis, Reich thought that if repressing sexuality caused illness, then a total sexual release could heal.

Reich was a “sexual evangelist,” Christopher Turner argues in Adventures in the Orgasmatron. “‘There is only one thing wrong with neurotic patients,’” he concluded in The Function of the Orgasm (1927): “‘the lack of full and repeated sexual satisfaction.’” His “orgone” theory was an extension of Freud’s libido, the idea that sexual energy drives life.

After beginning his clinical practise under Freud, Reich moved to Berlin and took over Magnus Hirschfield’s sex reform movement while he was away on tour. He thought the fascism he saw taking over Europe was due to sexual repression. And like past eras, he saw erotic liberation as essential to political emancipation. The shackles of sexual shame and morality must be removed, because sexuality is not only fundamental to being human, but to flourishing. His idea that pure orgasmic release and erotic connection were healthful was an extension of his theory of how the body stores emotional pain as muscular tension (which is used in various disciples today and was probably his biggest impact on psychotherapy).

On the other hand, Freud grew to believe that we need sexual repression to be civilised. And he had an orgasm theory of his own, which, incidentally, aided in the widespread subduing of female sexuality. Freud knew that the source of pleasure for girls is the clitoris. Yet he believed that “mature” women should somehow magically transfer that sensation of the nerve-dense organ (with twice as many nerve-endings in the tip alone compared to the penis) to the largely-insensate vagina. For Freud, the default sexuality was male and straight, and women should accommodate that. This labelled the vast majority of women pathological, as about three quarters never orgasm from vaginal sex, and only around eight percent will come that way reliably.

Although American sexologist Alfred Kinsey debunked Freud’s fallacy in 1953, with his massive survey, Sexual Behaviour in the Human Female (and Masters and Johnson, Shere Hite, and other sex researchers since), finding that women orgasm consistently and within a few minutes with clitoral masturbation, Freud’s massive authority — on a subject most know little about — cemented the pervading myth that the source of women’s orgasm is the vagina. That heterosexist theory has had a plague-like, detrimental effect on sexual inequality. For example, “the orgasm gap,” or the finding that in straight sex encounters, women have a fraction of the orgasms their male partners do, is mainly attributed to a combination of a global lack of clitoral knowledge, a focus on male pleasure, and the cultural suppression of female sexuality (like anti-sex legislation or films, books, etc repeating that myth ad naseum). A 2017 study from the Archives of Sexual Behaviour found that 95 percent of men nearly always orgasm during straight sex, compared to 65 percent of women.

Reich had a much more nuanced and radical understanding of female sexuality. While he was similarly under the misconception that sex should be heterosexual and penetratively-centered, Reich’s belief in the importance of women’s sexual pleasure and his dedication to female sexual agency set him vastly apart from Freud and his contemporaries. While Freud pathologized women getting off, Reich viewed men who “possessed or conquered as many women as possible” as ill. “Most disturbed of all were those men who liked to boast and make a big show of their masculinity.” Such men “experienced no or very little pleasure at the moment of ejaculation, or they experienced the exact opposite, disgust and unpleasure.” Reich thought “disgust, aversion, or decrease of tender impulses toward the partner following” sex “imply an absence of orgastic potency. … Whoever coined the expression ‘Post coitum omnia animalia tristia sunt’ [After intercourse, all animals are sad] must have been orgastically impotent,” he wrote.

When he was 10, his father discovered his mother having an affair, and he beat her over a long period of time until she repeatedly tried to kill herself, and was eventually successful. That traumatic experience no doubt influenced Reich’s empathy and passion for female sexual liberation. In Europe, Reich devoted himself to making contraception and sexual information available with his mobile clinic. He was also an abortion activist. “Freud wasn’t talking about a woman's right to her own body,” Laing says, “whereas Reich spoke literally in those terms vital in our current climate.”

His anti-authoritarian politics were a threat to Freud, who wanted to appease the Nazis to survive. And Freud also had a pattern of disposing of the favoured son who disobeys or challenges him. Reich eventually descended into paranoia, but some of Freud’s other disciples fared far worse and committed suicide. Carl Jung was cast out for allegedly being fascist; Reich for being vehemently antifascist. He was expelled from the Communist Party in 1933 for being too radical, and one year later from the International Psychoanalytical Association. After fleeing the Nazis, he was kicked out of many European countries, before finally arriving in New York City in 1939, hoping his ideas would be better received.

Instead, Reich was placed under surveillance almost immediately after entering the US. The FBI had a 789-page file on him. Harper’s Magazine didn’t help by telling Americans, in 1947, that he was the leader of “a new cult of sex and anarchy.” Like many brilliant people whose ideas remain radical nearly a century on, that lifelong rejection and misreading of his work took a toll on his mental health. With a lack of institutional support to keep his ideas in check, he drifted toward delusion toward the end of his life. The FDA blew their entire budget on investigating him, and in 1954, he was sentenced to two years in prison after refusing to cease the sale of his accumulator.

The accumulators in his research laboratory in Rangeley, Maine, thousands of copies of his journals and his 11 books — some which did not mention the accumulator — were accused of false advertising, and, like the Nazis did with his and Freud’s books back in Berlin, the American government burned them. A man who devoted his life to freeing others died in a prison cell in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary, eight months after his sentence, at the age of 60.

Reich’s paranoia, in other words, was not unwarranted. “The accumulator might be kind of wacko,” Laing clarifies, “but it certainly wasn't dangerous.” So then why was there that level of international persecution?

“Because there's something about the recognition of sexuality that is deeply threatening to people,” Laing says. Regardless of how omnipresent it is, “sex is still taboo.”

Within that lingering taboo it’s women’s sexuality that threatens most. From female genital mutilation to to the continued struggle for abortion and contraception access, girls’ and women’s sexual bodies have been tightly controlled for centuries. The recent freak-out over rappers Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s Grammy performance of “WAP” — a manifesto of sexual agency with lyrics like, “I don’t want to spit, I want to gulp” — is one example. Like a thousand songs before, the lyrics are an expression of sexual appetite. What caused the FCC to receive more than 1,000 complaints (from every gender) was that it was women, and not men, with the appetite. With that lingering sexual double standard saturated throughout our culture, it’s no wonder so many people don’t know how to get women off.

Reich saw that suppression. He knew first-hand the relationship between constraints on women’s sexual freedom and an unfree society. Like much of queer theory today, he viewed monogamy and the nuclear family as inherently patriarchal institutions hampering women’s economic freedom and well-being. He advocated for “lasting love relationships” not encoded by law, and practised open non-monogamy himself. “What he really understood,” Laing says, “are the social conditions under which female sexuality takes place, and the need for those to change. Namely, the risk of violence, death, and unwanted pregnancy. Reich was misread by misogynist men like Norman Mailer as “this apocalyptic orgasm guy and this kind of quick, cheesy understanding of what sexual liberation is,” Laing tells me. “Actually, he's much more driven by a desire for women to be able to experience a free sexuality without what happened to his mother. Freud wasn’t talking about the right to abortion or a woman's right to her own body, but Reich spoke literally in those terms vital to our present climate.”

Intellectuals from James Baldwin to Michel Foucault mocked Reich. If sex is everywhere, where’s Reich’s utopia, critics wondered. But that’s a mute question, because we’re far from meeting the conditions he sought. Sexual activity is not sexual pleasure. Like Pier Paolo Pasolini (another isolated cultural figure who had a transformative vision of sex and was hated across the political spectrum), Reich was skeptical of the postwar countercultural permissiveness. Pasolini and Reich predicted the capitalist commodification of sex that we now have with Tinder and Grindr. The still-common Madonna/ whore dichotomy of straight sex — where some men slot women into a binary of “respectful” sex with an emotional connection (for more demure potential partners and mothers of their children) or “dirty” detached sex (for women who openly enjoy sex) was not Reich’s vision of sexual liberation. There was nothing casual about the depth of intimacy, vulnerability, and tenderness Reich envisioned. Women as orifice-receptacles for semen — the confusion of domination with sex (outside a BDSM context) — was not what he had in mind. Reciprocation and connectedness were vital to Reichian sensuality: “It is not just to fuck, you understand, not the embrace in itself, not the intercourse. It is the real emotional experience of the loss of your ego, of your whole spiritual self,” he wrote in Reich Speaks of Freud.

Reich was also transgressive for his belief in people. Like the contemporary Dutch economist Rutger Bregman, Reich thought that when given the right conditions, people will govern themselves. Those swift to label this utopian naivete, are missing the complexity. The idea is more nuanced than simply that all people are fundamentally good. If you treat people like criminals who must be watched (as Freud believed was necessary), they will behave as such. Expect dignity by providing the social equity necessary, and most will oblige. In the same vein, if people were given the freedom to express their sexualities and experience the full capacity of their eroticism safely, sanely, and with exquisite relish, is it such a ridiculous notion that other social ills will lessen?

After all, Reich, like Marvin Gaye, was actually right in his belief in sexual healing. There are now numerous studies which link improved mental and physical health and increased feelings of empathy, self-esteem, and autonomy with orgasm and sexual enjoyment. That post-sex glow is an actual physiological phenomenon.

Slow-going as it’s been, "a sexual revolution is in progress. And,” as Reich put it, “no power on earth will stop it.” To cynically throw up our hands to the futility of Freud’s death drive is the much easier position. Reich was persecuted for believing that changing the world is possible, and for having the gall to try. That belief that human beings are capable of greater tenderness is still threatening, because it means that, as we emerge from our plague-lockdowns, collectively longing for touch and connection, we could abandon our ancient sexual morality. We could retire the compulsory monogamy and other forms of ownership of girls’ and women’s bodies, and trade in the religiously-proscribed reproductively-obsessed sex for the mutually-gratifying erotically-nourishing variety — if we wanted. And maybe then, every body could be freer to enjoy more pleasure.

Mary Katharine Tramontana is a writer covering sexual politics and culture for The New York Times, Playboy, and other outlets. You can follow her on Twitter at @MKTramontana or on Instagram at @marykatharinetramontana. She lives in Berlin.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts