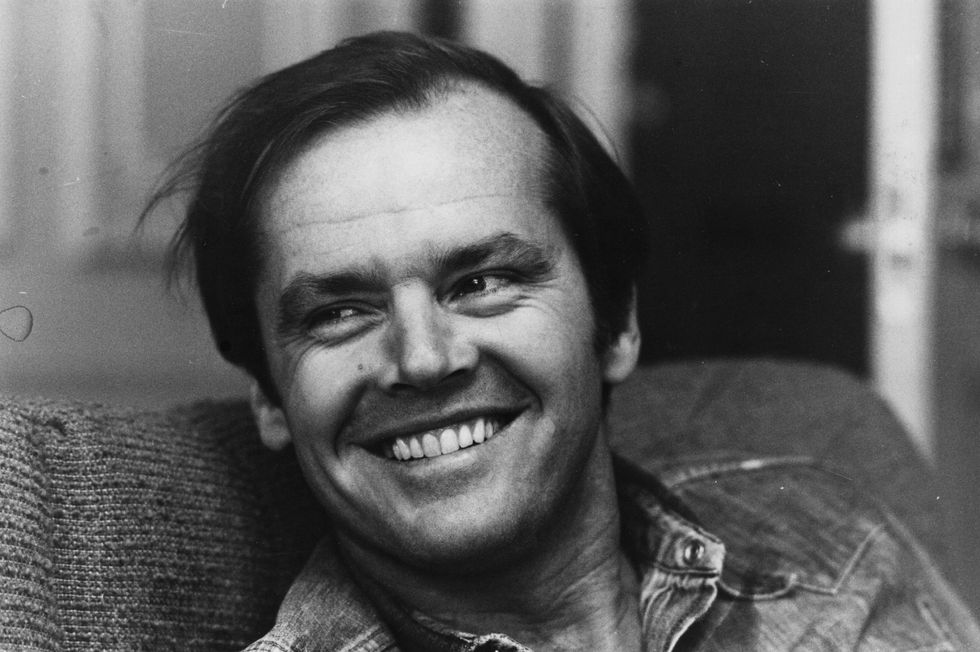

Last week, as masks became compulsory in shops in the UK, a women held the door open for me as I walked out a furniture shop, which I had slipped into for a blast of air conditioning. I smiled as she held the door for a few seconds, before panicking that she couldn't see my face. I started pulling a maniac, Joker-esque grin so that she might see my mask stretching to accommodate it and know that I really was grateful.

A smile is a social cue we beam out to the world every day: a muscle movement with which we send signals to strangers. There are thousands of messages a smile can smuggle: the flat-mouthed twitch when you catch someone's eye as you're walking past them, the curved beam of politeness to say thanks – as I poorly attempted in the furniture store – or the wide grin when you spot someone waiting for you at the airport.

We associate smiling with happiness but in fact scientists have identified 19 distinct types of smile, confirming Herman Melville's idea that the smile is "the chosen vehicle for all ambiguities". Of this array of different smiles, only six are used to signal we are happy, with the others signalling fear, disappointment, embarrassment, and other mixed emotions.

Perhaps the most famous of these smiles is the Duchenne smile, named after scientist Guillaume Duchenne, whose research mapped the muscles on the body and their connection to facial expressions. Duchenne's work found that the 'felt' smile – the one that signals true joy – occurs when the zygomatic major muscle, which is found in the cheek, tugs at the corners of the mouth. This then leads the orbicularis oculi muscle, which is around the eye, to pull up the cheeks and cause the ‘twinkling eyes’ that define this warm, lasting smile.

So though we think of a smile as taking place in our mouths, that curl of the lips is really a see-saw in which the mouth levers the eyes into action. Duchenne's research went one further, showing that the a "true smile" is in the eyes, as the crow's feet wrinkle together. Unlike the mouth smile, which obeys our will more easily, the eye smile is harder to fake. "The muscle around the eye is only brought into play by a true feeling, an agreeable emotion," he wrote. "Its inertia in smiling unmasks a false friend."

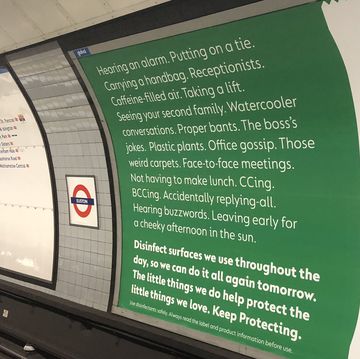

Unlike their Eastern counterparts, smiley faces in Western cultures focus more on the mouth than the eyes, which might be why many feel wearing a mask feels robotic and unexpressive. As an article in the New York Times from last month argued, "masks not only hide grins; they can also make it harder for people to display a whole range of emotions including discomfort, dismay or disdain".

The debate about whether a mask infringes our liberties, which has taken hold particularly in the United States, is often centred around the idea that masks muzzle us like animals, leaving us unable to communicate. What this argument ignores is what we are left when wearing a mask: the eyes. Eyes are a window into our emotions that we only think of as our way to see others, rather than something that gives away how we feel.

I've started trying to smile with my eyes when out wearing my mask, even though at first it felt like it might scare young children I came into contact with. But what I quickly saw, from looking out for the giveaway winkles around the eyes of strangers, is that a mask doesn't hide a true smile – it reveals a fake one.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts