My dad’s basketball coach once said to him, “Markovits, you may be slow, but you sure are weak.” His big brother, my Uncle Bob, was a giant, about 6ft 7in and north of 20 stone, but my father was slighter, narrower, a little stoop-shouldered, and barely scraped six feet. He was also, in his way, a much better athlete than I would ever be: a scratch golfer in high school, a decent first baseman. He once won the section nine New York State singles bowling championship. But he could never jump much.

When I was six or seven, he built a concrete half-court in our backyard in Austin, Texas. This is where I spent most of my childhood. Shooting a basketball is like learning to write — it’s something you have to practise on your own. By the time I was 12 or 13, I could reliably knock down 20-footers. I was almost as tall as my dad and quick enough that he had to work to beat me at one-on-one. But it didn’t occur to me that I might someday be able to dunk. I was my father’s son.

Basketball is social and hierarchical, and the problem with learning in your backyard is that you don’t figure out how to navigate a locker room full of boys. My dad wanted me to play high-school basketball, so I played, but I never liked it much. On Friday nights, I’d ride the bus after school with the rest of my teammates to some game and sit on the bench for a few hours while my dad watched from the stands; afterwards, he’d drive me home. I didn’t even have to shower.

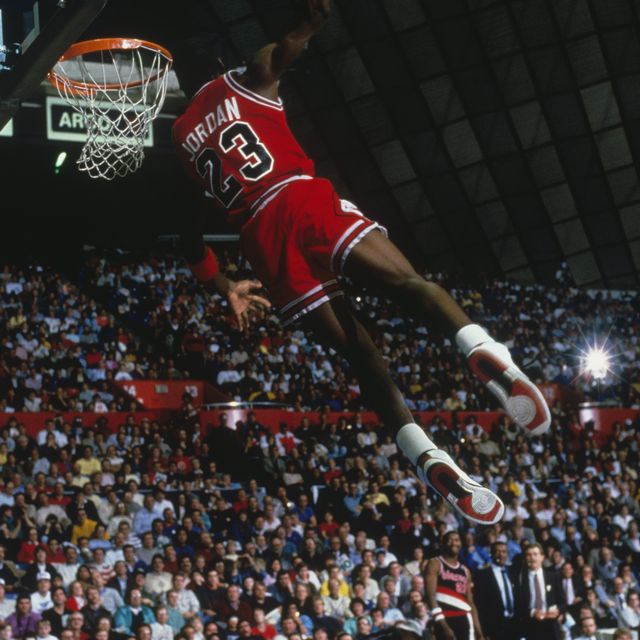

Nora Ephron once wrote a brilliantly funny essay (in Esquire, in fact) about what it’s like to be a teenage girl whose friends are all getting breasts. Replace breasts with dunking, for a certain kind of teenage boy. If only I could jam... That would show ’em. In practice, every day after school, I watched my teammates dunk and felt like that kid in the William Blake picture, standing at the bottom of a long imaginary ladder to the moon. The caption reads, “I want! I want!” The rim of a basketball hoop is 10 feet off the ground, but it seemed to me as unreachable as that moon.

The problem with learning to dunk is that you can only actually practise it once you can already do it. When I was 16, we moved to Berlin for a year. Michael Jordan won his first NBA championship that season; I watched the series on the local Armed Forces Network. By that point, I was almost as tall as my uncle, 6ft 6in — Jordan’s height. The zeitgeist and my adolescence aligned. There was a hoop in the school playground that was maybe a little low. I once saw a kid dunking on it and thought, “He doesn’t look so different from me.”

There was no Eureka moment. Your first dunks are usually a matter of interpretation —you kind of squeeze it over and afterwards go, “Does that count?” But when we got back to Texas, it became an obsession. I used to spend hours in the backyard, just . . . banging on the rim. All year long, I had little pixels of blood buried under the skin of my fingers. When friends came over to shoot hoops, suddenly they had to worry about getting dunked on. I felt like Harry Potter when the letter shows up in the mail, meaning: you’re one of them.

And then I quit the team.

There’s nothing really to explain this fact except that the gap between how I played at home, in my backyard, on my father’s court among friends, and how I played at school had grown too wide. It was like a kind of selective mutism. I couldn’t say, in “public”, the things that I wanted to say, and my frustration with myself was too hard to bear. So I quit, just before the team made a run to the semi-finals of the state championships and became the toast of the school.

For the next six years, I went through the usual coming-of-age stuff, but part of what I had to deal with was not just girls and jobs, but my failures on the court. I had a whole childhood of frustrations to work out. Two of the three most significant moments of my life were the births of my children. The third happened in the Busa National Championships, when I was playing for my grad-school basketball team. In a close second half, I cut backdoor against a tight defence, caught a bounce pass, took a step and rose up. Loughborough had a seven-footer at the rim, but he was late on his rotation and by the time he got there I had dunked in his face.

Sometimes, on my increasingly middle-aged jogs, I wonder how much money I’d be willing to pay for video footage of that play. If only to show my dad. And my kids. A thousand pounds? Five thousand? Twenty?

Because this is the problem with dunking. If the guys you play against get older and slower, it doesn’t matter that you’re older and slower, too. But the rim just stays where it is. I wonder if the last time I dunk will be any more definitive than the first. One summer ago, in perfect conditions, riding a wave of the right kind of jet lag, after a little loose pick-up with old friends to get my juices flowing . . . on my childhood court, with a super-grippy basketball, I managed to rattle one down in front of witnesses. Was that the last time?Because on most days, my legs feel like rented legs, and when I run at the rim I get only the old comic “boing” of my teenage years as ball bounces off iron. Afterwards, like Blake’s boy staring at the moon, I look up at the hoop and think, “I want, I want.”

Benjamin Markovits is the author of several books, most recently The Sidekick. This piece appears in the Autumn 2022 issue of Esquire, out now