Patrick Moylett, managing director of Harringtons of Fulham, a specialist used car dealership on the New King’s Road, is demure in sheepskin coat, cashmere V-neck and pressed blue jeans. He doesn’t really look like a pioneer of gay consumerism. In fact, he looks like what he is: a used car dealer, albeit one peddling his trade in the more refined quarters of west London. In common with all successful businessmen, Moylett’s career includes a litany of failed enterprises. Also in common with all successful businessmen, it features enough victories to keep him in fine woollens.

The Moyletts are a large family of high-achieving Dubliners: Patrick’s brother Johnnie Fingers was the original keyboardist in The Boomtown Rats, and his sister Regine is a successful music publicity agent and manager with clients including U2, The Clash, Blur and Gorillaz. They came of age in the late 1970s, in an Ireland beginning to liberalise its economy and watching its society follow suit. In Dublin, lank-haired youngsters were turning derelict buildings into music venues, where the likes of U2 and the Rats cut their teeth.

As the Catholic church’s grip on the nation eased, its influence on people’s private lives was becoming less obtrusive. In 1979, the Irish government allowed condoms to be sold in pharmacies to customers with a “family planning” prescription; but the new bill was complicated, with the Dàil writing into law exactly what they could, and couldn’t, be used for — something Taoiseach Charles Haughey famously described as “an Irish solution to an Irish problem”.

Around that time, fresh from a gap year in Paris — during which he had tried to sell socks with toes, door spyholes and Irish tweed — Patrick Moylett was back in his hometown looking for a new venture. Despite the legislative strictures, he could sense the coming tide, so decided to take a punt on sex, managing to obtain the first licence to import condoms into the republic. A good Catholic boy, his decision wasn’t without its long nights of the (rubber) soul: “I was credulous in those days, so I rang the bishop of Ireland to ask if I was misleading people. His assistant said, ‘Call back at the same time next Friday, 10 to six,’ and the answer was, ‘Don’t quote me… but go ahead.’”

Thus, the Frederick Trading Company was born, so others wouldn’t have to be. Moylett began importing condoms from a factory in West Germany, where a number of manufacturers had popped up to service the large concentration of foreign Nato troops. He advertised his wares via mail order in specialist magazines and the business received a boost when he was invited to appear on television. “Ireland was, excuse the pun, a virgin market,” he tells me, “and if you imported one new thing, you could get on this programme, The Late Late Show, and the whole country would know about it.”

Irish fame had a drawback: infamy. Moylett became something of a pariah, a hairy corrupter of the youth. When he was caught selling a house using a lottery system, illegal under Irish law, the Gardaí made an example of him. After a couple of weeks behind bars, he decided to emigrate to London, leaving his condom business in the dependable hands of his younger sister.

England in 1984 was as much a land of anonymity as one of opportunity for a young Irishman. Orwell’s fictional annus horribilis was, in reality, the year of the miners’ strike, record high unemployment and a rapid escalation of the Aids crisis. In New York and San Francisco, the roiling epicentres of the virus, it was already the number one cause of disease-related death in young people. Horrific double-page spreads in major newspapers listed weekly Aids-related fatalities.

The consummate wheeler-dealer, Moylett quickly found a new racket: cassette tapes that resembled the old reel-to-reel variety. In early autumn, he was sitting in the lobby of Time Out’s Soho offices, waiting to place an ad for his latest venture, when he overheard two journalists discussing the anti-competition tactics of Durex, manoeuvres they dubbed the “London rubber wars”. Time Out was radical back then; in 1981, it became the first mainstream publication to include a dedicated gay and lesbian section. Moylett’s lobby companions were aghast that, despite their importance, due to the intransigence and prejudice of government and the country’s largest manufacturer, there was a shortage of the most effective weapon for halting the spread of Aids: condoms. Hastily founded clinics, activist groups and charities were finding cheap, durable prophylactics hard to come by. Moylett’s ears pricked up.

He had a condom business, he told them, and he’d be more than happy to supply those clinics. And… would they consider interviewing him? They would. So, in the following issue of London’s premier listings magazine, the young Irishman declared condoms the “aspirin of Aids”. Moylett was being slightly elastic with the truth. Thanks to a moment of pure happenstance straight out of the pre-internet age, he had his free publicity; what he didn’t have was any condoms, as they were in Ireland. But, natural-born salespeople are perceptive and know the importance of seizing an opportunity when it comes along.

Britain’s relationship with condoms was less Manichean than Ireland’s. That said, though their primary function had historically been prophylactic, they could only be marketed for contraceptive use. This was due to the 1917 Venereal Disease Act, passed during World War I to combat an epidemic of gonorrhoea and syphilis and a subsequent outbreak of snake-oil salesmen. Dud remedies were so rife, parliament ruled that only qualified doctors could legally treat sexually transmitted diseases with prescribed medicines.

Today, their preventative virtues are beyond doubt. But even in late 1984, three years after the first known death from Aids in the UK, and a year after its viral antecedent (HIV) had been formally identified by researchers at the Pasteur Institute in France, condoms’ efficacy in combating the disease was still to receive universal endorsement, and their usage was far from widespread.

Until the mid-19th century, condoms were tough, reusable sheaths usually fashioned from sheep gut. When American chemist Charles Goodyear discovered the vulcanisation process in 1844, manufacturers realised they could be mass-produced using rubber. Still, they remained associated with immorality (hence the insult “scumbag”) and prostitution (possessing a condom was frequently used as evidence in convictions).

The London Rubber Company was founded in 1915 and by the 1930s its main brand Durex had become the UK market leader. When the Aids crisis hit, it boasted up to 95 per cent of the market share. Long before Moylett came to town, the LRC had engaged in anti-competition tactics to protect its monopoly by discrediting rivals, detailed in a recent book on the company, Protective Practices: A History of the London Rubber Company and the Condom Business by Jessica Borge. In the early 1960s, when the pill arrived on British shores, the company aggressively encouraged some within the medical fraternity to produce literature questioning the new contraceptive’s safety.

Later, in 1975, the Monopolies and Mergers Commission published a damning report into the now renamed LRC International Limited’s anti-competitive actions that resulted in the imposition of price controls on its products, a result that caused leading campaigner and Welsh Labour MP Leo Abse to quip that he’d “brought down the cost of loving”.

As Borge writes, “In the 1970s, London Rubber had privately stated that it wished to avoid making any public connection with disease,” so when Aids emerged, its silence was unsurprising. And, considering its prior tactics, neither was its reaction to upstart rivals.

A few days after his Time Out interview, Moylett received a call from Charles Farthing, a New Zealand doctor treating Aids patients at St Stephen’s Hospital, Chelsea. Dr Farthing was a perspicacious figure both atypical in his pioneering trials of antiretroviral drugs, and emblematic of the wider struggle: one fought by courageous individuals against overwhelming indifference.

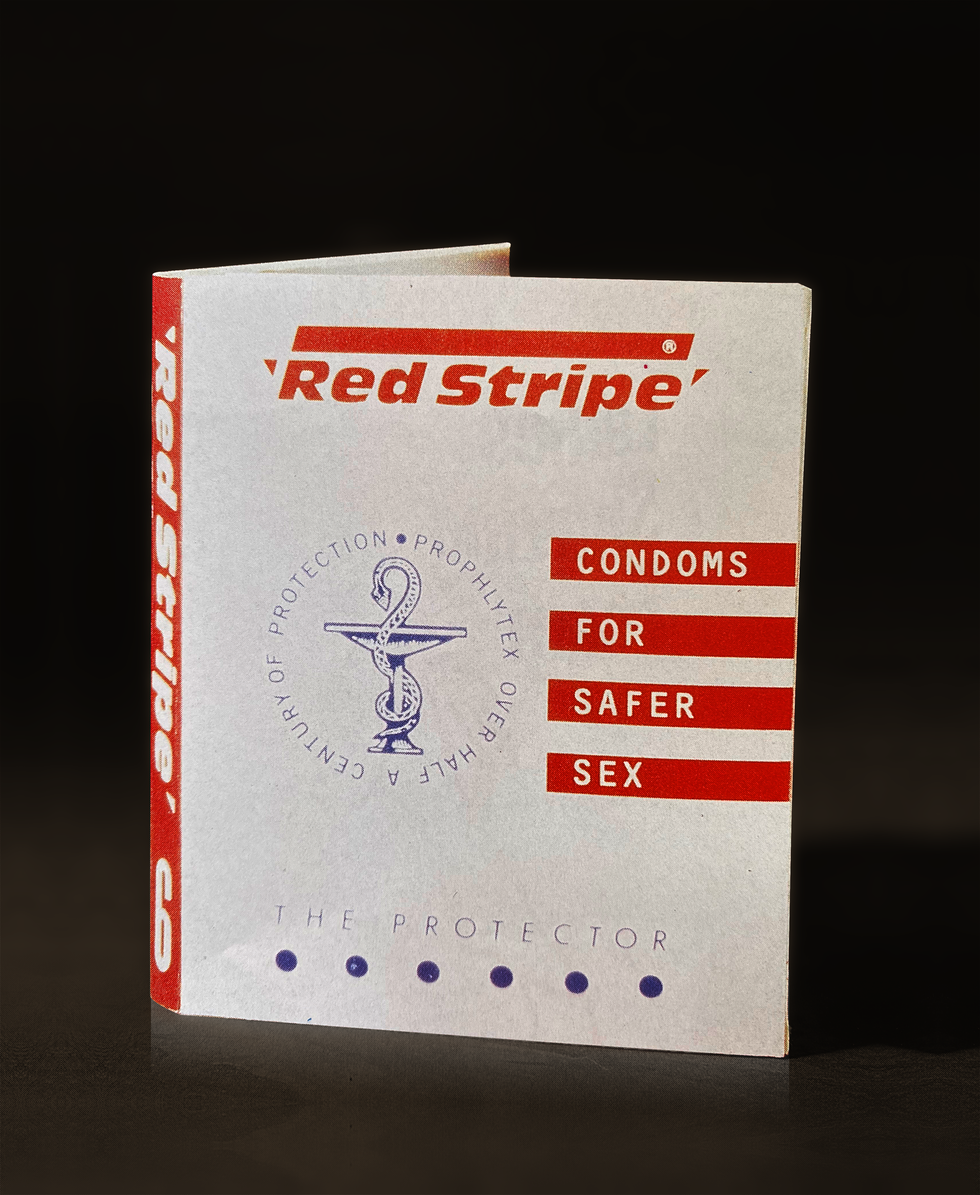

The pair arranged a meeting to which Moylett took three different boxes of the condoms he was selling in Ireland. “I said to Dr Farthing, I thought gay men would prefer the ones without a semen reservoir — it being anyway superfluous — because of the way they looked.” These were packaged in a red-striped pack.

Like other clinicians and campaigners, Farthing was desperate for a condom strong enough to recommend for anal sex. Some gay activists were advocating “double-bagging” which actually increased the danger of condoms tearing due to added friction. After the doctor placed an order for several thousand, Moylett rang Companies House and registered a trademark for “Red Stripe, the strong condom”. Then he called a bank. The next day a chequebook arrived, shortly followed by a cheque from the government as part of its new Enterprise Allowance Scheme.

On Farthing’s encouragement, the NHS began ordering 50,000 Red Stripe condoms per week. Moylett’s basement flat, the centre of his operation, was soon stacked floor-to-ceiling with boxes. His landlady, who lived upstairs, asked him what they contained. When he told her she said, “I think that’s the most condoms we’ve ever had in the house.”

While Moylett’s home was brimming with johnnies, charities like the Terrence Higgins Trust, founded in 1983 and named in memory of one of the UK’s first Aids fatalities, were still scrabbling around for them. Nicholas Partridge, a future CEO of the trust, was then working as a volunteer at its one-room office in London’s Clerkenwell. He remembers there being “real anger at both the cost and lack of availability of condoms… the LRC would not engage, they really saw themselves as selling a wholesome family product.” Durex’s fuddy-duddy adverts featured hand-holding, heterosexual couples, or men’s barbers offering “something for the weekend, sir?”

Since television was off limits, and the LRC had the few men’s magazines permitted to publish condom adverts tied up, Moylett focused on guerrilla tactics: speaking to journalists about Aids prevention and seeking partnerships with the likes of Levi’s and Katharine Hamnett. Today, when the so-called pink pound is courted with zeal, it’s hard to imagine the stigma attached to such an enterprise; as Partridge says, “only the bravest brands supported Aids work.”

The number of Aids infections continued to rise, and widespread homophobia (always latent) mirrored their trajectory, both soon reaching appalling new heights. The British tabloid press used fear to unleash a campaign of hate. Before the 24-hour news cycle, front pages screamed about “the gay plague”, “gay menace” and “gay killer bug”. Newspapers ran heinous surveys seeking readers’ views on propositions advocating sterilisation or imprisonment for Aids sufferers. The News of the World became obsessed with an estate in Chelsea “aptly named World’s End” where a number of residents were HIV positive and living alongside “hundreds of healthy families”. Another hugely popular tabloid used the graphic of a man with half the skin on his face removed, revealing the skeleton beneath, to enable its readers to quickly identify Aids stories.

Those in power didn’t fare much better. Right-wing governments on both sides of the Atlantic preached sermons on the sanctity of family life. The administrations of Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in America were both disinclined to be seen as helping those whose infections were considered a direct result of immoral behaviour. Much of their electoral success was attributed to promises made to curb the so-called excesses of the preceding decades and take their countries back to a make-believe before-time of moral and financial probity.

Politicians advocating government intervention in the escalating health crisis had to confront not just high-level ambivalence, but outright antipathy: the Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police, James Anderton, blamed Aids victims for “swirling about in a human cesspit of their own making”. Five years passed from the first recorded UK fatality before the Thatcher government took any decisive action to confront Aids.

British newspapers began covering the pandemic regularly, and with increasing hysteria, in the mid-1980s. By then, teen magazines had been discussing the disease in a more measured and informative tone for at least two years. One such publication was Student, Richard Branson’s first venture which he’d launched in 1968. A year later, he opened the Student Advisory Service based in central London, offering young people information on issues such as sexual health and drug abuse. In the 1960s, if you were young, the past really was a foreign country, but it was one whose denizens continued to rule the present. The authorities became so worried by Branson’s attempts to inform the youth about sex that they prosecuted him under the aforementioned 1917 act.

But he was canny and brave. Branson became an early advocate for gay rights, and Virgin and its subsidiaries was perhaps the first British brand to welcome homosexual consumers. The Student Advisory Centre he launched on the back of Student provided an informal network and haven for young gay men newly arrived in London. In 1981, the entrepreneur bought Heaven nightclub in London’s Charing Cross. It was here that Terry Higgins would collapse and die.

The bronzed billionaire has — sometimes rightly, sometimes wrongly — drawn his fair share of criticism, especially of late. But the 1980s Aids crisis was a time when his iconoclastic entrepreneurialism helped shatter societal prejudice. The successful business people I’ve come across share two traits: charm and a lack of qualms.

Patrick Moylett would be the first to admit he didn’t start Red Stripe condoms for any other reason than money. As orders piled up, his rock star brother Johnnie wrote to him complaining that, “I was sitting back coining it while he was working his arse off touring the world”. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman famously said the first social responsibility of business is to maximise profit. In 1987, as Aids deaths in Europe and North America peaked, and Adweek declared the Aids crisis one of its “hottest markets” due to an abundance of “free publicity”, Branson started a not-for-profit condom company: Mates were half the price of market leader Durex and were sold heavily subsidised to clinics, with all profits donated to Aids charities.

Perhaps more significantly, the brand helped change the perception of safe sex. As Branson tells me over the phone from Necker Island, his private Caribbean home, “What we decided to do was launch a really fun condom.” In common with brands like Red Stripe, Jiffi (slogan: “Come in a Jiffi”), Ramses and Arouser, Branson’s Mates made a conscious effort to shed the traditionalist (straight) tones of their more established rivals and, as Moylett put it, “shoot from the hip… or the area next to it.”

Mates advertised in gay magazines urging readers to “be a carrier”, not of HIV but condoms. Taglines such as “They’re awfully fiddly to put on. But isn’t that half the fun?” turned the usual mood-killer of putting on a condom into something erotic. As Richard Davenport-Hines wrote in his book Sex, Death and Punishment: “Instead of badgering people into chastity, or frightening people into the sort of panic in which bad, impulsive decisions get taken, Mates have encouraged the taking of individual decisions in a relaxed atmosphere.”

The brand also captured a previously unconquerable market: women. Partly this was down to Branson’s strategy of selling condoms in hitherto off-limits locations like supermarkets, garages and fast-food outlets. Within a year of its founding, Mates had taken 20 per cent of the market. This success wasn’t merely due to undercutting Durex — many thought their low price the sign of an inferior product — in fact, when Mates’ price increased, its sales did too. Branson estimated that at least half of its customers were new users, many of them young, straight people worried about Aids.

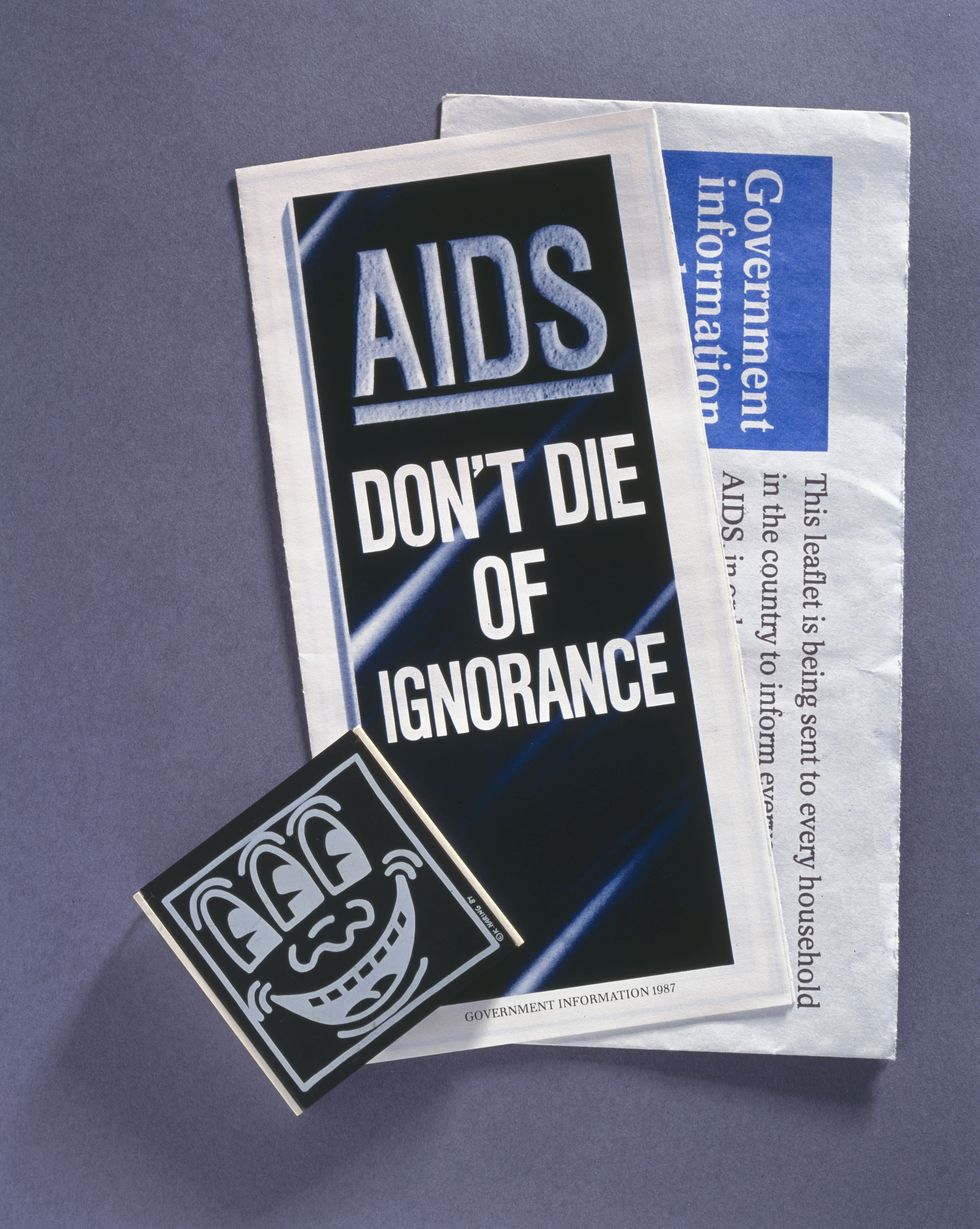

Nineteen-eighty-seven was a turning point in the Aids crisis. It was also, not coincidentally, the year the virus began to infect more heterosexual people. Thanks to the efforts of Thatcher’s health secretary Norman Fowler, and a more liberal-minded civil service, the prime minister consented to a national information campaign. But even then, there was much wrangling over whether it should be focused on harm minimisation or exhortations to cease high-risk behaviours, ie, anal sex. One of Aids’ most pernicious effects was to make gay sex synonymous with disease. As many public officials claimed celibacy was the only way to guarantee protection, brands like Mates and Red Stripe, and politicians like Fowler, insisted anal sex was not intrinsically dangerous.

Still, the UK government’s eventual campaign “Don’t Die of Ignorance” was pretty scary. It’s mostly remembered today for two ominous television spots, both directed by Nicolas Roeg, one featuring cracking icebergs and the other, voiced by John Hurt, with colossal tombstones bearing a one-word epitaph: Aids. But the message, distributed in leaflets to every British home, was the first government-sponsored, nationwide Aids campaign on the planet. Among its safe sex edicts it implored men to sheath up.

During that pandemic, there was no vaccine into which billions were being poured but, by 1987, there was near universal acceptance of condoms’ essential role in saving lives. As Nicholas Partridge, who was assisting on the helpline at the London Lesbian and Gay Switchboard, told me, “Even if someone called for the opening hours of The Black Cap pub in Camden, we’d tell them about condoms.” Fowler declared “information is the only vaccine” but he struggled to administer this using any method other than fear.

Branson had another idea for his Mates. “In my opinion, the fear-mongering was counter-productive, people were terrified,” he says. When he convinced the controller of BBC One, Michael Grade, to broadcast not only the first television condom commercial, but also the first and only commercial ever shown on the channel, the tone was jocular not menacing. “The one he [Grade] particularly liked was a young man walking sheepishly into a chemist,” says Branson. “When he finally musters the courage to ask for condoms, the woman behind the counter calls out [to the pharmacist]: ‘Mr Williams, how much are these Mates condoms?’”

New condom brands helped to drag sex out of the gutter, and in doing so boosted the kind of suggestive advertising tropes which are now ubiquitous.

But, like sharks, monopolists don’t rest. “Our sales were going really well, then we saw our products were being removed from the shelves. Durex were visiting chemists and making it very worthwhile for them not to sell Mates,” Branson tells me. Moylett reports similar protective practices, claiming even fouler play: allegedly, LRC invited the late Lynn Faulds Wood, presenter of TV’s Watchdog, to join its board. Then, it engineered a hit-job on Red Stripe, ensuring its rubber’s durability was tested on-air. How does Moylett know all this? “Victor O’Shaughnessy, the LRC’s director, told me over lunch at the RAC a week after the programme aired.”

Since Red Stripe traded on its superior strength, and had thus been appropriated by gay men, this caused a backlash from a community well-versed in betrayal. In April 1987, an article in Nottingham gay paper The Sparrows’ Nest, written after TV’s Watchdog programme tested nine condom brands available in the UK, declared under the headline “We Were Conned”: “Red Stripe condoms marketed to gay men as the strongest for protection against Aids are no stronger than other sheaths on sale in the UK.”

Moylett got a call from a friend who worked in the NHS telling him of an internal memo advising doctors not to order his products. The bubble had burst; his days as a “rubber baron” were over. Still, he’s unequivocal about his demise: “I don’t rue my failure. I made a bit of dosh and I like to think I played a small role in moving the conversation in the right direction… towards the bedroom.” After Red Stripe ceased operating, the LRC brought out a condom with a red-striped packet it called Safe Play. Branson also left the game. In 1988, he sold Mates. “It had done its purpose, getting people to wear condoms,” he said.

Advocates of safe sex had certainly succeeded in their mission: in 1988, condom sales increased in the UK by 20 per cent and, for the first time since the introduction of the pill, they were the most popular form of birth control for married couples. As Jessica Borge puts it, “the image of condoms in the public consciousness had been virtually normalised as ‘just another healthcare product.’” Before 1981, virtually no gay men used condoms, and yet, according to one study, just six years later, 78 per cent in America always wore one during intercourse. This mass behavioural change helped turn the tide in the pandemic.

On paper, the 1980s Aids crisis should have created a bonanza for condom manufacturers. Yet by 1994, partly due to disastrous product diversification and poor investments, but also over-supply and longer shelf lives for condoms, the old London Rubber Company (by this time known as London International Group) was nearing collapse. With it went the last factory, located in Chingford, still producing condoms in the UK. Production shifted to Malaysia and in 1999 the Durex brand was sold on.

Since 1981, over 32m people worldwide have died from Aids. It’s impossible to discern how many lives were saved through safe sex advocacy; Partridge estimates at least 100,000 in Britain alone. The London rubber wars has no memorials under which we can stand to attention, but some of its veterans are worthy of our respect. After all, in any pandemic, who doesn’t want to know that someone, somewhere, is offering us protection?

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts