“I can’t,” says Kim Jones. He’s been asked to put into words a famous silhouette created by Yves Saint Laurent, one of his predecessors at the house of Christian Dior, in Paris. “You have to see it to understand it.” He slices the air with his hand, fingers slightly curved to form a serpentine line. “For me,” Jones says, “there’s a fluidity to his line that makes it very, very sensual. I think that’s what’s so appealing about his work.”

Saint Laurent was celebrated, as was Christian Dior before him, for his tailoring, among other things, which borrowed the structure and conventions of formal men’s clothes and applied them to womenswear, most famously in the case of Le Smoking, his dinner jacket, first seen in 1966 and a staple of elegant women’s wardrobes ever since. In his five years as artistic director of Dior Men’s, Jones, among the most gifted and successful fashion designers of his generation, has put tailoring at the centre of his collections, at least partly in homage to Dior and Saint Laurent.

“I love Saint Laurent,” Jones says, “because not only did he make things of beauty but he lived in beauty. He was an exceptional collector, from the best books to the best art. The fact that he had a Goya in his sitting room, on an easel! A terrifying fact to think about. Next to a Mondrian, next to a Picasso! The taste level was second to none. And he and [Saint Laurent’s partner] Pierre Bergé lived in that environment, which is extremely inspiring.”

It’s a wintry November afternoon in London, and the designer and I are sitting in the library of his house, a stunning Brutalist shell of glass, steel and punctured concrete, filled with extraordinary paintings and important furniture, pop-culture curios and exquisite objets d’art — and books, so many books, all beautifully bound: numerous first editions of Virginia Woolf (the Bloomsbury group is a particular passion), Allen Ginsberg (so are the Beats) and countless others.

On the walls: Francis Bacons, Lucian Freuds. There’s a fat Freud pigeon right behind me. The chair I’m perched on? Roger Fry. My eye is drawn to a Renaissance portrait of a stern-faced Italian nobleman. I peer at this individual for a while. “He’s over 500 years old!” I say, somewhat redundantly. “I know!” says Jones. On a table by the door, more recent purchases: Freddie Mercury’s sketch pad and cigarette case. These two will be presents for friends.

Their current owner is wearing a sweatshirt bearing the logo of the Aman hotel in Tokyo. A vintage gold Rolex Daytona, one of a number he owns, is fastened over one cuff: a Jones trademark, in the style of Gianni Agnelli. On arrival, I find him in discussion with the painter Peter Doig, a former collaborator. Jones occupies a prominent position in a rarefied world, surrounded by the great and good of contemporary art, music, film and fashion. But he’s keen to undercut any perceived preciousness. In addition to his Duncan Grant paintings, there are Star Wars figurines and Air Jordans, complete sets of both. He’s drinking a Coke and talking about what he watched on telly last night. A high-low juxtaposition has long distinguished Jones’s approach, to life and to his work.

“If you look at something of beauty, it inspires you,” he says, when I ask about the impulse behind his collecting. “I can stare at a painting, and it’ll give me an idea. I never plan it in any way. If I see something and I like it and I can afford it, I buy it.” Which has long been how discerning menswear shoppers have felt about his own output, from his early days in London, making clothes under his own name, through his period as creative director at Dunhill, for three years from 2008, and on to a hugely influential seven-year stint at Louis Vuitton, from 2011 to 2018. Since then, Dior.

The word “couture” is a freighted one in fashion, and an unusual one in menswear — more often we talk about “bespoke” for the most elevated and expensive men’s clothes — but in the case of Jones’s work for Dior, it fits. He might be famous for his headline-grabbing collaborations — with artists including Kaws, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Raymond Pettibon; fellow designers Shawn Stussy and Donatella Versace; and brands Supreme and Nike — but his work is defined by quality and technique of the highest order. It’s delicate, romantic, lavish but not splashy.

“Some pieces that go into the show are specially made in the atelier for a customer who wants something exceptional, and we have quite a lot of those,” he says. “All the embroidery is done by hand, and [the garments] are hand finished, in the proper couture manner. And then the next level is tailoring, in very high-quality fabrics made specifically for Dior, with techniques used by [Christian] Dior himself. We take all the essences of the first collection and use those references to create what the Dior Men’s look is, and then around that we have a seasonal theme. But the underlying DNA of what we do remains.”

That “first collection” he mentions is Christian Dior’s couture debut, from 1947: the New Look, among the most seismic shifts in the history of fashion. The leopard prints in the new collection are just one of numerous nods to it.

Christian Dior did not design menswear. “But,” says Jones, “he used a lot of men’s fabrics, and English cloth. If I was to pick up [one of his designs] with a blindfold on, I’d think it was a piece of menswear: the construction, the fabrication, the fabric, the handle. The whole structure, really.”

In addition to his role at Dior, Jones designs the womenswear collections for Fendi, having taken over from the late Karl Lagerfeld, in 2020. “Dior is Dior and Fendi is Fendi,” Jones says, decisively. “But when I’m designing tailoring, whoever it’s for, I approach it from a menswear angle. Women seem to like men’s tailoring techniques more, and I can see that from sales [figures]. A good piece of clothing will appeal to anyone.”

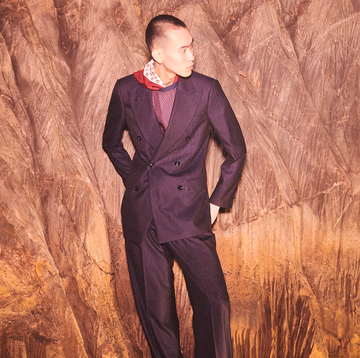

Last June, on a fiercely hot day in Paris, Jones unveiled the spring/summer 2024 collection for Dior Men’s — the clothes that are just going into shops now — with a spectacular show in which models appeared in unison, rising from trapdoors beneath the catwalk.

As ever with Jones — a master of unlocking the “codes” of the various luxury houses at which he has worked, while adding his own combinations — the new collection tips its (many) hats to the past while offering something fresh. The show was entitled “From New Look to New Wave”. References were made not only to the work of Dior and Saint Laurent, specifically his Dior collections from 1959, as seen in a series of sweeping coats, but also to another pair of former Dior womenswear designers: Gianfranco Ferré, on embroidered jackets, and Marc Bohan, in the richness of the textures and embellishments.

Jones was further inspired by women’s silhouettes of the 1920s and 1930s. “That was about looking at womenswear that was very masculine,” he says, “and taking that concept and making it into a menswear look. Basically, taking something that came from menswear and went into womenswear, back into menswear.”

While to the uninitiated some of this may sound arcane, the clothes that result are instantly recognisable as archetypal menswear items — Harrington jackets, polo shirts, crew necks and cardigans, lots of suits — that blend formality and ease, luxury and practicality, in a way that is typical of Jones’s work. As a pioneer, in recent years, of wider, long trousers that pool around the ankles, on this occasion, strides were cropped short.

“I wanted to do something that was a bit directional and new,” he says, “but my brief to myself, so to speak, is always the same: to make the highest quality menswear that you can. There’s a thread throughout the work. I want continuity. I feel like people go to Dior because you know what you’re getting, so we have to make sure it’s there. It’s just common sense and logic.”

Common sense and logic. I have interviewed Jones on multiple occasions over the years, and these are two ideas he returns to repeatedly. He is a great demystifier, refusing to obfuscate or overcomplicate; his clothes are embellished, but his statements aren’t.

“I don’t think about this stuff too much,” he says. “I just do it. I’m very level-headed that way.”

This is to his advantage, because across Dior and Fendi, he designs, at my count, 22 collections each year. Can that be right? “I’ve lost count,” he says. “It seems to be we have about three on the go all the time. But we are organised. I’ve got a core team that works with me across everything and we’re very structured. The planning is done very precisely. It’s not like we’re working all night. We really are strict about our hours because everyone’s got lives. We just get on with it. Because we know what we’re doing and we’ve done it for 20 years. It’s about compartmentalising.” And then he says it again. “Common sense. Logic.”

In fashion circles, Jones’s origin story has achieved the status of folklore. He was born in London, the son of a hydrogeologist father and a librarian mother, and had a peripatetic childhood spent following his dad’s work across Africa, the Caribbean and South America. At 14 he landed back in London. Sparked by magazines such as i-D and The Face, his imagination was fired in the furnace of 1990s London clubland and style culture, a source of frequent and ongoing inspiration. He studied graphic design initially but switched to fashion, completing an MA in menswear under the late Louise Wilson, at Central Saint Martins, crucible of so much British design talent.

His graduate collection was bought, almost in its entirety, by another British designer who would, famously, go on to work at Christian Dior: John Galliano. Lee McQueen was an early friend and mentor. Michael Kopelman, a key figure in streetwear as retailer and founder of the brand Gimme Five, was another. So was Marc Jacobs. Jones disdains the term “streetstyle”, finding it reductive and imprecise, but he has played a central role — perhaps the central role — in the fusion of sportswear and hype culture with high fashion that has driven the explosion of interest, and sales, in the luxury market in recent years.

As ever, Jones deflects praise for any of this, despite the fact that his lightbulb moment came more than two decades ago, when he was still a student. “I just saw that high-low thing and I thought, that’s how people dress, why not make a collection that has both? There was a guy in a pair of jeans with a tailored jacket that was made a bit more punky. I showed that to Louise Wilson, and she was like, ‘I’d like to see this evolve.’

“I wanted to make clothes that my friends would wear,” he says. “Because they were buying Stüssy, old Levi’s, Nikes, Vans, but then a bit of Comme [des Garçons] or Helmut Lang or Margiela, if they could afford it. Or we’d pitch in together and buy something and share it, because otherwise it was too expensive for us.”

The fact that it’s now perfectly commonplace to wear trainers with a suit, for example, when it very much wasn’t before he came along, Jones regards as less a victory for him personally, than a triumph of common sense. “Someone in a really nice suit with a pair of trainers, they look cool,” he says, simply. “If you’re running around all day to meetings, it’s the practical thing to wear. You want clothes that make you feel good about yourself, but also ease is really important. I think about the way people live now, and I want them to feel comfortable in every situation.

“I’m not trying to be famous,” he concludes. “I just like to do my job.”

As well as launching his own label at the beginning of the 2000s, the tyro Jones embarked on a series of collaborations, with brands as varied as Mulberry, Iceberg, Topman, and, most notably, Umbro. He closed Kim Jones in 2008, and joined Dunhill as creative director.

While breathless enthusiasts portray him as a creative visionary, Jones sees himself in more humble terms: a commercial artist working to a brief.

“I don’t design for myself,” he says. “If I did, the label would be called Kim Jones. But it’s not. I work for Dior. I work for Fendi. I design for the house, and for a customer. I look at the brands as an outsider. What does the brand stand for? What are its core values? How should it be developed? I look at the past and pull out what I think is relevant and modern. And get on with it.”

It’s all common sense. “With Dunhill, it had such an amazing art deco archive, so it was about taking things out of that and making a ready-to-wear business. That was interesting.

“With Vuitton, they had a book of 100 trunks and each trunk had its own journey.” He started to base each collection on one of those journeys. “It was easy.” I went to every one of his shows for Vuitton and they were thrilling displays of glamorous wanderlust, conjuring vivid imaginary worlds inspired by the designer’s travels. The idea that all this was “easy” to pull off makes me snort. But Jones remains as straight-faced as the man in the 15th-century portrait on his wall.

“With Dior,” he continues, “there’s so much history: you go into the archive, you pull out five pieces, you can make a whole collection. The workmanship, the pattern cutting, the ‘make’, it’s all there. And we’re slowly, chronologically, working our way through the archive. I just thought that would be the most logical way to start.”

Unusually, then, for a fashion designer, he undersells himself. He must be pleased with how far he’s come. “I’m not reflective. I don’t think about it. I’m on to the next thing.”

Would he ever consider bringing the Kim Jones label back? “I don’t think the world needs another collection right now!”

Just as likely, he might decide to leave fashion altogether. “I don’t think fashion is everything,” he says. “If I get bored, I’ll stop and do something else. One morning I might wake up and say, ‘I don’t want to do this any more.’ I might want to go and make a film. My hobbies are very different to fashion. I might want to do conservation full time.”

Beyond art and books and design, the natural world is his abiding passion, the legacy of his far-flung childhood. As well as the London house, Jones also owns an 18th-century rectory in Sussex, equally stuffed with rare treasures but decidedly more bucolic. He dedicates much free time to conservation projects around the world, putting his money towards saving rare monkeys in Southeast Asia, endangered parrots in New Zealand… So why doesn’t he do it, then? Jack it all in and spend more time in the wild?

“I haven’t achieved my best yet,” he says, before letting slip the only acknowledgement of his own prodigious talent I manage to extract from this resolutely no-nonsense man in an hour of trying, really quite hard, to get him to crack. “But I think I’m warming up to it.” All those with an interest in style and design and exceptional men’s clothes will be pleased to hear it.