If there’s a definitive item of men’s clothing right now, it’s probably the humble chore jacket. Invented by the French to outfit 19th-century railway workers, the chore has become ubiquitous among a more contemporary set of earners: architects, designers, creative directors, chefs (who used to be creative directors) and Monty Don on the TV, pottering around the garden in Blundstones and a ragged bleu de travail, a golden retriever weaving between his feet. It’s the perfect hybrid garment — a bit of blazer and a bit of outerwear, with loads of pockets and a simple silhouette that can be manufactured in wool, cotton, denim, canvas or suede. It epitomises the style of clothing known as workwear. You don’t have to wear it to work in. But you can, especially in our unbuttoned age of WFH. And even if you are desk-bound in a corporate setting, there’s something about dressing like a Norfolk cockle picker or a Nottingham carpenter that seems to holds an insatiable appeal for many stylish British men.

Adam Cameron founded The Workers Club in 2015 with his wife Charlotte. After years spent as head of design at Dunhill, Cameron was tired of the pressures of working for a British luxury heritage brand, and he had the experience and knowledge of how he might make something for himself and people like him. “The Workers Club was in gestation for my whole time there,” says Cameron, “so around 15 years. Charlotte and I went to college together, and we always spoke about having our own business, which sounds very twee. We wanted to live in the countryside and drive a Land Rover and have chickens… That was the dream. It was always an itch that I wanted to scratch. We wanted to create something that was pure and uncompromised, I suppose. Maybe it was a bit self-indulgent, but I wanted to spend as much time as I wanted and could on it. It’s really well-made and really well thought-out, because we spend the time and energy on every item.”

TWC first launched online on Mr Porter and opened its first shop on Chiltern Street, in Marylebone, London, in 2023. It makes heavy-duty waxed jackets, work shirts and relaxed trousers that don’t conform to the rapid-fire seasonality of contemporary fashion: items of clothing that feel tactile and expensive and like they can handle a bit of a beating. “The term ‘workwear’ doesn’t cover all bases,” says Cameron, “but if I were to sum it up, it’s functional clothing that does a job and isn’t fussy. All the details serve a purpose. It is a very British thing; it’s the nature of our history. I guess it’s why people in Japan love and have this very fixed idea of us and our clothes, as functional and unglamorous — although, I like to think we’re quite modern… put us down as modernist.”

Thanks to the United Kingdom’s role in industrialisation and garment manufacturing, workwear is one of our strong suits. Designers like Margaret Howell and Nigel Cabourn have turned stark, Northern work clothing and heavily detailed British militaria with Scandinavian and Japanese inflections into global, luxury businesses, alongside the more established names like Burberry, Barbour and Belstaff. And there are plenty of other small-batch independents creating beautiful clothes influenced by their more immediate surroundings.

“I was always inspired by my father and his brothers,” says David Keyte, the founder of Universal Works. “My dad was a baker; my uncles, a carpenter and a house builder — practical workers. I always loved their working garments. The practical use drove purposeful, hard-wearing jackets and pants they wore daily.

“But I also loved those Fridays and Saturday nights when they donned their ‘fancy’ suits and got dressed up for a night out. For me, the chore jacket my dad wore to work, with useful pockets and a loose but practical fit, was a thing of beauty, which is why we call our version of the chore jacket or work jacket ‘The Bakers Jacket’, and it seems to have become almost a generic term for this style now.”

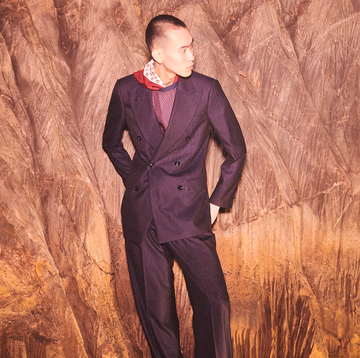

Universal Works was founded in Nottingham in 2009. Keyte started out designing clothes at his kitchen table and now has London shops in Soho and Coal Drops Yard in King’s Cross, a flagship in Nottingham, and partnered stores in Birmingham and Berlin. The brand makes smart pleated trousers with elasticated waists, waterproof parkas, and work jackets in technical Japanese fabric and Scottish tweeds. You can buy the pleated track pants in corduroy or brushed Nebraska cotton and pair them with a matching Bakers jacket for the weekend, or the three-button blazer in the same material for a wedding (Keyte gets sent lots of photos of men getting married in UW).

“Workwear to most people under the age of 40 is a cheap suit, as we all became office workers,” says Keyte. “Not blue-collar chore coats. Then we all became work-from-home, so ‘workwear’ is a sweatshirt and tracksuit trousers or shorts. So, I think the term has lost meaning, apart from for us in the industry or fans of the style. But while we at UW are inspired by traditional workwear, we are also inspired by Savile Row tailoring, military uniforms, Japanese kimonos, Indian kurtas — all of these in some ways are ‘work’ wear. What UW is about is totally contemporary and for now, so to call it workwear is definitely too vague… but it’s sort of OK, too.”

Traditional tailoring, as you’ve probably heard, is in flux. As much as a beautiful suit will always hold a certain allure, few of us need to wear one to the office anymore. Workwear presents itself as a middle ground: smart, but not over the top, useful, versatile, easy to wear. Also, clothes with an interesting backstory.

The onset of working from home didn’t usher in an age of soft, shapeless tracksuits like many predicted, but it did change things. As many of the people I speak to attest, men quite like to wear clothes that are functional, durable, and not prone to the caprices of the dreaded trend cycle.

Street-fashion photographer Bill Cunningham cutting about Manhattan for decades with not much more than a bike, a Nikon and a blue chore coat; Picasso in paint-splattered brushed cotton and striped trousers, made by the Italian tailor Michel Sapone; chef-restaurateur Fergus Henderson’s butcher-stripe suits that look, in the best way possible, like they’ve lived through a lifetime of service. These are items that are intertwined with the wearer’s work and life: “I am serious… but not too serious.”

Sign up to the Esquire Shops newsletter. Each week, we'll be directing you towards some of the best menswear deals happening right now, alongside style advice, trend reports, grooming tips and product recommendations from the most tasteful people we know.

There’s also an element of fantasy. A lot of jobs are about meetings and emails, and emails about meetings. There aren’t too many trawlermen left, but a heavy knit or a waxed-cotton smock allows its wearer to partake in the myth of it all. The American fashion-bro set has even coined a term for it: “Blue-collar stolen valour”. You’re borrowing a bit of the magic, and the masculinity.

“We have been designing and manufacturing workwear since 1898,” says Sophie Miller, who heads up design at Yarmouth Oilskins on the Norfolk coast. “This year is our 125th anniversary, so throughout those years we have a rich history of making functional clothes, whose design is driven by practicality.”

The clothes that Miller creates have pleasingly straightforward names like the Engineer jacket, the Work trousers, or the Maritime shirt. “Many of the core pieces in our collection are direct versions of styles we made 60-plus years ago,” she says. “‘Workwear’ is a confusingly broad term; a Google search will bring up anything from hi-vis construction wear to machine-washable synthetic office suits. However, it is a signpost to the clothes we make.”

“I saw a sign outside a bar the other day that read, ‘No streetwear’,’” says Will Brown, who, along with his wife Marie, founded Old Town in 1992. The pair now sell their clothes online and at their appointment-only shop in Holt, Norfolk. “What does that mean? Fashion is a deeply conservative business that still uses terms such as ‘formal’ and ‘casual.”’ Brown likes to say that Old Town lets “the construction influence the look”.

“Many of our customers still wear our clothes for practical work,” adds Miller, of Yarmouth Oilskins. “We sell to artisan makers, potters, chefs and gardeners, who value the durability and resilience of our pieces. We also sell to many who just love the look of the clothes we make, and identify with our approach to British-made, slow fashion, made as sustainably as we practically can.”

On an industrial-grey day in Walthamstow, north London, I eventually find the entrance to Blackhorse Lane Ateliers, London’s only denim factory. Inside, it looks like a clean film set of manufacturing: men and women carefully sewing, cutting and priming fabric beneath strip lighting. More surprisingly, a small team of chefs and porters works busily in a kitchen off to one side, in a venture called SlowBurn that sees the entire factory space turned into a functioning restaurant on weekends.

Bilgehan “Han” Ates is BLA’s founder; a second-generation Londoner of Turkish and Kurdish ancestry, he has a full head of curly, grey-flecked hair and a friendly face. He set up the denim factory in 2016, after a roundabout journey spanning 25 years. Initially, he started a textile business, making ready-to-wear tailoring in the same 1920s factory that now houses BLA, employing 110 people and producing 5,500 pieces a week, eventually scaling up in Turkey and then China. “By around 2009, I was fed up with everything,” says Ates, “travelling and travelling, so I sold to my business partner and opened a restaurant in Stoke Newington. I’d lived in the area for 22 years, and I didn’t know any of my neighbours. I was travelling so much and didn’t feel connected.”

Within a year, his restaurant had become a fixture of the neighbourhood, hosting birthdays, weddings and anniversaries. “I became part of that community, which was a cool feeling.” Along with the restaurant, Ates was studying psychotherapy and, during one fateful session, his course teacher asked him, he recalls, “how I define myself as an artist in my everyday life. I had this amazing restaurant, but artistically I couldn’t say I was in the driving seat. I decided to finish the restaurant, and to come back to what I know best. But I wanted to do things differently. I was never happy with my own denim. I thought, ‘I’m going to make jeans in London!’ So I did.”

BLA is renowned for the quality of its output; Ates proudly compares the grade of the stitching and seam-work of his denim against the unfinished edges of jeans made by far better known brands. It offers a ready-to-wear line, along with a made-to-measure service that begins at £475 for jeans and £625 for jackets. I’m whisked around the factory and introduced to various members of the team, including Leanne Jae Callender, who looks after the company’s denim lab and laundry process. She shows me a pair of high-tech-looking machines by the Italian company Tonello, a giant washing machine and a laser and printer that allow them to both create more elaborate designs and washes; then a space where graduates and young designers can experiment without crippling costs.

“We’re the only denim factory in London,” says Callender, “so we want to help and to offer up some opportunities to the next generation — to make the community healthier where we can.”

Back at the table, Ates recalls an event he attended recently at London Design Week. “I was in this room, and I looked around and saw that everyone in the room was wearing denim and a chore coat,” he says, voice rising and hands gesticulating. “That is how the workers dress today. We don’t need to be miners to wear denim anymore.

“It’s our uniform, isn’t it?”

Sign up to the Esquire Shops newsletter. Each week, we'll be directing you towards some of the best menswear deals happening right now, alongside style advice, trend reports, grooming tips and product recommendations from the most tasteful people we know.