Looking back, it’s alarming to think we weren’t more alarmed. It was the afternoon of the 23rd of February and members of the fashion pack, in Milan for the A/W’20 shows, had retreated to Trattoria Torre di Pisa in the Brera district of the city. In the previous few days, cases of Covid-19 had been recorded in remote areas of northern Italy, but the city was still ‘open’ and brands continued to show. Italy wouldn’t go into formal lockdown for another fortnight.

Early that morning, Giorgio Armani had announced that he would be cancelling his live show, but other heavyweights, such as Hugo Boss and Dolce & Gabbana, persisted. The mood on the streets, and in the restaurant, was a little confused, but not panicked. At one quiet corner table, Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons dined with colleagues, likely discussing their next moves having just a few hours before announcing that the latter would be joining the former at the helm of the eponymous brand. Despite its nebulousness, the virus had still managed to overshadow the juiciest industry news in years.

I was headed home that evening, but for those bound for Paris and the culmination of the A/W’20 shows, it was unclear how it would all play out. Though the French prefer to think of themselves as setting trends, rather than following them, if the Milanese shows were being cancelled then surely the Parisians would follow suit. And if not, would attendees be safe? Most pertinent of all, what did all this mean for the long-term health of the industry more widely?

According to the State of Fashion 2020 report, first published in late 2019 but amended in the midst of the global pandemic, the average market capitalisation of fashion and luxury brands dropped by almost 40 per cent between the start of January and the end of March. The report, produced by The Business of Fashion and McKinsey & Company, also states that, compared to last year, fashion brands (apparel and footwear) will see a revenue contraction of up to 30 per cent in 2020, while luxury brands (high fashion, luxury watches, fragrance, jewellery etc.) could shrink by close to 40 per cent. Over the next 12-18 months, a “large number of global fashion companies” will be bankrupt, it says. The fashion industry, faced with declining sales and shifting consumer habits and hard-to-predict tastes, was already at “red alert”. Coronavirus may just be the death knell for many involved.

Pretty bleak, then. And yet, we persist.

This weekend, London Fashion Week Men’s (LFWM) will go ahead as planned. Well, not as planned, no as named - it is now just London Fashion Week - but as scheduled. There won’t be any actual physical fashion shows to attend, nor any events of any kind, really. There will be no air kisses or hastily gulped espressos. There will be no bloggers, walking back and forth in the hope of attracting street style photographers. There might not even be any clothes.

Guests will be invited to log-in rather than queue up, and once they’re in it’s not clear what they’ll be presented with. However, an April statement from the British Fashion Council, organisers of LFW, suggested there will be interviews, podcasts, designer diaries, webinars and digital showrooms, among other things. And it will be gender neutral, and open to the public for the first time. Much is in flux, but one thing seems certain: the nature of seasonal fashion and how it is unveiled will never be the same again.

“The Covid-19 pandemic is hitting the fashion industry from every angle and severely impacting all of the global fashion capitals,” stated another late-May press release from the BFC and its Stateside equivalent, the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), “and while there is no immediate end in sight, there is an opportunity to rethink and reset the way in which we all work and show our collections.”

It goes on to urge designers to limit their output to just two collections a year, which would not only put the kibosh on the culture of consumption the industry promotes, but allow creativity to come to the fore once again. “A slower pace also offers an opportunity to reduce the stress levels of designers and their teams,” it states, “which in turn will have a positive effect on the overall wellbeing of the industry.”

(This concept of ‘punishment’ is not new. From what I understand, the June shows aren’t so bad, but the January ones can be a logistical nightmare. Pre-production happens throughout the Christmas period, which is a slow time in general, but then for the fortnight before the show, everyone is on holiday. “When you have to show a collection in January, you have to make sure you’re really organised,” explains Bianca Saunders, one of LFW’s clutch of young British designers, “because a lot of things shut down [over Christmas and New Year] so you don’t have access to materials. And if you want to change ideas [at the last minute], you can never do that.”)

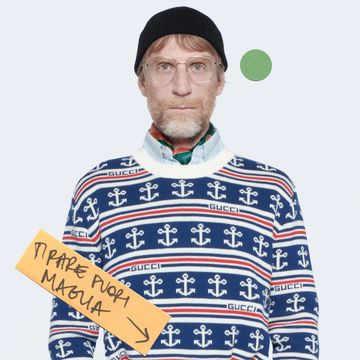

A few days after the BFC/CFDA statement, on Instagram, Gucci’s creative director, Alessandro Michele, echoed the excoriation in more floral verse, explaining that in response to the industry’s effect on the environment, the brand would henceforth show just two ‘seasonless’ collections every year. It’s an especially poignant stance when you consider that, had Covid not derailed the plan, the brand’s ‘cruise’ (high-summer) collection would have been shown at a one-off event in San Francisco in May.

“So much haughtiness made us lose our sisterhood with the butterflies, the flowers, the trees and the roots,” Michele artfully explained, “So much outrageous greed made us lose the harmony and the care, the connection and the belonging.”

In the recent past, feted designers such Dries Van Noten and Marc Jacobs have mirrored the BFC and CFDA’s sentiment by speaking out against the churn of the industry and the culture of consumption it seems to espouse. Many, however, such as Patrick Grant of E Tautz, have held the view for some time, and even based their businesses on it.

“The idea of a return to quality and a return to the value of product – in our brand that’s never gone away,” he explains. “[E Tautz has] always been about trying to sell you something that’s beautifully designed, incredibly high quality and has enduring value. If you’re a brand where that wasn’t part of your proposition then you’re going to have to start thinking differently.”

This weekend, E Tautz, one of the mainstays of LFW and latterly, one its biggest draws, will be unveiling a digital presentation that has found a way to “tell the story of this collection, without being able to physically make or photograph garments." Grant is taciturn, reluctant to reveal too much, but he concedes that the production uses references from a “couple of different artists” and was created with the help of Photoshop-savvy students at John Moore’s University in Liverpool. Instead of a collection of clothes, then, E Tautz will be presenting a… vibe.

Grant, who also helms Savile Row tailor Norton & Sons and the altruistic, Blackburn-based Community Clothing, is known for his vocal championing of craftsmanship, transparency, ethical production and the general outlook of quality over quantity. But would the repurposing of a physical show into an intangible, digital presentation not be at odds with his need to illustrate the intricacies of the clothing itself? The way it’s stitched together, the way it hangs on the body, the way it moves when you walk. The point, at least until very recently, of holding a fashion show in the first place.

“For a brand like us, where we don’t flip flop from one thing to another on a seasonal basis,” he says, “there is a continuity in the way our clothes look and feel.” Buyers that would normally attend the show on behalf of potential stockists will receive a different, more detailed presentation, so Grant is confident that sales of the new collection won’t be vastly affected – around half of what they should be, he says, which seems like a lot to me, but I don’t hear much distress in his voice – and the catwalk stuff only represents around 30 per cent of the brand’s output, anyway.

“There’s been so many years of excessive spending in the fashion industry,” says Grant “all about just buying attention. And there hasn’t been that much attention on the clothes anyway. The big brands aren’t selling clothes, they’re just selling an idea. And I think our customers like our clothes and for them the peripheral stuff is of less importance than the clothes that are hanging in the store.”

Grant seems to relish this opportunity to push the reset button. He savours a situation in which budgets matter less and designers are forced to be even more creative, proudly telling me that “London’s design scene has always got by on a shitload of creativity and not very much money.”

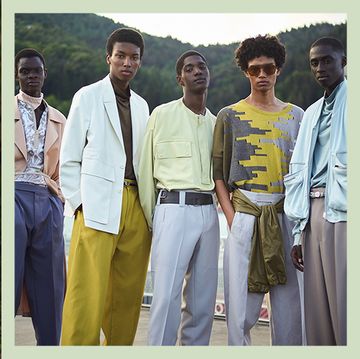

Maybe, as the BFC and CFDA allude, designers have long needed a break. Saunders, who is the only full-time employee of her brand, is certainly relishing the opportunity to catch up on all the little things that hover on the to-do list. This weekend, instead of a runway show, she is releasing a zine. The images within were shot over a year ago, but only now has Saunders had the time to pull everything into a publishable state.

“It’s weird, but I feel like this whole lockdown situation has had a silver lining,” she tells me over the phone. “I have achieved a lot over the past few months. I’ve been able to really go over the things the business didn’t have, rethink some strategies and take a break. Creatively, I had more time to think about my ideas, create plan for the rest of the year, and I guess set new goals.”

Saunders is now planning to show her S/S’21 collection in September, as will many others, we can assume. But we can’t be sure. That is to say, there’s no guarantee that by that point it will be possible to host an event that showcases clothes. (Rest assured there’ll be plenty of cool stuff, though. On a recent call to Virgil Abloh, the Louis Vuitton menswear designer told me that lockdown had only made his ideas bigger, and I should “watch this space”.)

The hope of this article was to explain what’s happening now and what could happen in the future, but from where I’m standing, it seems impossible to predict. Gucci and Saint Laurent have said that they will announce their own respective unique calendars in due course, so it’s fair to assume that other industry heavyweights won’t want to be left out of the vanguard.

As this weekend’s digital program proves, the void left by a lack of physical fashion can quickly be filled, or at least temporarily papered over, with tech. Perhaps a systemic dismantling of the fashion show tradition (which seems on the cards) will hasten the arrival of digital and ‘intangible’ clothing, the kind of thing created by Dutch ‘digital fashion house’ The Fabricant, which sold a one of a kind pixel-based ‘garment’ for £7,800 last spring (below).

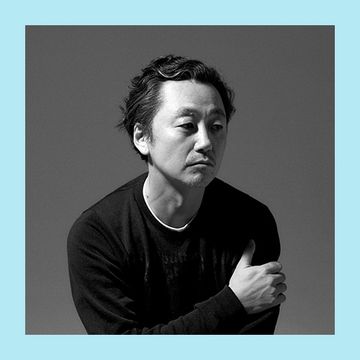

“I'm excited to see how these ideas mature and how some of the bigger holding companies and groups go about initiating these ideas moving forward,” Samuel Ross, founder of the barnstorming British streetwear brand A Cold Wall tells me over Zoom, “because this idea of tangible fashion… the supply chain is just far too complex for it to be ever sustainable, so it needs to move into intangible format to a certain degree, and how intangibles work with fixed tangible garment are definitely of interest.”

Designers such as Ross will likely view this time of reckoning as a chance for the fashion industry to evolve into a new phase of digital relevance. Whereas designers that follow the Patrick Grant school of thought see this all as an opportunity cast off the bells and whistles and strip it all back to the core principles of craftsmanship and value. Both viewpoints are valid, and both suggest a time in the near future where the consumer gets exactly what they want, rather than what they feel they need.

Either way, the new age of garms is beginning.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts