What makes a woodcutter pivot to working in the wool and cashmere industry?

“It’s really satisfying knowing that you’re part of a team that produces such luxurious products,” says David Garrow, chargehand at Johnstons of Elgin.

He’s been working at the 226-year-old Scottish knitwear brand since 1990, employed within the dyehouse after moving to the area from Aviemore, an hour's drive away.

After four years learning about the cashmere and lambswool dyeing process, Garrow became part of the team overseeing the wool store. There he learned about the material in its raw state, and the path it takes from start to finish.

“The industry was alien to me,” he says. “But every day is a learning day.”

Johnstons of Elgin remains both family-owned and less famous than some other Scottish knitwear juggernauts – though it can be hard to see why.

The brand was awarded a Royal Warrant in 2013 by the then-Prince of Wales, has been designing the Balmoral Tartan since Prince Albert first commissioned it, creates wool and cashmere goods for some of the luxury world's biggest fashion houses – it isn't allowed to publicise who, but it's not a hard guessing game when you see the prints and colours within the factory – and has dressed the likes of James Norton, Mads Mikkelsen and Chiwetel Ejiofor.

In September, the fashion industry news site Drapers reported that Johnstons of Elgin had 'record levels' of sales, growing 26% on the previous year from £66.4m to £83.5m.

David Garow is not the only member of his family to have worked for the brand. His wife held a part-time position when their children were young, and his younger son, Pete, spent his summers between university terms in the finishing department. His eldest, David Jr, worked as a lab technician and a shift dyer before pursuing a career in engineering. Nine years later, he returned and is now employed in the continuous improvement department, where he also mentors young people through the brand’s relationship with social mobility charity Career Ready.

Garrow Sr notes how “it’s nice to know your family is close” – a sentiment that’s also influenced his eldest son.

“[Johnstons of Elgin] has always been prevalent in my life because Dad had worked there for as long as I can remember, I always felt drawn to work in the business because of that,” he says. “The industry itself wasn't pulling me in. I had a personal connection that made it interesting to me.”

The brand’s birthplace and long-standing mill is in, unsurprisingly, Elgin; a historic town on the north coast of Scotland filled with picture-perfect architecture and a rich heritage in whisky distilling and knitwear production.

Before I'm greeted by the team, the mill cat (who has no name other than 'Mill Cat') prowls forward. She takes a seat next to the front door, where she has perfected the art of luring prospective customers over for a stroke and watching them enter.

Soon after, I'm met by brand CEO Chris Gaffney, who directs me to the start of the tour via the brand’s archives, which veer off from a hallway filled with portraits of the former Johnstons, and more recently, Harrisons, who married into the family and took the helm in the 1920s. Jenny Urquhart, a fourth generation Harrison follows in the footsteps of her father, grandfather and great-grandfather, as chairman.

Johnstons of Elgin’s history starts in 1797, when Alexander Johnston established the Newmill in Elgin on the banks of the River Lossie. Previously a tobacco mill, Johnston phased out its original products in favour of the warming fibre, travelling the length of Scotland to spread the news of his entrepreneurial endeavour. By 1811, the site was fully vertical – handling the process of dyeing, spinning, weaving and finishing in one place – and remains the only one of its kind in Scotland today.

Gaffney, much like his employees, is tied to the brand not just in employment but through geographical heritage: his birthplace of Hawick is the site of another Johnstons of Elgin mill (specifically for knitting), and Elgin was where he spent his childhood.

During the tour, facts on the brand’s history, craftsmanship values and fibre-to-yarn processes naturally pour out of him like a dram of Macallan, narrated with a soft Scottish cadence that’s as comforting as the brand’s cashmere blankets.

The mill workers also share that calming expertise as they go about the thirty processes involved in the creation of their knitwear, nodding in recognition as I’m hypnotised by the monotonous movements of the machinery. Maybe it was with the help of the required earbuds, but I found the noisy environment oddly relaxing.

I wasn't alone. Smiles are aplenty, and from subtly eavesdropping, I noticed that co-worker chat goes far deeper than water-cooler small talk about the latest buzzy Netflix show. That compassion for one another trickles down to the garments; one employee who hand-knits the baby clothes and booties hugs every piece she finishes.

“In a business where quality is vital, it is important that our people feel a connection to the company and the product,” Gaffney says. “Being part of a real family that works in the mill, or feeling part of our broader Johnstons 'family', underpins a culture of high quality and care for the textiles we make.”

Johnstons of Elgin has always looked to its surroundings for its employment force, much in the way it looks to its neighbouring river's water as a source to wash the raw fibres.

“It isn’t just important to have locals and families working for our business, it is our purpose, our reason for being,” continues Gaffney. “The family that owns Johnstons see the company as custodians of the business, with the aim of always passing it on to the next generation in a better situation than when they inherited it, and creating economic activity in our communities in Scotland is at the heart of that.”

So how does that ensure another 226 years of business?

Growth is a term that comes naturally to entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, who see the world with dollar signs and themselves as ‘innovators’. Their capitalist view has sadly become a universal measure of success, and many brands are scrambling to scale before even fully understanding what they can first offer. But Gaffney questions what the point of expanding is if what first made your business special is lost.

“If there are opportunities to expand in areas that we have real expertise in and can create local employment, then we will take them, but we don’t want to be a massive international brand,” he says.

“One of the old adages about luxury was that it was based upon scarcity, being 'in the know' and finding special, unique brands. That’s perhaps not as common as it was, due to the rise of the luxury mega-brands, but it’s certainly where we position ourselves. Everything we make comes from our mills. We aren’t a brand that sources product, we make it, and that puts a natural and very comfortable cap on our output.”

Knitwear, and cashmere especially, is tested by touch: if you put it on and don’t instantly feel warmed and wintery, like the first sip of mulled wine at a Christmas market, then it hasn’t done its job. This feeling is rarely achievable with anything other than natural fibres, which, when combined with the cost of transporting them from the other side of the world, doesn’t come cheap.

Johnstons of Elgin source their merino wool from Australia, and their cashmere comes from China, Mongolia and Afghanistan, all quality-checked at four separate points before it's dyed. While the brand is passionate about the livelihood of its home-soil employees, that also extends to its partners oversees. Johnstons of Elgin is one of the three founding members of the SFA Cashmere Standard, a non-profit formed in 2015 to work with the cashmere supply chain to ensure grassland is restored, animals are well looked-after and herders have a secure livelihood. This, alongside its recent B Corp status, allows for long-lasting, sustainable production.

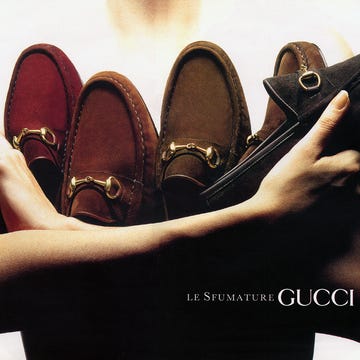

That durable mindset is prevalent in the design department, where timeless silhouettes are favoured over fleeting trends. That isn’t to say the pieces play it safe or lack pigmentation – their autumn/winter ’23 collection is packed with reds ranging from tomato to a festive holly, interspersed with earthy browns and deep-sea blues, all of which could be attributed to its natural surroundings. There’s tartan, of course, in non-garish scarf form, as well as different types of check.

“I always get the sense that people are proud of what we do,” says Gaffney, relaying his favourite aspect of the Johnstons of Elgin workforce. “They want to give their best and try and help each other out.”

Garrow Jr agrees. “What I find interesting is that not only are the relationships across the company strong, but within departments, you have micro-communities of people who work closely together… Sometimes people working closely develop friendships which can extend outside of work. Other times it can be communities formed through common experience. A good example is that first-time parents can gravitate towards each other for support. I’ve experienced this myself when my daughter was born, I felt that opened new opportunities to speak to new people that previously I may not have been able to connect with in a meaningful way.”

Comfort comes from a cashmere sweater. It also comes from building and nurturing the community that makes it.