Paul Pogba wanted a Gucci jacket. It was the eve of France’s 2018 World Cup semi-final, the biggest match of the Manchester United midfielder’s career, against Belgium in Saint Petersburg.

He’d heard from Barcelona’s Samuel Umtiti, who’d heard from Manchester City’s Benjamin Mendy, that there was a kid in London who could source whatever rare designer item you were looking for: trainers, streetwear, luggage, Gucci jackets, anything. All you had to do was Whatsapp him.

So the most famous footballer in France picked up his phone and dialled the number, and a 17-year-old from Finchley answered immediately.

According to his Instagram page (follower count: 117,000), Sam Morgan, aka @SM_Creps, is a ‘Personal Shopper’ supplying ‘limited/sold out sneakers & clothes.’ Neatly-arranged, grail-worthy streetwear spreads throughout his grid like a modern teenager’s wildest dream, all of it for sale. It was Pogba who first nicknamed him ‘The Plug’ (Urban Dictionary definition: “Someone who is a resource for obtaining something valuable, that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to obtain.”) and the name stuck.

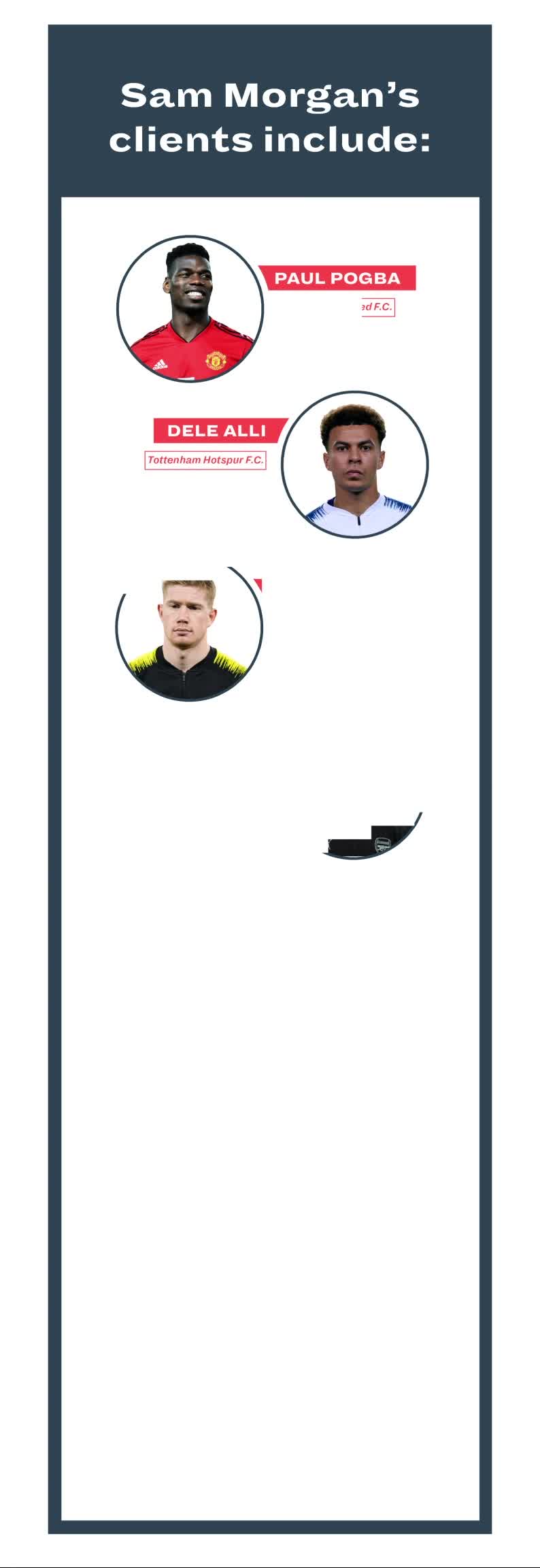

It took Sam nearly two years to make an initial £3,000 profit, before his business really took off. His football breakthrough came when he managed to get in touch with Arsenal U23 player Cohen Bramall, and then West Ham’s Declan Rice, selling Adidas Yeezy Boost 350’s to both. Word spread amongst the young players of the Premier League. Reiss Nelson, now of Hoffenheim in the Bundesliga, reached out, then Chelsea’s Tammy Abraham and Liverpool’s Trent Alexander-Arnold. A football changing room is a small universe. Soon first team players were calling: Alexandre Lacazette, Mesut Ozil, Wilfried Zaha. He met Kevin De Bruyne playing Fortnite online, football’s other favourite pastime. He plays regularly against Dele Alli, too. “I’m better than him, but he won’t want to hear that!” Sam tells me, chuckling.

“I started off just selling shoes every day on Ebay, Depop and Facebook”, he says. “Now I know people in the sneaker and clothes worlds in America, France, Italy, Germany, Poland - I’ve already said America, right? - everywhere in Europe. I know if something is coming out in a certain country, and I can sort it.”

Sam lives on the outskirts of North London, where the city breaks into suburbia with wide-open skies, jumbled allotments and Hondas parked outside detached houses, with his mum Emma, dad Grant - who doubles as his manager - two elder brothers and a twin sister. The Morgan house is neat and pale. A small dog buzzes between rooms. Outside is a garden with long grass and two football goals, knocked askew by wind and rain.

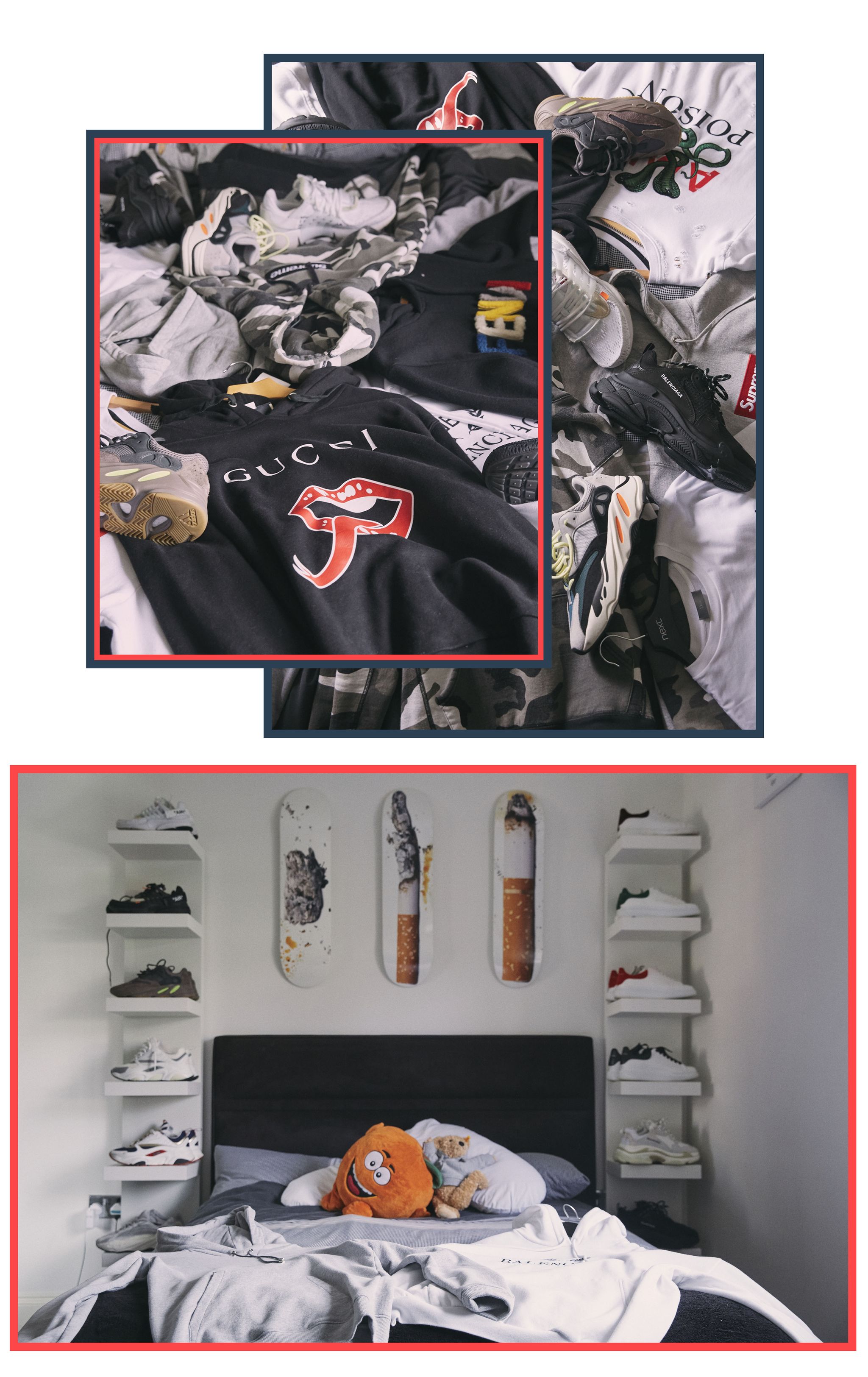

In person Sam is, like the photos where he poses next to the best players in the world, skinny and smiley, younger-looking than 17. He’s wearing an oversized Amiri logo hoody and a pair of the brand’s signature, chaotically ripped jeans (Amiri, the LA-based streetwear label where denim goes for £900+ and sweats for £750+, is a favourite of Pogba’s and many of his other high-profile clients. (Sam introduced Tottenham’s Erik Lamela to their jeans and now he “won’t wear anything else".) As we chat in his bedroom - Apple Air Pods on the side table, triptych of rare Supreme skateboards hung above his bed, the air tinged slightly bitter by supermarket deodorant - his eyes flit frequently to his bedroom window, ears straining for phantom rings of the doorbell and a courier with a fresh delivery. He doesn’t keep any stock in the house during A-levels (he’s studying business and psychology) because it's “too much stress.” Normally, the doorbell rings a lot.

It’s hard to know exactly how much Sam is making because he doesn’t want to talk about it. Both he and his father, Grant, assures me it’s a “lot”. By the looks of his client list and personal wardrobe, I’m inclined to believe them. By the time he’d woken up at 10AM on this dreary day off college, Sam had already received orders from Arsenal’s Mesut Ozil and several players from France’s Ligue 1 that, without detailing exact numbers, amount to a couple of months-worth of a very good yearly salary.

His peers thought it was weird at first, but now it’s cool: “I know who my real friends are,” he insists. The Instagram comments are positive - it's all people who want to know how he does it, though he’ll never tell. He doesn’t know what he’ll be doing in five years; he didn’t imagine it would go this far. “I do know that I’ll always be self-employed,” he says, almost staring through me. “I’ll never work for anyone else.”

The global clothing resale market is a secret behemoth that’s growing rapidly. A 2018 report by Thred Up valued it at $20bn, estimating sales of $41bn by 2022, a growth rate of 15% annually, compared to just 2% for the traditional retail sector. Agile start-ups that specialise in connecting engaged customers with hard-to-find trainers and clothing like StockX, Grailed and Goat - a sneaker authentication and marketplace platform that recently received a highly-publicised $100 million investment from Foot Locker - are re-defining the way people, in particularly young men with disposable income and an increasing desire for limited, branded items, shop.

According to Matt Powell, Senior Industry Advisor for Sports at NPD market research and an expert in the athletic goods industry, this new-wave resale gold rush presents an opportunity for unprecedented “profiteering.”

“There is,” Powell adds, “big money to be made by re-selling.”

“You like those, don’t you?” Sam says, noticing me eyeing up a pair of black Nike x Off-White Air Prestos that I fruitlessly, embarrassingly, entered three raffles to try and purchase back in 2017.

“I’d never pay more than retail for something like those,” he says matter-of-factly, turning away from them.

This much I can tell about Sam's business empire: there’s a guy who sorts out the trainers. In fact, there are several. One for Yeezy, one for the rare Nike and Off-White. “They have all my cards and packaging.” There’s also a full-time employee who looks after the day-to-day orders while Sam focuses on the “VIP” clients.

Dele Alli often visits the Morgan house to pick out his new season outfits. “He’s just bought his summer things. I could have brought 50 items for him to choose from, and I know he’d have bought 30 of them, but I brought 200 instead.

“I know a couple of rappers, Fredo and Dave.” he continues. “They’re both friends with Drake, so I’d like to talk to him. I’m also in contact with Conor McGregor, so I’m hoping to sort some stuff out for him soon.”

Players will try everything on in the lounge, clothes and trainers laid out on the floor, a mirror in the corner. Alli likes Amiri jeans, Dior trainers and Goyard wallets.

“I wanted the Off-White x Nike Air Force 1’s and the Off-White x Converse Chuck Taylors,” West Ham’s Congolese fullback Arthur Masuaku tells me, “and two hours later he had them.

“He’s a nice guy, he’s friendly. Even though he’s young, I like what he’s doing. If I want something, I text him and he’ll have it quickly. He knows how to run his business.”

The average Premier League salary is now more than £50,000 per week. That level of wealth, combined with a player culture that favours a peculiar mix of ostentation and conforming to the status quo, means footballers are the perfect client for rare, expensive stuff that makes them look just like their peers. Amiri, Balenciaga, Saint Laurent, Off-White, Givenchy, Gucci, Virgil Abloh’s Louis Vuitton collections, Nike, Alexander McQueen, Palm Angels, Supreme and Heron Preston are their staple brands.

“I think footballers like me because I’m young and I put a lot of effort in,” Sam says, sat on his bed. “I think they like the fact I’ll work hard for them.”

Pogba likes to set him “little challenges” - requests for rare luggage, long-sold-out sneakers or designer children’s clothing. He’s sprinted into Camden Market to find a PS4 charging cable for Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, who sent him the request two hours before leaving on Arsenal’s pre-season tour to Singapore. A player from West Ham recently approached him, “just to introduce himself.” Nathaniel Chalobah, the Watford midfielder, contacted Sam recently. “I hear good things about you, I hear you’re The Plug.” He said by way of an introduction, before setting Sam the task of hunting down a Louis Vuitton bag from the Parisian brand’s 2015 collection. “I’ve found one from America. I’m hoping it’s brand new, if it’s not I’ll just keep going until I do.”

“Once they [the footballers] see you with the big dogs, the others take notice because they know you’re serious. Plus, being the only personal shopper in England with a blue tick helps. It means you’re serious. Not that that blue tick means anything in the actual outside world, but in terms of business it helps a lot.

“There are a lot of people in this world who wake up one morning and say they want to be a millionaire, but they don’t have the fight or drive to get to where they want to get to.

“Do you support a football team?” he asks, abruptly ending the monologue. Tottenham, I reply.

“I was a big Arsenal fan, but now I don’t really care about them that much. I prefer to support my clients rather than a team.

“As a kid you see it as a big fantasy, being a footballer, but it’s just like any other job, it’s just a well-paid one. Once I get to know them, they’re exactly the same as any normal person.

“You’re not putting any of the money stuff in, are you?” No, I say.

The business of re-selling and rare clothing is nothing new. Back in the Nineties riots would erupt in malls across America over the latest Jordan releases, while in the late Eighties and early Nineties Ralph Lauren’s limited-edition Snow Beach and Stadium collections were so coveted that an infamous 1992 red, white and blue puffer was nicknamed the “Suicide” jacket. In a 2012 interview with Complex, hip-hop producer and obsessive Polo collector, Just Blaze said. “We called that the 'suicide' ski jacket because if you wore that out in the street it was like suicide. You would probably get killed for it.”

With the introduction of scarcity used as a tactic by brands to drive interest in sneakers and streetwear, a new breed of DIY entrepreneur began to emerge. Patient, savvy, well-connected and relentless, re-sellers learned where and how to buy the latest limited releases and who was willing to pay a premium for them in the aftermarket.

“Everyone has flipped shoes at one point or another”, Simon “Woody” Wood, founder of the long-standing cult publication Sneaker Freaker, tells me. “Which means we’re all resellers to some degree. It might be an unpopular and heretical opinion within the community, but resellers are an essential part of a healthy sneaker retail ecosystem.”

In the early aughts, New York skate brand Supreme turned the murky art of scarcity and hype into its rebellious calling card, indifferently luring young hordes of box logo die-hards to its Lafayette store for irregular Thursday ‘drops’ of t-shirts and hoodies that would sell-out as soon as the doors were opened. In London, Palace Skateboards has refracted the model of bright, recognisable, semi-affordable clothing with a we’re-in-the-club association to great, and highly profitable, effect. The kids still queue on Thursdays.

Luxury brands have followed suit. In 2017 Louis Vuitton collaborated with Supreme, before making ex-Kanye West collaborator and founder of high-end streetwear label Off-White, Virgil Abloh, its Men’s Artistic Director a year later (sales are up). Balenciaga’s lo-fi social media output, obtuse marketing and scarce production is far more in line with an irreverent streetwear brand than it is a near-century-old Maison. Odysseys have been written about hunting down a pair of its hideously iconic Triple S trainers. Burberry sells logo sweatshirts now.

“The problem”, Woody adds, “is that reselling has become so ubiquitous and so, I hate to say it, corporate these days. We’ve gone from a few natural born hustler kids making a few bucks on the side to industrial scale reselling. I’m sure brands are doing their best to ‘moderate’ this aspect of the business, but there’s only so much they can do.

“Regardless, reselling is just one part of the sneaker game’s constant evolution.”

What's the difference between 'reselling' and being The Plug? “If I just buy it and put it on a website, that’s reselling.” Sam says, when I ask him. “But if you’re buying it on request, that’s personal shopping. Does that make sense?

“If I buy 20 pairs of Jordans and put them up on a site, that’s reselling, if I get 20 pairs for eight clients, it’s not the same. I’m shopping for them.”

Interestingly, Sam doesn’t really seem to care about the clothes the way kids his age jostling in the rain outside of Palace and Supreme on Thursdays do. There’s a professional detachment between him and the product. Which begs the unusual question: if a hand passes over a Balenciaga hoodie or an Off-White trainer 10,000 times, does it start to just look like cotton or leather, mesh and rubber? The photos on his Instagram feed appear strictly business: him with his clients, and the clothes he’s selling. The Amiri seems more and more like a work uniform.

“I didn’t buy things for myself until I had made a certain amount,” he says. “I’d wear general clothes, just Zara or whatever.”

“It’s quite psychological I think. I know I don’t need more clothes, but I buy more clothes, even though I don’t need them. If I post the same outfit on Instagram and then wear it two weeks later, it looks like I’m just wearing the same item all the time.”

He looks around at his bedroom, at the Supreme box logos, the £750 hoodies strewn across his bed, the plinths to either side that prop up a trainer collection worth thousands.

“I’d say it’s a waste of money, but I kind of need to wear that stuff now, it’s part of what my clients expect.”

In a video posted to his Instagram page on 27 January, Sam addresses the camera alongside Patrice Evra, the now-retired French left back, one of the Premier League’s best ever. They’ve just had dinner at Mayfair’s Novikov, with its open kitchen, pan-Asian menu and glitzy Russian clientele.

“Man, Sam, this guy is a genius,” says Evra, laughing. “I say, Sam, ‘I need the Eiffel Tower.’ He’ll get me the Eiffel tower in 24 hours!”

He’s my new man. He’s the man, don’t be jealous.”

“I’m not sure he quite realises the position he’s in, the contact list he has,” his father, Grant, says on the phone, before telling me about a time recently where Sam was offered tickets to Manchester United vs Arsenal, in Manchester. Worried about getting back to London after an evening game mid-week, Sam texted Paul Pogba on the off chance he could sleep over. Of course, came the instant reply.

He has a cold and a meeting at 2pm, plus orders to chase and package. He’s starting to fidget while the photographer takes his portrait the way a 17-year-old would. We make our way out into the hall, the small dog doing its rounds.

Earlier, in his bedroom/office, I’d asked him how he differed from his rivals, what set him apart?

He offers an anecdote.

"In Australia, about a year and a half ago, there was this exclusive Off-White jacket that came out. No other personal shopper in the world had this jacket, but I had a contact over there and he told me [about it].

"I paid seven people £50 each to queue up, on top of the retail price for the jacket. It was one per person, and there were only 20 or 25 in the store. I got seven of them. And I had already pre-sold them to five footballers and two other guys on Instagram."

He looked out the window again.

“The other personal shoppers were asking me: ‘where did you get them!?’

“They had no idea.”