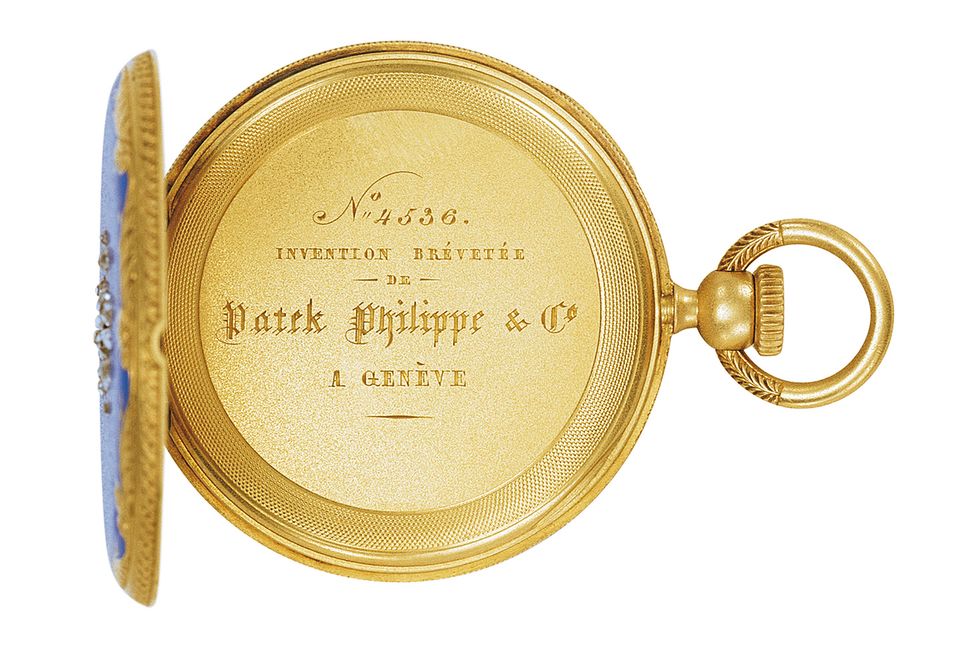

“When we were doing the show in London, a couple came in, a man in a wheelchair and she was pushing him,” recounts Dr Peter Friess, curator of the Patek Philippe Museum. “He said, ‘I have a watch here and it belonged to the husband of Queen Victoria’. I hear these stories very often, but I called the archive and got the numbers and it was true. How he acquired it, I don’t know. So, we have these pieces, even if they belonged to kings and queens… I don’t know exactly how we acquired Queen Victoria’s watch but I think it’s been in the collection a very long time, it was one of the first pieces we had.”

It was a fair question: how did Patek Philippe come to reacquire the watch that was presented to Queen Victoria in 1851 at the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park? The suggestion is later made that the watch that turned up in London might have been presented to some member of staff by the Prince Consort.

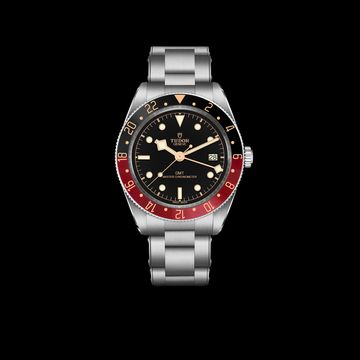

Queen Victoria’s decorated blue pendant watch is just one of several hundred pieces transported from the Patek Philippe Museum on Geneva’s Rue des Vieux-Grenadiers to the Watch Art Grand Exhibition 2019 at the Sands Theatre, in Singapore’s gargantuan Marina Bay development. Part mega-hotel, part luxury shopping mall, the complex is so vast it has its own canal network with Vegas rather than Venetian-style gondoliers shepherding a mix of tourists and well-heeled locals from Bally to Balenciaga.

But with one of the most comprehensive collections of watches and clocks anywhere in the world, spanning eight centuries and a multitude of makers, how do you decide which pieces to bring with you? There are certain pieces that would travel with the brand everywhere: the first-ever perpetual calendar wristwatch, Patek Philippe number 97975 from 1926 (the movement repurposed from an unsold 1898 pendant watch); a prototype Calibre 89 mega complication drum watch; an 1868 Patek Philippe, recognised as the first Swiss wristwatch (Breguet’s 1810 watch for the Queen of Naples, Maria Murat — Napoleon Bonaparte’s sister — was made in Paris).

After that mouthwatering core selection, Patek’s team in the region decided that automaton pieces would be of particular interest to the Singaporean audience.

“There are certain pieces that cannot travel because the climate would destroy them,” says Friess. “When you have certain pieces of wood or tortoiseshell or ivory, although there are other reasons you are not allowed to travel with those materials [such as endangered species regulations], so that’s over. We travel with a lot of enamel watches. Of course, we’re always frightened; when you take things out of the showcase a lot can happen, we are very careful but we have specially trained watchmakers here. Over the last five exhibitions, nothing really happened. We’re lucky. Or well prepared.”

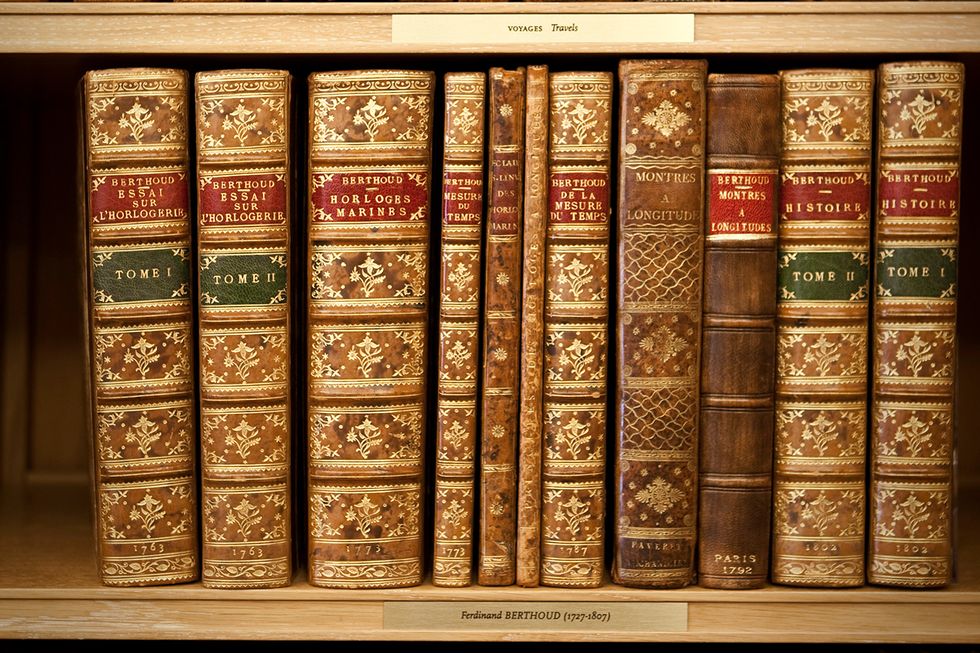

Patek Philippe’s museum is a unique proposition. It is funded by the brand and a working department of the business but it is not solely concerned with Patek watches and encompasses the history of watchmaking in general. The museum is the passion project of Patek’s honorary president, Philippe Stern, age 89, father of current CEO Thierry Stern.

Stern is still present in the museum “all the time” and according to Friess, who has been director/curator at the museum for seven years after stints at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, the Getty Museum in Malibu, and the Tech Museum for Innovation in San Jose, wants to “complete” the collection he first opened to the public in 2001. That kind of acquisition is Friess’s responsibility and an ongoing process. Just three weeks before I met him in Singapore, he had been in London, picking up two pieces from Sotheby’s.

But what would a completed collection look like? What pieces are still missing? Friess is careful not to give away too much information about what the museum has recently acquired or what it might be looking to purchase — that conversation is reserved for a close circle of trusted dealers, experts and auction houses — but he does reveal something of the strategy behind his efforts using a previous purchase.

“Patek Philippe created the first perpetual calendar wristwatch,” he repeats. “So, for the collection I wanted to have the first perpetual calendar in a portable watch. I told the story to everybody that’s collecting, ‘This is what I’m looking for, there must be one’. And one of the auction houses contacted me and said there will be one at auction. So I got it. It’s an English watchmaker Thomas Mudge who was also involved in [the] longitude prize — almost a winner — so we’re very happy with that. But there are other gaps and we’re still looking.”

Beyond cataloguing, conserving and exhibiting, the museum is a functioning department of Patek Philippe working with its watchmakers and product development teams to inform and inspire.

“When there is an interesting movement with something special like the first perpetual calendar from Mudge,” Friess says, “I call the engineers and they come by and they’re very eager to see the mechanism and study it. Sometimes they see things they have never seen before. That’s how history helps us to move on.”

We turn our talk to provenance, the element of the vintage market currently being exploited to maximum effect when auction houses deal in watches having previously belonged to the rich and famous. While Friess expects to know a watch’s origins as a bare minimum, he remains unmoved by association with celebrity.

“Personally for me, no. If the watch is very singular — when it was specially made for someone, with a nice painting or portrait of the person on it or something else — then we may be interested in it. But if it is a regular Patek Philippe that was just owned by somebody [famous] then not really, my heart does not really go up with that.

“But I have to be careful because people really love those stories. We have Duke Ellington’s Patek Philippe [a Ref 1563 split seconds chronograph] and when I see that, I always have his music in my ears. It adds a nice value to a certain degree. So if we don’t have that kind of piece in the collection we are interested, but if we already have that reference then we’re most likely not interested.”

As one might expect from the former curator of the Tech Museum of Innovation, Friess is more fascinated by technical achievement. His own highlight of the pieces shipped out to Singapore for the Grand Exhibition is something much more groundbreaking.

“It’s a watch in the first showcase called a drum watch. It only has one hand, to show hours,” he says. “It is one of the eight earliest pieces in existence; it was built before 1540. We’re very proud to have a piece like that. It’s not so exciting when you look at it and it can easily be overlooked but historically it’s one of the most important pieces. It’s a treasure.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.