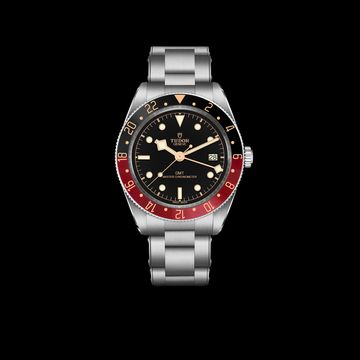

The watch industry has sunk its teeth into patina and it will take more than a stick inserted between the maxilla and mandible to prize the jaws apart. I am old enough to remember when it was almost axiomatic that vintage watches were restored; if you had a bubble back or a stripy Rolex Prince with a refinished dial and case polished to a showroom shine you were king of the world. But that was a long time ago.

These days, hyper-realistic close-up hi-def photography caresses every efflorescence of tarnish, lingers on every discoloured dial and celebrates in voyeuristic detail every scrap of decomposing luminous compound. Cases are triumphantly announced as “unpolished”.

Discoloured dials have long been described as “tropical”, and they have been joined by spider dials, volcano dials and names that embrace almost any type of degradation. It cannot be denied that if examined intelligently, marks and wear can be highly revealing: for instance, so-called “strap-rub” on the case back of a military-issue timepiece can be evidence of long-term wear on a Nato strap; if put in a drawer and forgotten, a timepiece from the days when luminescence came courtesy of radioactive materials will have “burn” marks on the dial, where hands have remained stopped.

But what started out as the philatelic preoccupation of a few Sherlock-minded collectors is now a mainstream obsession. The oxymoron is that what are, in essence, shortcomings in manufacture and materials are now celebrated for their “character”. Today’s primary market is increasingly influenced by the performance and popularity of vintage pieces: makers go into forensic detail to recreate the appearance of age without compromising ISO-mandated levels of performance.

A watch may look old… but works like new. The use of bronze became an industry-wide trend purely because of its instability, its ability to take patina, marking with every exposure to human skin or the elements; an eventuality that the industry has previously been dedicated to mitigating.

Watchmakers are thorough people and they are committed to exploring every recondite corner of the patina business, but sadly the industry was robbed of a major patina moment, when Steve McQueen’s Rolex was withdrawn from sale. His Lo-Temp Majesty the King of Cool is a posthumous marketing and sales powerhouse. Next year, it will be half a century since the appearance of the watch that was named Monaco but should be called the Le Mans after McQueen obligingly sported it during the eponymous movie. The film, like the race, is hard going and I would be disinclined to believe anyone who says he has stayed awake throughout. By far the best things to come out of it are the behind-the-scenes photographs showing McQueen with motorsport legend Derek Bell and, of course, the Monaco: the TAG Heuer everyone knows, but which would have passed into obscurity had it not received the benediction of HM the KoC.

Anyway, back to the “McQueen” Rolex: the story was that it was gifted by McQueen to a favourite stuntman, but was badly damaged in a house fire and subsequently restored by Rolex. The McQueen estate pushed back, however, and the watch was withdrawn from sale. It is a shame that the auction house was so responsible as it would have been an interesting test of the appetite for patina – it seems that prior to restoration the fire left the watch so “patinated” that it looked as though it had been baked and then deep-fried.

Had the watch sold well, I was rather looking forward to contemporary makers consigning brand new cases to pizza ovens and deep fat fryers to achieve the desirable “McQueen patina”.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.