When Tudor launched the Oyster Prince in 1952, the brand’s advertising emphasised the watch’s robustness in prosaic ways: it was shown being worn by a workman operating a pneumatic drill, and by a goggled motorcyclist speeding along a dirt track, with the legend “1,000 miles of merciless vibration”. Another advertisement referred to something more unusual: a band of British explorers out on the ice cap of northern Greenland, who had been supplied with 26 Oyster Prince wristwatches to use during their two-year expedition. The ad praised “the courageous men who wear these Tudor Oyster Princes [and] have unerring faith in their ability to withstand these tremendous hazards.”

The explorers, the advertisement told us, would be ensuring that “during the next two years, these wristwatches will undergo every ordeal a watch is heir to.”

The British North Greenland Expedition (BNGE) of 1952-’54 was a major event: its patron was Queen Elizabeth II, newly ascended to the throne and crowned while the expedition was in progress; it was also endorsed by Winston Churchill. It was mounted to investigate and record the terrain and geology of the North Greenland ice cap, with 30 men from the fields of science, the military and medicine working together to carry out seismological and gravitational research.

For Tudor enthusiasts the expedition has occupied an almost mythical part of the folklore of the brand ever since it took place. Besides its use in advertising, it was subsequently referred to in Tudor’s catalogues, while the watch that the explorers were testing to the limit would be fundamental in establishing the brand’s reputation for robustness and style. The question that always burned in the minds of collectors, inevitably, was: would any of the BNGE watches ever resurface?

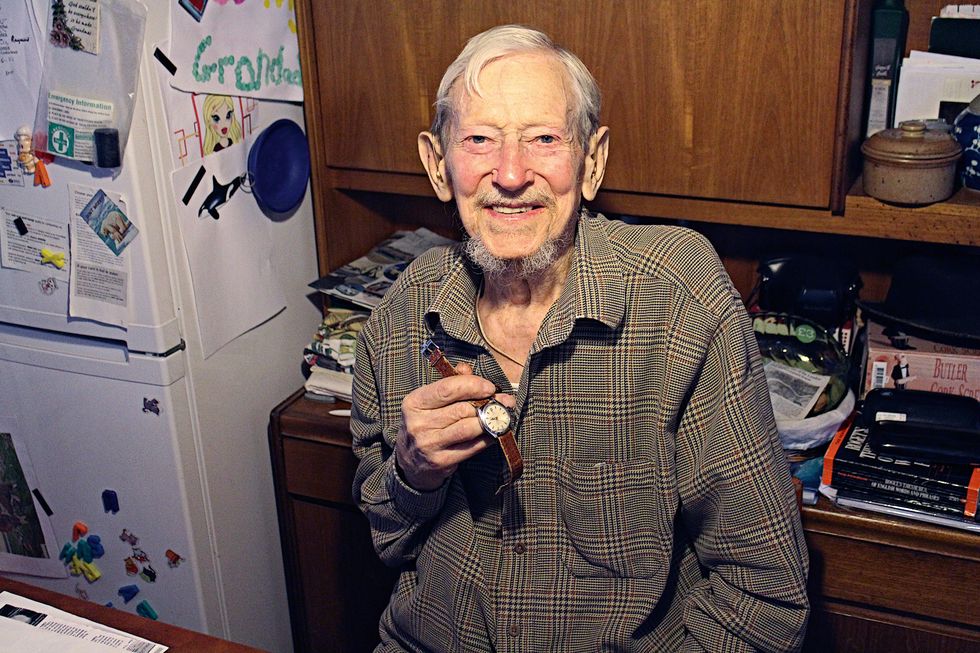

Finally, QP can reveal that one has – and with extraordinary timing; it being exactly 60 years since the expedition returned, and moreover, the moment that Tudor is launching back into the UK market after over a decade away. This is, however, entirely coincidental, for it was only in the spring of this year that the discovery was made. Just as remarkably perhaps, the watch has remained in the possession of its original wearer, Major Desmond “Roy” Homard, now 93 and among the last surviving members of the expedition, and it was rediscovered in the most humdrum of circumstances. Of all places, Major Homard found it in the back of a kitchen drawer. He made contact with Tudor, little realising just how significant a find this was.

For collectors, enthusiasts and most certainly for the brand itself, however, the discovery of an original BNGE watch was a tremendous moment.

It was the overwhelming urge of Cortland Simpson, a Commander in the Royal Navy, to mount an expedition to explore Dronning Louise Land, a relatively uncharted region he had only seen in the far distance from an air reconnaissance trip in 1950, that lay at the heart of the British North Greenland Expedition. He was fortunate to find a good appetite among senior officials of the services, as well as in the scientific community, to mount a scientific survey, and over the course of the next two years he slowly assembled the necessary support as well as an expedition team. The initial scientific complement was made up from glaciologists, geologists, a seismologist, a meteorologist, and a geophysicist, as well as a chemist and a doctor.

Many things were to be studied over two years amid blizzards, plunging temperatures and impossible terrain. Radio propagation analysis in conjunction with the Admiralty was a spin-off benefit, but at the heart of the scientific agenda were enquiries into specifics of the region, such as the rate at which the ice-sheet grows in winter and retreats in summer. One of the principal scientific goals was to make a gravity survey of the region. A two-year series of more than 300 gravity observations from the east coast to Thule, coupled with knowledge of ice thickness from seismological work, would provide knowledge of the state of balance of the ice-sheet and the underlying rock.

Roy Homard arrived a year into the expedition, replacing a team member who had returned home. Homard had joined the army in 1939, becoming an engineer with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. He saw postings in Italy, Austria, Hong Kong, Korea and Germany, throughout which he developed an expertise in working with mechanical vehicles, including tanks and tracked vehicles.

By 1952 he was Workshop Executive Officer (at the rank of Staff Sergeant) overseeing a facility maintaining military vehicles in Hanover, Germany. It was here that Homard saw a notice advertising for a volunteer with tracked vehicle experience for a scientific expedition in Greenland.

“I didn’t know what I was going to be up to, but I knew it would be very cold, very hard going and very dangerous,” he says now. “But I just said to myself, ‘I can do it’. I knew I’d be there for a year and a half or so.” Within days he was on his way back to the UK to make his journey to Greenland.

Homard’s job was the maintenance of Studebaker Weasels, tracked vehicles used by the expedition to navigate the ice cap. Not only did the terrain prove vastly challenging to the Weasels (and Roy had the principal responsibility for repairing them and coaxing them back to work after mechanical failures), but the whole team of scientists struggled against the terrain to extract data in much of the survey area. Moving around the ice cap for weeks at a time, living in tents and snow tunnels at temperatures as low as -50°f, battling blizzards, ice and crevasses, the teams (and their watches) endured exceptional hardships.

“It was very tough, and it got tougher,” says Homard. “I had to change engines out there. The vehicle work was really dreadful, because you’d have to take your gloves off to fix them, in this extreme cold. Travelling around was hard enough because of crevasses, but I was having to change tracks, bogie wheels, drive wheels, springs, engines and gearboxes. Doing this outside all the time was an awful business.”

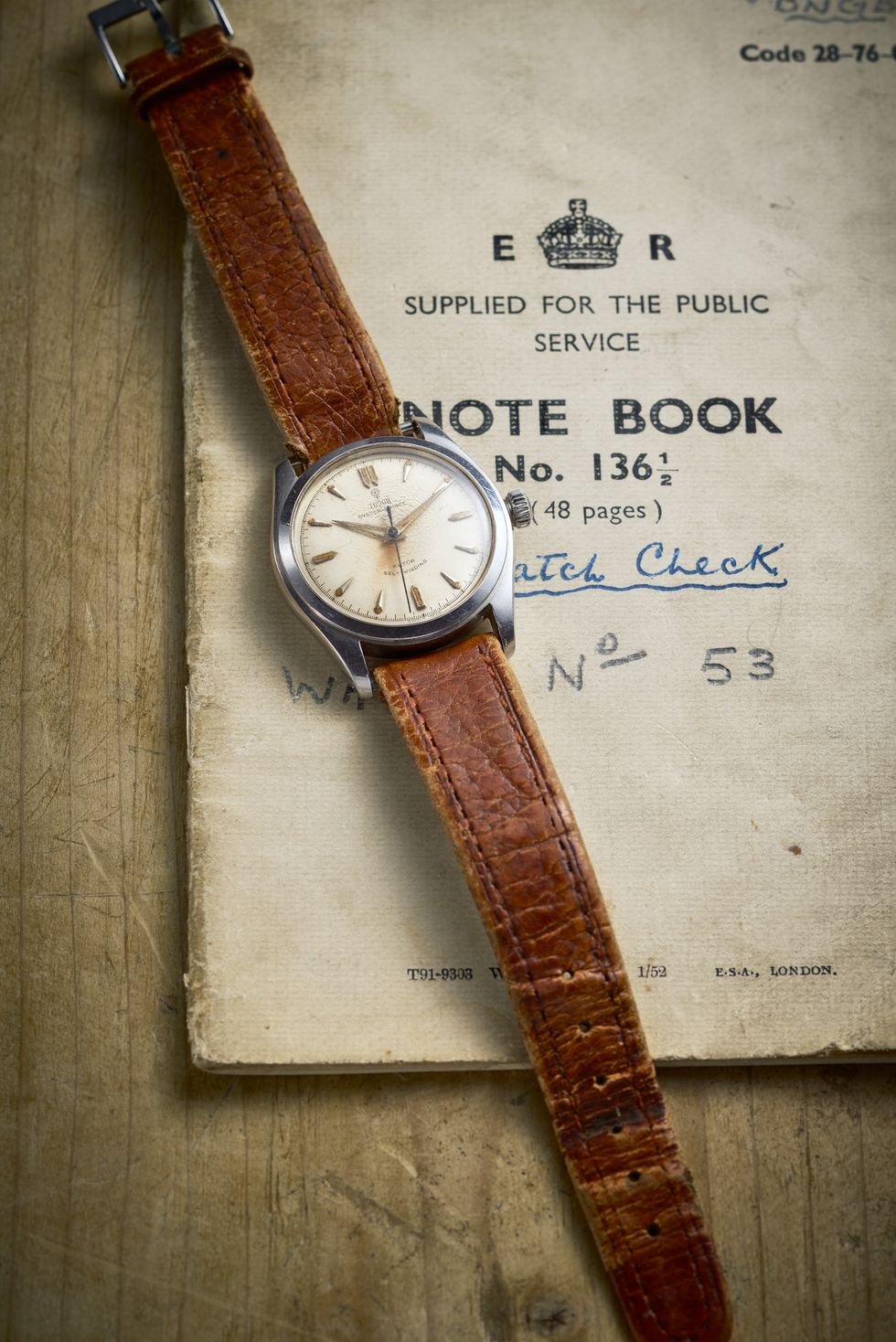

In August 1953 Homard wrote in a letter to his wife that he’d been given a Tudor watch “to keep a check on for performance during the year”. The Oyster Prince made use of the waterproof Oyster case that had been introduced by Tudor’s sibling brand Rolex in 1926, and carried an automatic movement – a modified Fabrique d’Ebauches de Fleurier (FEF) caliber 390 – at a time when most wristwatches were still handwound.

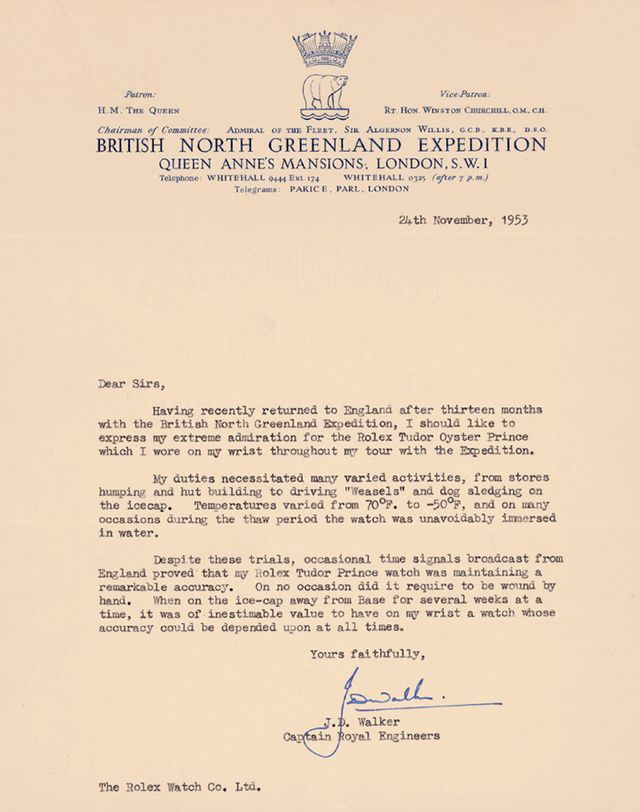

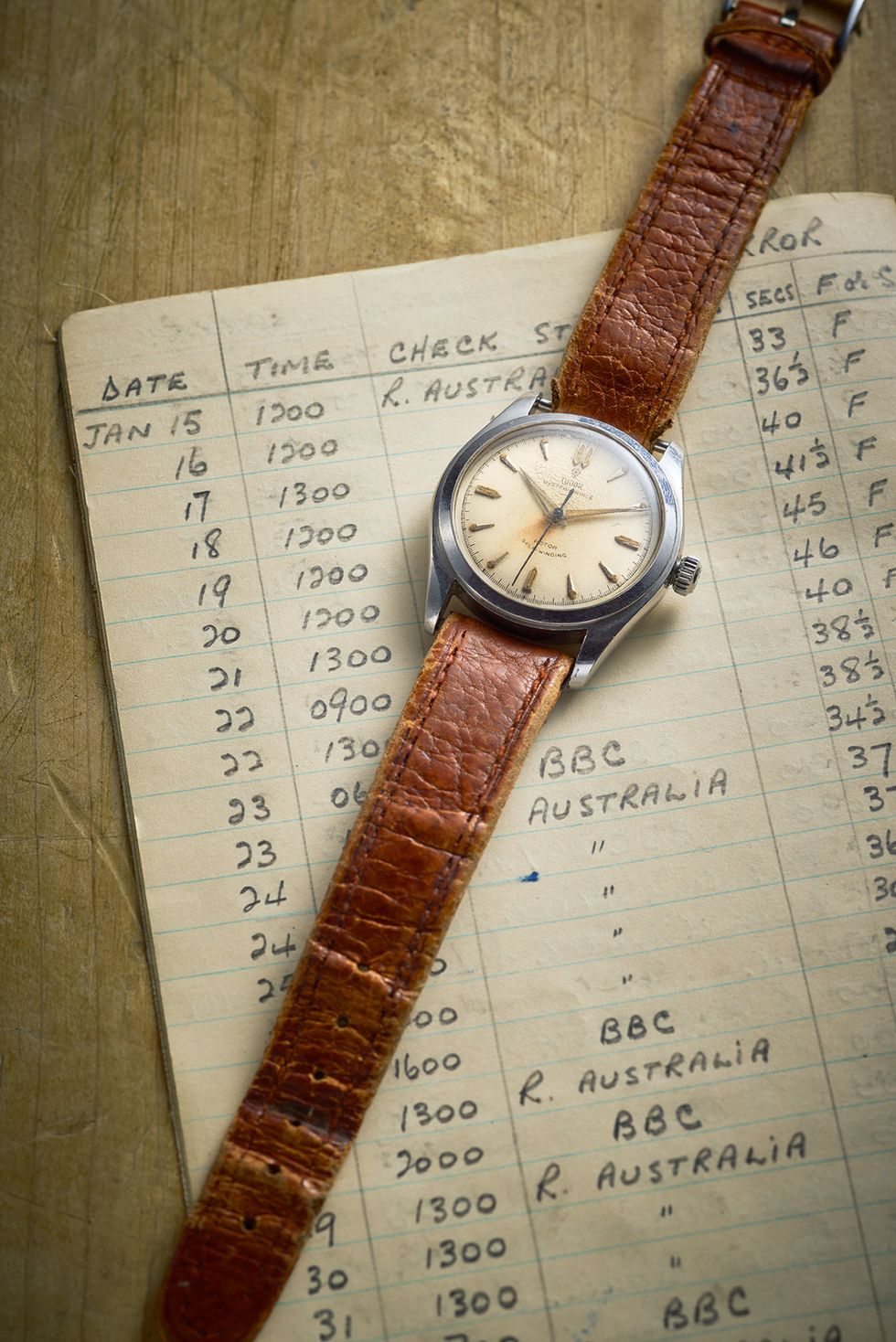

For Tudor, the expedition was an opportunity to test its brand new product in extremis. Thus the expedition was required to keep logs, recording the watches’ accuracy against radio signals broadcast by the BBC.

Following the expedition the logbooks were handed to Tudor. The log for the watch kept by Roy Homard, verifiable against its serial number, remains in Tudor’s archive and confirms his watch as having been present on the expedition.

Beyond simple timekeeping and testing on Tudor’s behalf, the watches were of crucial importance in the harsh environment of the Greenland ice cap – this is attested by the fact that Homard’s watch still bears the extended strap designed for wearing over arctic overalls.

In the first place, the watches formed part of a traditional navigational toolkit. So far north, magnetic compasses were less effective and prone to external influences, such as the metal cabins of the Weasels themselves. The survey teams had to resort to traditional sun-compasses: a type of sun-dial, with a central pin casting a shadow on an outer dial, marked off in 20 minute sectors, corresponding to five degrees of apparent motion of the sun round the earth. The process was described in Cortland Simpson’s book recounting the expedition, North Ice: mounted on the bow of the Weasel, the driver “looked at his watch and […] pivoted the face of the sun-compass until the shadow told the same time as his watch. Thereafter he drove with one eye on the watch and the other on the shadow, steering so that the two always told the same time.”

The watches also witnessed the monotony of long days and repetitive tasks. Homard’s diary records his day filled with maintenance tasks, the regular cooking duties which rotated (“the boys ate very little. I tried to make it light and fancy to tickle the pallet [sic]. Salmon, mashed potato, young tinned carrots…”), even his daily weight, and often the time for turning in at night.

Thus an expedition watch was no decorative item of jewellery – it was a vital piece of equipment, and Homard’s Tudor bears the typical scars and scratches of a serious campaign. That it should survive, only to be rediscovered recently, is all the more remarkable since Homard’s diary records that in February 1954 a signal was received from home that all watches “exported under customs bonds are to be collected in ... and declared on arrival in UK pending disposal”. The order to return the watches may well explain why other BNGE watches have not surfaced over the decades. One other Tudor Oyster Prince, belonging to the expedition’s medic, Doctor Jock P. Masterton, did come to light some years ago, but is now thought to have been awarded to Masterton after the expedition.

The watch had a rather quieter life afterwards. In 1956 Homard put his experience in Greenland to use as a member of the Trans-Antarctic Expedition led by Dr Vivian Fuchs, becoming in the process only the second serving British soldier (after Captain Lawrence Oates) to reach the South Pole. But for this mission he was issued a watch by the British company Smiths, the Tudor staying behind.

“My wife wore it while I was away on the Antarctic expedition,” Homard explains today, “and then it vanished. She wrote me a letter saying she’d been using it. But after I came home I didn’t think about it at all.

“Then, one day not that long ago, I noticed the box was still in my writing bureau, but the watch wasn’t in it. So I searched everywhere and looked in all my drawers, but I couldn’t find it and couldn’t imagine what had happened to it.”

Homard’s wife sadly died some years ago, and though he remembered a passing conversation they’d had about the watch a few months prior to her death, no light had been shed.

“We changed the subject and she didn’t mention it again, and I don’t know why she brought it up. I thought she must have given it away, or even sold it,” he says. “But it bothered me and I really looked for it. I went through every drawer in the house, and there it was in the back of a kitchen drawer of all places, hidden among things that must have been there for years. But I don’t really know what had happened to it for all that time.”

As the only confirmed watch remaining from one of the most renowned adventures in watch lore, Homard’s Tudor Oyster Prince becomes a true historic artefact. Homard has therefore decided to donate it back to Tudor, where it will take pride of place in the brand’s extensive archive of important vintage pieces – an archive that has proved so much inspiration for its contemporary designs. A momentous occasion – and all for a watch that spent so many years in a drawer.

This article originally appeared in QP Magazine in 2014; the watch belonging to Roy Homard was exhibited at SalonQP in November 2014 and subsequently donated to Tudor's archives. In return, a specially engraved Tudor Heritage Ranger (seen as the direct descendent of the Oyster Prince) was given to Major Homard at SalonQP.

Sadly, Roy Homard passed away in 2015. We dedicate this article to his memory; you may be interested to read his obituary here.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.