“I’m not a hero, I’m just a pastor,” Kim Seongeun tells me in a London office. After watching Beyond Utopia, a documentary about North Korean defectors, you may find those words hard to believe. The unassuming figure, also known as Pastor Kim, has helped around 1,000 people escape from the totalitarian state for over 20 years, as they embark on what is one of the most dangerous journeys in the world: across the Yalu River, into China’s mountains, and along inhospitable borders, to reach the haven of South Korea. The pastor’s “just” begins to look a little misplaced.

The documentary, directed by Madeleine Gavin and in cinemas now, follows two escape attempts from North Korea: the Roh family, travelling with two children and a grandmother, and the son of Soyeon Lee, a defector based in South Korea, who hopes to reunite with his mother. Gavin intersperses those gripping real-time stories with a history lesson about the two Koreas as well as footage, covertly shot, from inside the dictatorship. Whatever you think of the tyrannical regime, as much as we read about weapons of mass destruction and Kim Jong-un’s leadership, your ideas will likely be changed by this picture, of a backwards country with food and water shortages. One where civilians must gather human excrement for fertiliser. At the centre of it all is South Korea-based Pastor Kim, who has built a network of “brokers” along the escape route in China, Vietnam, Laos, Manchuria and Thailand.

Challenges include the Chinese authorities (who will return any caught defectors to North Korea), treacherous jungle crossings, the weather. Covid made things even harder. And there is little money to work with when things go wrong. The church is one of the only establishments funding the missions, the pastor explains, and the South Korean government can do little for diplomatic reasons. As you might expect, the pastor – the kind of reassuring person you would text in a crisis – has a lot of tales. One of the strangest rescue missions happened in 2013. He was supposed to help one orphan escape but along the way, 14 villages joined the mission. Pastor Kim prayed, and suddenly, he received a phone call from a Korean emigrant in American who had read online about The Caleb Mission, the organisation which Pastor Kim runs. She transferred $12,000 immediately to help. He attributes that to God’s blessing, but any mission would not have been possible without the pastor’s groundwork.

A little like Oskar Schindler, Pastor Kim has led a life that could inspire Hollywood films. He helped his now-wife to escape North Korea. Then he helped her friends. He has broken bones and undergone surgery from injuries sustained on escape attempts. While on a mission, his son died. “I promised to my son and to God that both my wife and I would devote our life to rescue North Korean defectors,” he says. “That’s what keeps us going.” But still: what does he do when he has a bad day? This is the first time, his interpreter tells me with some surprise, that he has been asked this question. Sometimes, the pastor explains, he wants to go on vacation with his daughter and wife, but it is hard to find the time. “Without God, I probably could have become an alcoholic or drug addict, because I have to deal with a crazy amount of stress and trauma and death.”

Beyond Utopia plays out like a thriller. When you watch extraordinary mobile phone footage of escapes – none of which is a recreation, the introductory credits stress – the word that often comes to mind is: how? How did the filmmakers convince defectors, who surely have other things on their mind, to be on film? Gavin assures me that all defectors gave consent for the footage to be used and Pastor Kim’s network has cameras hidden along the over 800-mile border of North Korea and China. Early buzz for Beyond Utopia, which debuted at Sundance Festival and won in the audience category for U.S Documentary, means many more people will soon be watching (especially if the Oscars come calling).

In 2014, The Interview, starring James Franco and Seth Rogen, caused an international crisis from Hollywood. The comedy, which mocked North Korea and depicted the death of Kim (with plenty of R-rated jokes), led to a hack of its owner Sony Pictures. Embarrassing emails and films were leaked; hackers threatened to attack film premieres. The US has claimed the hacks were organised by North Korea, though its government has denied involvement. Does Gavin think Beyond Utopia might have a similar blowback? Authorities definitely know about the film, according to the director, as well as the work of Pastor Kim. “In The Interview, they mocked Kim Jong Un and blew a rocket up his butt – that is something that was intolerable to him,” Gavin says. “What we say about Kim Jong Un in our film, is that he’s a strong man, and a brutal dictator, and by all accounts, this is not something that particularly bothers him.”

One of the bittersweet feelings explored in Beyond Utopia, and one which you may wish to see explored more fully, is the torment defectors experience once they arrive in South Korea. “If you go on a fancy vacation, you still miss your hometown and your food,” Pastor Kim explains. “So obviously for North Korean defectors, they miss their home, they miss their food.”

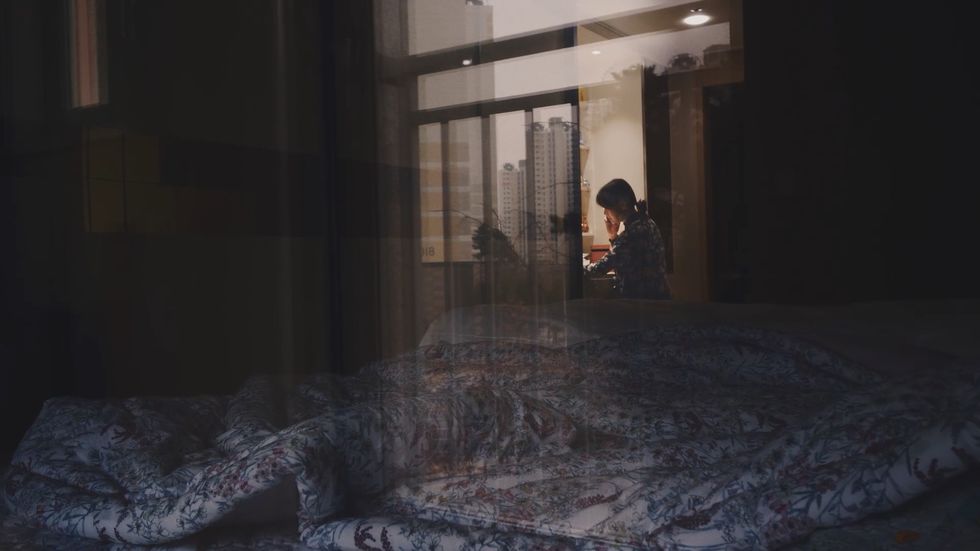

During the pandemic, he set up a community centre in South Korea for defectors, where they meet to cook together and share information about what’s going on in their hometowns. “They all have the same experience and heartbroken stories.” On rare days off, he visits the centres and catches up with the defectors. Or else, they come to church on Sundays; they learn to lead normal lives, they listen to K Pop. The children love BTS. Life, it seems, often comes down to routine, food and pop music.

‘Beyond Utopia’ is out now in cinemas

Henry Wong is a senior culture writer at Esquire, working across digital and print. He covers film, television, books, and art for the magazine, and also writes profiles.