By his own account, Matt Smith is terrible at making decisions. The 39-year-old actor dithers before giving a yes or a no and — “Even worse, so much worse,” Smith says — he continues dithering long after his commitments are in place. Back in 2010, when he landed the career-shaping lead role in Doctor Who, one of Smith’s first actions was to second-guess his own casting. (He asked his agent, should I really do this? And his agent said, oh absolutely, you’re doing this.) Smith’s friend and fellow actor Claire Foy tells a story about meeting him at a reading for The Crown, that rich, part-historical Netflix drama about the British Royal Family that began in 2016, bringing them both great acclaim, but about which Smith was hesitant. “I’m not sure I wanna do this,” Foy recalls him muttering. “I’m not sure I wanna do this.”

Soon, Smith will appear as a Westerosi prince in HBO’s House of the Dragon, a costly and ambitious expansion of the Game of Thrones franchise that is sure to be closely scrutinised by fantasy obsessives, entertainment-industry executives and cynical TV critics when it arrives on our screens this month. You can bet there was no quick, snap decision from Smith about this job. No iron certainty about whether to accept. “Look,” he says, pushing his longish, dark hair off his forehead. It is a changeable July day and Smith, who is 5ft 11in, wears a navy pullover, black jeans, black Reebok classics and grey-rimmed prescription shades that he swaps for thinner spectacles whenever the sun moves behind a cloud. “Look, none of this is helped by the fact that, as an actor, you’re constantly self-referencing your own feelings. Feelings, feelings, feelings! When sometimes it’s not about feeling. It’s about deciding and doing. Somehow, though, I always seem to find myself dithering things out.”

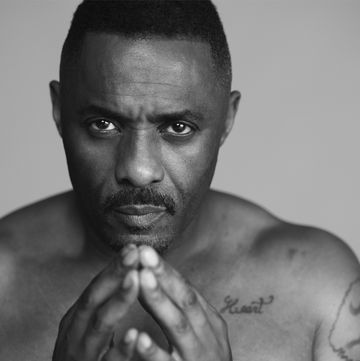

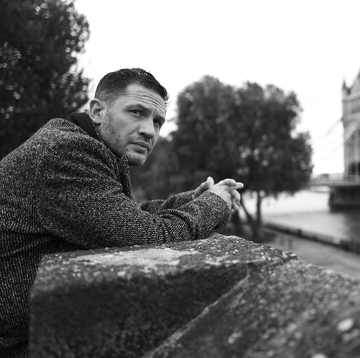

Odd that he should have this tendency, away from his work, because whenever Smith is performing he transmits only conviction, whether as an impetuous Doctor, a simmering Prince Philip in The Crown, or a gnarly Patrick Bateman in the musical of American Psycho, a role he originated for the London stage in 2016. When you think of the best British actors in mid-career, the likes of Andrew Garfield, Riz Ahmed and Ben Whishaw are huddled in one group, experts at teasing out sympathy for characters by rendering them as troubled or tortured introverts. Smith is in another group. He is swinging off the fixtures with Daniel Kaluuya, Benedict Cumberbatch and Toms Hardy and Hiddleston, who bring audiences along by the sheer force of their confidence. There was little footage of House of the Dragon available at the time of writing this; Smith is tight-lipped about his contribution. But expect phlegm. Expect nerve. Expect a performance dialled up rather than down from an actor who knows exactly what he’s doing when the cameras roll…

Yet here he is, in person, about to undergo a textbook Smithian wobble. We’ve agreed to meet close to where he lives in north London, to go for a rambling walk over Hampstead Heath. He arrives whistling, chest thrust out, by all visible indications a decisive man — and after scanning the scene, he suggests we have a drink in a pub instead. Diet Cokes poured and paid for, a table secured, he scans the scene again — and suggests we do that walk. So we set off. It’s a two-hour wander. Before we’re done, Smith will have introduced and explored many subjects, light and large, proving himself more than capable of firm opinion and solid emotional counsel. But one of the first things that happens is that we pass a lovely old house he almost bought. The sight of it brings an actual moan of dismay from Smith.

“A long, drawn-out process, that. And one of those indecisions I came to rue.” About as soon as it was too late to do anything proactive about this dream house, he says, and after it had been bought by somebody else, he came back just to stand outside and stare at it: “To live in an element of regret.” I notice when he says this that he has a streak of grey in his hair. And no wonder. “Oh, I’m a fucking nightmare to live with, let me tell you… I’m lucky, though. I’ve got friends and family who’ll try to pull my head out of my arse as much as possible.”

He is close with Noel Gallagher, Britain’s unofficial president of plain speaking. The pair recently spent Glastonbury weekend together. By admiring and emulating his friend Claire Foy, Smith has been trying to approach his career choices with more smartness and clarity, too. As for the most important figure in his life, his father, a Northerner born and raised in Blackburn — he always had a useful stock of no-nonsense phrases to undercut Smith’s vacillations. As we walk, Smith does a booming impression: “Bloody hell-fire! Just make a decision and ge’ron with it!” Now that he’s approaching 40, Smith says, he intends to add some Foy-like clarity to his character. Gallagher-calibre bluntness. Blackburnian steel.

He asks if I have any children, and says: “I would imagine having children allows this all to fade away a bit. Because there just isn’t the time to wank on and on. There isn’t the time to be so self-involved, not if someone needs to go to school or they’ve got spaghetti hoops up their nose.” Smith doesn’t have children himself. For a period of his thirties he lived with the British actor Lily James, but that relationship ended around 2020. If he’s involved with somebody now — anybody other than his Irish terrier, Bobby — Smith isn’t saying. “But I do think that’s what life is all about in the end. Children. Making a family. You know, when you’re dead, and you’re on the slab, that’s what’ll count.”

Our walk has taken us on to an open, sun-baked part of the Heath, where the grass comes up to our knees. There’s nobody around, only crickets, and Smith risks quoting poetry. There is a part of TS Eliot’s poem ‘The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock’ that is about death-bed rumination. He has the whole thing by heart and mentally he scrolls to the relevant lines. “When I am formulated, sprawling on a pin/When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall.”

He was born in Northampton in 1982, second child of David, who ran a plastics company, and Lynne, who worked in promotions and then for a newspaper. His older sister Laura, later to become a professional dancer, appeared in local musicals. Smith himself was a promising footballer. He played all the time, 10 hours a day, travelling to junior training sessions at Nottingham Forest and later joining Leicester City’s youth team. Football was his identity, and useful playground armour for a kid who had a mild speech impediment. As a teenager he was diagnosed with spondylosis, a serious back complaint, and he had to take a year off sport. It left him in a race to get fit again in time for an important round of selections at Leicester. Smith was 16 or so. He didn’t make the cut.

Now that he is an adult, his accent drifts freely between two distinct registers, the Lad and the Gent, trackable to those tribes that shaped him as a young man: footballers, then actors. An influential drama teacher persuaded Smith into school plays, and from there on to an apprenticeship course at the National Youth Theatre in London. He was studying drama and writing at the University of East Anglia when he was cast in his first professional play, That Face, at the Royal Court. The actorly Gent emerged to contend with the footballing Lad, and for the rest of Smith’s life his conversational voice has winged between. “My friends from home say, ‘Urgh, he’s using his actor’s voice again.’ I don’t even notice I’m doing it.”

After That Face, Smith was part of a touring production of The History Boys. He appeared in an adaptation of a Philip Pullman novel for TV. In 2008, when David Tennant announced he was leaving Doctor Who after a long, successful run, Smith was asked to audition. He had never seen an episode. He admitted as much at his read, cheekily blaming the BBC for airing the programme at 7pm on a Saturday night: “At which time, I’m in a pub.” Despite — or maybe because of — a lack of familiarity with the material, Smith had the nerve to freewheel, at one point improvising a conversation with a fish in a tank in the audition room. “I got the job in September,” he says. “But because David was still doing the part, I couldn’t tell anyone for months.” Actors who work together typically make polite enquiries about each other’s future. What are you doing next, love? For ages, Smith had to answer with a grunt: nada.

“I told my mum. My dad. My sister.” As for his two best friends, they knew what he’d auditioned for. He was sat in a north-London flatshare with one of them when an advert for Doctor Who came on TV. Something about Smith’s manner, some twitch or smirk, set his mate thrashing about, pointing: “You got that part! You got that part!” After a secretive Christmas Eve photoshoot, he told his grandfather the following morning. Everyone else in his life found out when the news went public in 2009. “And everyone was like, what the fuck, man?” Smith was 26. Suddenly it was as though he were a royal consort, insta-fame, but not for any tangible achievement — more for what he was preparing to do. There was serious post-Tennant pressure on Smith as filming began. A few weeks into shooting, he called his father David in a panic. He wasn’t sure he could carry on. David told him that he could. “The hardest thing in life is to adapt. But you’ve got to adapt.” Smith quoted this advice when he appeared on Desert Island Discs in 2018, describing David as the greatest influence on his life, “bar none”.

Smith’s Doctor debuted in spring 2010. It was clear within minutes that it would work. He was watchable. Original. With his unusual energy, he seemed to embody narrative momentum, dragging viewers along by the earlobe. He was on Doctor Who for four years and he learnt lots, he says, mostly about work ethic. This was an actor’s gym. “The line-learning was insatiable… and I suppose it sharpened a tool for keeping secrets, too.”

Useful, given his current job. There has been omerta around House of the Dragon since HBO announced it last year. Smith points out that there is a source book by George RR Martin, “which takes some of the pressure off”, in terms of him accidentally blabbing. We know from that book that House of the Dragon is a prequel to Game of Thrones, set 200 years prior and recounting a bloody dynastic squabble over Westeros’s Iron Throne. Where Game of Thrones was about rival families — immaculate, blond Targaryens, beardy Starks, those shifty rich kids the Lannisters — the new drama is all Targaryen. Smith plays one of the contending blonds, a prince called Daemon who, in Martin’s source novels (mild, mild spoiler), is a longstanding contender for power.

It is not clear how many seasons of House of the Dragon Smith has signed up for; or how many years of his forties are to be spent under a glued-on yellow wig, but my guess would be several, five at least. Having already done an exhausting stint inside one fan-policed fantasy world in his twenties, why do another? He speaks of the quality of the scripts, of HBO’s track record in prestige TV, of the honour of being asked. Will it make you happy, I ask? “Well,” he says, “watch this space. I don’t know.”

To date, his best work has been in contained projects, time-limited by agreement. He was well-reviewed in Unreachable, a play that ran for four weeks at the Royal Court in 2016. The Crown debuted that year, Smith’s involvement ending after two seasons, in 2018. On paper, the role had looked unpromising, a hospital pass. Smith as the young Prince Philip? He wasn’t posh. He’d grown up around anti-monarchists all his life. Yet Smith and Peter Morgan, The Crown’s creator, found something melancholy, compelling and necessary in Philip. Smith was nominated for several awards.

“Didn’t win a thing,” he chuckles. Did he mind that? Smith pushes out his lips. “I don’t have a lot of time for jealousy.” Everyone else on those early seasons of The Crown seemed to win, though. Foy picked up a Golden Globe, an Emmy. I ask Smith whether the footballer inside him — that week-in, week-out competitor he used to be — cared about being bested. He tilts his head, considering, and says, “Don’t get me wrong. There’s always a moment, after ‘And the winner is’, that stings you. Because you’re there, you’re in a fucking suit, you’ve got your mum with you, you’ve flown to Los Angeles. And because everyone around you who’s in the same show keeps winning! But it stings for a nanosecond. It isn’t important.” He continues, “Claire won everything. My award was the absolutely beautiful and gracious things she said about me in her speeches.”

The two became firm friends, not only from their months on set together, but from their time travelling to promote the show for Netflix. Often laugh-out-loud funny as a pair, they publicly mocked each other’s unwise film choices (Smith’s 2016’s horror-comedy Pride and Prejudice and Zombies was an obvious target) and they teased out a running joke about Foy’s disdain for science fiction. She could scarcely believe some of the scenarios Smith had agreed to take part in on Doctor Who; for instance, riding a flying shark to deliver Santa’s presents on Christmas Eve. You wonder what she’ll make of him with shoulder-length blond locks in a fantasy-scape full of CGI dragons. How would Smith talk Foy around to House of the Dragon if he had to? “To be in it with me? There would be no words. To watch it? She might anyway, out of common courtesy or only to point and laugh. But no. A very hard sell.”

Smith and Foy had not long finished a stage run at the Old Vic, appearing in a two-hander about climate change called Lungs, when the pandemic struck in 2020. That year, to raise funds for the venerable theatre, the pair performed Lungs one last time in front of 1,000 empty seats, a paying audience watching over Zoom. The stop-start months that followed were as bizarre and directionless for Smith as they were for any of us. “I had nothing to do,” he recalls. “So I got fit. I wrote a bad film script. And I learnt a load of poems off by heart… You feel a wanker, being an actor and flowering on about poetry. But I got a lot out of it”

Learning Eliot by rote, through 2020 and into 2021, he found that he was drawn to that doleful ‘Prufrock’ poem in particular. It seemed to start on a sigh. Smith’s life was about to get a lot tougher that year.

“When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,” he is reciting on the Heath, “Then how should I begin/To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?”

Our walk has taken us into a broad open field. Sun beats down. Eliot’s words put us in mind of mortality, and we begin to talk about our fathers. David Smith died in May 2021. My own father died recently as well. Smith has already shown himself to be a warm, curious companion, a keen asker as well as answerer of questions, effortlessly generous in spirit. But even so, he surprises me by turning around on the path, when he hears about my loss, and clamping me in a tight embrace: “Mate.”

We carry on through the field, pretty peeled, pretty raw, comparing notes on bereavement. It’s hot, and for a while the conversation falls into a hazy limbo where we’re not quite interviewer and interviewee, not quite confidential intimates, just sons, trying to make sense of an absence. Smith asks whether I found it hard returning to work, and I explain that profiling him is my first job since the funeral. His own first job was on House of the Dragon. He found going back on location extremely difficult, and he worries about future collisions between his professional and personal life if he’s asked to talk about David when he embarks on his promotional commitments for HBO. “Once you speak once, it becomes for people to discuss with you.” He really doesn’t want that.

So no quotes, here, about the loss of his father. No words of his that can be taken up, stripped of context, and set down again in a tabloid story. Neither of us, anyway, can come up with a better description of parental loss than the one that Smith heard from a friend. It goes like this. You’re walking down the street. It’s a random Tuesday. Then somebody swings a golf putter in your face and that’s it. Tuesdays won’t ever be the same. Nothing will.

We stop on a bench with a view over the treetops to London’s skyscrapers. Smith runs a hand through the greyer part of his hair. Greyness is in his genes; David went fully grey at 30. Smith considers himself lucky to have got to 39 with more colour than not. “I reckon I’ve got a couple of years. Then it will all go. I’m not gonna dye it. I’m just gonna let it happen.”

The thought of it puts him in mind of that coming watershed birthday in the autumn. He won’t have a party for his 40th, he says, having tried that a decade ago, when he realised he was a better attendee than host. Instead, he might mark the event with a bucket-list ambition: going to Munich for Oktoberfest. There, he’ll drink a few steins, let midnight strike, and settle into a new phase, not quite young, not quite old: a time when you’re “the middle child in your own life”, to use Smith’s off-the-cuff phrase.

And who knows, he might get something done about his chronic indecision, too. “I’d like to try to cut away the bullshit. Become more acute. My dad used to tell me, ‘There’s no such thing as a bad decision. The only bad decision is no decision.’ And that’s true, I think.” So no more dithering. Wham-bam decisions only. Zero regrets. We’ve walked off the Heath by the time he says all this, and it’s unfortunate timing, because now that lovely house comes back into view.

Smith gulps. Ah well, one dither for the road. “Excuse me,” he says, “I’m just gonna have a last little moment of regret while we pass the front door.”

Buy the new issue of Esquire here, and subscribe here

Written by Tom Lamont, photographs by Boo George, styling by Catherine Hayward