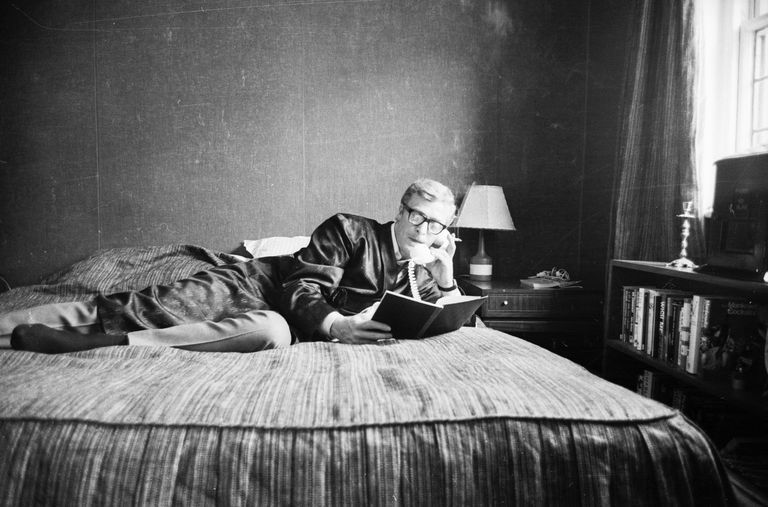

A friend of mine met "the love of his life" the week before London went into lockdown. They were at a mutual friend's birthday and had one of those evenings where you don't leave the other person's side; talking on the sofa for hours, time disappearing, neither body moving no matter how many chances they have to stand up and step away.

When, a few days later, the government made their nascent relationship all but illegal, they agreed to put things on pause. The prospect of speaking but not being able to see or touch each other was too agonising a reminder of the hours they should have been idling away together in beer gardens.

There is something perfectly tragic about meeting The One right before you enter a world where you're forbidden from seeing them. It's almost Shakespearean – a 21st century Romeo and Juliet, separated not by familial antipathy but instead a virus that, like the poison those star-crossed lovers share, could be passed along with a kiss.

Those who have tried to keep the flame alive during lockdown – or chosen to spend the seemingly endless waves of time looking for new love – have been abetted by the dating app industry which, as the pandemic spread, went into overdrive to launch features which allowed users to get closer while staying apart.

These included badges which alert other users that you're up for virtual dating, video calls or voice notes features, and suggestions of how to stage successful virtual dates with other users. In March, Bumble launched a partnership with Uber Eats so that users could eat the same takeaway together at the same time, and Tinder has been testing a video feature which gives users an in-app trivia game to play against each other, like speed dating conversation cues for the digital age.

Taking the prospect of meeting in real life off the table, and confining interaction to separate screens, might sound at odds with the exhilaration of dating and chance encounters, but some have found a new kind of intimacy can come from lengthened conversations and having to spend time really getting to know someone.

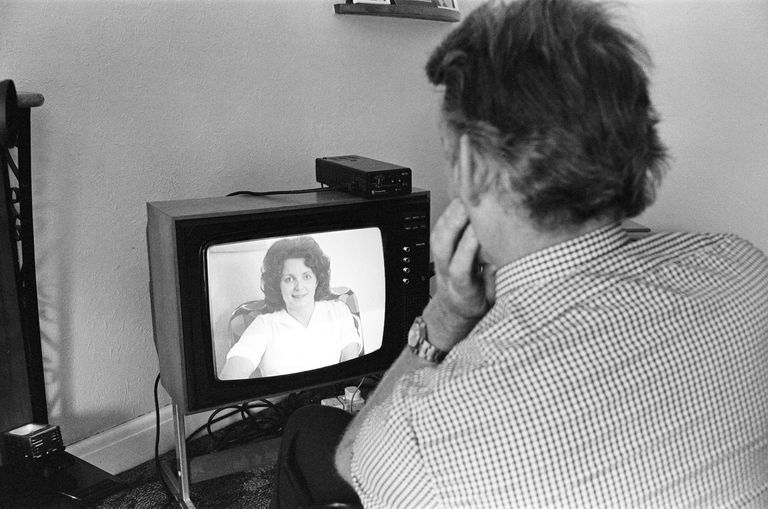

James is a 30-year-old living in Manchester who has been using Bumble to virtual date during lockdown. On his first video date with a girl he had been speaking to on the app, they both pressed go on an order of dumplings and a Katsu curry at the same time to feel like they were sharing the same food. "At the start it was a little awkward being on video," he said. "But after about ten minutes we felt like we were in the restaurant together."

Since that first meal they have left their virtual restaurant and gone for a drink together in two virtual pubs they each designed, as well as making playlists of the ten songs they would pick to listen to for the rest of lockdown. "The physical interaction is missing but it gives you an opportunity to get to know someone better," he says. "I do think people will approach dating differently going forward."

Bumble introduced video and voice calls to the platform last year, but with statistics from mid-March showing 88 per cent of users had never been on a virtual date before, lockdowns and quarantines around the world have made the feature a necessity rather than an unorthodox stage of courting. James is one of many for whom Bumble has brokered a connection while stuck inside, with the app recording a 21 per cent increase in messages globally and a 56 per cent increase in video calls during the pandemic.

Naomi Walkland, associate director for EMEA marketing at Bumble, believes that virtual dating has created space for more meaningful conversations, as the courting period has become elongated. "I think there’s definitely going to be a move toward virtual dating becoming the norm," she tells me, an idea bolstered by a recent statistic that 29 per cent of Bumble users will continue to video date after lockdown lifts.

"A lot of our users are arranging video calls through the app as a 'pre-date date'," she adds. "And I can really imagine that will become a moment: you start with the video call and have your first date there and then move into your real life dates."

Hinge CEO and founder Justin McLeod is similarly buoyant about how virtual dating is inspiring people to connect during the pandemic. "We’ve seen about a 30 per cent increase in the amount of messages sent on the platform," he tells me on Zoom. "So clearly people are using this time to concentrate on their dating lives."

If that sounds a little too close to the screening stage of a job interview, well, that's kind of the point. McLeod believes that video dating will remain a part of the vetting process of dating for users in the longterm. "As a vibe check I think will make people’s dating lives so much more successful because you don't have to go through the frustrating experience of showing up on a date and instantly realising this person is not your type."

Though couples are physically apart, virtual dating features can offer a kind of slow-burning intimacy, which the tennis match of back-and-forth messages before a rushed weeknight date often cannot. One man I spoke to told me he finally had the time to get to know someone without the immediate pressure of setting a date to meet up with them, an exercise which often proved an avoidable waste of time. In another respect, several women spoke of how they felt the slightly awkward experience of video dating was worth going through for the sake of their safety before meeting a complete stranger in person.

Adding voice calling and voice notes means that you are able to hear the way someone really speaks rather than just reading their painstakingly edited messages. For a generation that relies on messaging platforms for communication and often avoids picking up the phone at any cost, hearing someone's voice can have a thrilling intimacy. Voice notes show us parts of people which texts cannot: the way someone inflects certain words, the way they speak when they've just woken up or the sound of their laugh.

One woman told me that a colleague had forwarded the voice notes that a match had sent her and that listening to them was almost unbearably personal, closer to reading someone else's diary than their text exchanges.

This might seem like a counterintuitive step away from what many see as the entire point of dating apps – helping people have sex – but many were walking that path long before lockdown made intimacy impossible. In a chapter about internet dating from her 2016 book Future Sex, the essayist Emily Witt discusses how dating apps have become increasingly sexless and morally immaculate. She writes of "the clean, well-lighted place", a phrase taken from the title of a Hemingway story which talks about creating a "women friendly environment for sexuality", which dating apps need to achieve in order to draw women – and therefore men – inside.

"My avoidance of any overt reference to sex meant that internet dating was like standing in a room full of people recommending restaurants to one another without describing the food," Witt writes. "No, it was worse than that. It was a room full of hungry people who instead discussed the weather."

Of course, dating platforms are also hosting video stripteases, horny midnight text exchanges and phone sex too. But the apps are keen to show the experience as being about 'meaningful connections' – tech-speak for an interaction with relationship potential – which are measured by robotic metrics like minutes spent on a call or the number of messages exchanged.

This idea of talking about the weather when hungry becomes even more extreme during a lockdown when the prospect of sex is impossible, adding a sexual tension that is almost unbearable. I spoke to one woman about a virtual date she had that was going perfectly until they got so drunk they were unable to resist each other. This ended in her getting an Uber to his flat and waking up with a raging hangover and guilt at having broken lockdown rules. She never spoke to the man again.

Perhaps, had she stuck to virtual dating, she wouldn't have rushed into something she regretted. But it's equally likely she might have wasted four months on someone, only to find out they had no sexual chemistry in real life.

So is virtual dating a useful stand-in for the real thing? Or is it just a kind of methadone, to ween us off the immediate gratification of the swipe-right race that these apps have normalised in the last decade? The answer depends who you ask, with some positioning their spin on virtual love – upload the background of your favourite restaurant! Eat together! – as a temporary substitute for reality. While others, freed from the sense that every message sent is just a step closer to interacting physically, have embraced the potential of digital dating. Tinder and Bumble have widened their distance filters to nationwide or global respectively, so you can date people you are unlikely to ever meet. It's like a kind of global voyeurism, where you can chat with strangers on the other side of the world, like a modern day update of the chat rooms and cybersex of the Nineties.

In her 1998 book Online Seductions: Falling in Love With Strangers on the Internet, psychiatrist Esther Gwinnell argued that the internet romances her patients had formed were "uniquely intimate" because they "grew from the inside out." The pitfall of this was that, when bought into reality, "The cyberlove of your life could turn out to be little more than a mirage or a private psychosis."

Whether it's possible for romances that have been born into, and played out, in private digital correspondences to have the same intimacy in real life will become clearer as coronavirus lockdowns ease. Dating is, after all, about to change yet again. We might embrace the 'vibe check', which Bumble, Hinge and other apps hope to facilitate via video calls, as a natural part of the vetting process. Dating, already Uberised, could be made even more efficient courtesy of a Netflix-alike preview.

In a New York Times piece titled 'The Tyranny of Convenience', Columbia Law School professor and writer Tim Wu dismantles the presumption that convenience is always good, arguing that we should not embrace it as a general rule. "The dream of convenience is premised on the nightmare of physical work. But is physical work always a nightmare? Do we really want to be emancipated from all of it? Perhaps our humanity is sometimes expressed in inconvenient actions and time-consuming pursuits," Wu writes. "Today’s cult of convenience fails to acknowledge that difficulty is a constitutive feature of human experience. Convenience is all destination and no journey."

The convenience of virtual dating is alluring when it promises you won't have to wait for a night bus at the end of a bad date, or worry about being stuck with someone nursing their pint while you want to leave. It's less attractive when it means you might miss out on a stolen kiss by the train station from someone you dismissed in an app, because they didn't know the capital of Hungary. It risks us missing out on experiencing some of the human aspects of attraction: the way someone smells or walks, or whether they also interrupt you without the buffering awkwardness of a video call to blame.

Dating apps offer an endless carousel of potential matches and put the fate of meeting the one into the hands of the algorithm. The next logical step of this could be spending more time on our phones sussing out the one and perhaps never laying eyes on them without a screen between you. While convenient for the time-poor or those concerned about meeting a stranger, it is a slide toward letting technology further control who we meet which is at odds with the chance nature of human interaction, begging the question of whether you can you really know somebody unless you've met them.

Last week my friend who had abstained from virtually dating the "love of his life" met her for a socially distanced walk in the park, realising as they said goodbye that whatever had been there a few months earlier had faded away. He wasn't sure whether virtual dating would have kept it alive or made him realise it wasn't right sooner. Either way, he was relieved he didn't have to call it quits over Zoom.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts