Your eyes un-gum at cock’s crow, and there’s a bleary view of dawn through the dormer window: you may be a knight of the realm, but you’re a pretty damn lowly one, so your room is in the attic of the Le Grand Commun, the building the King has allocated to those nobility who, at his command — and dependent upon his sinecure — are permanently resident at court.

It may be early, but you go straight from languor to ardour. And for what? Not the nubile coquette sprawled beside you in the lit bateau, whom you waltzed away from the festive fun late last night; and chased, laughing, between, the fountains bubbling with Champagne, but preferment, of course — because at court, all is preferment, achieved principally by taking your place in the long, long looping line of nose-to-tail flattery that shackles each preening, wannabe great lord to the next in a perpetual, shit-eating chow time.

Speaking of which, you better shake a leg in your piss-pot, my lad, and look lively: the King’s levée begins as soon as he awakes, and his celestial majesty is often up before the sun he honours by taking its name for his own sobriquet. Up before the sun, after dancing the night away — although well into his forties, and so late middle-age, it’s only a few years since Louis gave up performing publicly, dancing himself in the masques and massed ballets that are so much a feature of this, the most showy and demonstrative court in the history of Europe, and perhaps anywhere else.

In private, you’ve heard, he still struts his stuff — and out-struts tout le monde de la mode. To attain that privacy — and the yet greater preferment that comes with it — you’ve got to be in the right place at the right time to be able to, say, hand the absolute monarch the silk-swathed batons with which he wipes his regally invincible arse. While to be the one who can’t even gain access to the antechamber from which the font of all sublunary justice and mercy is to be seen at stool is to risk the very antithesis of preferment; to wit, ridicule.

So, look lively — but look fashionable, too. Obviously, not being a noble of the blood but merely a scion of a minor, recently created peerage, you have no entitlement to wear red heels, let alone the blue-silk and silver-lace jackets the King has recently introduced for senior nobles. But although you may be feeling slightly rough, at least you no longer have to wear one. Wigs are, however, on the point of coming in — in line with the Monarch’s own receding, um, hair-line. No: the sumptuary laws that marked the Medieval period have by and large disappeared: nowadays, a man may wear more or less what he wants; and in so doing, perhaps — quite without meaning to — give the impression that he’s of a rather higher status that he is in reality.

It may only be the late 17th century, but the lifecycle of French fashion is already well established: new looks appear and are modelled at Louis’s all-singing, all-dancing court; then are adopted by the so-called grand bourgeois in Paris, followed by the provincial nobility. Soon after that, every cheap little small town madame and m’sieur is getting their local dressmaker or tailor to run them up a copy, and the quality all have to change.

But into what? Luckily, help is at hand —and since you’re one of the first subscribers, in between your own toilet and the King’s, you should have time for a quick cup of newly fashionable hot chocolate (the Queen’s mad for it!); together with a speedy perusal of the first edition of the Mercure Galant, the world’s very first style magazine, which is being published right here at Versailles.

You had a riffle through the thing when it arrived yesterday. It’s a chunky little bound volume some 300 pages long — but with only 40-odd words on every page. Some of them are very odd — I mean, what possible interest could you have in reading Madame la Marquise Deshoulières’s letter in verse to Monsieur le Comte “LT”, on the vital subject of — I shit you not — worming her pet spaniel? There’s quite a bit of this sort of stuff — the rich and notorious showing off in its pages for each other’s benefit. If they could have pictures made of their new baroque chateaus in order to impress and amaze, they would. More substantial are offering by Racine and Molière, whose business is writing rather than merely bons mots.

A piece on the new medicines being made for the King — and presumably taken by him— is of more interest, as is one on his official and personal seals. Obviously, you need to keep up with the news of diplomatic and military appointments — many of which are also generous sinecures with little in the way of actual duties attached. But the items that really caught your eye yesterday, and that you resolved to thoroughly peruse, were reviews of new books on gallantry — which, in this era, means everything associated with the arts of seduction, whether personal, political or purely prurient— and a comprehensive round up on “new fashions, both in clothing for one and the other sex, and for furnishings”.

Not that dressing a table and a body are precisely the same undertaking — but they go together in the elite European culture of the late 17th century; while then — as, arguably, still now — Paris is the centre of that world, together with the luxury goods it craves. Anything up to a third of waged workers in theParis of this era are engaged in the business of clothing and cloth in one way or another — whether it’s as relatively unskilled seamstresses, or in the rapidly expanding Gobelin tapestry works, established by the King, where the finest textiles are made for both domestic consumptions and highly profitable export.

Yes, the Sun King’s court — as the equally luminous Susan Sontag will point out in some 300 years, in her seminal essay on the subject —was above all things the crucible of that aesthetic sensibility that came, in the 19th century, to be called dandyism and, in the 20th, camp.At Versailles, Louis XVI fused the desperate seriousness of political absolutism with the easeful triviality of dressing up and putting on a show. For the first time in history, preferment became purely a matter of the performative.

Which is why it’s so vital you’re aware young men are currently wearing their hats much bigger, and with many tassels, much to the chagrin of their elders. Gold lace bands are in — red ribbon ones, emphatically out. As for women’s clothing, this, too, you need to take a professional interest in — in a world where the monarch appears literally encrusted with gold (he received one ambassy wearing a jacket estimated to have weighed 20 kilos, it was so gilded and bejewelled), a gallant has to be as able and willing to discuss the pros and cons of silver-embroidered overskirts as he is the latest campaign to subdue the pesky, puritanical, plain-dressing cheese-heads to the north.

In a few years’ time the Mercure Galant will be carrying engravings of those big new hats with their gold-silk ribbons. It will continue being published down the decades and through the revolutionary years, only briefly repressed under Napoleon. At some point it changed its name to the Mercure de France, and it’s in this guise that the once-scintillating herald of the style-eras-to-come subsists in our own. However, it isn’t a style magazine anymore, but a vaguely trendy imprint of the august publishing house Gallimard.

This is how the Beau Monde ends: not with a bang, but with a hipster.

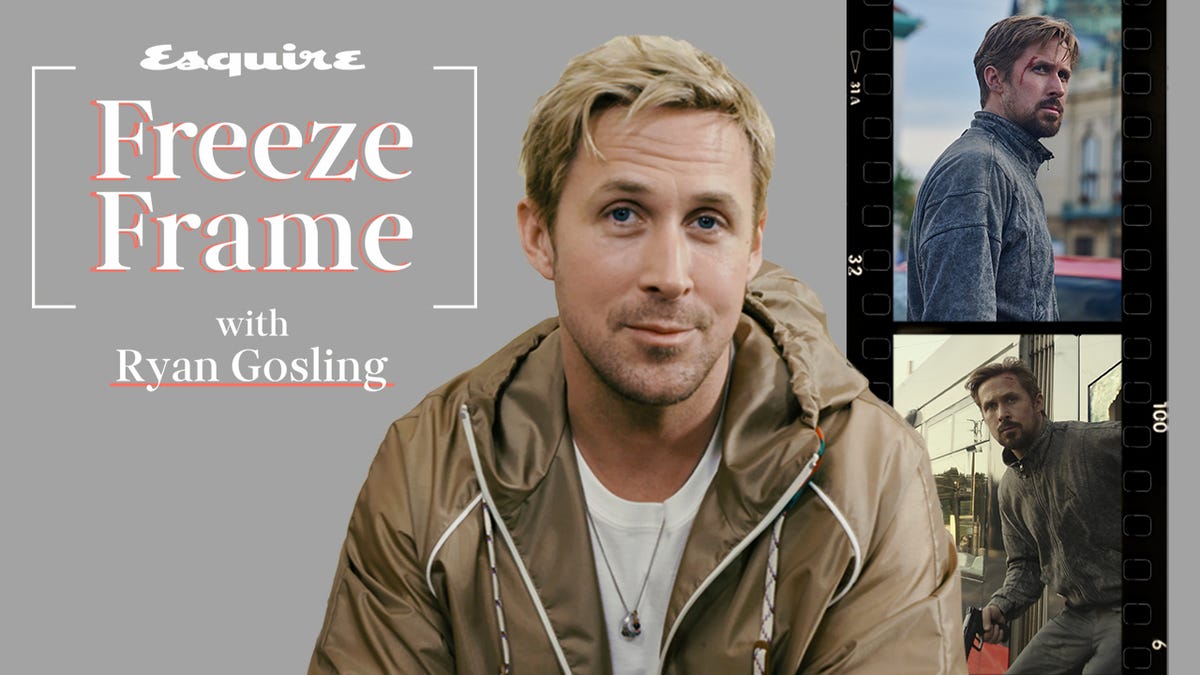

Will Self is an author and Esquire editor-at-large, most recently of the essay collection Why Read. This piece appears in the Spring 2024 issue of the magazine, out now