In her 2009 autobiography, Fragile, published three years after she appeared on Big Brother 7, Nikki Grahame wrote, “I'd never felt special in my whole life before Big Brother. I'd never felt I fitted in or belonged anywhere really until then. But finally I did.” Twenty-four years old when she entered the house, Grahame had been working in Harrods as a skincare specialist. “I just wanted to turn my life around and do something extravagant and exciting and go on an adventure,” she tells me. “There was nothing bad in my life at the time. I just wanted more, you know?”

This was the allure of Big Brother: that it could 'turn your life around'. Simply by living in a house with a dozen strangers and having your every moment filmed for a few months, you had the chance to become more than you used to be. You could win £100,000, leave behind the drudgery of a day job, and live life as a star, blinded by the light of paparazzi cameras. Grahame had seen it happen to six seasons' worth of contestants before her, and she was one of hundreds of thousands who queued up for some of the same treatment. She didn't even need to win. (She didn't win.) She just needed to be memorable. She just needed to be liked.

Twenty years after the first episode aired in the UK, Big Brother has fizzled out, its last episode airing to poor audience numbers on 5 November 2018. A regularly refreshed snapshot of contemporary Britain, perhaps no single show has had a more profound impact on popular culture. How did a show about nobodies doing not very much come to seduce the world?

The Big Brother story begins in the Netherlands in 1997, where the idea was dreamed up by employees of a subsidiary company within Endemol, the Dutch television production house founded by John de Mol and Joop van den Ende. The inaugural show began on 16 September 1999 and ran until the turn of the year. It was won by Bart Spring in 't Veld, who became a star but would come to resent the impact the show had on his life. “Big Brother took away the need to make inspiring programmes and replaced them with mindless chatter,” he said later.

The launch season of the show was a massive hit, giving Endemol phenomenal viewing figures. On 28 February the following year, Germany followed suit, putting housemates inside for 102 days and attracting record numbers of viewers. Upon his exit, one of the show's early evictees – a Macedonian man called Zlatko Trpkovski – released a single that went to number one in the charts.

In March, a BBC News article heralded the show's imminent arrival on British shores: “A British version of the fly-on-the-wall show which has been a hit across Europe is the highlight of Channel 4's spring schedule,” it said. In Germany the sense of moral panic had been far greater than in the Netherlands: “The country's interior minister, Otto Schily, called on viewers to boycott the show if they 'still cherish feeling for human dignity'.” There may be few greater PR boosts for a TV show than being described by a government minister as morally bankrupt. Big Brother arrived in the UK carrying a wonderful whiff of the taboo.

'Reality TV' was not really a phrase in 2000, says Professor Janet Jones of London South Bank University, who was making 'docusoaps' for the BBC around this time and would go on to co-edit a book about Big Brother. She remembers that in April 2000, at a Royal Television Society talk, television executive Peter Bazalgette described Big Brother as a 'social documentary'. With executive producer Ruth Wrigley he had seen the original version in the Netherlands and decided to export it. “He wanted it to have a serious, consequential dimension,” Jones says. (Declining my request for an interview, Bazalgette says he has a rule: “Look forward not back!”)

Marcus Bentley, who has narrated every episode with his iconic Geordie accent, remembers that there were “rumblings in the papers of this new thing from Holland”. He had splashed out on a recordable mini-disc player and, to record his audition fragments in the spring of 2000, he bought an £8 mic and talked into it, his wife giggling on the other side of their bedroom door. He landed the gig because one producer particularly liked the inflection he gave to 'chickens', the birds that lived in the garden of the custom-made house.

In Big Brother's first episode, which aired at 11pm on 14 July 2000, Bentley's comparatively subdued voiceover explained that the housemates had “no TV, no radio, no newspapers – only each other for company”. The show saw 11 people compete for 64 days to win a prize of £70,000. It was a 'social experiment', and a game show whose currency was popularity. The house had 26 remote cameras, 36 microphones, and five manned cameras. “Big Brother is always watching,” Bentley said – a line from George Orwell's novel 1984, a debt the producers have never acknowledged.

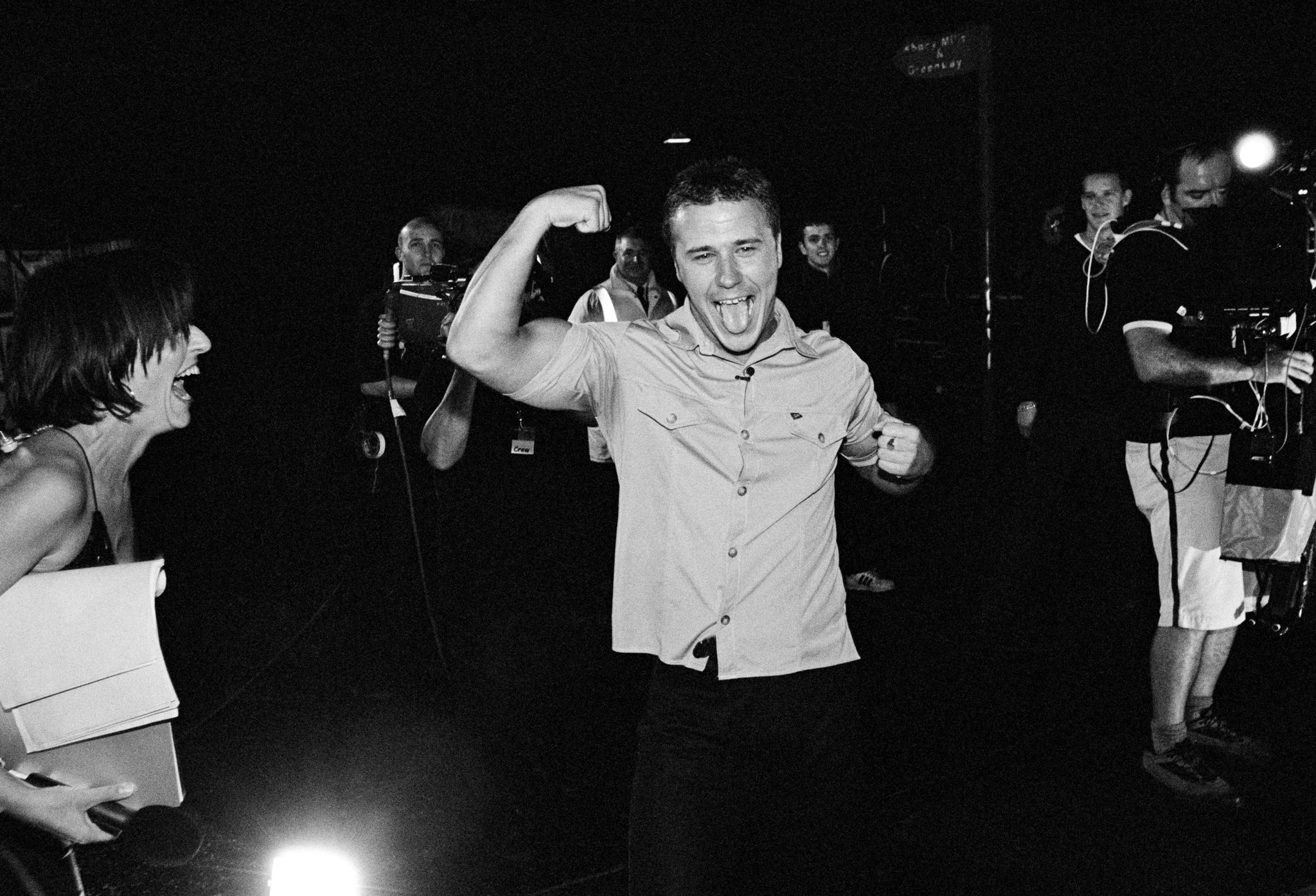

In comparison with the histrionics, gimmicks and bright lights of later seasons, Big Brother 1 is muted, tame and sweet. Eventual winner Craig Phillips, now an after-dinner speaker and celebrity DIY expert, tells me, “I honestly sat on that couch every day, thinking to myself, how on Earth can anyone make a TV programme about this? And I couldn't have been any wronger.”

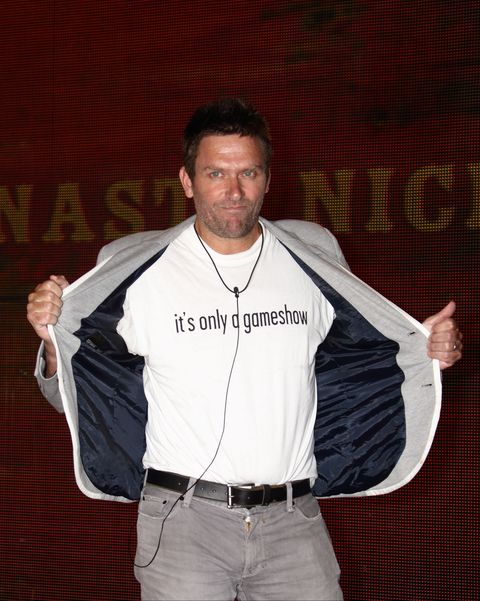

To this day, no series can rival the first for infamy. In a pattern that would continue, the most memorable contestant wasn't the winner; it was Nick Bateman, whom the world would come to remember as 'Nasty Nick'. Bateman told strange lies to housemates, like that his fiancée had died in a car crash; he discussed eviction nominations with housemates – explicitly against the rules; and he was suspected of having smuggled a phone into the house.

“We would go stand in the camera runs and just keep an eye on him and see whether he'd hidden anything in his suitcase,” says Paul Osborne, who was a producer for eight series. “Turned out it was just paper.” Jonnie Kinder, who worked as an editor during this period, remembers having to watch Bateman under the covers to ascertain whether he had a pager or phone. (As there is a sacrosanct rule that the production team don't intervene in housemate affairs, they could not simply walk into the house and ask him.)

Though Bateman hadn't packed a phone, his attempt to manipulate housemates by discussing nominations with them was a clear breach of the rules. “I've never had so many text messages; so many people emailing, trying to ask me what was going on,” says Osborne. Kinder remembers journalists approaching the editorial team and telling them that their publications had been receiving death threats for Bateman. “We were like, 'Oh my God – what have we done?'” Bateman was disqualified, but not before his fellow housemates staged a confrontation, demanding to know why he was cheating. Janet Jones considers this one of the ten most seminal moments in the history of British television. For the show, it was a godsend.

After Bateman was ejected, his fate was uncertain. “There was a visceral feeling of 'What is going to happen to him?' because there was such a fever around it,” says Osborne. “You'd never seen a person from a television show who wasn't a celebrity in any way be so fascinating to the British press.” Like countless other contestants, Bateman exploited his persona and, among other things, released a book called Nasty Nick: How to Be a Right Bastard. Bentley remembers the front page of The Sun running a photo of the ex-housemate next to Brad Pitt, Vinnie Jones and Guy Ritchie. The headline told you everything you needed to know about Big Brother's status: it said 'Who's with Nasty Nick?'

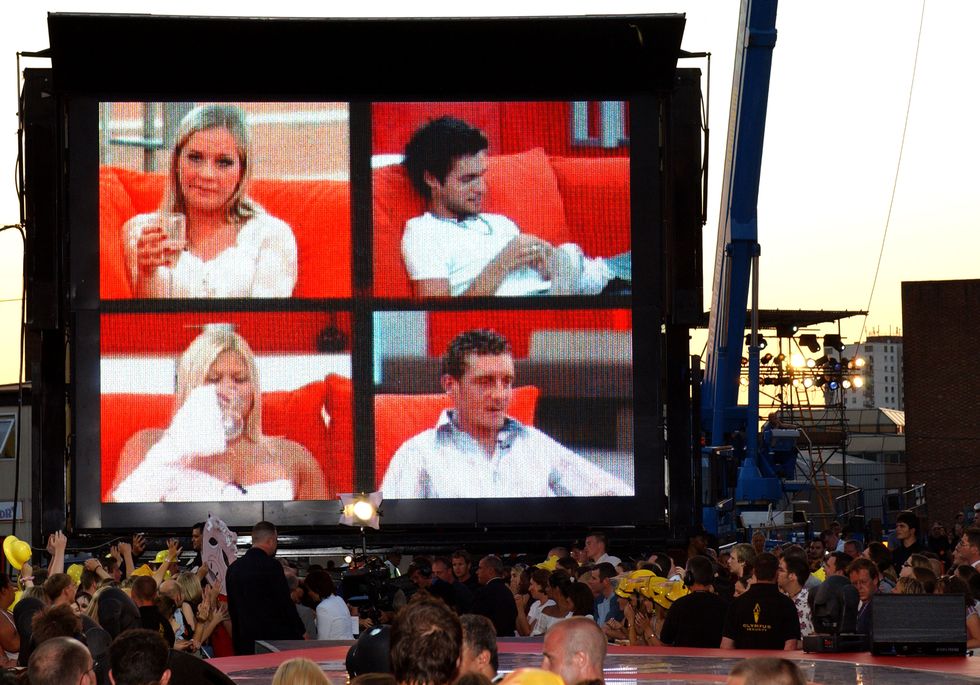

Around ten million people watched the first Big Brother final. Eviction nights, and the final in particular, were colossal live events. “For a second, as they opened the door of the house, they could hear the crowds cheering and booing and hissing,” says Jones. “And after four or five weeks suddenly they started talking about the fact that maybe people were really watching this programme.” Everyone I speak to talks about the first series, which won an Innovation Award at the BAFTAs, as a time when contestants were innocent and unsullied by expectation. However, there is a risk of being seduced by a false nostalgia. As Bentley says, in its first week “most of the housemates got completely stark-bollock-naked together, had a mud fight, rolled around in the mud together, and then had a naked shower together”. Many of the people I interview talk about contestants in subsequent seasons simply applying to become famous. In the first episode of season one, however, Nicola, one of the contestants, looked at the camera and said, “I applied for Big Brother 'cause I want to be famous and I also wanna be rich.”

Big Brother didn't come out of a vacuum. In the US, The Real World, which dated back to 1992 and is still running on Facebook Watch, lumped strangers in a house together and recorded what happened. Survivor, which began life as Expedition Robinson in Sweden in 1997, saw contestants living together on an island and each being eliminated until a victor remained. (Castaway, the production company responsible for the latter, unsuccessfully sued Endemol for Big Brother being too similar.) The first person voted out of Expedition Robinson then died by suicide a month afterwards – a risk that would come to dog every similar reality TV experiment. In 2006 a Big Brother contestant left the show after threatening to kill himself, and in 2009 an evicted housemate slashed his wrists while watching the programme.

The contemporary coverage of the first season is alarmingly unpleasant, even in the broadsheet press. Writing for The Guardian, Emma Brockes called the contestants “a hideous bunch” and said that Phillips wasn't a “humble labourer” at all, but the owner of a building business that employed a dozen people. (In literally the first clip we see of Phillips, he says, “I'm a self-employed builder and actually employ twelve people.”) Paul Osborne points out that the show was unusual in that it featured working-class people. And, as series two winner Brian Dowling tells me, the show allowed you to see people you wouldn't normally see. Nadia Almada, a trans woman, won series five, during a time when trans people would have been on the radar of barely any viewers.

For the 2004 book Big Brother International: Formats, Critics and Publics, Janet Jones worked with Ernest Mathijs to analyse the versions of the show in various countries. In every iteration, a camera featured in the opening credits. Mathijs says that the fascination with surveillance technology is key to understanding Big Brother's appeal. “The show is saying, 'This is not just a contest. This is not just an examination of who's best in living with others in isolation. No. This is a contest about who lives best under surveillance.'”

Mathijs points out that the reaction to Big Brother was like the reaction to a horror film: initially people were curious; then they were revolted; then, as they learned the rules, they defended it. “The moral question about whether this programme should be allowed to survive was huge in 2000,” says Jones. “A lot of people didn't even watch it at the beginning, they just liked to talk about how awful it was.”

One of the most important things Big Brother did for television culture, Jones thinks, was make TV only one aspect of the show. It cultivated a web audience by streaming the show online with a delay of just 15 minutes. This online audience was crucial for Jones when she posted a questionnaire on her university site and on the Big Brother site, receiving more than 60,000 responses. Asked why they liked certain contestants, people tended to say that they seemed 'genuine' and 'normal'. If they disliked them, it was because they were 'scheming' or had 'a fake personality' or were 'unattractive'.

Psychologist Daniel Jones watched the show for hours a day and spent a lot of time on Big Brother forums, remarking on housemates' behaviours. He went on to write The Psychology of Big Brother, a book about his observations. He points out how little control contestants had in the house: “You have lights come on and music playing when Big Brother tells you you're waking up; you have food when Big Brother tells you you're having food...” He mentions a study carried out on prisoners of war, in which those that survived longest were those who, among other things, exerted the most control over their circumstances – counting to five before they screamed, for example. In the Big Brother house, some people would achieve that sense of control by ignoring Big Brother as much as possible. “They can't control whether they have to go to the diary room but they can control when they choose to go to the diary room.”

Why did certain people win Big Brother? When I ask Kate Lawler why she thinks she won series three, she says, “Erm, because I'm a fucking legend?” Treating it more seriously, she says that perhaps the public, having crowned a straight man then a gay man champion, thought it time a woman won. Mathijs points out that winners tended to be those who didn't cause much controversy but who weren't boring enough to be evicted. One of the classes he teaches at the University of British Columbia looks at the difference between a star and a celebrity. “Big Brother was definitely a pioneer in putting forward the idea that all you had to do – and this is important because Facebook picked this up later – all you had to do is be liked.” All of a sudden, celebrities were ordinary people whose lack of talent was less important than their popularity. Mathijs says that the show asks to what extent likeability is a performance. “I think we still haven't found – and perhaps we shouldn't find – an answer to that.”

Because the show was a televised popularity contest, the potential damage to contestants' mental health was always a concern. The arduous application process (Lawler says that she applied largely because her twin sister pulled out after seeing how many pages she would need to complete) included a few meetings with a psychologist in order to decide whether contestants could handle the uniquely weird experience. Two years before she was accepted, Nikki Grahame had applied but, in one of the numerous conversations with producers, told them that she had had anorexia. She feels sure this was why they turned her down. She waited until the production team changed, applied again without mentioning the anorexia, and qualified.

When I ask how Endemol prepared contestants for Big Brother, no one speaks ill of the company (though Phillips says that “many many others certainly didn't get the after-care I got”). But mental health professionals have been fiercely critical. Daniel Jones questions the ethics of airing footage that producers knew would cause a backlash for the person concerned. The point of no return for Big Brother is widely believed to have come in 2007 when Jade Goody, series three finalist and arguably the most famous contestant of all time, returned for Celebrity Big Brother 5 and became involved in racial abuse of actor Shilpa Shetty. Goody “got a lot of backlash because of something that was aired that could just easily have not been aired,” Jones says. While true, this would run counter to a central intention of the show, which was to place in close proximity people likely to rile each other up. The footage of Nick Bateman saw him vilified in the press but would it have made any sense not to broadcast it?

When Goody was in the house originally, unbeknownst to her, the media vilified the 20-year-old for various perceived faults. “That was hard,” says Osborne. “She was young, so there was always a concern about how she'd feel about that.” The production team couldn't talk to Goody about the media coverage – this would have “spoiled her experience”, says Osborne – but the welfare of the housemates was constantly monitored, and a producer would talk to them if they were worried. Jonnie Kinder says of the housemates, “I did sometimes feel a bit guilty, really, because you are using them as a commodity … I remember discussing it with my boss and he was like, 'Well, they've signed the contract.'”

Before a new series began, lawyers would meet with the producers and remind them of their obligation to present events as they occurred. “We never made anyone do or say anything they hadn't,” says James Moriarty, who worked as an editor from 2013-16. “ We never twisted anyone's words.” One anonymous director tells me that it was on his conscience that everything he presented was accurate. He never thought the footage had been edited unfairly. “I've certainly seen it on other shows that I've worked on since,” he says.

Indeed, one cannot underestimate the influence that Big Brother had on these subsequent reality TV shows. Without Big Brother, today's TV landscape would look markedly different. One of its legacies is that it gave power to the viewer. “Who goes? You decide,” Bentley said every week. Shows like Strictly Come Dancing, The X Factor and Britain's Got Talent would all come to follow Big Brother's lead in this respect, putting the audience in charge. Mark James, who worked principally on Celebrity Big Brother, says that programmes like Love Island and I'm a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here! wouldn't exist if it weren't for Big Brother. Moriarty says that, as the show migrated to Channel 5 in 2011, the process came full circle and the show was shaped by other reality shows: its pace increased; it featured more musical montages. In Kinder's opinion, the show became less concerned with faithfully presenting events. As programmes like The Only Way Is Essex (2010) and Made in Chelsea (2011) pioneered a format known as dramality – staging their 'real' moments to an extent that early Big Brother wouldn't have considered – the show began to try to follow suit, changing the show perhaps to appeal to fans of these competitors. “It became less of a social experiment and more of a reality show,” says Moriarty. It had lost what had made it Big Brother.

To observers, the show had had its day. In 2017, for the first time ever, Big Brother averaged fewer than a million viewers. “The problem is, they kept on trying to be more dramatic and more stupid and more eccentric and more amoral,” says Janet Jones. “In order to keep the high going, they had to keep on doing horrible things.” Daniel Jones says that the show was more exciting when it was less editorialised: in the Channel 5 era, he says, viewers were spoonfed one storyline, as opposed to being allowed to pick up on housemates' small behaviours, glances, and comments. Channel 5 also did away with the live feed, sacrificing a defining element of the show. The channel interfered too much, says the anonymous director, making “very last-minute snap decisions” and saying things like “We're now not doing this eviction tomorrow, we're gonna put four people in instead.”

But the other change that people impress upon me is that contestants began to enter simply to become famous. The show almost created its own “type of person”, says Kinder – someone who wanted the fastest route possible to celebrity. Their fame was often “quicksand fame”, says Janet Jones; of the 327 UK contestants, only a handful – notably Alison Hammond, Brian Dowling and Kate Lawler – now have what could be described as a high profile. Bentley benefited from the world recognising his voice, and once recorded a message for the funeral service of a dying fan, in which he told her that she had been “evicted from planet Earth”.

Nikki Grahame, infamous for her diary-room outbursts, says that housemates began copying this behaviour in a cynical attempt at notoriety. She also says, “People suddenly thought if they had a romance they'd get loads of work and media. So it became a little bit repetitive and the novelty wore off a little bit, I think.” Dowling says, “I always think that Big Brother kinda created celebrity culture. It does make you famous but it may just make you famous for that summer. Being famous isn't everything. There's also a dark side to it.”

Lawler, unusual in admitting she knew the show might make her famous, remembers the immediate aftermath of her win. “People used to come up to me and say, 'I watched you sleep.'” A camera crew followed her around, making her check her bank balance for viewers to see. Having won the £70,000, she was revealed as owning £70,250. She thinks that everybody prior to season five had no idea what to expect. But after that, people expected to be as financially successful as Goody or Hammond. “All of a sudden you had more housemates not getting what they wanted out of the experience.”

In among the show's burning embers, however, were some wonderful moments. In 2005, the first celebrity series for which housemates were paid to appear, model Brigitte Nielsen watched her ex-mother-in-law Jackie Stallone enter the house. “Oh my God, Jackie!” she shouted. “...Yeah, Jackie,” Stallone said nonchalantly. Mark James was a runner for this series and remembers having to stand in the camera run on one side of a two-way mirror and check that 83-year-old Stallone, who slept in a separate room and barely moved when she did so, hadn't died. For Big Brother 7 James was a chaperone for contestant Mikey Dalton. This meant, just prior to the show starting, travelling with him to the south of Belgium, away from the press. Every day he'd get a call from a casting producer telling him if any names of prospective housemates had been leaked. If they hadn't, he and Dalton could leave the house they were staying in. They kayaked together and had a day out at a Belgian theme park.

2016's Celebrity Big Brother 17 saw a hilarious moment of astonishing chance. With David Bowie having died the day before, the producers broke the news to Angie, Bowie's ex-wife. She then told television personality Tiffany Pollard. But in breaking the news she didn't say, “My ex-husband David Bowie has died”; she said, “David's dead.” This was ambiguous, given that one housemate – asleep in the bedroom and therefore unable to pipe up – was David Gest. Assuming that a fellow housemate had dropped dead, Pollard began shrieking and clutching Bowie for support. She was even more upset because Bowie told her not to tell any other housemates. It is one of the funniest moments ever broadcast on television. Ben Hardy, then a director on the show, wasn't sure it was ethically all right to air. “And actually, when I watch it now, I think, yeah I was actually wrong,” he says, “because I thought it was a very funny moment.”

Twenty years on, it would be impossible to argue that Big Brother hasn't changed the world we live in. Because television is one of the primary media through which people achieve fame, a generation of celebrities – and the notion of celebrity itself – has been moulded by the programme. “Big Brother gave people hope that you could change your life by just being yourself,” says Dowling. This sense of hope, false or otherwise, has fuelled countless aspirational bloggers, vloggers and Instagram stars. A lucky few can make a living simply by 'being themselves' rather than relying on the mastery of a technical skill. Depending on your stance, this has either democratised fame or given a platform to people who have absolutely no talent.

As well as this, of course, it changed television forever. “Everyone's always looking for the next Big Brother, if you like,” says Hardy. In Big Brother's Big Mouth, Big Brother's Little Brother and Big Brother's Bit on the Side, it basically created the spin-off show, emboldening fan culture and giving fans licence to spend their lives analysing the minutiae of other programmes. Gogglebox – a show in which people watch people watching television – would have been laughed out of the room if pitched in the 20th century. But, if the concept works and the people are interesting, we have learned that we will watch ordinary people do pretty much anything. “We're all really nosy,” says Dowling. “If my neighbours argue, I like to listen.” Big Brother was voyeurism, he says – but voyeurism we had been given permission to enjoy.

When I ask Bentley, Grahame, Dowling, Phillips and Lawler if they have ever regretted being involved in the show, each of them says no. But Phillips adds something. Walking down the street, he used to be stopped by people who had applied to be on Big Brother. Unfailingly polite, he would ask them about themselves and why they wanted to be on the show. After they had done so, they would ask if he had any advice. He would always look them in the eye and give them the most honest answer he could muster: “Don't do it.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts