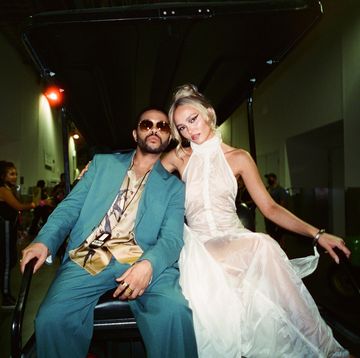

In March of this year, when a group of celebrities recorded a cover of John Lennon's 'Imagine' as a balm to heal the wounds of the pandemic, one of the ragtag group of famous faces condemned by vitriolic YouTube commenters was Labrinth.

A friend had vaguely mentioned getting people together to do "something nice for people going through a hard time", and so he belted out 'above us only sky' in a quivering falsetto while sat in his car. He sent the video file and thought no more of it.

The British singer leant the patchy rendition some genuine musical talent, but for some of those who noticed his cameo – not long after Wonder Woman Gal Gadot's and a few verses before the light leaves the eyes of Will Ferrell – they might have wondered why the singer who had a hit with 'Earthquake' in the UK nearly ten years ago was singing alongside Natalie Portman and Mark Ruffalo.

On the day that the song was released, as it became clear that the "something nice for people going through a hard time" might have needed a bit more brainstorming, Labrinth's phone started lighting up with people asking him why he'd done it. "I thought they had a plan," he laughs over a Zoom call, sitting in a grey jumper in his studio on a damp October afternoon. He has spent the pandemic at home in North London, happy to be given some time where he is allowed to be a hermit and make music. "When I saw it back I was like ‘Oh shit’," he recalls. "I didn’t know I was gonna be around all these cool people but singing such a terrible version of a legendary song. But hey, gotta swallow that pill."

The 'Imagine' video shows the weird space that he occupies: a singer who was initially famous for a specific moment in the UK, but who lives a double life via a more recent, and already illustrious, career in America. Across the pond Labrinth has recently worked with the likes of Kanye West and Beyoncé, as well as winning an Emmy award for the soundtrack to HBO's Euphoria last month. Quietly, assuredly, he has succeeded where so many other British artists have failed. He has made it in America.

What happened to Labrinth?

Google poses this question via autofill when you type Timothy Lee McKenzie's alter-ego into the search engine, and it is one that our discussion naturally arrives at. Ten years ago the musician dominated the charts and picked up awards for his releases alongside Tinie Tempah. Singles including 'Pass Out', 'Frisky' and 'Earthquake' put him at the forefront of a scene where artists like Plan B, Tinchy Stryder and Example made music which bridged the gap between pop, grime and rap.

The success was a strange experience for someone who had grown up messing around with production software at home and never cared much about using music to make money. Labrinth grew up in Hackney, one of nine kids in a family with music at its soul. The siblings, who formed a band together called Mac 9, had the run of the house. "Downstairs my brother had an MPC Controller and another brother had a drum-set so his friends would bring over their guitars," he says. "Upstairs my sisters had their friends singing R&B or gospel songs and working out harmonies. I don’t know how my mum dealt with it because I can’t be around that much noise and I make music."

Despite this very musical upbringing, he didn't dream of being an artist and says he was "the worst musician in his family", instead spending his time drawing pictures and making sculptures. "Then one day my older brother started using this drum machine and I thought ‘fucking hell this feels right’".

Labrinth became part of a community of musicians uploading their music to MySpace, with his friends at performing arts schools taking his demos to record labels to stump for him, and in 2009 he was offered a deal with EMI. "At the time a lot of grime artists were trying to penetrate the pop scene, making stuff like 'Wearing my Rolex', and losing their essence," he says. "I was already working on 'Pass Out' because I wanted to make a grime song that could be played at the clubs."

Though expectations weren't high, the 2010 track which he produced for Tinie Tempah, and also appeared on, went to number one within a week and won both a Brit Award and an Ivor Novello. At the time Labrinth was sleeping on a broken mattress in the smallest room of a house he shared with two friends. "My bum used to touch the floor," he laughs. "It wasn't that I wasn't making money, I just wasn’t focused on it."

'Pass Out' should have given him the confidence to make whatever music he wanted, but the scene at the time was a tug of war between Black artists and predominantly white, out of touch executives, and the compromise resulted in a lot of music that hasn't aged particularly well.

After releasing the single 'Let The Sun Shine' – a song that his grime friends suggested he should "go play to Simon Cowell" (the pop mogul who had by then signed him), but powerful music figures simultaneously deemed as too 'urban' – it felt impossible to please everyone. "I always felt like I never had a home," he says of the liminal space he occupied in the music industry. With "fire in [his] belly," he wrote 'Earthquake' to prove he could make another 'Pass Out'.

'Earthquake' was made for the sticky dance-floors of student clubs, with a sci-fi introduction that gives way to a seismic bass-line and which, like predecessor 'Pass Out', has a frenzied energy to it that made people want to jump. "I played it to MistaJam who was like, ‘Are you ready?’, and only years later I realised what he meant." Labrinth was not ready. Not for the tour of Oceana nightclubs near student universities, where acts like Chase & Status and Kano commanded the stage because they'd been doing it for years, or for the stylists who dressed him in mad clothes, or for the sense that he was suddenly supposed to be a pre-packed brand.

Labrinth recently took a personality test which told him he was the mediator, meaning that he feels the need to please people. When he became famous the anxieties that had plagued his early career – feeling that he wasn't sure what to say, or that it would come out right – came tumbling back in. 'Earthquake' was a success – the phrase "Labrinth, come in", delivered at the opening of the track in a robotic voice, is still something people parrot back to him before letting him inside – but assessing it retrospectively is complicated.

The early Aughts began with the groundbreaking grime of artists like Wiley and Dizzee Rascal, but that soon gave way to a kind of cheesy fusion of pop and rap. "It was shit," Labrinth says, without pause. "Shit music is music that isn’t honest with itself, and that music was lying." People at predominantly white record labels were trying to package up these artists in the same way they were selling the music of X Factor winners. Whereas rap and grime music have bloomed in the UK in recent years, with artists like Stormzy and Dave harnessing the internet to breathe powerful new energy into the music industry, back then it felt like a lot of Black artists had to play a game they weren't in control of and were destined to lose.

"A lot of the label guys were old white men thinking, ‘Would my daughter listen to this?’" Labrinth says. "Now that we have social media you’re getting Stormzy able to be unfiltered and the audience show that’s what they wanted in the first place."

'Earthquake', and his first solo album Electronic Earth, put him in that grey area between pop and rap music, but when trying to write a follow up and capitalise on the acclaim he had earned, Labrinth found himself pulled in different directions by trying to please everyone. He was burned out from touring and his anxiety was mounting and he knew he needed to stop. "Everything slowed down after that: live performances, radio plays," he says. "It challenged my ego because I was famous and if I wanted to go figure my shit out that stuff was going to go away. Do I leave these beautiful things? These linens? This furry jacket? But I had to let it go."

One evening several years later, Labrinth found himself at a party in Los Angeles hosted by an executive of Maverick Records, the sort of party where people like Paul McCartney, Moby, Bono and Jimmy Iovine are in attendance. "It was basically like Madame Tussauds in one room," he laughs. "And I’m just little Labrinth with my glass of red wine and ghetto clothes because I was a nobody there."

Someone from the label announced a special performance from an upcoming artists that everyone had to hear, and then said his name. After spluttering out some of his wine, he sat down at the piano and played them 'Jealous', a beautifully sparse love ballad which left the entire room wiping tears from their eyes. Everyone wanted to know who he was or whether they could sign him, unaware of the career he'd already built.

By this time he had split from his management team and had been going back and forth between Los Angeles and London to make music. He had been writing for artists including The Weekend, Noah Cyrus and SIA, cementing his status as a writer and producer in Hollywood. Starting again in a new town was made more appealing by how his recent attempts at making new music had been received back in the UK, with fans unsure how to react to the guy who made 'Earthquake' now swerving lanes to soulful ballads.

He remembers being so excited about his new music being played on BBC Radio One back in 2014, only to tune into the presenters saying it was "a bit dreary". The British press, too, seemed uninterested in his attempts at a rebrand, and kept calling him "rapper Labrinth" in headlines when announcing that he was making music which clearly wasn't rap.

"If you call 'Jealous' a rap song, are you saying to the audience that are reading an article and seeing a Black guy that they don't want to listen to this?" he says, with weary frustration. "Because if they don’t listen to rap they won’t want to listen to it."

These sentiments have been echoed by singer-songwriter Billie Eilish, who made the point that if she were a Black artist her music would probably be called rap, but because she is white it's allowed to be classed as pop music. As the Grammy Awards have proven time and time again, Black music is too often judged in a separate 'urban' group; allowed to be celebrated in its own category but not permitted to spread its wings in other genres."Lionel Richie is a pop artist," Labrinth says. "But in order to become a pop star as a Black artist you have to reach legendary status. You have to be Beyoncé or Rihanna."

Unlike in the UK, America gave him the space to be an artist without being put in a box, and through his production for other artists his name was passed around Hollywood, making music with Beyoncé for the soundtrack of The Lion King and releasing an album alongside Diplo and Sia. One of the musicians who his music ended up at the door of is Kanye West, who brought Labrinth in to work on his 2019 album Jesus is King. "He's kind of like a high fashion designer in that he keeps incredible talent around him as well as understanding quality music," he says of West. "Your character in the music industry is exaggerated but really all of us are human."

West's music was one of the many inspirations behind the soundtrack for Euphoria, the gnarly HBO series which offers one of the most compelling and least patronising explorations of adolescence in television. Series creator Sam Levinson approached Labrinth having heard the music he was making for his second album, Imagination and the Misfit Kid, because he liked the "weirdness" he was creating.

The Euphoria score is an exhilarating representation of the strange purgatory of that moment where you're no longer a child but not quite grown up yet. From the creepy vaudeville-esque noises of a funfair, a place for children but where adult darkness lies, to the shimmering, fairytale-like sounds that flit through the series, the soundtrack feels like another character that comes to life in front of you. The score features Labrinth singing in his higher vocal register, as well as his family rapping while singing like a choir, as inspired by Kendrick Lamar. The songs conjure a kind of existential dread that it feels wonderful to soak yourself in, one YouTube comments reads, 'This song makes me feel nostalgic for something I never had', another: 'This song makes me wanna do hardcore drugs until I blackout and forget all the emptiness I'm feeling'.

"Euphoria is me with no holds barred," Labrinth says. "It is the clearest version of what I look like musically without worrying about making a hit." The result of his being able to follow his instincts without being influenced by fitting the sound into one genre is an electrifying record which went on to win an Ivor Novello and an Emmy earlier this year. These award nods proved he should trust his gut and come after a lot of soul searching about the kind of music he should make.

Since the house which he grew up in where all you had to do to make a different genre of music was walk up the stairs, Labrinth has wanted to truly explore every kind of music. He wants to be the guy who can play a stirring piano ballad, as well as make Kraftwerk-tinged trippy electronica, or thundering, nervous-making trap. Because he can't really understand why you'd want to keep making the same thing forever, even if it seems to be working out for you.

When we speak again he's back in the studio having had an idea for a song partly inspired by watching his daughter on a baby monitor, though that image will be hidden somewhere hard to find within the song. He's about to release 'Loves Goes', the title track from Sam Smith's new album which deals with the parting of ways at the end of a relationship, and there's also music for the Euphoria Christmas specials on the way, as well as the second season soundtrack which he wants to take on a similarly wild journey.

The freedom to make whatever music he wants has been hard won, especially as a Black artist. "If I’m asked what I do in a cab and say I’m a musician, they will say 'hip-hop or R&B?’, and I think 'shit, did my face say that’s all I could do?' I could make classical music if I want, but the world has given you an idea of what music I make."

Addressing this bias is one of the issues he hopes the music industry tackles as they make commitments to diversify in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests this year. "It’s not just in music," he says. "It’s about readjusting the way society has labelled things and the way we understand race and people."

So what does the future look like when there are so many directions he could take? When I ask he talks excitedly about musique concrète, a type of composition originating from Twenties France which uses recorded sounds of raw materials which are then modified. He also wants to find a way to incorporate late Seventies and early Eighties hip-hop somewhere in his music. There's no talk of needing more awards or, if and when live music returns, wanting to play a huge venue; he just wants to dig into all the weird corners of music he can find. After so long feeling like he didn't know what to say, or that nobody was listening, he knows this is the best way to express himself.

'No Ordinary' is out now via Columbia Records

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts