It’s been a tough year, on that we can all agree. But it’s also been transformative. Amidst the trials and tragedies, there have been unexpected moments of progress and celebration. The Bright Side is a series in which we delve back into the past twelve months and pluck out those positives. Here, Murray Clark explains how video games have helped to fill the void of holidays and festivals.

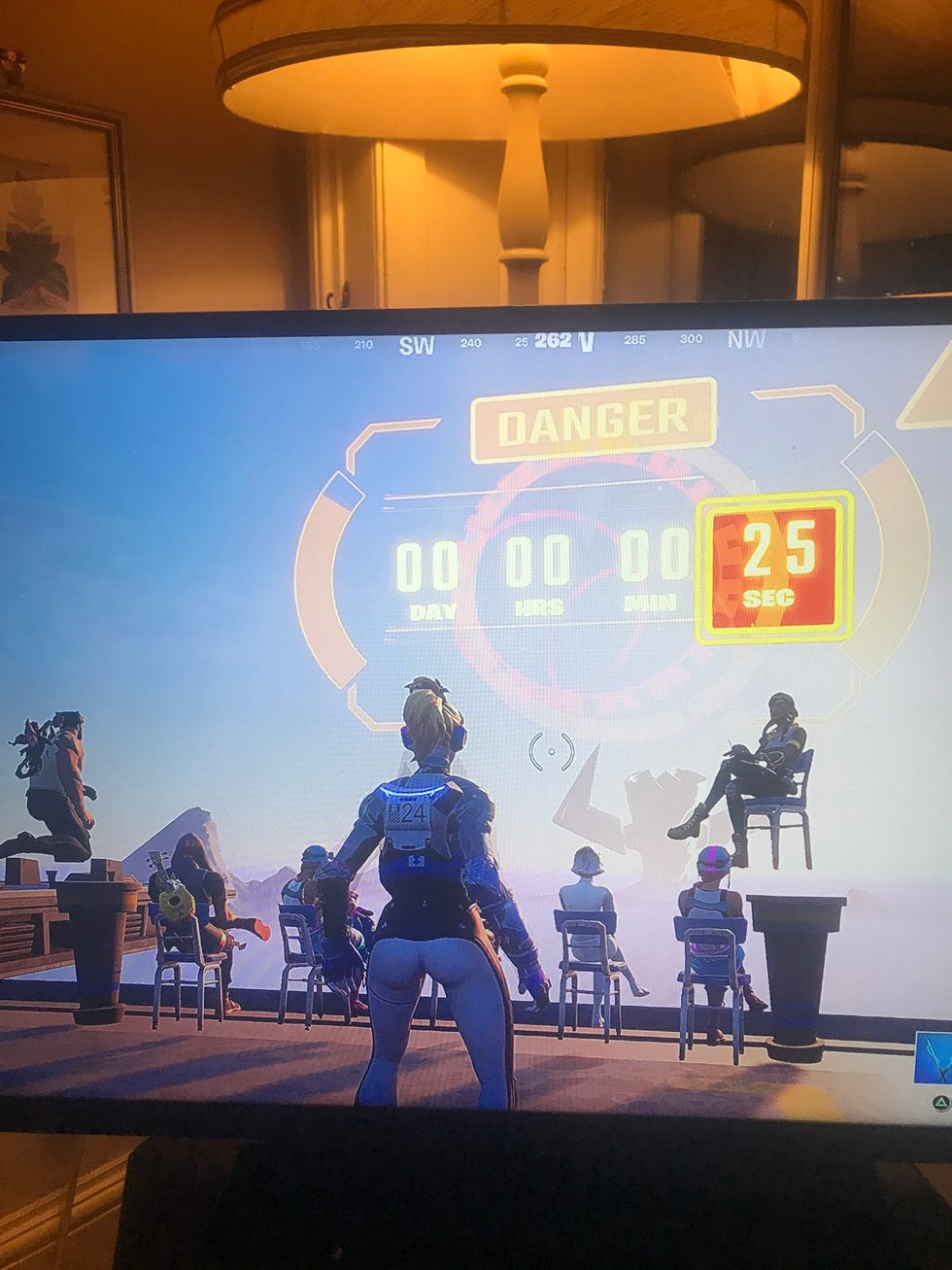

Horizons are different in foreign lands. They’re warmer, brighter. The first five minutes basking in the glow of a yawning, drowsy sun are the most electric. They’re a tangible reminder that you’re not at home, nor do you want to be. And you sit, and you look out in good company, and share a general anticipation of the general unpredictability of such evenings overseas. You might be feasting upon a Dwayne Johnson portion of Italian carbohydrates. You might be throwing back a Princess Margaret portion of gin and tonics. You might do both. Or, like me, you may simply gaze out into the distance as Galactus, eater of worlds and wearer of A-level design headwear, closes in to consume your planet, and destroy your universe. Only I (and cherrywaves11, and signori__smeagol, and countless others) could stop it.

This wasn’t the usual summer holiday. We weren’t wasted by 7pm in the middle of the Côtes du Nôwhere. Lockdown had put an end to that, like everything else. I hadn’t even left my living room. Instead I’d switched on my PS4; a return to a teenage ritual that had become something of a habit in These Strange Times. That doesn’t mean a bad habit. Unlike the all-consuming angst brought on by countless bottles of red wine (which had been furiously consumed because of too much uncertainty), this felt more soothing. Wholesome, even. I felt peaceful. And, yes, sessions were usually paired with sweets, crisps and the occasional joint – another crutch of adolescence – but I didn’t feel guilty about it. In fact, Fortnite (and a very long ethernet cable) was just what I needed.

It’s what 15 million others apparently needed too: the total number of players that logged into the Marvel-themed finale of Fortnite’s fourth ‘season’ (the term Epic Games applies to an episode of its ongoing battle royale shooter), with each climax culminating in a one-off event wilder and more immersive than the last. This focus on delivering a mighty one-time-only experience is perhaps one of the reasons why Fortnite has been a success even in non-Covid times. But its triumph as a video game has been magnified by the pandemic, and it's something shared by the wider industry as both new and old gamers pick up their controllers. According to market and consumer data company Statista, the video game industry is set to make a whopping $159.3 billion in revenue by the end of 2020 – an increase of just under 10 per cent year on year, and almost double that of the uptick between 2018-19.

It’s not just a case of bored losers with nothing else to do. There are actual positives here. A study by the University of Saskatchewan found that video games could encourage a raft of benefits – especially during periods of self-isolation – with subjects noting reduced stress and improved mental health. Regan Mandryk, a lead professor on the study, took to CBC to argue that games “allow you to connect with other people and work together toward a shared goal, or compete in a friendly environment [which] also has lots of benefits for helping you socialise.” Important, especially when socialising is off the menu. “It allows you to escape psychologically, have a little psychological detachment from what’s going around you. It helps you relax. It helps you feel like you’re mastering challenges and it helps you like you have control over your environment – which are four main pieces to help you recover from stress.”

Moments of boredom had always been quelled with a quick WhatsApp and the booting up of a headset. At the outset of summer, when lockdown was at its most Alcatrazian, it didn’t feel much different. Here I was, at my parents, stupefied by extended annual leave that was supposed to be spent in Miami. It was the endless tedium of school holidays all over again. So I went with the familiar balm; my best friends and I spending hours on Monster Hunter: World, trapping dinosaurs, collecting armour and still laughing, 15 years later, at my general ineptitude with anything that requires a nimble finger. Teenage fury had mellowed in recent years as our hormones levelled out, but I could still feel a twinge of annoyance over the headset as we lost, again, to the towering Savage Deviljho, its snapping, dripping, crusted jaws a reminder that games were still really fucking difficult, even on the cusp of 30.

This shared experience is unique to video games. You can’t digitally replicate this camaraderie elsewhere. We had Houseparty: the drop-in-and-out Facetime app that allowed for eight people to scream over one another before ending the night in a conversation with an unknown Moldovan family. Then the party tailed off. So we looked to Zoom, guffawing over cocktails with friends and colleagues as someone froze, Edvard Munchian, kneecapped by the rural wifi of their parents’ house. Then the buzz wore off. So we tried phone calls, letters, new hobbies, IRL conversations even though there was nothing to converse about, anything to mimic the social life we enjoyed before everything shut. But you can’t. Most apps, no matter how complex or colourful or innovative, fail to mimic the rapport and the rituals of a group of friends, formed over years like coastal stacks in a sea of shared experiences and scathing in-jokes. You can’t replace a conversation. Zoom is no substitute.

Video games were never built to replace something. They’re not board games for kids of the Microsoft age. They’re not films. They’re not music videos. They’re not books. Instead, they’re a blend of everything; virtual realities – hundreds of thousands of them – that are perhaps the only way to truly leave the Earth we inhabit and the circumstances placed upon it. Video games give you a place to disconnect from the real world to save an imaginary one. Or, thanks to the rise of the Internet, you’ve a dimension exclusively cordoned off for your friends, another place to carve out rituals and behaviours and personal jokes. With pubs shut, millions took to Animal Crossing instead, turning a pastoral island into their own little paradise, be that a place to gather with friends, a campaign stop for Joe Biden or even a space to showboat in the archival Yohji Yamamoto you never got to buy in real life.

It's not so difference to our spot in a suburban loft conversion, each of us whiling away the hours hunchbacked over PlayStation controllers. When headsets came along, it was a ritual we could enjoy alone, and yet we'd still connect in exactly the same way. We weren't performing on a Zoom call trying to flog a dead horse. This came naturally. We'd always done this.

And, though more lockdowns may be dotted along the horizon in the new year to come, I know, that despite being shut in my house for an indefinite amount of time, I won’t feel too isolated. I’ll miss the pub, and yes, I’ll miss dancing, and I’ll miss the heavy arms that are thrown over shoulders on the way back to someone’s living room. But I’ll be able to sit in my own, on my own, staring out at another Galactus in the sky that's begging to be taken down. I won't do it alone.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts