It’s been a tough year, on that we can all agree. But it’s also been transformative. Amidst the trials and tragedies, there have been unexpected moments of celebration. Changes that could and should outlive the pandemic. The Bright Side is a series in which we delve back into the past twelve months and pluck out those positives. Here, Murray Clark explores the confusing world of K-pop fandom.

It was the summer of 2014: my very own Bryan Adams odyssey. Except I was in Bangkok, not small town Idaho, and I was mainlining cheap, headache-inducing beer in the sort of sweltering bar where the very walls seem to perspire. An old school friend who had recently relocated to Thailand was playing tour guide. We saw several sights, and stopped at several dives on Sukhumvit’s Soi 11 side street. I don’t remember seeing that much. But as we litigated our scholastic transgressions in that packed bar, a TV – the sort that appear to be a metre long in the rear end – flickered into life. Nine young women, all identically kitted out in very flammable, metallic burger van outfits, danced in perfect unison, robotic voices belting out a diabetically saccharine tune about flowers. Three girls across the bar began repeating it, word for word, arms in the air and voices decidedly less robotic. “What’s that about?” I asked/slurred, nodding towards the trio who were now co-opting the corridor to the toilets as an impromptu dance floor. “Girls Generation,” came the flat reply of my tour guide as he glanced at his phone. “K-pop. It’s a big thing man.”

Fast forward six years and A Big Thing became a titanic one. Where revenue for physical music sales declined in much of the world, it’s on the increase in South Korea. A report published by the Korea Creative Content Agency found the industry to be worth at least $5 billion – and it is no longer just confined to the Asian continent. Millions of fans worldwide now stand under the wide umbrella of K-pop, a loosely-named genre that can encompass elements of pop, rock and hip-hop in a candy-coated, high energy, heavily dance-routined package. BTS, arguably the current crown princes of South Korean music, broke records when their music video to ‘Dynamite’ scored more than 101 million views in just 24 hours.

Of course, their fans are fanatical. That’s not a new phenomenon in popular music. But these fans are also activists. They organise online in the hundreds of thousands under progressive banners, administering a show of force so large and impactful that it’d put even the most robust social change bodies to shame. “K-pop fans aren’t just K-pop fans. It’s not a binary; that’s dehumanising,” Billboard’s pop correspondent Tamar Herman told Time magazine earlier this year. “It’s not just K-pop fans who are doing this. It’s Black people who are K-pop fans who are doing this, it’s allies who want to support Black Lives Matter who are K-pop fans who are doing this.”

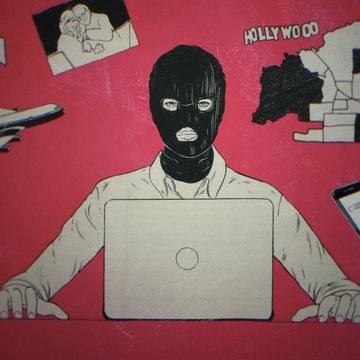

The pandemic has presented the act of protest with new logistical problems and risks. Not so for the K-pop hive. Twitter, Facebook and TikTok are the most popular – and visible – platforms for safe, socially distanced operations, but efforts extend to chat app Discord and even livestream gamer go-to Twitch. During the Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, K-pop fans mobilised online to donate significant sums of money, and to hijack efforts that aimed to subdue the movement. When the police department of Dallas, Texas encouraged members of the public to send videos of “illegal activity protests”, K-pop fans flooded the specially-developed app with fancams of their favourite stars in such a number that screening submissions was an impossible task. Where counter hashtags #AllLivesMatter and #WhiteLivesMatter soared to the trending spots of Twitter, the message was polluted, again, with thousands of fancam videos. And even US representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the darling of progressives worldwide, gave a full-throated endorsement of K-pop fans for sabotaging the ticketing system of a Donald Trump rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The overwhelming success of these actions may come as a surprise. But look closer at the past behaviours of K-pop fans online, and they’ve a long track record of effective campaigning. Accounts often unite to espouse the virtues of their favourite stars, tweeting video after video in a bid to convert others to their cause, or to elevate artists in the charts. In a time of great social shift, K-pop fans have just copied and pasted these tactics. They’re just as successful too, echoing a famous Bruce Lee quote that has become a rallying cry for ongoing movements around the world: “Be water.” Just as protesters in Belarus and Hong Kong are “formless, shapeless, like water” in their defiance to anti-democracy crackdowns, K-pop fans are largely the same. They are faceless, yet forceful; they unite around common causes without one clear leader; trickles turn to floods in just a single click.

To label K-pop fans as younger thus more progressive is too reductive a formula. It feels less ideological, and more a case of just doing the right thing – especially when the collective hive is as enthusiastic in defending the personal as it is fighting the political. When Marvel star Chris Evans accidentally leaked a photo of his private parts for all the world to say, K-pop fans once again battered Twitter with fancams to rescue the actor’s indignity. Many eyes still fell upon a celebrity dick pic, but it was difficult to see through the legion videos of BTS in concert.

While K-pop supergroups have donated to the BLM movement, the artists themselves are famously apolitical. Fans aren't progressive just because their heroes say so. Another message, however, is adopted, one which seems to genuinely feed into the very ideals K-pop fans strive to live by, no matter how manufactured or commercialised the source of these words. From American bedrooms to dive bars in Bangkok, the words are cutting through, and the ideas live on. To quote a rough translation of 'My Best Friend', another hit by Girls Generation: "Even if your worry may seem trivial, don’t hold it in but share it with each other. Promise me one more time: when you laugh, I’m happy too. When you’re sad, my eyes tear up."

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts