"I remember writing in this journal that I would capture father later — I meant to do a brilliant character sketch. Capture father! Why, I don’t know anything about anyone!” — Cassandra Mortmain in I Capture the Castle, by Dodie Smith

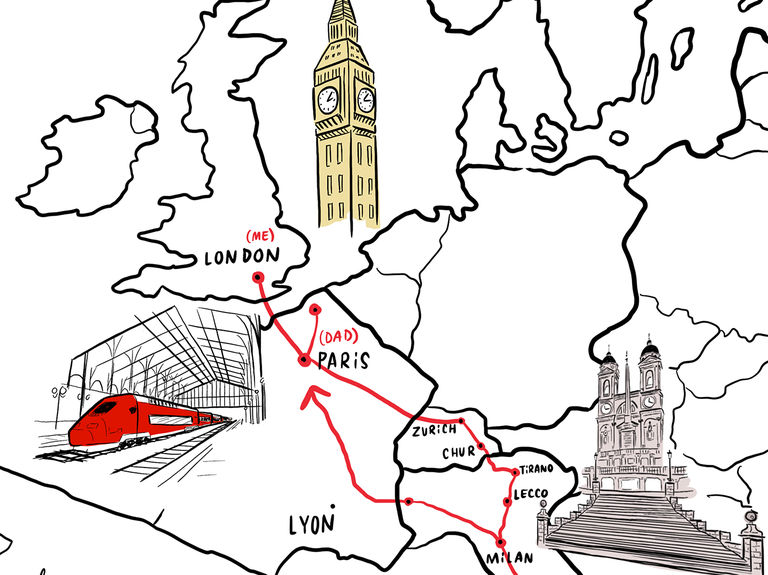

Prologue train: London St Pancras Intl to Paris Gare du Nord, 2h 24m

On the Eurostar from London to Paris on a morning in late September, as I listen to three small children on the next table enjoying three different AI-generated nursery-rhyme cartoons on three different iPads, their parents seemingly having forgotten to pack even one set of headphones, I start to wonder what I was thinking. I am on my way to meet my dad, who lives in France, to begin a train trip across Europe that I have proposed and he, with almost imperceptible enthusiasm, has agreed to come with me on. “Train travel is a major travel trend right now because the planet is on fire!” I had told him, knowing how much he, a retiree in his seventies, likes to be on top of these things. He loves trains! I thought, equally confident that it was the kind of thing he, a man, was definitely into.

Maybe there were other reasons for asking him too, to do with his age, and my age, and a rising sense of panic. But, anyway, he had said yes, I’d arranged first-class Interrail passes and — after a series of exasperated FaceTime calls over several weeks, as we struggled to make sense of the byzantine Interrail Rail Planner app and website — we have a plan. We are off to Rome, where my parents met and married 50 years ago (just to dry up any misty eyes, they’ve been divorced for half that time), and we are taking the scenic route: travelling from France to Switzerland and then through the Alps to Italy. And, though I haven’t actually told him this part of the plan explicitly, we are going to talk.

It’s something that, in the general run of things, my father and I don’t do much. We see each other maybe two or three times a year, and we speak on the phone once a month at a push, so this will be the longest time we’ve spent in just each other’s company for — I do a quick calculation — our entire lives. Now that I’m older (43) and a parent myself (of two girls), and time has started to concertina in that strange way it does, I find this mildly horrifying. Are my children, whom I’m currently loving and cajoling and battling and soothing and coaxing into being, destined to become people I exchange sporadic small talk with every now and again? When and how will that uncoupling occur? Can I resist it? Reverse it? Is it undignified to even try? And there’s another question that lurks for me about my own dad: has he even noticed?

This isn’t my first attempt to King Canute the situation. During the mania of lockdown, with all those statistical reminders of mortality, I’d resolved to ask both of my parents about themselves in a semi-structured way while I — not to put too fine a point on it — still could. Or maybe it’s just hitting middle age that draws your attention, acutely, to the fact that human relationships are finite and that if there are things you still want to know from your parents, and they can still tell you, you shouldn’t hang around.

My mum, to her credit, sang like a canary. Over several hours of phone calls, she told me about growing up in California with a bipolar mother, escaping to New York in her twenties, seeing Warhol at Max’s Kansas City, freaking out on mescaline at a transvestite party, emergency-hemming Peggy Guggenheim’s fur coat… The good stuff, basically. With my dad I had less success. Too shy to ask him directly, I proposed he give me online Italian conversation classes, thinking he might tell me things in passing. We lasted four sessions and talked almost exclusively about vaccines (i vaccini) and spaghetti carbonara. Clearly, I needed a more drastic approach.

The night before I left for Paris, my seven-year-old daughter, currently also facing down some of life’s bigger questions, asked me: “Could you die on this holiday?” It’s very unlikely, I told her (never say never!). “Could Grandpa die?” she asked. Also pretty unlikely, I said, though inside I was thinking: He’d better not.

Train 1: Paris Gare de Lyon to Zürich HB, 4h 4m

While I’ve been travelling from London, my dad has been making his way to Paris from Dieppe in Normandy. After I’ve spotted him at the Gare du Nord — braces on his trousers, wheelie suitcase in hand, eyes bulging with the disgruntled resting face typical of our family (ask any of my cousins) — it takes us approximately three minutes to regress to a comfortingly familiar dynamic of shouty (him) and surly (me). I tell him I’m off to find the toilet. “Why didn’t you go on the train?” he says, instantly apoplectic that I haven’t made sufficient use of the free onboard facilities, given that the Gare du Nord will charge me a euro. “I went six times!” he declares. Still, though you wouldn’t be able to tell from my disgruntled resting face, it’s good to see him.

After a small miscommunication over which escalator to meet at after my one-euro-toilet-trip (“I told you to turn right!”), we leave the Gare du Nord and make our way southeast across Paris by bus to the Gare de Lyon, above which, as we arrive, the national aerobatic display teams of Britain and France, the Red Arrows and the Patrouille de France, have thought to organise a noisy, red-white-and-blue-plumed fly-by. (It turns out it’s not for us, but for another short-tempered septuagenarian who happens to be gracing the city with his presence: King Charles III. I didn’t even know he was in town, but my dad, as a token Englishman, has already been interviewed for his local paper about it; he told them he was ideologically indifferent but hoped it didn’t cause unnecessary traffic.)

There follows a semi-humiliating traipse through the Gare de Lyon’s iconic Le Train Bleu restaurant, trundling our suitcases between tables and over diners’ feet — my dad having strong-armed the bellhop to take us round so I can see the fancy ceilings — before we head to our first train. It’s a double-decker, and we find our seats, which are on the lower level and side by side. Not the perfect configuration from which to interrogate him but, as the houses get pointier and more chalet-ish and the light fades, I give it a go.

It turns out four hours of hoarsely whispering questions at someone so as not to disturb the other passengers takes it out of you, as, I’m sure, does answering them (“Speak up! I can’t hear a word you’re saying!”), so we arrive in Zürich station somewhat drained. I have, however, covered a little ground. No one in my family has ever fully understood my dad’s job. My mum, my sister and I have a long-held suspicion that the apparent boringness of his line of work — data management of some kind — combined with his natural ability with languages (he speaks six) and a general air of secrecy and shiftiness, would have made him an excellent spy. Perhaps, it seems, he really was just a generic 1980s businessman who travelled a lot and knew a bit of Russian, but anyway he’s caught my drift and he’s not breaking. (“Are you expecting me to confess to something?”) All I’m saying is, if MI6 didn’t recruit him, they missed a trick.

In the evening, at a touristy, old-timey restaurant, we order a dinner of Swiss-seeming things, including venison and spätzle and rösti, all covered in gloopy brown sauce and washed down with beer. Then, in a carbohydrate-induced fug, we walk to the hotel and to our respective rooms to look at our phones in peace. One day down.

Train 2: Zürich HB to Chur, 1h 14m

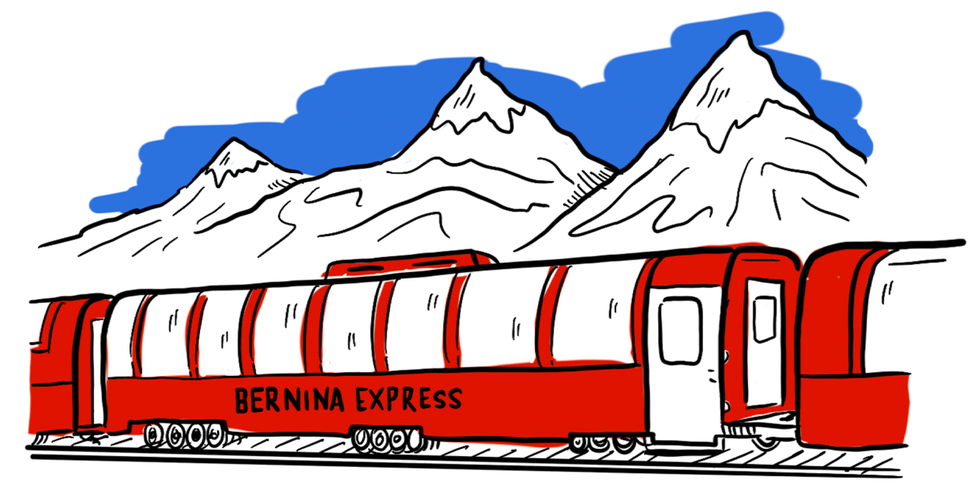

With Dad’s pockets full of the ham sandwiches he has assembled at the breakfast buffet, we check out of the hotel to kill the two hours we have in Zürich before catching the train to Chur, the starting point of the Bernina Express, a celebrated scenic railway that winds its way up, over and through the Alps. What will we do with our time before then? Take in the historic old town, where the Dada movement was born? Admire the views from Grossmünster, the imposing church at the centre of Switzerland’s Protestant Reformation? Stroll past the fancy boutiques and watch shops of the Bahnhofstrasse? But no. My dad has brought with him an old Swiss five-franc piece from 1874 he found in his attic and reckons he can flog for at least 300 current ones. In fact, he’s identified a nearby coin shop on Google, so off we go.

Ten minutes later, we’ve been into the shop and are back out on the street, the Very Swiss Man behind the counter having said, sadly, that if only it were an 1875 five-franc coin he’d have been happy to help, but he can’t move for 1874s (he pulls out a whole drawer of them to prove it). As a kindness, though, he can offer my dad 50 modern-day Swiss francs to take it off his hands. With a huff my dad agrees; we do have a train to catch. When the Very Swiss Man asks for his passport details, my dad suggests that instead he leave me, his first-born daughter, in the shop as collateral. The Very Swiss Man looks at the 43-year-old mother of two in palazzo pants standing near the door and smiles thinly.

The train from Zürich to Chur, which follows the coast of the pleasant, lawn-fringed Zürichsee, arrives in the mountain town just in time for us to grab a quick sandwich near the station before the Bernina Express departs. Or as my dad sees it, enough time for a full sit-down restaurant meal with a repeat of all the carbs and heavy sauces we enjoyed in Zürich only a few hours ago. I have a suspicion that his wife, the mother of my two half-brothers, who is on a constant, thankless, mission to curb his Rabelaisian tendencies, would not approve.

Train 3: Chur to Tirano, 4h 25m

Another thing about eating a big, heavy meal that you don’t really have time to digest, or even finish, before your train leaves, is that when you’re inevitably waddle-running to catch that train, you’re a bit slow. And so, despite having reserved seats on one of the famed “panoramic” carriages of the Bernina Express, which have curvy windows that bend into the ceiling so you can fully appreciate the spectacular mountain scenery you will be passing, with only a minute to spare my dad and I heave ourselves onto a random carriage with flat windows and a ceiling that’s decidedly non-transparent. It is also, unlike the panoramic carriages, which are full of honey-mooners and golden-wedding-anniversary types, completely empty.

At first, this feels like a shame. The Bernina Express is routinely described as a once-in-a-lifetime, bucket-list train journey; the 100-year-old narrow-gauge route takes in 196 bridges and 55 tunnels before descending from the mountains into Tirano in Italy, and was declared a Unesco World Heritage site in 2008. If you’re going to do it, you want to do it properly.

But do you know what you can’t do in those busy panoramic carriages? You can’t run to the left side of the train when you spot a GothiC castle teetering on a rocky precipice, and back to the right when you pass a gorge that plummets through the thin pine trees to a tiny snaking river down below. You can’t open the windows and stick your head out like a spaniel and feel that whoosh of mountain air on your face, and experience the thrill of suddenly entering a tunnel and not getting your block knocked off. Which we can, and do, as the train clatters over the arches of the vertiginous Landwasser Viaduct, or past the roiling clouds tumbling into the Morteratsch Glacier (“It’s like the hand of God coming down!” announces my dad), so that when the train stops to allow the other passengers a leg-stretch and fag-break, we feel a bit sorry for them. They don’t know what they’re missing.

In fact, so exuberant do we feel that Dad takes a while to notice that he’s sat on the banana he’d also lifted from the hotel breakfast buffet. As the train creaks up to the Bernina Pass and skirts the pale, milky waters of the Lago Bianco, which sits just beyond the 2,253-metre-high summit, I turn from the window to find him holding the offending banana behind his shoulder, Fatima Whitbread-style, ready to lob it into the pristine lake. Ever the stickler for petty bureaucracy, I draw his attention to the sign that says — in four languages, all of which he speaks — that it is forbidden to throw things out of the window. I turn back to the view only for, a few seconds later, a streak of bruised yellow to fly past my ear (“It’s brilliant! It’s what nature wants!”).

As the Bernina Express rattles gradually away from the mountains, we experience a comedown in both the literal and chemical senses. The altitude decreases and swathes of fog sweep in and obliterate much of the view. The corkscrewing in and out of mountains like a worm working through an apple has also left me feeling slightly green. But my dad, whose digestion is proving more robust, declares it “magical”. And, once the queasiness has worn off, I can see that he’s right.

Train 4: Tirano to Lecco, 1h 50m

It’s dark in Tirano, and with only a few minutes of changeover time we race for our connection. The platform indicator signs are broken, so we have only the shrug of a cigarette-smoking guard to indicate the right train: a grubby, graffiti-covered thing that will transport us to Lecco, on the shores of “stunning” Lake Como. “Stunning” is in quotes because if you choose to take that train in the dark, you have no choice but to stare at your own face reflected in the black pane of glass as you imagine what gorgeousness is probably happening on the other side. Perhaps George and Amal are waving to you from a speedboat right now. Impossible to say.

Luckily, the lack of view gives me the chance to type surreptitiously into my phone some notes about things my dad has told me earlier. About getting a job in an iron foundry in Manchester, the same one that employed his own dad as a joiner, and how they’d given him the task of testing the carbon content of the molten iron because they heard he was at Cambridge University — a somewhat unlikely turn of events for a working-class boy from Blackley — and didn’t seem to mind that he was studying not metallurgy but Swedish. He would hold a terracotta plant pot at arm’s length to catch a glob of glowing metal, while around him water hissed on impact as it fell from the leaking roof.

It also gives my dad enough time to check on some Ikea kitchen drawers he’s selling on French eBay. He’s got three to sell, he wants 30 euros, and, by the time we arrive in Lecco and stagger out into the night to find a pizza, he’s had a sniff from a potential buyer. Let’s just say we’re both pleased with our progress.

Train 5: Lecco to Milano Centrale, 0h 39m

In the daylight, Lake Como, encircled by peaks, some of them snowy, is actively quite pleasant. After breakfast we take a walk to its edge, where there’s a touristy market selling regional produce along the water, and from which, despite having just finished breakfast, we cadge and eat some bright-green Sicilian biscuits. It’s drizzling lightly but not unpleasantly, and we walk out to look at the golden statue of Saint Nicholas, patron saint of Lecco and of weary travellers, who is pronged on a pole on the edge of the lake and today has a black cormorant perched on his bishop’s mitre. We pick up some conkers and throw them — respectfully — in his direction, before heading to catch our next train, to Milan. The thought of schlepping through a big, brash city feels unappealing after all this alpine loveliness, plus a more worrying issue awaits us: it’s Fashion Week.

Train 6: Milano Centrale to Roma Termini, 3h 10m

Perhaps Milan on a quiet day, if it ever has one, is lovely. Perhaps cramming yourself onto a busy train from Lecco and then spending most of your few hours in the city lost in the subterranean passages of Milano Centrale searching for the left-luggage counter, then deciding instead to wheel your wheelie bags around in the rain, is not the best way to do it justice. Maybe the Duomo di Milano is a more moving experience when Korean influencers aren’t draping themselves across the chancel aisles, and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II is more elegant when it’s not steaming with dripping-wet tourists huddling for shelter. Or maybe we were just train people now, and the outside world was starting to feel… a bit much. It was with some relief that we finally wheeled our wheelie bags onto the train to Rome.

I know you shouldn’t pick favourites, but — Jesu Christi! — Rome is good. Even the train ride is a blessed relief: speeding past the distant blue Tuscan hills, through fields of sunflowers with their heads turned away; also, because this is the late-capitalist 21st century, past car parks and dilapidated farm buildings and goods yards and pylons, pylons, pylons. We enter a kind of hypnotic state. There’s nothing we need except this squishy seat, this window, this (completely free) toilet and the occasional dehydrated salty snack. We even have some new train friends on the next table, or at least my dad does — a couple of priests and a genial older Italian man heading to Rome for the weekend with his wife, who asks my dad more questions than I’ve managed.How many children does he have? (“Quattro”apparently, which, to my relief, matches my own calculations.) Which is better, English coffee or Italian coffee? (“Che domanda!” says my dad.)

Rome is still warm, but not muggy like Milan and, at the alarmingly fancy hotel we’re staying in, which has kindly furnished each of us with a bottle of prosecco and bon-bons in crystal bowls, we lean across our neighbouring balconies to clink glasses as we look out over the undulating, pinky-beige city. Before dinner at the hotel, we take a passeggiata to the nearby Spanish Steps, past the building that once housed the English school at which my parents met and taught in the early 1970s, and the bars they used to go to, and the hotel where my godfather, one of my dad’s oldest friends, who died two years ago, used to stay. “I wish I could send him a picture,” says Dad.

At the bottom of the steps, in front of the scrubbed-up Bernini fountain, the Banda dell’Esercito Italiano, the Italian Army Music Band, in white jackets and tall pom-pom hats, are putting on a rousing performance of show tunes, and this time King Charles is nowhere in sight. Maybe this one really is for us.

Train 7: Roma Tiburtina to Torino Porta Susa, 10h 46m

When we were small, ungrateful children, my sister and I spent several holidays in Italy with our parents being dragged around churches, the vaulted ceilings no doubt filled by a constant stream of our griping and moaning. Now, with almost a full day in Rome before our sleeper train to Turin, being dragged around churches by my dad is exactly what I’m after.

First, a quick trot through Piazza Barberini and the Trevi Fountain (as I throw in my pennies: Please let this trip not be a disaster!); then the Basilica dei Santi XII Apostoli, where a congregation from the Ivory Coast is singing and swaying; on to Piazza Venezia, and the Campidoglio, where my parents got married (“cinquant’anni fa!” my dad tells the mystified security guard); past the Forum and through the Ghetto for an obligatory stop for carciofi alla giudia, plus another new friend for my dad: a jovial local man at the next table. They gabble on while I, my lockdown Duolingo Italian letting me down, plough silently through my artichoke.

After lunch we cross the river to Trastevere, where my parents had a flat, and take in Bernini’s saucy statue of Blessed Ludovica Albertoni in San Francesco a Ripa, the Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere, then across Ponte Sisto to the Palazzo Spada, Basilica di Sant’Andrea della Valle, Chiesa di Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, Sant’Agnese in Agone. Then past Palazzo Madama, where a fleet of black cars is blocking the road: yesterday, the former Italian president Giorgio Napolitano died, at 98, and his body is arriving to be laid in state. And, at last, an ice cream.

It’s been tiring, but in a wholesome, bodily way, and we’re bound to sleep like putti on the overnight train. Just to be sure, we neck our second complimentary bottle of prosecco in the hotel lobby before taking the bus to Roma Tiburtina, a suburban station that is enormous, ghostly and, apparently, entirely unstaffed. When our train arrives just before midnight, it feels like a mirage. Though our connecting cabins aren’t the cleanest, there’s a bed and a basin and a packet of bits and bobs, including little plastic slipper-bags to put your feet into if you need to shuffle to the toilet. I put my earplugs in and adopt the foetal position, because there’s nothing like the gently joggling motion of a sleeper train to make you feel like you’re back in the womb. Just in case this trip weren’t regressive enough.

Train 8: Torino Porta Susa to Paris Gare de Lyon, 6h 46m

When I can hear my dad moving about in his cabin the next morning, I open the connecting door. Immediately he asks, “Is there something on my head?” And yes, Dad, there is: a gash across the top of his skull, now turning sticky and black, which he apparently acquired while getting out of bed and headbutting the edge of the folded-away upper bunk. I dab at it with a large wet wipe from the packet of bits and bobs. When I’m finished, the wet wipe has taken on a pleasing resemblance to the Turin Shroud, which happens to be awaiting us in our destination city, our final Italian stop before taking our last train north to Paris.

As it turns out, the Turin Wet Wipe is as close as we are going to get to sightseeing today. In Torino Porta Susa station, during another failed attempt to find a left-luggage facility, we are informed that the hand of God has indeed descended, or perhaps the Trevi Fountain felt short-changed: there has been a landslide in southeastern France and our train to Paris has been cancelled. Oh, and the landslide happened a month ago, meaning our train was also cancelled A MONTH AGO. But the Interrail Rail Planner app seems blissfully unaware of this event, and so, as a result, are we, though the Italian station staff appear intent on blaming our lack of information on their French counterparts. More pressingly though: we have no way home.

Train 8: Torino Porta Susa to Torino Porta Nuova, 0h 10m

We take a local train one stop to Turin’s main station, Porta Nuova, partly to gather ourselves, and partly to work out if this hasn’t all been some kind of amusing misunderstanding. At Porta Nuova though, our fate is confirmed. “Yes, a landslide,” say the Trenitalia employees, shaking their heads. “We can’t believe the French didn’t tell you.” Forlornly, we wheel our wheelie suitcases to a café across the street from the station and consider alternative routes. By which, I’m ashamed to say, I mean that we jettison all thoughts of carbon footprints and father-daughter bonding time and frantically look up some kind of flight — any flight — that might get us somewhere vaguely useful (Birmingham? Belfast?) and bring the trip to a conclusive, decisive end.

But wait! No. We are not going to fly. (And not just because there are no flights going anywhere convenient for another two days.) For we are train people now! Train is what we know! Train is what we do! WE ARE TRAIN. I steel myself and study the Interrail Rail Planner app with renewed focus.

There’s nothing like looking at a map of Europe to make you realise that things are further apart than they seem when you’re cruising at altitude over a blanket of cloud. As quickly as I can, I plot potential overland routes to Britain that have a worrying resemblance to the opening credits of Dad’s Army. Ah, look! If we ditch any plans to see anything of Turin beyond the café in which we are currently sitting, we can head straight back to the station, catch a train to Milan, return back through the Alps to Zürich, pretty much entirely the way we have come, and be in Paris before midnight. We down our coffees and start wheeling.

Train 9: Torino Porta Nuova to Milano Centrale, 1h 2m + Train 10: Milano Centrale to Zürich HB, 3h 17m + Train 11: Zürich HB to Paris Gare de Lyon, 4h 21m

Including the sleeper, we spend nearly 20 of Day Five’s 24 hours on trains. We enter a fugue state. It is now hard to imagine a life outside the train. A life where our legs do more than totter to the toilet and back. A life that isn’t sustained solely by the packets of salty dehydrated snack foods we have mineswept from the vacated sleeper cabins in Turin. A life where more is expected of us than to look out of the window and take in the looming mountains, the narrow waterfalls, the hydro-electric plants, the spindly motorway overpasses. A life where the comings and goings of the outside world mean something, and there are scandals of interest beyond those happening on the train (which, on the Zürich to Paris leg, involve a young English woman who gets shirty with the Swiss ticket inspector; in Paris, she is met off the train by a squad of armed police officers).

I’ve given up questioning my dad — it has exhausted us both — and he, after a single, valiant attempt (“Why do you drink so much water?”) has given up questioning me. We are now worn down enough to sit in silence, or to look at our phones or, in my case, to blurt out any inane thing that pops into my head, regardless of whether or not I think he’ll find it impressive or amusing or interesting (and which, for the most part, from what I can tell from the lack of modification to his disgruntled resting face, he doesn’t). I even, finally, get out my book (“Oh thank god!” he says).

And it’s great. It’s exactly the kind of low-stakes, largely non-verbal interaction we used to have, like watching Jeremy Beadle-era You’ve Been Framed! on the sofa, when he’d laugh so hard my sister and I would eye him nervously in case he was having a heart attack; or accompanying him on weekend mornings as he scavenged weird brass fittings from the markets on Kingsland Road or Brick Lane. We didn’t chat. Ugh! We knocked about. We bobbed along. And maybe it has taken 35 hours of talking on trains to get to back there, back to not talking, but it’s nice.

Epilogue train: Paris Gare du Nord to London St Pancras Intl, 2h 29m

In Paris, Dad and I go our separate ways. We exchange the briefest of pleasantries. He thanks me for inviting him. I thank him for coming. There are no emotional outpourings. No doubt we won’t speak again for weeks (and, sure enough, we don’t). Then, braces on, eyes bulging, he wheels his wheelie bag to Gare Saint-Lazare, to get his trains back to Dieppe. I wheel my wheelie bag to the Gare du Nord, to get my train to London.

On the Eurostar, I return to my book, I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith. It’s a children’s book really, or more specifically a book for young girls on the cusp of adulthood, which I’m reading again to check it’s not too racy for my 10-year-old daughter. Written in 1948, in a whimsical, la-di-dah way, it’s about 17-year-old Cassandra Mortmain, who lives in a rundown castle with her brother, sister, stepmother and father, a once-celebrated author who is suffering from writer’s block. Cassandra decides the only way to help her father write again — and maybe to understand him a little bit — is to lock him in a tower. He’s furious. “Oh father, it’s an experiment — give it a chance,” Cassandra implores him. “You little lunatic,” he rages. It is all, if I’m honest, a bit on the nose.

Eventually though, Cassandra’s father starts writing again. Imprisoning him turns out to have been a good call. Could I say the same? Certainly, I knew more things about my father than I used to. That he shared a room in college with a member of the Angry Brigade; that he taught English on a naval base in Puglia, where, in the evenings, he and the sailors would stroll about arm in arm; that he was involved with various ahead-of-their-time-sounding business ventures (one of which appears to have been a proto-Amazon — ah, what could have been); that he got 25 euros for the Ikea drawers he was selling on French eBay.

Could I tell you what he felt about any of it? Gracious no! I can’t work miracles. Though he did seem quite pleased about the drawers. But I can say with certainty that, for a few days, I took him prisoner, and he was decent about it. And then, on a street corner in Paris, I let him go. ○

Miranda Collinge is the Deputy Editor of Esquire, overseeing editorial commissioning for the brand. With a background in arts and entertainment journalism, she also writes widely herself, on topics ranging from Instagram fish to psychedelic supper clubs, and has written numerous cover profiles for the magazine including Cillian Murphy, Rami Malek and Tom Hardy.