If any year is going to have you reaching for the philosophy books, it’s this one. And if it’s resilience you’re after, you could do a lot worse than the Stoics.

I first dug them out back in January 2020, when the world had gone only part of the way to hell in a handcart. As it rolled into spring and the virus spiked, so did sales of two of Stoicism’s core titles, Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic and Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, which were proving as hard to track down as kettle bells and 00' flour.

When the shit hits the fan — especially one turned up to the maximum speed setting — people tend to return to this particular philosophy-of-life-come-ancient-self-improvement-programme, whose 500-year heyday in Greece and then Rome ended a dizzying 17 centuries ago.

One explanation for its prescience might be how it drums the distinction between what you can control (your voluntary thoughts) and what you can’t (everything else). Useful to be reminded of when you’re under house arrest. The Stoics, I should point out in advance, like to shoot from the hip. And much of what they were saying 2,000 years ago is only now being incorporated into what we might call 'modern' psychology.

“That all is as thinking makes it so — and you control your thinking. So remove your judgements whenever you wish and there is calm,” writes Marcus Aurelius in the Meditations. Slowly, this helped me deal with joggers.

It’s also in this Stoic principle that modern-day cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) took its inspiration. And it turns out they had cupboards full of this stuff.

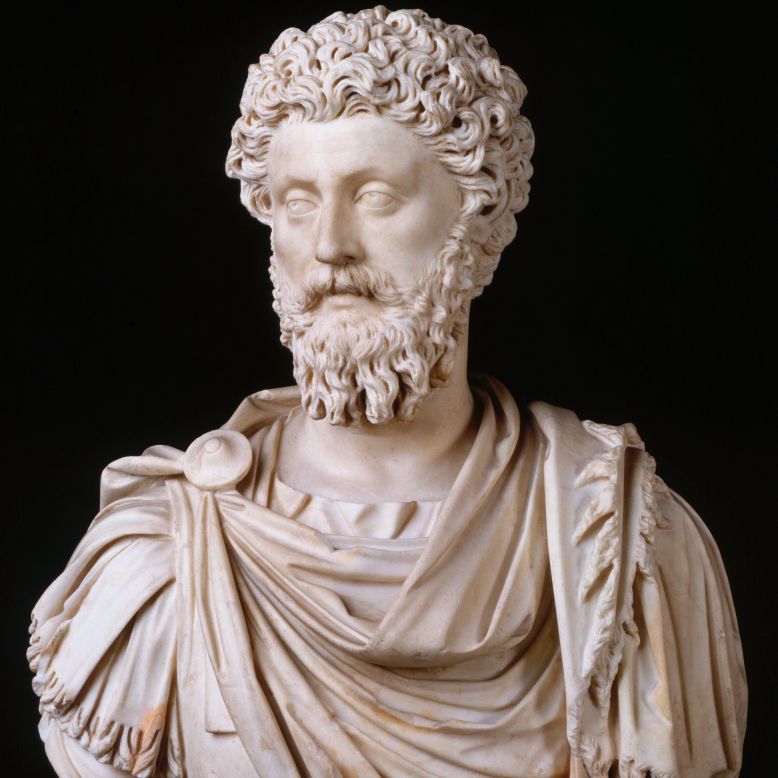

Marcus, who was born 1900 years ago on 26 April 121 AD, had been trained in these techniques since he was about 12 and by the time he wrote his Meditations, he was a black belt, metaphorically speaking; naturally such status signifiers are not part of the Stoic lexicon.

What’s remarkable about the Meditations is that we get to read the private self-improvement journal of a Roman emperor; the most powerful human being in the world in his time, and possibly any other; the fifth and last of Rome’s so-called “good emperors”.

“‘It is my bad luck that this has happened to me’. No, you should rather say: ‘It is my good luck that although this has happened to me, I can bear it without pain, neither crushed by the present or fearful of the future.’”

Written when Marcus was in his forties, mostly while fighting wars in modern-day Austria, these are not diaries and there are almost no mentions of the historical events he was actively shaping by day.

Instead, they are admonishments with himself to be wiser, kinder, more focused, less irritable; not intended for anyone to see, let alone be published. Oh, to have a leader who was trying this damn hard.

Their intimacy makes eavesdropping on them across the centuries even more atmospheric. Although it’s frequently hard not to hear them in the whispered voice of Richard Harris, who played Marcus in Gladiator.

Many entries start with “Remember”, “Keep in Mind” and “Do not forget”, while some are written in dialogue with himself, including one on how to resist a lie-in:

“At break of day when you are reluctant to get up, have this thought ready to mind: ‘I am getting up for a man’s work…. Or was I created to wrap myself in blankets and keep warm? “But this is pleasant…’”

It’s fair to assume that if Marcus were alive today he would not have spent the first few weeks of lockdown watching The Last Dance. Occasionally he gets impatient with his own prevarication: “No more roundabout discussion of what makes a good man. Be one!”

To read them in one go is not how they were intended and makes for an intense experience; the psychological equivalent of being hosed down by a team of heavily armed counsellors.

On the plus side, this can feel strangely refreshing. And it puts it about as far away from the Pollyannaism of modern self-help as it’s possible to get.

There are constant reminders that his – and our – individual problems don’t amount to a hill of beans. “The whole earth is a mere point in space: what a minute cranny within this is your own habitation.” You have to hope he was on better form at parties.

Several times he writes about how once cocky figures like Alexander the Great are now just dust. “All things fade and quickly turn to myth: quickly too utter oblivion drowns them… So in all this it must be folly for anyone to be puffed with ambition, racked in struggle or indignant in his lot.” It was Marcus’s way of saying ‘don’t sweat the small stuff’.

Nowhere does he more succinctly describe the impermanence of human life than with the line: “Yesterday sperm: tomorrow a mummy or ashes.” Ouch. If you found these thoughts in your partner’s study neatly typed out in a big pile of A4, you might feel a bit like Shelley Duval in The Shining and want to check the location of the family axe.

This is to look at it through slovenly modern eyes. Marcus wrote most of it during the Antonine plague that killed upwards of 8 million people and lasted over a decade. A plague that took his family name, that his own soldiers likely brought back from war and that may ultimately have killed Marcus himself. I know what you’re thinking, “but did he have to homeschool with a flaky broadband connection?”

He did face foreign wars, civil wars, floods and famines, was constantly ill and, astonishingly, eight of his children died before him. That he managed to carry on at all is a pretty strong validation for how teak tough a lifetime of Stoic training had left him. From all historical accounts, it seems he actually lived up to these standards too.

You’d be forgiven for wondering if all this morbidity might make you want to stay in bed rather than jump out of it, but used correctly the effect was motivational.

Stoics liked to ‘memento mori’ – remember death – believing that only by facing down its reality from time to time can we live a more purposeful and grateful life in the present moment. Another trick that we are only now starting to catch up with.

“No, you do not have thousands of years to live. Urgency is on you,” is a typical reminder to himself not to squander this hour, this day, this life.

At 58, Marcus faced down his own death, even refusing food to quicken his decline.

As his friends despaired, Marcus reminded them that this was the natural order, and we should leave it gladly “as an olive might fall when ripe”. Stoicism itself soon hit the skids too, though it's enjoying something of a 21st renaissance, with Marcus's Meditations at its heart.

It’s either poignant or ironic that Marcus repeatedly writes about the emptiness of fame and yet he is remembered as a philosopher two millennia later.

I’m guessing he’d be even less keen to know his private journal has since become Bill Clinton’s favourite book and is currently doing the rounds amongst the executives of Silicon Valley. But these are things not even emperors can control.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts