What can there be left to say about Beatlemania? Plenty. The Beatles’ arrival is one of the most consequential events of the Western twentieth century. You might as well ask: what’s left to say about World War II? There will always be stories we haven’t heard, ways that the event has reverberated into the present day, and ways it changed the lives of people who weren’t even born to see it. As happened with WWII, the number of people who were there to witness it is beginning to shrink, so we’d better cherish those primary testimonies while we can still get them.

Which is why 1964: Eyes of the Storm, the new book of recently unearthed photos taken by Paul McCartney during the Beatles’ first American visit in February 1964, deserves to be received with the same gravity you’d pay any primary source for any great historical event. That trip saw their world-changing—and I do not use the term hyperbolically—appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, as well as their first American concerts in Washington D.C. and at Carnegie Hall. The Harvard historian Jill Lepore, who wrote the volume’s introduction, seems to understand the visit’s gravity. As she documents the day-to-day happenings on this trip, she places them among the world events taking place at the same time. Just in the months leading up to the Beatles’ breakthrough in America, when the UK was already succumbing, and reeling from the Profumo affair, Nelson Mandela was put on trial in South Africa, while the day that saw the release of their second album With the Beatles, coincided with JFK’s assassination in Dallas. As a historian, Lepore understands that Beatlemania carries enough weight to be listed beside these events.

It’s important to note that we’re talking about Beatlemania—not the group’s musical legacy, nor the changes they set off to music, to the way men could look, and to the very acceptance of a life lived as a duty, without the transformative camaraderie they embodied. But what had to happen before any of that was possible, namely, was their initial explosion in the collective consciousness of the West. Any pop event that takes over the imagination of a huge swath of the population presents itself as both an affirmation and a negation. That was as true of Elvis before the Beatles as it would later be true of punk and, for a brief moment, Nirvana. These events may start by offering previously unimagined possibilities, or by rejecting the available choices, but they all will finally do both. That’s why the Sex Pistols gleefully proclaiming “No future for you!” points a way forward, and why there is a rejection of anything less than utopia in “Eight Days a Week,” with the Beatles saying that the joy and love they were singing about was so big that time itself would have to expand to encompass it.

Neither in its photos nor in McCartney’s accompanying commentary is Eyes of the Storm a complaint about the price of fame. “You might think,” McCartney writes, “that we felt like animals in a cage. I can only speak for myself, but I did not feel that way. This was something we had always wanted, so when it actually happened, when the mounted policemen held back the crowds outside the Plaza, I felt like we were the stars at the centre of a very exciting film. And the good thing was there was never any malice. The people running after us just wanted to see us, just wanted to say hi, just wanted to touch us.”

McCartney’s written interstices often sound as if they stem from the same affability that has long defined his public persona. But they don’t feel like someone doing a PR job. The years since the trip seem to have clarified what he felt, and solidified his impulse to generosity. He talks about the friendly eyes watching him and his groupmates, but he’s not naïve. In one passage, he writes about how a car he was riding in pulled up next to a motorcycle cop, giving him a view of the holstered gun on the officer’s belt—a sight that shocked him, three months after JFK’s assassination. He also writes about the openness, the feeling of possibility he felt, tied to both the working-class people he saw, who reminded him of people he knew back home in Liverpool, and the ebullience of the R&B he and the rest of the group had long listened to. Nowhere is he more moving than in this passage:

“I’m reminded of an America that I know still exists, somewhere. I remember all those stories, some of them real, others imagined, from looking out of the train window, seeing American freight trains, American railway yards . . . It’s the majesty of all those beautiful old blues songs, and I begin to wonder how all those people hitched rides across the country in the old days.”

He doesn’t think or suspect that America still exists—he knows. In those lines, the Beatles’ journey merges with those cross-country rides, and with their simultaneous mixture of discovery and uncertainty.

That sense of possibility the Beatles passed on to the people who heard them and responded by saying “Yes!”, that sudden feeling that love and work and everyday life itself could be buoyed and sustained by the good feeling of friendship—all this becomes even more remarkable when you think that by the time it happened, it was being stirred up by young men living in an increasingly restricted world.

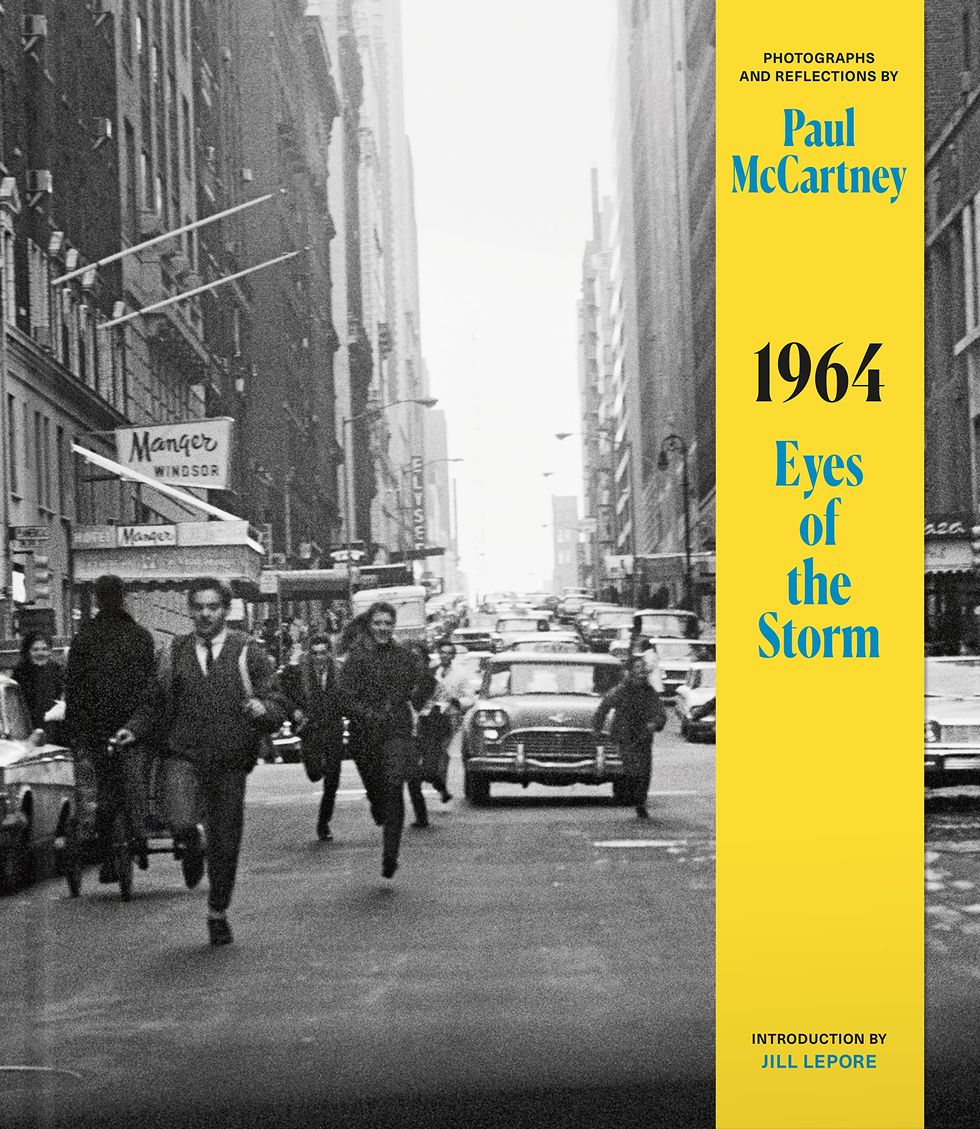

Eyes of the Storm catches the Beatles not just in the American cities they visited on their first trip—New York, D.C., and Miami—but in the European cities that preceded it, like their home base of Liverpool, London (where they played before the Queen at the Royal Variety Performance), and Paris, where they shared a bill with Trini Lopez and Sylvie Vartan. (Good Lord, how?) What we see is what we’ve come to expect from years of stories about the isolation forced on them during tours, (and the itinerary that Wilfred Brambell, as McCartney’s grandfather in A Hard Day’s Night, characterized as “a train and a room and a car and a room and a room and a room”). Except that it doesn’t look awful. Exhausting, yes. Maybe even boring. You get the sense not of energy being dissipated, but of an open curiosity. What’s unique about these photographs of the great-coated New York policemen, both on foot and on horseback, encircling the Beatles or the solitary press photographers mixed in among the cops, or the fans running down the street or pushing at the barricades, is that they lack what all the other photos we’ve seen of this event have given us, namely the composed eye that professional photographers are able to bring even to shots taken on the fly.

That doesn’t mean the photos McCartney took, forgotten by him and undeveloped for years, are merely the work of an amateur photographer fooling around with his Pentax. The adulation and protection and scrutiny coming from the subjects of these photos are being seen by the person who is the object of it. It’s a weird stroke of luck that the undeveloped roles McCartney took during those months sat in a drawer, undeveloped until an assistant discovered them. There’s a slight uncertainty to the compositions—a sense that, even stopped in time, the photos are in the process of composing themselves, a process that won’t be finished until the photographer has achieved what McCartney has achieved with Eyes of the Storm, the ability to comprehend the experience, even if he will never fully resolve his feelings about it. No matter how friendly he found the faces looking at him, this is the work of an idol in the making determined to stay a subject instead of becoming an object.

What stands out here is both the generous curiosity the photos show towards the unknown and the affection they show towards the known. McCartney didn’t have to go through what most photographers hoping to capture candid and intimate shots must do: he didn’t have to gain his subjects’ trust. There’s an effortless familiarity to the shots of the boys reading the newspaper in their Plaza suite or looking up in the midst of a conversation halfway across the Atlantic, no guardedness when their eyes meet their mate’s camera.

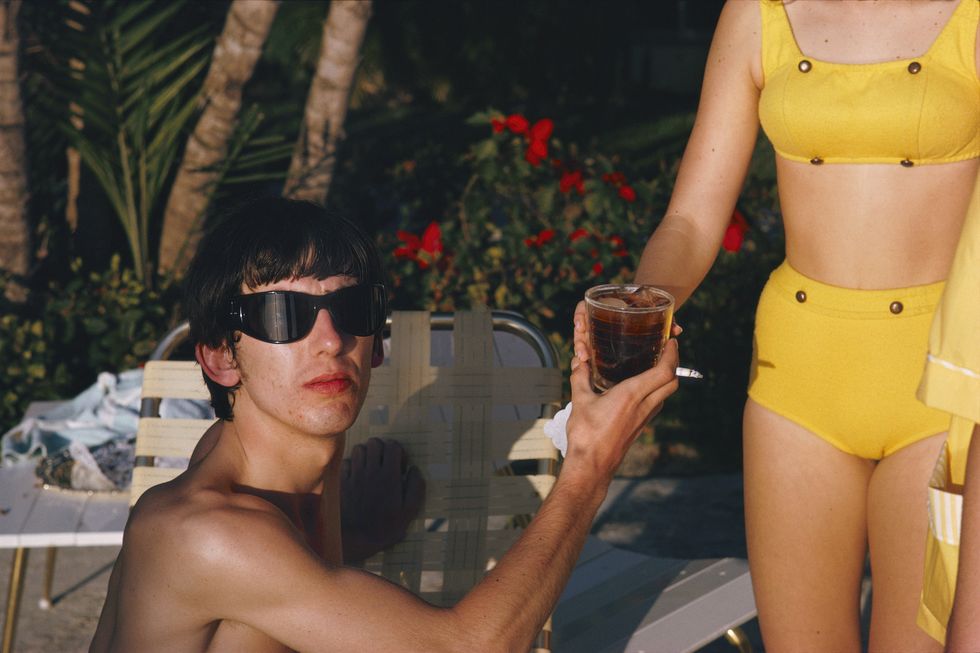

Out of all the photos, the one that immediately stands out to me is a color shot taken during the group’s Miami respite, showing a very young George Harrison, shirtless and in huge dark sunglasses, sitting poolside and accepting a proffered cocktail from a young woman in a yellow bikini. He looks into the camera like a young pasha, as if the ease and comfort he is enjoying were his from birth. It’s like a hip version of one of Slim Aarons’s shots of the idle rich. From that same vacation, there’s another shot, heartbreaking and endearing, of their manager Brian Epstein. (There is a real case to be made that the Beatles would never have made it out of Liverpool if it weren’t for his vision and persistence; Anthony Wall and Debbie Geller’s stunning 1998 BBC documentary, The Brian Epstein Story, makes that case—and does so much more. It’s time for the rights issues preventing its American exhibition to be cleared up so it can be widely seen.) Brian, so famously buttoned up and proper, has allowed himself the small casual pleasure of a poolside towelling jacket. And beneath it, a shirt buttoned to the very top.

For all of the generosity with which McCartney talks about America, for all the awe the group felt at being here and being accepted here, the photos show all the ways in which the Beatles, even before they arrived, had already outpaced the country. Look around the edges of A Hard Day’s Night and you’ll see signs of the drab austerity England was still facing almost twenty years after the end of World War II. There’s no equivalent for that in the America the Beatles found, still enjoying (the white middle class was, at least) the sustained prosperity that started under Eisenhower, constantly remaking itself in space-age style to be ready for the future we were all certain was coming faster than we knew.

But even in the posh locales where the Beatles found themselves—the Plaza in New York, an equally fancy hotel in Miami with the use of a private pool—the décor and styles, the looks of the people we see, seem stalled. Not drab, not shabby, but asleep. Maybe from boredom, maybe from complacency, maybe because after the shock of JFK’s murder, asleep felt like the safest place to be. The snow around the White House in McCartney’s picture, the half-pulled shades in all the windows, make it look like a place only open for business half days. We know that wasn’t true. Not with LBJ going at warp speed to pass the most liberal agenda of any president ever while he still had the sympathy and good will of the country. But in what we see when it comes to wit, style, beauty, desirability, energy, and the feral sense of living NOW!, nothing touches the Beatles. Later in 1964, A Hard Day’s Night would contain a joke from a clueless trendsetter looking for an “early clue to the new direction.” Here’s that clue, all four of them, months before the scene was even filmed.

There is an exception to this: a shot, taken in the Beatles’ Plaza Hotel suite, of Ronnie Spector. She’s sitting in an easy chair, looking over her right shoulder at McCartney’s camera, cool, composed almost to the point of arrogance, looking utterly unflappable. “All four of us loved The Ronettes,” he writes beneath the picture. Of course they did. How could a group whose music sounded like everything you ever wanted out of life resist the compact utopias of “Be My Baby” or “Walking in the Rain,” songs in which the sonic depth of Phil Spector’s production finds its match in the depth of emotion welling up from those three women? In this wonderful book, with its photos of a superpower as a sleepy giant, a country where most of the people couldn’t see the future beyond a continuation of the sameness in which they already lived, Ronnie Spector was the future. Not just because she was Black and because Black people would demand, in Langston Hughes’ phrase, that “America be America again” (or, for them, that it be America for the first time). But because what defined her music was the hunger for pleasure, for joy, for living with style (which the great Black essayist Albert Murray would call a strategy for survival) that would animate everyone who would clamour for a different America in the years coming faster than anyone could foresee.

And that was the promise the Beatles had held out. Inspired by and energised by American music, they brought forth a new version of that music, and offered a sense of community that, paradoxically, allowed people to think about the person they always wanted to be, the life they always wanted to live. The original discoverers of America took the land away from its inhabitants. The Beatles, generous explorers, did their part in giving it back to us anew.

Charles Taylor is the author of “Opening Wednesday at a Theater or Drive-In Near You: The Shadow Cinema of the American ’70s.” He lives in New York.