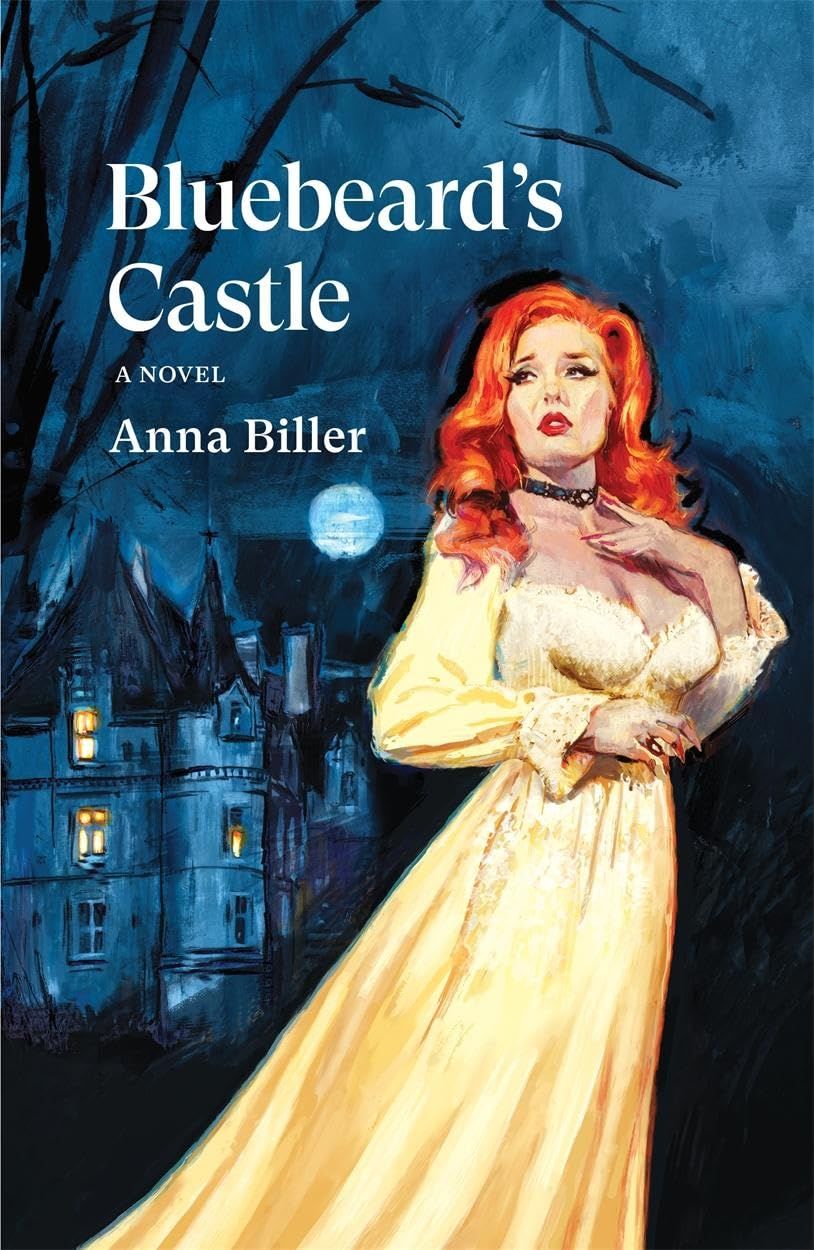

When director Anna Biller comes to mind, chances are, you think of sumptuous visuals, references to golden age Hollywood films, and intricate film production. You may remember that Biller broke through in 2016 with The Love Witch, which she wrote, produced, and directed. The film used conventions of 1960s horror films, like the lighting and aesthetics of Technicolour movies, to craft a fun and fascinating meditation on female agency and the destructive consequences of misogyny. The Love Witch received critical acclaim to become a cult favourite among horror fans and feminist film theorists alike. Now, Biller has turned her ability to weave timeless tales to the world of prose and penned her debut novel, Bluebeard's Castle.

Originally conceived as a screenplay for an upcoming film, Bluebeard's Castle may share a cover aesthetic with gothic novels from decades and even centuries past, but its reflections on the nature of abusive relationships are exceedingly timely. Biller envisioned her protagonist, Judith, as a savvy, successful, and romantic woman who embodied the experiences of the women she's known who fell prey to abusive men and didn't survive. Judith, a rabid reader and writer of gothic romances, understands the idealised tropes of damsels in distress and dangerous men with secret hearts of gold, yet that knowledge cannot save her. "I really wanted to make the point that intelligence has absolutely nothing to do with the emotional decisions that people make," Biller tells Esquire.

As she adds "novelist" to her long list of credentials, Biller hopes to join the canon of female authors who wrote novels for women and found freedom in the ability to express their ideas through fiction. Grippingly intense and emotionally resonant, Bluebeard's Castle plants the reader firmly in the mind of a woman being masterfully manipulated, stripping bare any clichés and misconceptions about domestic violence. The result is a brutally honest glimpse into the tragedy of intimate partner violence that millions of women around the world have experienced. Bluebeard's Castle draws upon generations of similar stories, from Wuthering Heights to Rebecca to modern day Harlequin novels, to paint a powerful reminder of the long history of misogynist violence. Biller spoke with Esquire about gothic tropes, gendered violence, and the stories that haunt us.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: What drew you to write a gothic novel for your first novel?

ANNA BILLER: It was originally going to be a movie. I've always been obsessed with women in peril pictures and classic Hollywood films. I was working on the screenplay for several years, and I was shopping it around all over Hollywood. I had many meetings, and it just never came together. I realized in so many ways those classic Hollywood movies I loved were all based on gothic novels and gothic romances. I had so much fun writing the book. It just seemed like this is like the form the story needs to be in.

How were you able to convey your character Judith's inner world so vibrantly?

Well, unfortunately, that was all kind of a stream of consciousness. It was scary how easy it was for me to write that. I'm well adjusted, but I feel like I have some kind of panic and hysteria in myself, and I observe it in other women. It's kind of like a certain personality type that I've either felt that way, or I've observed it in certain people I've known. So I based it on a combination of myself and women I've known. This feeling of when you're in love, and you start to feel abandoned, and you start to get desperate. I don't think it's just women. I think people who are in love can get really obsessive. It's kind of an insanity just to be in love.

I think people who read romance know what that's like, and it's why they read romances. And yet we couldn't categorise this novel under the romance category. In order to market it as romance, it has to have the happy ending. Years ago, when it was really hot, I read 50 Shades of Grey, because I was interested in why everyone was so obsessed with it. I was already working on my Bluebeard script, and I thought, "Christian Grey is a Bluebeard." He was a sadist, and he was terrifying. I think a lot of women identify with being with a bad man and not being able to break away. I only read the first one, which has kind of an ambiguous ending, but by the end of the trilogy, she ends up taming him. The fantasy that women have when they read romance is, "I'm going to tame him—the wild beast." So as long as she's able to tame him, then it's a romance, right? That was Judith's fantasy, thinking, "He'll love me the way I want him to love me, and I'm determined to get him to do it." That's why the first line of the book is, "Some men are pussycats and some are Bluebeards..."

In this book, you often talk about tropes and archetypes. Judith is like the damsel in distress, but in her lucid moments, she thinks of herself as the mad wife from Jane Eyre—the wife who was locked in the attic instead of the wife that was loved. What do you think we can learn from these tropes that Judith wasn't able to?

She was deluded by the tropes. She read too many romances, and it turned her head and she made bad decisions. She's like Madame Bovary, because her reading is actually misleading her into thinking that the world is safer than it is because the heroine always wins. I don't want this to be a big downer for the reader, but I think young women especially need to realise that sometimes men are extremely dangerous. I thought the Bluebeard story is a perfect fairy tale to explore that. I really wanted to make the point that intelligence has absolutely nothing to do with the emotional decisions that people make. It doesn't matter how much you intellectualise your feelings, because your emotions can override that. Your mind can reason anything. You can't intellectualise yourself out of being in love. She tries to do it, but she can't. She has no nourishment for her soul without him, and yet he's the worst thing for her.

That's based on real life. I knew this young woman who overdosed because she had a fight with her boyfriend, and she was so depressed that she wanted to die. Then he took her to the hospital and dumped her there. I picked her up from the hospital, and the first day, she said, "I hate him. He was going to let me die." She was really clear and lucid about everything, and realised that he was a terrible person. But then, she kept rationalising the situation to herself. Two days later, she was desperate to see him again, and she didn't get out of that situation. One of the reasons I wrote the book was because of her. Women lose their life and don't escape these situations. There's so much femicide. Isn't that what Bluebeard is—a serial killer of women? It's no less prevalent than it's ever been. Victims are so blamed, and it's happening already with my book. People have been leaving reviews, blaming Judith for not getting out of her situation.

There are many mentions of fairytales in Bluebeard's Castle. What was your favorite fairy tale when you were a kid?

Honestly, I don't really remember, because I read so many fairy tales and I like them so much. Recently I was reading this really interesting book, Why Fairy Tales Stick, by Jack Zipes. It's really explaining why fairy tales are like memes. They started as an oral tradition. Then they were written down. They keep getting regenerated and reproduced for hundreds of years in different forms, and they stick in our consciousness. I think that's why I wanted to write about Bluebeard—because I wanted to retell a fairy tale that's so embedded in the cultural consciousness. I wanted to be another storyteller telling the story in a new way, in a way that is not just my personal book, but a book that belongs to the legacy of Bluebeard.

Judith says at one point, "It's my choice to be objectified and debased. It's fun and empowering." Can you talk about your portrayal of female objectification in this novel—how it can be pleasurable for women, but also dehumanising at the same time?

Yes, there's the benign version and the evil version of objectification. When you like being objectified, what it really means is—you like being admired, and you like being loved and desired. It isn't the same thing as what objectification really means, which is to be dehumanised and reduced to a surface. The end result of objectification is that people are seen as subhuman and not worthy of even living sometimes. I feel that there's a lot of dehumanisation that goes on that people won't accept as dehumanisation, especially when it's happening to them. So within a sexual relationship, it's often really hard to know: where is the line? The line might be in the consciousness of the partner. Does the partner love me and desire me? Or does the partner actually hate me? Are they trying to dehumanise me? It has to do with getting into the mind of the other person, because it isn't really the act so much as it is the intentionality behind it.

The details about all of the clothing and fashion in the novel really added depth to the characters. What was your thought process behind writing about the fashion choices of your characters?

The characters became real characters for me when I was writing the screenplay. I do all my own set design usually, so I have huge list of props, costumes, and sketches. The scene of the masquerade party, where Judith wears that golden gown she found in the castle—that was a little nod to Rebecca, when she wears a dress that's in a painting of an ancestor of her husband, and it really triggers her husband, because the former Mrs. De Winter wore the same dress. And so Judith says in that scene, she hopes it won't be a gaffe, like that moment in Rebecca. But Judith was also thinking about the ghost in the castle and the painting of the previous lady of the castle, she's so haunted by it. I just thought it just seemed kind of natural.

Judith has a vivid fantasy life, and even when her husband is acting horribly towards her, it's part of this wildly romantic fantasy love. Romanticising traumatic experiences can be a defence mechanism as a way of processing trauma. Did you think about how people would interpret Judith's mindset as possibly romanticising abuse?

I didn't think about it, because I don't think that's what I'm doing. I think that women's experiences need to be talked about. Female artists are talking about what happens rather than what other people think should happen, or how it's virtuous to behave. Years ago, I decided I'm going to make work about what I really think about and what really happens, even if it's terrible, even if people hate it. So I'm used to thinking in this way.

Men have so much range in what they are able to discuss about their experiences. There are so many thrillers or noir films where there's a femme fatale who's evil, and he's in love with her, and everybody understands that. Nobody's blaming the man. Nobody's saying he's weak, he's stupid, he's terrible. Because everybody understands what men go through. We're so used to looking at the world through a male lens. But we don't do the same with women. We don't say, "This man is offering a woman all this love and romance, and he's doting on her, but then he shows these glimpses of evil." Instead of blaming the man for being evil or manipulative, they blame the woman. "Why was she so stupid? Why is she such a victim?"

Your work has such a feminine quality. Feminine aesthetics are having a mainstream moment right now, as young people are embracing hyper-feminine aesthetics. But there has always been and still is a backlash against those who appear very femininely—that we're frivolous or unserious. Were you worried about that critique when you published Bluebeard's Castle?

Because of that, my work has always been a little bit underground, and not necessarily thought of as serious work. But, no, I didn't occur to me when releasing my book. I thought I was getting out of that by writing a novel and trying to write it so traditionally. I tried to write it in a very classical style, even though it has modern characters. It's written how books used to be written, like novels by Daphne du Maurier or the Brontë sisters. A lot of classic literature has a femininity that is unapologetic. What's so wonderful about novels as opposed to movies is that there's a long tradition of novels written by women, for women, especially in the gothic tradition. And I thought, "I want to be part of that."

Sirena He is an editorial assistant and writer who focuses on media and culture. She is a lover of horror films and believes in the healing power of storytelling.